Proceedings, International Snow Science Workshop, Banff, 2014 1109

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

White Paper on Tourism in Japan, 2007

WHITE PAPER ON TOURISM IN JAPAN, 2007 (Summary) CONTENTS Current Status of Tourism in FY2006 Part I New Strategies for a Tourism Nation Chapter 1 Establishment of the Tourism Nation Promotion Act・・・・ 1 Chapter 2 Economic Effects of Tourism・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 4 Part II Status of Tourism and Measures in FY2006 Chapter 1 Current Status of Tourism・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・23 Chapter 2 Creating Attractive, Internationally Competitive Tourist Locations・・・・・・24 Chapter 3 Strengthening the International Competitiveness of the Tourism Industry and Developing Human Resources to Contribute to the Promotion of Tourism・・・28 Chapter 4 Promoting International Tourism・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・29 Chapter 5 Improving the Environment to Encourage Tourist Travel・・・・・・・・・・30 Measures for Tourism in FY2007 Chapter 1 Creating Attractive, Internationally Competitive Tourist Locations・・・・・・・32 Chapter 2 Strengthening the International Competitiveness of the Tourism Industry and Developing Human Resources to Contribute to the Promotion of Tourism・・・・33 Chapter 3 Promoting International Tourism・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・33 Chapter 4 Improving the Environment to Encourage Tourist Travel・・・・・・・・・・・34 Tourism Nation Promotion Act (Act No. 117, December 20, 2006) (extract) (Annual reports, others) Article 8: The government shall every year present to the Diet a report related to the tourism situation and its policies for realization of Japan as a tourism nation. 2. The government shall every year, based on opinions obtained from the Transport Screening Committee, prepare documents elucidating prospective policy, and present to the Diet reports taking into account the preceding Paragraph's report-related tourism situation Current Status of Tourism in FY2006 Part I New Strategies for a Tourism Nation Chapter 1 Establishment of the Tourism Nation Promotion Act Section 1 Background to the Enactment of the Tourism Nation Promotion Act In the 43 years since the Tourism Basic Act was enacted, the circumstances surrounding tourism in Japan have changed dramatically. -

Around Tokyo Fukushima

Japan Things to see, do, and experience trip from the metropolis Discover the Heart of Japan Adventures AROUND TOKYO FUKUSHIMA IBARAKI TOCHIGI GUNMA CHIBA SAITAMA TOKYO KANAGAWA NIIGATA YAMANASHI NAGANO Discover the Heart of Japan Adventures AROUND TOKYO Tokyo is a popular place to begin your journey in Japan, but in its surrounding regions you’ll fi nd some of the best scenery in the nation, delicious foods and beverages, and old traditions still alive. Fortunately, Japan’s excellent transportation network makes it very easy to venture out of the metropolis, either for a day trip or an extended adventure, and to discover some truly unique sights in these areas. Inside this photo storybook, learn about the many facets of these regions (organized by theme) and gain inspiration to create your own custom adventure. There’s something for everyone. Those fascinated by the nation’s long history can experience Japanese religious traditions or participate in traditional arts and crafts. Those eager to delve into more current topics can dis- cover the taste of Japanese wine, explore the future of high- speed rail, or learn about the nation’s preeminence in science and NIIGATA technology. The various topics introduced here are merely a few examples of the many attractive aspects of the regions around Tokyo. We hope that you will be inspired to discover the incredi- ble opportunities that await. TOYAMA ISHIKAWA GUNMA NAGANO FUKUI GIFU YAMANASHI TOTTORI SHIMANE KYOTO SHIGA SHIZUOKA HYOGO AICHI OKAYAMA HIROSHIMA OSAKA MIE NARA YAMAGUCHI KAGAWA EHIME -

Japanese 100 Great Mountains Vol.3: Episode 011-015

Japanese 100 Great Mountains Vol.3: Episode 011-015 Originally written in Japanese and translated by Hodaka Photographs by Hodaka Cover design by Tanya Copyright © 2018 Hodaka / The BBB: Breakthrough Bandwagon Books All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-0-359-12577-7 The BBB website http://thebbb.net/ Hodaka Author Page http://thebbb.net/cast/hodaka.html Episode 011: Mount Daibosatsu Mount Daibosatsu with an altitude of 2,057 meters, one of Japanese 100 Great Mountains, is located in Yamanashi Prefecture. So, it is easy to access from Tokyo. The mountain is known for its magnificent view of Mount Fuji. This is my third time to climb the mountain. At the first and second visits, I couldn’t see Mount Fuji clearly due to thick clouds. But this time, on a fine day in February (2018), I can finally see a satisfying scenery. Its snow-covered summit, unique to winter, pleases my eyes. Originally, I planned to go by car to the Kaminikkawa Pass near the summit from the Daibosatsu Pass starting point. But the road was closed during the winter. So, I had changed the plan and decided to choose the route via the Marukawa Pass to the summit. When I arrive there at around 6 am, a few vehicles have already parked. Before the departure, I have talked with the driver of the car arriving right after me about today’s weather and the course we choose. Then, we proceed to the different courses. I am walking through a forest zone with a relatively steep slope for a while. -

Minakami Perfect Travel Guide &

N 4 One Drop Outdoor Guide Service N 9 S 5 English /Enjoy/ /Enjoy/ This popular tour uses inflatable rafts for canoeing around Lake Shima, which is one of the most transparent lakes in Nature the Kanto region. Snow Enjoy activities where you can experience the Enjoy natural snow close to the Tokyo MAP B-3 Wi-Fi richness of nature. Even first-timers can feel at ease metropolitan area. In addition to eight ski resorts, MINAKAMI 0278-72-8136 with rental equipment and experienced guides. 2230-1 Kamimoku, Minakami-machi there is also a variety of other activities. 8:00-18:00 Closed Open daily during the season Perfect Travel Guide & Map onedrop-outdoor.com/ N 1 Minakami Bungy N 5 Norn Minakami Ski Resort S 1 Tanigawadake Tenjindaira Ski Resort Wi-Fi Minakami Mountain Guide Association MAP A-2 This ski resort offers novice to expert Try bungee jumping from the MAP B-3 This ski resort offers gorgeous views of the Tanigawa 0278-72-3575 level trails and Snow Land, an area which Yubiso, Yubukiyama- 42-meter-high Suwakyo Ohashi Bridge mountain range. It is known for its long ski season, Hiking and trekking on Mount Tanigawa, Oze, 0278-62-0401 offers fun in the snow for everyone. Kokuyurin, Minakami-machi over the Tone River. 1744-1 Tsukiyono, lasting from early December to early May. Some areas December to March: and Mount Hotaka are offered here. One of the most Minakami-machi MAP A-3 Wi-Fi have snow as deep as four meters during the high 8:30-16:30 (final lift at popular activities is the eco-hiking tour from Mount 8:30-17:30 16:00), April to end of Tanigawa to Ichinokurasawa, one of Japan's three Closed Open daily during season, offering the ultimate powder skiing without any MAP B-1 0278-72-6688 479-139 Terama, Minakami-machi season: 8:00-17:00 (from greatest rocks, and hiking up Mount Tanigawa with its the season Mid-December to late March: 8:00-16:00 manmade snow. -

Japanese 100 Great Mountains Vol.2: Episode 006-010

Japanese 100 Great Mountains Vol.2: Episode 006-010 Originally written in Japanese and translated by Hodaka Photographs by Hodaka Cover design by Tanya Copyright © 2018 Hodaka / The BBB: Breakthrough Bandwagon Books All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-1-387-70478-1 The BBB website http://thebbb.net/ Hodaka Author Page http://thebbb.net/cast/hodaka.html Episode 006: Mount Aizu-Komagatake Ten days after I climbed Mount Amagi in July 2017, I head for Mount Aizu-Komagatake with an altitude of 2,133 meters in Fukushima Prefecture. Located to the north of Oze National Park, Aizu-Komagatake is a mountain like a paradise because it has grand moors on its summit and is dotted with ponds and alpine plants. The reason for mountaineering at this timing is that the man whom I met at Mount Amagi (refer to Episode 004) said he would climb Mount Aizu-Komagatake on the day. He also said he needed 17 more mountains to conquer all of Japanese 100 Great Mountains. So, I have decided to try to take him by surprise. I come here today to present foods and drinks to him, because he said he would keep climbing in the Kanto region for a while. Access to Mount Aizu-Komagatake is not good. The local streets after I got off the highway continued on and on. I drove two more hours on rural roads and entered Hinoemata Village, which had an atmosphere of Japanese typical hometown. Since I departed Tokyo last night and spent the night in the car, I have arrived at a parking lot beside a starting point of mountaineering before 5 am. -

Kuniyasu Mokudai Malcolm Cooper · Mahito Watanabe Shamik Chakraborty Editors

Geoheritage, Geoparks and Geotourism Abhik Chakraborty · Kuniyasu Mokudai Malcolm Cooper · Mahito Watanabe Shamik Chakraborty Editors Natural Heritage of Japan Geological, Geomorphological, and Ecological Aspects Geoheritage, Geoparks and Geotourism Conservation and Management Series Series editors Wolfgang Eder, Munich, Germany Peter T. Bobrowsky, Burnaby, BC, Canada Jesu´s Martı´nez-Frı´as, Madrid, Spain Spectacular geo-morphological landscapes and regions with special geological features or mining sites are becoming increasingly recognized as critical areas to protect and conserve for the unique geoscientific aspects they represent and as places to enjoy and learn about the science and history of our planet. More and more national and international stakeholders are engaged in projects related to “Geoheritage”, “Geo-conservation”, “Geoparks” and “Geotourism”; and are positively influencing the general perception of modern Earth Sciences. Most notably, “Geoparks” have proven to be excellent tools to educate the public about Earth Sciences; and they are also important areas for recreation and significant sustain- able economic development through geotourism. In order to develop further the understanding of Earth Sciences in general and to elucidate the importance of Earth Sciences for Society, the “Geoheritage, Geoparks and Geotourism Conservation and Management Series” has been launched together with its sister “GeoGuides” series. Projects developed in partnership with UNESCO, World Heritage and Global Geoparks Networks, IUGS and IGU, as well as with the ‘Earth Science Matters’ Foundation will be considered for publication. This series aims to provide a place for in-depth presentations of developmental and management issues related to Geoheritage and Geotourism in existing and potential Geoparks. Individually authored monographs as well as edited volumes and conference proceedings are welcome; and this book series is considered to be complementary to the Springer-Journal “Geoheritage”. -

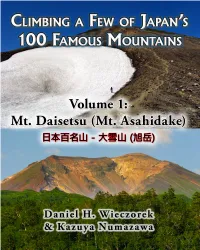

Climbing a Few of Japan's 100 Famous Mountains – Volume 4: Mt

COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL Climbing a Few of Japan’s 100 Famous Mountains – Volume 4: Mt. Hakkoda & Mt. Zao Daniel H. Wieczorek and Kazuya Numazawa COPYRIGHTEDMATERIAL Climbing a Few of Japan’s 100 Famous Mountains – Volume 4: Mt. Hakkoda & Mt. Zao COPYRIGHTEDMATERIAL Copyright © 2014 Daniel H. Wieczorek and Kazuya Numazawa All rights reserved. ISBN-10: 0996216162 ISBN-13: 978-0-9962161-6-6 DEDICATION This work is dedicated, first of all, to my partner, Kazuya Numa- zawa. He always keeps my interest in photography up and makes me keep striving for the perfect photo. He also often makes me think of the expression “when the going gets tough, the tough keep going.” Without my partner it has to also be noted that I most likely would not have climbed any of these mountains. Secondly, it is dedicated to my mother and father, bless them, for tolerating and even encouraging my photography hobby from the time I was twelve years old. And, finally, it is dedicated to my friends who have encouraged me to create books of photographs which I have taken while doing mountain climbing. COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL Other Books in this Series “Climbing a Few of Japan's 100 Famous Mountains – Volume 1: Mt. Daisetsu (Mt. Asahidake)”; ISBN-13: 9781493777204; 66 Pages; Dec. 5, 2013 “Climbing a Few of Japan's 100 Famous Mountains – Volume 2: Mt. Chokai (Choukai)”; ISBN-13: 9781494368401; 72 Pages; Dec. 8, 2013 “Climbing a Few of Japan's 100 Famous Mountains – Volume 3: Mt. Gassan”; ISBN-13: 9781494872175; 70 Pages; Jan. 4, 2014 “Climbing a Few of Japan's 100 Famous Mountains – Volume 5: Mt. -

Mt. Asahidake)

Climbing a Few of Japan’s 100 Famous Mountains – Volume 1: Mt. Daisetsu (Mt. Asahidake) Daniel H. Wieczorek and Kazuya Numazawa COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL Climbing a Few of Japan’s 100 Famous Mountains – Volume 1: Mt. Daisetsu (Mt. Asahidake) COPYRIGHTEDMATERIAL Copyright © 2014 Daniel H. Wieczorek and Kazuya Numazawa All rights reserved. ISBN: 1493777203 ISBN-13: 978-1493777204 DEDICATION This work is dedicated, first of all, to my Secondly, it is dedicated to my mother and partner, Kazuya Numazawa. He always keeps father, bless them, for tolerating and even my interest in photography up and makes me encouraging my photography hobby from the keep striving for the perfect photo. He also time I was 12 years old. often makes me think of the expression “when the going gets tough, the tough keep going.” And, finally, it is dedicated to my friends who Without my partner it has to also be noted have encouraged me to create books of that I most likely would not have climbed any photographs which I have taken while doing of these mountains. mountain climbing. COPYRIGHTEDMATERIAL Other books by Daniel H. Wieczorek and Kazuya Numazawa “Outdoor Photography of Japan: Through the Seasons”; ISBN/EAN13: 146110520X / 9781461105206; 362 Pages; June 10, 2011; Also available as a Kindle Edition “Some Violets of Eastern Japan”; ISBN/EAN13: 1463767684 / 9781463767686; 104 Pages; August 20, 2011; Also available as a Kindle Edition “2014 Photo Calendar – Japan's Flowers, Plants & Trees”; ISBN/EAN13: 1482315203 / 978- 1482315202; 30 Pages; February 4, 2013 “2014 Photo Calendar – Japan Mountain Scenery”; ISBN/EAN13: 1482371383 / 978- 1482371383; 30 Pages; February 15, 2013 Other books by Daniel H. -

Mt. Shirane (Kusatsu)

Climbing a Few of Japan’s 100 Famous Mountains – Volume 6: Mt. Shirane (Kusatsu) Daniel H. Wieczorek and Kazuya Numazawa COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL Climbing a Few of Japan’s 100 Famous Mountains – Volume 6: Mt. Shirane (Kusatsu) COPYRIGHTEDMATERIAL Copyright © 2014 Daniel H. Wieczorek and Kazuya Numazawa All rights reserved. ISBN: 1497303230 ISBN-13: 978-1497303232 DEDICATION This work is dedicated, first of all, to my Secondly, it is dedicated to my mother and partner, Kazuya Numazawa. He always keeps father, bless them, for tolerating and even my interest in photography up and makes me encouraging my photography hobby from the keep striving for the perfect photo. He also time I was 12 years old. often makes me think of the expression “when the going gets tough, the tough keep going.” And, finally, it is dedicated to my friends who Without my partner it has to also be noted have encouraged me to create books of that I most likely would not have climbed any photographs which I have taken while doing of these mountains. mountain climbing. COPYRIGHTEDMATERIAL Other books by Daniel H. Wieczorek and Kazuya Numazawa “Outdoor Photography of Japan: Through the Seasons”; ISBN/EAN13: 146110520X / 9781461105206; 362 Pages; June 10, 2011; Also available as a Kindle Edition “Some Violets of Eastern Japan”; ISBN/EAN13: 1463767684 / 9781463767686; 104 Pages; August 20, 2011; Also available as a Kindle Edition “2014 Photo Calendar – Japan's Flowers, Plants & Trees”; ISBN/EAN13: 1482315203 / 978- 1482315202; 30 Pages; February 4, 2013 “2014 Photo Calendar – Japan Mountain Scenery”; ISBN/EAN13: 1482371383 / 978- 1482371383; 30 Pages; February 15, 2013 “Climbing a Few of Japan's 100 Famous Mountains – Volume 1: Mt. -

Minakami Perfect Travel Guide & Map A2 En.Indd

N 4 One Drop Outdoor Guide Service N 9 S 5 English /Enjoy/ /Enjoy/ This popular tour uses inflatable rafts for canoeing around Lake Shima, which is one of the most transparent lakes in Nature the Kanto region. Snow Enjoy activities where you can experience the Enjoy natural snow close to the Tokyo MAP B-3 Wi-Fi richness of nature. Even first-timers can feel at ease 0278-72-8136 metropolitan area. In addition to eight ski resorts, MINAKAMI with rental equipment and experienced guides. 2230-1 Kamimoku, Minakami-machi there is also a variety of other activities. 8:00-18:00 Closed Open daily during the season onedrop-outdoor.com/ Perfect Travel Guide & Map N 1 Minakami Bungy N 5 Norn Minakami Ski Resort S 1 Tanigawadake Tenjindaira Ski Resort Wi-Fi MAP A-2 Minakami Mountain Guide Association This ski resort offers novice to expert Try bungee jumping from the MAP This ski resort offers gorgeous views of the Tanigawa 0278-72-3575 B-3 level trails and Snow Land, an area which 42-meter-high Suwakyo Ohashi Bridge Yubiso, Yubukiyama- Hiking and trekking on Mount Tanigawa, Oze, 0278-62-0401 offers fun in the snow for everyone. mountain range. It is known for its long ski season, Kokuyurin, Minakami-machi over the Tone River. 1744-1 Tsukiyono, lasting from early December to early May. Some areas December to March: and Mount Hotaka are offered here. One of the most Minakami-machi MAP A-3 Wi-Fi have snow as deep as four meters during the high 8:30-16:30 (final lift at popular activities is the eco-hiking tour from Mount 8:30-17:30 16:00), April to end of Tanigawa to Ichinokurasawa, one of Japan's three Closed Open daily during season, offering the ultimate powder skiing without any MAP B-1 0278-72-6688 479-139 Terama, Minakami-machi season: 8:00-17:00 (from greatest rocks, and hiking up Mount Tanigawa with its the season Mid-December to late March: 8:00-16:00 manmade snow.