Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tonto National Forest Travel Management Plan

Comments on the DEIS for the Tonto National Forest Travel Management Plan Submitted September 15, 2014 via Electronic Mail and Certified Mail #7014-0150-0001-2587-0812 On Behalf of: Archaeology Southwest Center for Biological Diversity Sierra Club The Wilderness Society WildEarth Guardians Table of Contents II. Federal Regulation of Travel Management .................................................................................. 4 III. Impacts from Year Round Motorized Use Must be Analyzed .................................................. 5 IV. The Forest Service’s Preferred Alternative .............................................................................. 6 V. Desired Conditions for Travel Management ................................................................................. 6 VI. Purpose and Need Statements ................................................................................................... 7 VII. Baseline Determination .............................................................................................................. 8 A. The Forest Service cannot arbitrarily reclassify roads as “open to motor vehicle use” in the baseline. ............................................................................................................................................ 10 B. Classification of all closed or decommissioned routes as “open to motor vehicle use” leads to mischaracterization of the impacts of the considered alternatives. ...................................................... 11 C. Failure -

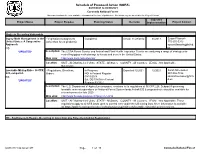

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 04/01/2021 to 06/30/2021 Coronado National Forest This Report Contains the Best Available Information at the Time of Publication

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 04/01/2021 to 06/30/2021 Coronado National Forest This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact Projects Occurring Nationwide Gypsy Moth Management in the - Vegetation management Completed Actual: 11/28/2012 01/2013 Susan Ellsworth United States: A Cooperative (other than forest products) 775-355-5313 Approach [email protected]. EIS us *UPDATED* Description: The USDA Forest Service and Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service are analyzing a range of strategies for controlling gypsy moth damage to forests and trees in the United States. Web Link: http://www.na.fs.fed.us/wv/eis/ Location: UNIT - All Districts-level Units. STATE - All States. COUNTY - All Counties. LEGAL - Not Applicable. Nationwide. Locatable Mining Rule - 36 CFR - Regulations, Directives, In Progress: Expected:12/2021 12/2021 Sarah Shoemaker 228, subpart A. Orders NOI in Federal Register 907-586-7886 EIS 09/13/2018 [email protected] d.us *UPDATED* Est. DEIS NOA in Federal Register 03/2021 Description: The U.S. Department of Agriculture proposes revisions to its regulations at 36 CFR 228, Subpart A governing locatable minerals operations on National Forest System lands.A draft EIS & proposed rule should be available for review/comment in late 2020 Web Link: http://www.fs.usda.gov/project/?project=57214 Location: UNIT - All Districts-level Units. STATE - All States. COUNTY - All Counties. LEGAL - Not Applicable. These regulations apply to all NFS lands open to mineral entry under the US mining laws. -

Socioeconomic Assessment for the Tonto National Forest

4. Access and Travel Patterns This section examines historic and current factors affecting access patterns and transportation infrastructure within the four counties surrounding Tonto National Forest (TNF). The information gathered is intended to outline current and future trends in forest access as well as potential barriers to access encountered by various user groups. Primary sources of data on access and travel patterns for the state’s national forests include the Arizona Department of Transportation (ADOT), the Arizona Department of Commerce (ADOC), and the circulation elements of individual county comprehensive plans. Indicators used to assess access and travel patterns include existing road networks and planned improvements, trends in vehicle miles traveled (VMT) on major roadways, seasonal traffic flows, and county transportation planning priorities. Additional input on internal access issues has been sought directly from forest planning staff. Various sources of information for the area surrounding TNF cite the difficulty of transportation planning in the region given its vast geographic scale, population growth, pace of development, and constrained transportation funding. In an effort to respond effectively to such challenges, local and regional planning authorities stress the importance of linking transportation planning with preferred land uses. Data show that the area surrounding Tonto National Forest saw relatively large increases in VMT between 1990 and 2000, mirroring the region’s relatively strong population growth over the same period. Information gathered from the Arizona Department of Transportation (ADOT) and county comprehensive plans suggest that considerable improvements are currently scheduled for the region’s transportation network, particularly when compared to areas surrounding Arizona’s other national forests. -

USDA Forest Service Youth Conservation Corps Projects 2021

1 USDA Forest Service Youth Conservation Corps Projects 2021 Alabama Tuskegee, National Forests in Alabama, dates 6/6/2021--8/13/2021, Project Contact: Darrius Truss, [email protected] 404-550-5114 Double Springs, National Forests in Alabama, 6/6/2021--8/13/2021, Project Contact: Shane Hoskins, [email protected] 334-314- 4522 Alaska Juneau, Tongass National Forest / Admiralty Island National Monument, 6/14/2021--8/13/2021 Project Contact: Don MacDougall, [email protected] 907-789-6280 Arizona Douglas, Coronado National Forest, 6/13/2021--7/25/2021, Project Contacts: Doug Ruppel and Brian Stultz, [email protected] and [email protected] 520-388-8438 Prescott, Prescott National Forest, 6/13/2021--7/25/2021, Project Contact: Nina Hubbard, [email protected] 928- 232-0726 Phoenix, Tonto National Forest, 6/7/2021--7/25/2021, Project Contact: Brooke Wheelock, [email protected] 602-225-5257 Arkansas Glenwood, Ouachita National Forest, 6/7/2021--7/30/2021, Project Contact: Bill Jackson, [email protected] 501-701-3570 Mena, Ouachita National Forest, 6/7/2021--7/30/2021, Project Contact: Bill Jackson, [email protected] 501- 701-3570 California Mount Shasta, Shasta Trinity National Forest, 6/28/2021--8/6/2021, Project Contact: Marcus Nova, [email protected] 530-926-9606 Etna, Klamath National Forest, 6/7/2021--7/31/2021, Project Contact: Jeffrey Novak, [email protected] 530-841- 4467 USDA Forest Service Youth Conservation Corps Projects 2021 2 Colorado Grand Junction, Grand Mesa Uncomphagre and Gunnison National Forests, 6/7/2021--8/14/2021 Project Contact: Lacie Jurado, [email protected] 970-817-4053, 2 projects. -

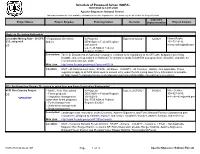

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 01/01/2021 to 03/31/2021 Tonto National Forest This Report Contains the Best Available Information at the Time of Publication

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 01/01/2021 to 03/31/2021 Tonto National Forest This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact Projects Occurring Nationwide Locatable Mining Rule - 36 CFR - Regulations, Directives, In Progress: Expected:12/2021 12/2021 Nancy Rusho 228, subpart A. Orders DEIS NOA in Federal Register 202-731-9196 09/13/2018 [email protected] EIS Est. FEIS NOA in Federal Register 11/2021 Description: The U.S. Department of Agriculture proposes revisions to its regulations at 36 CFR 228, Subpart A governing locatable minerals operations on National Forest System lands.A draft EIS & proposed rule should be available for review/comment in late 2020 Web Link: http://www.fs.usda.gov/project/?project=57214 Location: UNIT - All Districts-level Units. STATE - All States. COUNTY - All Counties. LEGAL - Not Applicable. These regulations apply to all NFS lands open to mineral entry under the US mining laws. More Information is available at: https://www.fs.usda.gov/science-technology/geology/minerals/locatable-minerals/current-revisions. R3 - Southwestern Region, Occurring in more than one Forest (excluding Regionwide) 01/01/2021 04:04 am MT Page 1 of 19 Tonto National Forest Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact R3 - Southwestern Region, Occurring in more than one Forest (excluding Regionwide) 4FRI Rim Country Project - Wildlife, Fish, Rare plants In Progress: Expected:07/2021 08/2021 Mike Dechter EIS - Forest products DEIS NOA in Federal Register 928-527-3416 - Vegetation management 10/18/2019 [email protected] (other than forest products) Est. -

Paths More Traveled: Predicting Future Recreation Pressures on America’S National Forests and Grasslands Donald B.K

United States Department of Agriculture Paths More Traveled: Predicting Future Recreation Pressures on America’s National Forests and Grasslands Donald B.K. English Pam Froemke A Forests on the Edge Report Kathleen Hawkos Forest Service FS-1034 June 2015 All photos © Thinkstock.com All photos Authors Key Words Learn More Donald B.K. English is a program Recreation, NVUM, national For further information manager for national visitor forests, population growth on this or other Forests on the Edge use monitoring; Forest Service, publications, please contact: Recreation, Heritage, and Volunteer Suggested Citation Resources Staff; Washington, DC. Anne Buckelew Pam Froemke is an information English, D.B.K.; Froemke, P.; U.S. Department of Agriculture technology specialist Hawkos, K.; 2014. Forest Service (spatial data analyst); Paths more traveled: Predicting Cooperative Forestry Staff Forest Service, Rocky Mountain future recreation pressures on 1400 Independence Avenue, SW Research Station; Fort Collins, CO. America’s national forests and Mailstop 1123 Kathleen Hawkos is a grasslands—a Forests on the Edge Washington, DC 20250–1123 cartographer/GIS specialist; report. FS-1034. Washington, DC: 202–401–4073 Forest Service, Southwestern U.S. Department of Agriculture [email protected] Regional Office, Albuquerque, NM. (USDA), Forest Service. 36 p. http://www.fs.fed.us/openspace/ Photos from front cover (top to bottom, left to right): © Thinkstock.com, © iStock.com, © Thinkstock.com, © iStock.com Paths More Traveled: Predicting Future Recreation Pressures on America’s National Forests and Grasslands A Forests on the Edge Report Learn More Abstract Populations near many national forests be expected to increase by 12 million new and grasslands are rising and are outpac- visits per year, from 83 million in 2010 to ing growth elsewhere in the United States. -

Tonto National Forest 2019 LRMP Biological Opinion

United States Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service Arizona Ecological Services Office 9828 North 31st Avenue #C3 Phoenix, Arizona 85051-2517 Telephone: (602) 242-0210 Fax: (602) 242-2513 In reply, refer to: AESO/SE 02E00000-2012-F-0011-R001/02EAAZ00-2020-F-0206 December 17, 2019 Mr. Neil Bosworth, Forest Supervisor Tonto National Forest Supervisor’s Office 2324 East McDowell Road Phoenix, Arizona 85006 RE: Continued Implementation of the Tonto National Forest’s Land and Resource Management Plan (LRMP) for the Mexican Spotted Owl and its Designated Critical Habitat Dear Mr. Bosworth: This document transmits our biological opinion (BO) for the reinitiation of formal consultation pursuant to section 7 of the Endangered Species Act of 1973 (16 U.S.C. § 1531-1544), as amended (ESA or Act), for the Tonto National Forest’s (NF) Land and Resource Management Plan (LRMP). The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) and Forest Service are conducting this reinitiation in response to a September 12, 2019, court order in WildEarth Guardians v. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 4:13-CV-00151-RCC. In response to this court order, as well as updated information regarding subjects in the BO, and current regulation and policy, we are updating the Status of the Species, Environmental Baseline, Effects of the Action, Cumulative Effects, and Incidental Take Statement sections of the April 30, 2012, Tonto NF LRMP BO (02E00000-2012-F-0011). We received your updated Biological Assessment (BA) on November 23, 2019. We are consulting on effects to the threatened Mexican spotted owl (Strix occidentalis lucida) (spotted owl or owl) and its critical habitat from the Forest Services’ continued implementation of the Tonto NF’s LRMP. -

Apache-Sitgreaves National Forests This Report Contains the Best Available Information at the Time of Publication

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 10/01/2020 to 12/31/2020 Apache-Sitgreaves National Forests This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact Projects Occurring Nationwide Locatable Mining Rule - 36 CFR - Regulations, Directives, In Progress: Expected:12/2021 12/2021 Nancy Rusho 228, subpart A. Orders DEIS NOA in Federal Register 202-731-9196 EIS 09/13/2018 [email protected] Est. FEIS NOA in Federal Register 11/2021 Description: The U.S. Department of Agriculture proposes revisions to its regulations at 36 CFR 228, Subpart A governing locatable minerals operations on National Forest System lands.A draft EIS & proposed rule should be available for review/comment in late 2020 Web Link: http://www.fs.usda.gov/project/?project=57214 Location: UNIT - All Districts-level Units. STATE - All States. COUNTY - All Counties. LEGAL - Not Applicable. These regulations apply to all NFS lands open to mineral entry under the US mining laws. More Information is available at: https://www.fs.usda.gov/science-technology/geology/minerals/locatable-minerals/current-revisions. R3 - Southwestern Region, Occurring in more than one Forest (excluding Regionwide) 4FRI Rim Country Project - Wildlife, Fish, Rare plants In Progress: Expected:07/2021 08/2021 Mike Dechter EIS - Forest products DEIS NOA in Federal Register 928-527-3416 [email protected] *UPDATED* - Vegetation management 10/18/2019 (other than forest products) Est. FEIS NOA in Federal - Fuels management Register 03/2021 - Watershed management - Road management Description: Landscape-scale restoration on the Coconino, Apache-Sitgreaves, and Tonto National Forests of ponderosa pine ecosystems, designed to maintain, improve, and restore ecosystem structure, pattern, function, and resiliency. -

Table 6 - NFS Acreage by State, Congressional District and County

Table 6 - NFS Acreage by State, Congressional District and County State Congressional District County Unit NFS Acreage Alabama 1st Escambia Conecuh National Forest 29,179 1st Totals 29,179 2nd Coffee Pea River Land Utilization Project 40 Covington Conecuh National Forest 54,881 2nd Totals 54,921 3rd Calhoun Rose Purchase Unit 161 Talladega National Forest 21,412 Cherokee Talladega National Forest 2,229 Clay Talladega National Forest 66,763 Cleburne Talladega National Forest 98,750 Macon Tuskegee National Forest 11,348 Talladega Talladega National Forest 46,272 3rd Totals 246,935 4th Franklin William B. Bankhead National Forest 1,277 Lawrence William B. Bankhead National Forest 90,681 Winston William B. Bankhead National Forest 90,030 4th Totals 181,988 6th Bibb Talladega National Forest 60,867 Chilton Talladega National Forest 22,986 6th Totals 83,853 2018 Land Areas Report Refresh Date: 10/13/2018 Table 6 - NFS Acreage by State, Congressional District and County State Congressional District County Unit NFS Acreage 7th Dallas Talladega National Forest 2,167 Hale Talladega National Forest 28,051 Perry Talladega National Forest 32,796 Tuscaloosa Talladega National Forest 10,998 7th Totals 74,012 Alabama Totals 670,888 Alaska At Large Anchorage Municipality Chugach National Forest 248,417 Haines Borough Tongass National Forest 767,952 Hoonah-Angoon Census Area Tongass National Forest 1,974,292 Juneau City and Borough Tongass National Forest 1,672,846 Kenai Peninsula Borough Chugach National Forest 1,261,067 Ketchikan Gateway Borough Tongass -

03-12-00-21-448 United States Department Of

Order Number: 03-12-00-21-448 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE FOREST SERVICE TONTO NATIONAL FOREST STAGE III FOREST CLOSURE PROHIBITIONS Pursuant to 16 U.S.C. § 551 and 36 C.F.R. § 261.50(a), the following acts are prohibited within the area described in this Order (the “Restricted Area”) and as depicted on the attached maps, hereby incorporated into this Order as Exhibits A through E, all within the Tonto National Forest, Maricopa, Pinal, Yavapai and Gila Counties, Arizona. 1. Going into or being upon the Restricted Area. 36 C.F.R.§261.52(e). EXEMPTIONS Pursuant to 36 CFR § 261.50(e), the following persons are exempt from this order: 1. Persons with a written Forest Service authorization specifically exempting them from the effect of this Order. 2. Any Federal, State, or local officer, or member of any organized rescue or firefighting resource in the performance of an official duty. 3. Residents or businesses using roads in the Restricted Area to the extent necessary to access their private property. RESTRICTED AREA All National Forest System lands contained within the boundary of the Tonto National Forest as depicted in Exhibit A, except areas listed specifically below as “open,” as further depicted in Exhibits B-E. Any open areas are still subject to current Stage 2 Fire Restrictions. The entire Forest is closed, except for the following areas and roads: Page 1 of 4 Order Number: 03-12-00-21-448 o OPEN Areas: Roosevelt Lake, within the boundary beginning at the intersection of State Route (SR) 188 and National Forest System Road (NFSR) 84 (Grapevine Road), then following north along FR 84 to the east side of Grapevine Boat Ramp at the waterline of Roosevelt Lake, then following the waterline east to the confluence of the Salt River, then following along the Roosevelt Lake waterline northwest to the confluence of Tonto Creek, then following up Tonto Creek to FR 60, then following southeast along the Roosevelt Lake waterline back to the point of beginning at the intersection of SR 188 and FR 84, as shown in Exhibit B. -

Fire Restrictions to Begin Friday on Four Arizona National Forests

NEWS RELEASE Coconino National Forest – www.fs.usda.gov/coconino Kaibab National Forest – www.fs.usda.gov/kaibab Prescott National Forest – www.fs.usda.gov/prescott Tonto National Forest – www.fs.usda.gov/tonto For Immediate Release Jacqueline Banks, 928-635-8314 April 15, 2014 Heather Noel, 928-527-3490 Debbie Maneely, 928-443-8130 David Albo, 602-525-1042 Fire Restrictions To Begin Friday On Four Arizona National Forests ARIZONA – Campfire and smoking restrictions will be implemented at 8 a.m. Friday, April 18, on the Coconino, Kaibab, Prescott and Tonto National Forests in order to protect public health and reduce preventable human-caused fires. On the Kaibab National Forest, restrictions will apply only to the Williams and Tusayan Ranger Districts. Fire restrictions will not yet be implemented on the North Kaibab Ranger District due to different weather and fuels conditions. Under the restrictions, fires, campfires, charcoal, coal and wood stoves are allowed in developed campgrounds only. The restrictions also limit smoking to within enclosed vehicles or buildings or in developed campgrounds. Using a device that is solely fueled by liquid petroleum or LPG fuels that can be turned on and off is allowed in areas that are clear of flammable materials. Fireworks are always prohibited on all national forest lands. On the Prescott National Forest, campfires are not allowed at the designated dispersed sites within the Prescott Basin. Metal posts identify designated dispersed sites with a number. Implementation of fire restrictions is especially important this year given the dry winter and impacts of long-term drought on the forests. -

View the Nationwide List of Thomas Fire Cooperating Agencies

THOMAS FIRE NATIONWIDE COOPERATING AGENCIES Alaska Alaska Fire Service Resources, Alaska Fire Service - Galena Zone, Mat-Su Area Forestry, Northern Region Office, Alaska Fire Service - Tanana Zone Arkansas Ouachita National Forest, Ozark & St. Francis National Forests Arizona Phoenix District, Flagstaff District, Tucson District, Arizona State Forestry - Central District, Arizona State Forestry - Northwest District, Avondale Fire Department, Alpine Fire District, Arizona Strip Field Office, Apache-Sitgreaves National Forest, Arizona State Forestry Division - State Office, Beaver Dam / Littlefield Fire District, Bisbee Fire Department, Bullhead City Fire Department, Benson Fire Department, Buckskin Fire District, Buckeye Fire Department, Central Arizona Fire and Medical Authority, Central Yavapai Fire District, Casa Grande Fire Department, Coronado National Forest, Coconino National Forest, Colorado River Agency, Daisy Mountain Fire Department, Arizona State Forestry Division - Deer Valley Office, Eloy Fire District, Fry Fire District, Gila District Office, Globe Fire Department, Green Valley Fire District, Golder Ranch Fire District, Greer Fire District, Heber-Overgaard Fire Department, Highlands Fire District, Kaibab National Forest, Mayer Fire District, Mohave Valley Fire Department, Navajo Region Fire and Aviation Management, North County Fire and Medical District, Nogales Fire Department, Northwest Fire Rescue District, Patagonia Volunteer Fire Department, Peoria Fire Department, Phoenix District Office, Picture Rocks Fire District,