Arxiv:1910.14462V1 [Math.HO] 30 Oct 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Point of Concurrency the Three Perpendicular Bisectors of a Triangle Intersect at a Single Point

3.1 Special Segments and Centers of Classifications of Triangles: Triangles By Side: 1. Equilateral: A triangle with three I CAN... congruent sides. Define and recognize perpendicular bisectors, angle bisectors, medians, 2. Isosceles: A triangle with at least and altitudes. two congruent sides. 3. Scalene: A triangle with three sides Define and recognize points of having different lengths. (no sides are concurrency. congruent) Jul 249:36 AM Jul 249:36 AM Classifications of Triangles: Special Segments and Centers in Triangles By angle A Perpendicular Bisector is a segment or line 1. Acute: A triangle with three acute that passes through the midpoint of a side and angles. is perpendicular to that side. 2. Obtuse: A triangle with one obtuse angle. 3. Right: A triangle with one right angle 4. Equiangular: A triangle with three congruent angles Jul 249:36 AM Jul 249:36 AM Point of Concurrency The three perpendicular bisectors of a triangle intersect at a single point. Two lines intersect at a point. The point of When three or more lines intersect at the concurrency of the same point, it is called a "Point of perpendicular Concurrency." bisectors is called the circumcenter. Jul 249:36 AM Jul 249:36 AM 1 Circumcenter Properties An angle bisector is a segment that divides 1. The circumcenter is an angle into two congruent angles. the center of the circumscribed circle. BD is an angle bisector. 2. The circumcenter is equidistant to each of the triangles vertices. m∠ABD= m∠DBC Jul 249:36 AM Jul 249:36 AM The three angle bisectors of a triangle Incenter properties intersect at a single point. -

Median and Altitude of a Triangle Goal: • to Use Properties of the Medians

Median and Altitude of a Triangle Goal: • To use properties of the medians of a triangle. • To use properties of the altitudes of a triangle. Median of a Triangle Median of a Triangle – a segment whose endpoints are the vertex of a triangle and the midpoint of the opposite side. Vertex Median Median of an Obtuse Triangle A D Point of concurrency “P” or centroid E P C B F Medians of a Triangle The medians of a triangle intersect at a point that is two-thirds of the distance from each vertex to the midpoint of the opposite side. A D If P is the centroid of ABC, then AP=2 AF E 3 P C CP=22CE and BP= BD B F 33 Example - Medians of a Triangle P is the centroid of ABC. PF 5 Find AF and AP A D E P C B F 5 Median of an Acute Triangle A Point of concurrency “P” or centroid E D P C B F Median of a Right Triangle A F Point of concurrency “P” or centroid E P C B D The three medians of an obtuse, acute, and a right triangle always meet inside the triangle. Altitude of a Triangle Altitude of a triangle – the perpendicular segment from the vertex to the opposite side or to the line that contains the opposite side A altitude C B Altitude of an Acute Triangle A Point of concurrency “P” or orthocenter P C B The point of concurrency called the orthocenter lies inside the triangle. Altitude of a Right Triangle The two legs are the altitudes A The point of concurrency called the orthocenter lies on the triangle. -

Exploring Some Concurrencies in the Tetrahedron

Exploring some concurrencies in the tetrahedron Consider the corresponding analogues of perpendicular bisectors, angle bisectors, medians and altitudes of a triangle for a tetrahedron, and investigate which of these are also concurrent for a tetrahedron. If true, prove it; if not, provide a counter-example. Let us start with following useful assumption (stated without proof) for 3D: Three (non-parallel) planes meet in a point. (It is easy to see this in a rectangular room where two walls and the ceiling meet perpendicularly in a point.) Definition 1: The perpendicular edge bisector is the A generalisation to 3D of the concept of a perpendicular bisector. For example, the perpendicular edge bisector of AB is the plane through the midpoint of AB, and perpendicular D to it. Or equivalently, it is the set of points equidistant from A and B. B Theorem 1: The six perpendicular edge bisectors of a C tetrahedron all meet at the circumcentre. Proof: Let S be the intersection of the three perpendicular edge bisectors of AB, BC, CD. Therefore SA = SB = SC = SD. Therefore S must lie on all 6 perpendicular edge bisectors, and the sphere, centre S and radius SA, goes through all four vertices. Definition 2: Let a, b, c, d denote the four faces of a A tetrahedron ABCD. The face angle bisector of ab is the plane through CD bisecting the angle between b the faces a, b. It is therefore also the set of points equidistant from a and b. D a Theorem 2: The six face angle bisectors of a B tetrahedron all meet at the incentre. -

Midpoints and Medians in Triangles

MPM1D Midpoints and Medians in Triangles Midpoint: B A C 1) Use a ruler to create a midpoint for AB. Label it X. 2) Use a ruler to create a midpoint for AC. Label it Y. 3) Join the points X and Y with a line. 4) Measure all the sides. Write them on the diagram. Q: What do you notice about the lenGth of XY and BC? Q: What do you notice about the direction of the lines XY and BC? Q: How could we prove this? The line seGments joining the midpoint of two sides of a triangle is _________________________ the third side and ___________________________ . Recall: The area of a trianGle is: � = Median: A line from one vertex to the midpoint of the opposite side. A B C 1) Draw the midpoint of BC, label it M 2) Draw the median from A to BC 3) Calculate the area of rABM and rAMC (MeasurinG any lenGths you need to find the area) Medians of a trianGle ________ its area. Example 2 The area of rXYZ is 48 ��(. A median is drawn from X, and the midpoint of the opposite side is labelled M. What is the area of rXYM? 1. Find the length of line segment MN in each triangle. a) b) c) d) 2. Find the lengths of line segments AD and DE in each triangle. a) b) c) d) 3. The area of rABC is 10 cm2. Calculate the area of each triangle. a) rABD b) rADC 4. Calculate the area of each triangle given the area of rMNQ is 12 cm2. -

The Euler Line in Non-Euclidean Geometry

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2003 The Euler Line in non-Euclidean geometry Elena Strzheletska Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Mathematics Commons Recommended Citation Strzheletska, Elena, "The Euler Line in non-Euclidean geometry" (2003). Theses Digitization Project. 2443. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/2443 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE EULER LINE IN NON-EUCLIDEAN GEOMETRY A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Mathematics by Elena Strzheletska December 2003 THE EULER LINE IN NON-EUCLIDEAN GEOMETRY A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Elena Strzheletska December 2003 Approved by: Robert Stein, Committee Member Susan Addington, Committee Member Peter Williams, Chair Terry Hallett, Department of Mathematics Graduate Coordinator Department of Mathematics ABSTRACT In Euclidean geometry, the circumcenter and the centroid of a nonequilateral triangle determine a line called the Euler line. The orthocenter of the triangle, the point of intersection of the altitudes, also belongs to this line. The main purpose of this thesis is to explore the conditions of the existence and the properties of the Euler line of a triangle in the hyperbolic plane. -

January 2009

How Euler Did It by Ed Sandifer The Euler line January 2009 A hundred years ago, if you'd asked people why Leonhard Euler was famous, those who had an answer would very likely have mentioned his discovery of the Euler line, the remarkable property that the orthocenter, the center of gravity and the circumcenter of a triangle are collinear. But times change, and so do fashions and the standards by which we interpret history. At the end of the nineteenth century, triangle geometry was regarded as one of the crowning achievements of mathematics, and the Euler line was one of its finest jewels. Mathematicians who neglected triangle geometry to study exotic new fields like logic, abstract algebra or topology were taking brave risks to their professional careers. Now it would be the aspiring triangle geometer taking the risks. Still, the late H. S. M. Coxeter made a long and distinguished career without straying far from the world of triangles, and he introduced hundreds of others to their delightful properties, especially the Euler line. This month, we look at how Euler discovered the Euler line and what he was trying to do when he discovered it. We will find that the discovery was rather incidental to the problem he was trying to solve, and that the problem itself was otherwise rather unimportant. This brings us to the 325th paper in Gustav Eneström's index of Euler's published work, "Solutio facilis problematum quorumdam geometricorum difficillimorum" (An easy solution to a very difficult problem in geometry) [E325]. Euler wrote the paper in 1763 when he lived in Berlin and worked at the academy of Frederick the Great. -

Volume 3 2003

FORUM GEOMETRICORUM A Journal on Classical Euclidean Geometry and Related Areas published by Department of Mathematical Sciences Florida Atlantic University b bbb FORUM GEOM Volume 3 2003 http://forumgeom.fau.edu ISSN 1534-1178 Editorial Board Advisors: John H. Conway Princeton, New Jersey, USA Julio Gonzalez Cabillon Montevideo, Uruguay Richard Guy Calgary, Alberta, Canada George Kapetis Thessaloniki, Greece Clark Kimberling Evansville, Indiana, USA Kee Yuen Lam Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada Tsit Yuen Lam Berkeley, California, USA Fred Richman Boca Raton, Florida, USA Editor-in-chief: Paul Yiu Boca Raton, Florida, USA Editors: Clayton Dodge Orono, Maine, USA Roland Eddy St. John’s, Newfoundland, Canada Jean-Pierre Ehrmann Paris, France Lawrence Evans La Grange, Illinois, USA Chris Fisher Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada Rudolf Fritsch Munich, Germany Bernard Gibert St Etiene, France Antreas P. Hatzipolakis Athens, Greece Michael Lambrou Crete, Greece Floor van Lamoen Goes, Netherlands Fred Pui Fai Leung Singapore, Singapore Daniel B. Shapiro Columbus, Ohio, USA Steve Sigur Atlanta, Georgia, USA Man Keung Siu Hong Kong, China Peter Woo La Mirada, California, USA Technical Editors: Yuandan Lin Boca Raton, Florida, USA Aaron Meyerowitz Boca Raton, Florida, USA Xiao-Dong Zhang Boca Raton, Florida, USA Consultants: Frederick Hoffman Boca Raton, Floirda, USA Stephen Locke Boca Raton, Florida, USA Heinrich Niederhausen Boca Raton, Florida, USA Table of Contents Bernard Gibert, Orthocorrespondence and orthopivotal cubics,1 Alexei Myakishev, -

The Euler Line in Hyperbolic Geometry

The Euler Line in Hyperbolic Geometry Jeffrey R. Klus Abstract- In Euclidean geometry, the most commonly known system of geometry, a very interesting property has been proven to be common among all triangles. For every triangle, there exists a line that contains three major points of concurrence for that triangle: the centroid, orthocenter, and circumcenter. The centroid is the concurrence point for the three medians of the triangle. The orthocenter is the concurrence point of the altitudes. The circumcenter is the point of concurrence of the perpendicular bisectors of each side of the triangle. This line that contains these three points is called the Euler line. This paper discusses whether or not the Euler line exists in Hyperbolic geometry, an alternate system of geometry. The Poincare Disc Model for Hyperbolic geometry, together with Geometer’s Sketchpad software package was used extensively to answer this question. Introduction In Euclidean geometry, the most Second, for any circle that is orthogonal commonly known system of geometry, a to the unit circle, the points on that circle very interesting property has been lying in the interior of the unit circle will proven to be common among all be considered a hyperbolic line triangles. For every triangle, there exists (Wallace, 1998, p. 336). a line that contains three major points of concurrence for that triangle: the Methods centroid, orthocenter, and circumcenter. Locating the Centroid The centroid is the concurrence point for In attempting to locate the Euler line, the the three medians of the triangle. The first thing that needs to be found is the orthocenter is the concurrence point of midpoint of each side of the hyperbolic the altitudes. -

Along Euler's Line, Part I

Plane Geometry I, II, III: Along the Euler Line Berkeley Math Circle { Beginners by Zvezdelina Stankova Berkeley Math Circle Director September 6, 13, 20 2011 Note: We shall work on the problems below over first three circle sessions of BMC-beginners. Bring this handout with you to all three sessions. Try to understand what the problems say and draw pictures for them as best as you can. You are not expected to be able to solve the problems on your own, at least not in the beginning of this Geometry module at BMC{beginners. Bring drawing tools to the sessions too: compass, ruler, triangles, protractor, pencils, erasers. 1. A Bit of Related History (adapted from Wikipedia) Leonhard Euler (15 April 1707 { 18 September 1783) was a pioneering Swiss mathematician and physicist. He made important discoveries in fields as diverse as infinitesimal calculus and graph theory. He also introduced much of the modern mathematical terminology and notation, particularly for mathematical analysis, such as the notion of a mathematical function: he was the first to write f(x) to denote the function f applied to the argument x. He also introduced the modern notation for the trigonometric functions, the letter e for the base of the natural logarithm (now also known as Euler's number), the Greek letter Σ for summations and the letter i to denote the imaginary unit. The use of the Greek letter π to denote the ratio of a circle's circumference to its diameter was also popularized by Euler, although it did not originate with him. He is also renowned for his work in mechanics, fluid dynamics, optics, and astronomy. -

5.4 Medians and Altitudes

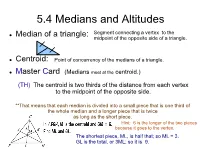

5.4 Medians and Altitudes Segment connecting a vertex to the Median of a triangle: midpoint of the opposite side of a triangle. Centroid: Point of concurrency of the medians of a triangle. Master Card (Medians meet at the centroid.) (TH) The centroid is two thirds of the distance from each vertex to the midpoint of the opposite side. **That means that each median is divided into a small piece that is one third of the whole median and a longer piece that is twice as long as the short piece. Hint: 6 is the longer of the two pieces because it goes to the vertex. The shortest piece, ML, is half that; so ML = 3. GL is the total, or 3ML; so it is 9. Altitude: The perpendicular segment connecting a vertex to the line containing the opposite side of the triangle. The altitude can be inside the triangle. (all three altitudes in acute triangles.) pics drawn on board. The altitude can be a side of the triangle. (two of the altitudes in a right triangle.) The altitude can be outside the triangle. (two of the altitudes in an obtuse triangle.) Orthocenter: The point of concurrency of the altitudes. Atlantic Ocean Current: Altitudes meet at the Orthocenter. The theorem for altitudes only says that they are concurrent. Hint: Find the median of one side and use the Centroid theorem. The centroid is two thirds from point K to point M. P(4,4) Hint: draw a picture and state the given and prove. Since BD is an altitude, we have two right triangles with a reflexive leg. -

3.3 -3.4 More Triangle Parts and Properties

3.3 -3.4 More Triangle Parts and Properties Base and altitude Every triangle has three bases (any of its sides) and three altitudes (heights). Every altitude is the perpendicular segment from a vertex to its opposite side (or the extension of the opposite side) (Figure 1). Figure 1 Altitudes can sometimes coincide with a side of the triangle or can sometimes meet an extended base outside the triangle. In Figure 2, AC is an altitude to base BC , and BC is an altitude to base AC . Figure 2 In a right triangle, each leg can serve as an altitude. It is interesting to note that in any triangle, the three lines containing the altitudes meet in one point (Figure 4). 3.3 -3.4 More Triangle Parts and Properties Figure 4 The three lines containing the altitudes intersect in a single point, which may or may not be inside the triangle. This point is called the orthocenter. Median A median in a triangle is the line segment drawn from a vertex to the midpoint of its opposite side. Every triangle has three medians. In Figure 5, E is the midpoint of BC . Therefore, BE = EC. AE is a median of Δ ABC. Figure 5 A median of a triangle. In every triangle, the three medians meet in one point inside the triangle (Figure 6). Figure 6 The three medians meet in a single point inside the triangle. This point is called the Centroid. Angle bisector An angle bisector in a triangle is a segment drawn from a vertex that bisects (cuts in half) that vertex angle. -

Using Triangle Centers to Create Similar Or Congruent Triangles Kathryn E

Valparaiso University ValpoScholar Mathematics and Statistics Faculty Publications Department of Mathematics and Statistics 2016 New Findings in Old Geometry: Using Triangle Centers to Create Similar or Congruent Triangles Kathryn E. Lezark Valparaiso University, [email protected] Mindy B. Capaldi Valparaiso University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.valpo.edu/math_stat_fac_pubs Recommended Citation Lezark, K., Capaldi, M. (2016). New findings in old geometry: Using triangle centers to create similar or congruent triangles. The Minnesota Journal of Undergraduate Mathematics, 2(1). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Mathematics and Statistics at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mathematics and Statistics Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. The Minnesota Journal of Undergraduate Mathematics New Findings in Old Geometry: using triangle centers to create similar or congruent triangles Kathryn Lezark ∗ and Mindy Capaldi Valparaiso University The Minnesota Journal of Undergraduate Mathematics Volume 2 Number 1 (2016) Sponsored by School of Mathematics University of Minnesota Minneapolis, MN 55455 MJUM Vol. 2 No. 1 (2016) Page 1 The Minnesota Journal of Undergraduate Mathematics Volume 2 Number 1 (2016) New Findings in Old Geometry: using triangle centers to create similar or congruent triangles Kathryn Lezark ∗ and Mindy Capaldi Valparaiso University Abstract. The Euler line of a triangle passes through several important points, including three specific triangle centers: the centroid, orthocenter, and circumcenter. Each of these centers is the intersection of lines related to the triangle, mainly its medians, altitudes, and perpendicular bisectors, respectively.