Gender-Based Violence in Public Spaces in Skopje

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PROSPEKT ITTF NOV.Cdr

OFFICIAL BALL SUPPLIER MACED TION ONIAN TABLE TENNIS ASSOCIA ITTF JUNIOR CIRCUIT S K O P J E 8 - 1 2 O c t 2 0 1 9 OFFICIAL BALL SUPPLIER IT ITTF JUNIOR CURCU OFFICIAL BALL SUPPLIER IT ITTF JUNIOR CURCU junior players during ITTF Junior Circuit. All players will be fighting for the titles in Skopje and that OFFICIAL BALL SUPPLIER ITT RCUIT F JUNIOR CU WELCOME TO SKOPJE, Millenium Cross The Millennium Cross is tall cross situated on Krstovar on top of Mountain Vodno over the city of Skopje. The cross is 66 meters tall which makes it the tallest object in the Republic of North Macedonia. It was built in 2002. This cross was built in honor of two thousand years of Christianity in North Macedonia and the advent of the new millennium. There is also a cable car cabins that lead to the Millennium Cross and serve as a panoramic view of the city and mountains. OFFICIAL BALL SUPPLIER ITT RCUIT F JUNIOR CU WELCOME TO SKOPJE, Mother Teresa-Memorial House Спомен куќа - Мајка Тереза Skopje Fortress Скопско кале Canyon Matka Кањон Матка Canyon Matka, is like a quick gateway from all the fuss and chaos in the capital. The genuine smells of the lively green nature,combined with the poetic sounds of the load, fresh river makes an atmosphere to die for! Grabbing a bite at the Matka restaurant by the water or taking a walk across the canyon, it is always a pleasurable experience. For the zen humans-a restaurant and bout trips.For the sporty ones-canoeing on the wild river or hiking.There are 10 caves you could see and the canyon also features two vertical pits, both roughly extending 35 meters.For the history explorers-the canyon area is home to several historic churches and monasteries. -

Art 03:Mise En Page 1.Qxd

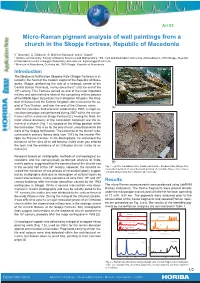

Art 03 Micro-Raman pigment analysis of wall paintings from a church in the Skopje Fortress, Republic of Macedonia V. Tanevska1, Lj. Džidrova2, B. Minčeva-Šukarova1 and O. Grupče1 1 Institute of Chemistry, Faculty of Natural Sciences and Mathematics, “SS. Cyril and Methodius” University, Arhimedova 5, 1000 Skopje, Republic of Macedonia e-mail: [email protected], [email protected] 2 Museum of Macedonia, Ćurčiska bb, 1000 Skopje, Republic of Macedonia Introduction The Mediaeval fortification Skopsko Kale (Skopje Fortress) is si- tuated in the heart of the modern capital of the Republic of Mace- donia, Skopje, performing the role of a strategic centre of the Central Balkan Peninsula, mainly since the 6th until the end of the 19th century. This Fortress served as one of the most important military and administrative sites of the competing military powers of the Middle Ages: Byzantium; the II Bulgarian Kingdom; the King- dom of Samuel and the Serbian Kingdom, when it became the ca- pital of Tsar Dushan, and later the seat of the Ottoman rulers. (a) After the extensive field research conducted in 1967, a major ex- cavation campaign was performed during 2007 within the circum- ference of the mediaeval Skopje Fortress [1]. Among the finds, the most unique discovery of the excavation campaign are the re- mains of a church (Fig. 1.a), located at the hilltop position within the fortification. This is so far the only church unearthed within the walls of the Skopje fortification. The existence of the church is do- cumented in primary literary data from 1573 by the traveler Phi- lippe du Fresne-Canaye. -

1086 € 8 Days 14 Skopje to Dihovo 4 Walking Tours Europe #B1/2391

Full Itinerary and Tour details for 8-day Walking Tour Western Macedonia Level 4 Prices starting from. Trip Duration. Max Passengers. 1086 € 8 days 14 Start and Finish. Activity Level. Skopje to Dihovo 4 Experience. Tour Code. Walking Tours Europe #B1/2391 8-day Walking Tour Western Macedonia Level 4 Tour Details and Description Macedonia remains one of Europe’s last undiscovered areas. Being centrally located in the Balkans, this country is a crossroad between the East and West, Christianity and Islam, melting pot of civilizations, which reflects in its culture and overall way of life even today. During this adventurous journey you will experience firsthand Macedonia’s beautiful nature with walks in the areas of Skopje and the national parks of Mavrovo and Galicica. The tour also includes a day of exploration in the area of Ohrid - Macedonian UNESCO world cultural and natural heritage site. During the journey you will taste local cuisine typical for each area visited prepared by friendly locals, and combine the delicacies with premium Macedonian wines and spirits. Included in the Walking Tour: • Transportation throughout the journey (English speaking driver, fuel, pay tolls, parking incl.) • Experienced tour leader • Accommodation at hotels and family homes (as per program) • All meals (as per program; beverages excluded) at hotels/local restaurants/family homes/outdoor locations • Entrance fees in national parks / archaeological sites • 24/7 assistance Not Included in the tour: • Transfers to Macedonia • Optional meals and activities (boat trips, lunches) • Travel insurance • Tips • Personal expenses Minimum 4 people (ask us for price for 2 or 3 people) Departure dates on request - minimum 4 people Check Availability Book Online Now Send an Enquiry 2/6 8-day Walking Tour Western Macedonia Level 4 Day 2 Walking in the Skopje area (Mt. -

The Panoramic Tour of Skopje

The Panoramic Tour of Skopje 22 April 2017 09:00 Departure from the conference center Professional and experienced licensed guide during the tours. Transportation by a comfortable AC non smoking Luxurious car / Van with professional driver. 20:00 Returning to the hotel Price: FREE During the Tour will visit the Historical Places Macedonia Square Stone Bridge Skopje Fortress Old Bazaar Skopje Ishak Bey Mosque Museum of The Macedonian Struggle (Skopje) Note: Only, the museums entrance fee and lunch will be paid by the participants. Historical Places Information 1. Macedonia Square It is located in the central part of the city, and it crosses the Vardar River. The Christmas festivals are always held there and it commonly serves as the site of cultural, political and other events. The independence of Macedonia from Yugoslavia was declared here by the country's first president, Kiro Gligorov. The square is currently under re- development and there are many new buildings around the square being constructed. The three main streets that merge onto the square are Maksim Gorki, Dimitar Vlahov and Street Macedonia. Dimitar Vlahov Street was converted into a pedestrian street in 2011. Maksim Gorki, while not a pedestrian zone, is lined with Japanese Cherry trees, whose blossoms in spring mark a week-long series of Asian cultural events. Finally, Macedonia Street, the main pedestrian street, connects Macedonia Square to the Old Railway Station (destroyed by the 1963 earthquake), which houses the City of Skopje Museum. Along Macedonia Street is the Mother Teresa Memorial House, which features an exhibit of art facts from Mother Teresa's life. -

T E H N O L a B Ltd Skopje

T E H N O L A B Ltd Skopje Environment, technology, protection at work, nature PO Box.827, Jane Sandanski 113, Skopje tel./fax: ++389 2 2 448 058 / ++389 70 265 992 www. tehnolab.com.mk; e-mail: [email protected] Study on Wastewater Management in Skopje ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (EIA) STUDY FINAL REPORT October, 2008 Skopje Part II: A6-43 Tehnolab Ltd.—Skopje EIA Study WWTP, Skopje Ordered by : Japan International Cooperation Agency Study Team Project : Study on Wastewater Management in Skopje File : EIA Study (Main Report and Annexes) Prepared by : Tehnolab Ltd, Skopje Team leader : M.Sc. Magdalena Trajkovska Trpevska (B.Sc. Chemical engineer) Experts involved : Ph. D. Stanislava Dodeva (B.Sc. Civil Hydro engineer), Environmental expert Ljubomir Ivanovski (B.Sc. Energy engineer) - Environmental expert, cooperator of team leader Andrijana Veljanoska (B.Sc. Environmental engineer) (team leader assistant) Borce Aleksov (B.Sc. Chemical engineer) - Environmental expert, co-operator of team leader Ph.D. Vlado Matevski , Expert Biologist (Expert regarding Flora) Ph. D. Sveto Petkovski, Expert Biologist (Expert regarding Fauna) Ph. D. Branko Micevski, Expert Biologist (Expert regarding endemic Bird species) Ph. D. Jelena Dimitrijevic (B.Sc. Techology engineer), Expert regarding social environmental aspects Date: October 2008 "TEHNOLAB" Ltd Skopje Company for technological and laboratory researches projections and services Manager: M.Sc. Magdalena Trajkovska Trpevska chemical engineer Part II: A6-44 Tehnolab Ltd.—Skopje EIA Study -

T2. COMPETITION PROJECT PROGRAM T.2.1 / Context of The

T2. COMPETITION PROJECT PROGRAM T.2.1 / Context of the competition The Competition for preparation of preliminary urban and architectural development design for arrangement of the Kale Hill in Skopje constitutes an integral part of the project Kale – Cultural Fortress, organized by the Museum of Contemporary Art in Skopje, with the goal of encouraging the revitalization and spatial arrangement of the Kale Hill into an attractive and vibrant city attraction with various cultural, educational and recreational functions. T.2.2/ Current state Two important cultural monuments dominate the Kale Hill: The mediaeval fortress – Kale and the Museum of Contemporary Art in (https://msu.mk/). The exceptional historic and contemporary significance of these two imposing structures for the City of Skopje have been largely diminished due to many years of neglect of the broader location of the Kale Hill. The uncultivated and barely accessible areas of greenery and waste, poorly approachable lighting infrastructure, as well as the many temporary substandard structures divide the Kale Hill into multiple functionally incompatible, isolated and secluded spatial fragments. Feeling the detrimental consequences of this situation regarding the availability to the public on one hand, while being aware of the enormous potential of this space in possible support and expansion of the diversity and attractiveness of our programs on the other hand, the team of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Skopje, by announcing this competition for preliminary design proposals, encourages bold and innovative, but at the same time simple and feasible ideas and concepts for cultivating the Kale Hill into “cultural fortress” and the public interest. -

Program of Government (2017-2020)

PROGRAM OF GOVERNMENT 2017 - 2020 PROGRAM OF GOVERNMENT 2017-2020 Based on the results obtained at the early parliamentary elec- tions held on 11 December 2016, the political parties that won ma- jority seats in the Assembly of the Republic of Macedonia agreed to form parliamentary majority in view of creating the new Govern- ment of the Republic of Macedonia. The political parties give full support for formation of the Gov- ernment of the Republic of Macedonia and mandate it to imple- ment the political commitments enlisted in this PROGRAM OF GOVERNMENT 2017-2020 The parliamentary majority, unequivocally dedicated to strengthening the unitary character, sovereignty and stability of the Republic of Macedonia, declares its unbind- ing political will to establish a reform-oriented government focused on Republic of Macedonia’s common strategic priorities, accession to NATO and the European Union, and secure prompt and sustainable resolution of the political crisis by allowing for true separation of powers, Rule of Law and the establishment of strong and professional institutions. The political parties give full support for formation of the Government of the Re- public of Macedonia which, fully respecting the Constitution of the Republic of Mac- edonia and its international obligations, will dedicate itself to unification of all political forces behind a platform for a European and Euro-Atlantic Republic of Macedonia. The Government’s political priorities will be embedded in the Priebe Report and the urgent reform priorities defined by the European Union. The parliamentary majority will work with dedication on building good interethnic relations based on the principles of mutual respect and tolerance and the implementation of the Ohrid Framework Agreement. -

Beyond Your Dreams Beyondbeyond Your Your Dreams Dreams

Beyond your dreams BeyondBeyond your your dreams dreams DestınatıonDestınatıon MacedonıaIsrael Macedonıa Part Balkan, part Mediterranean and rich in Greek, Roman and Ottoman history, Macedonia has a fascinating past and complex national psyche. Glittering Lake Ohrid and the historic waterside town of Ohrid itself have etched out a place for Macedonia on the tourist map, but this small nation is far more than just one great lake. Skopje may be the Balkans' most bonkers and unfailingly entertaining capital city, thanks to a government- led building spree of monuments, museums and fountains. What has emerged is an intriguing jigsaw where ancient history and buzzing modernity collide. The rest of Macedonia is a stomping ground for adventurers. Tourist infrastructure is scant, but locals are unfailingly helpful. Mountains are omnipresent and walking trails blissfully quiet. The national parks of Mavrovo, Galičica and Pelister are also cultivating some excellent cultural and food tourism initiatives; these gorgeous regions are criminally underexplored. If you want to get off the beaten track in Europe, this is it. Beyond your dreams How to get there? Skopje Alexander The Great International Airport offers daily departures to Austria, Croatia, Germany, Italy, Turkey, Serbia, Switzerland and UK. Many visitors drive from neighboring countries of Albania, Bulgaria, Greece, Kosovo and Serbia. Highways are modern and driving is quite easy. Gas stations and tollbooths are frequent but many offer free Wi-Fi. Only in the countryside, there are not many street signs and places can be hard to find. Even though the people are very friendly, language can be a barrier, especially in villages. -

Study on WINE Tourismin

Study on WINE Tourism in the REPUBLIC OF NORTH MACEDONIA Created by: Working Team from TURISTIKA Skopje: Dejan Metodijeski, Oliver Filiposki, Emilija Todorovic, Milena Taleska, Georgi Michev, Cedomir Dimovski, Nako Taskov, Kristijan Dzambazovski, Nikola Cuculeski, Mladen Micevski. Photos: Under the consent of wineries included in the survey, for the needs of the Study. Design: Stojan Kaevski Proofreading: Tole Belchev Disclaimer: This study has been developed under the 2019 Tourism Development Programme. The opinions and views stated in this publication do not necessarily reflect the opinions and views of the Ministry of Economy of the Republic of North Macedonia CONTENTS FOREWORD .........................................................................................................................................................................................4 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................................................................5 METHODOLOGICAL FRAME OF STUDY DEVELOPMENT ...........................................................................................................7 I. GLOBAL TRENDS IN WINE TOURISM .......................................................................................................................................9 1. Characteristics of wine tourism ..........................................................................................................................................9 -

Here to Expertly Guide You Through the New Normal in Travel

Our Experience At Exeter International we have been creating memories and crafting custom-designed journeys for 27 years. We are a team of specialists committed to providing the best travel experiences in our destinations. Each of our experts has either travelled extensively on reconnaissance trips, or has lived in their area of expertise, giving us unparalleled first-hand knowledge. Because we focus on specific parts of the globe, we return to the same destinations many times, honing our experience over the years. Knowledgeable Up-to-the-Minute Local Information We are best placed to give you advice about traveling to Europe and beyond, from logistics and new protocols in museums, hotels, and restaurants in each country. We are here to expertly guide you through the new normal in travel. Original Custom Programs, Meticulously Planned Our experts speak your language both literally and culturally. Our advice and recommendations are impartial, honest, and always have the individual in mind. We save valuable time in pre-trip research and focus on developing experiences that enrich and enhance your experience. Once on your journey you will have complete peace of mind with our local 24-hour contact person who is on hand to coordinate any changes in your program or help you in the case of any emergency. Hand-Selected Guides We know that guides are one of the most important components of any travel experience. That is why we only use local experts who have a history of working with our guests and whom we know personally. We are extremely particular in selecting our guides and are confident that they will be one of the most memorable aspects of any of our trips. -

1 “Skopje 2014” – Between Belated Nation-Building and the Challenges of Globalisation a Dissertation Submitted in Partial

Skopje 2014 – Between Belated Nation-Building and the Challenges of Globalisation A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of doctor philosophiae to the Department of Political and Social Sciences of Freie Universität Berlin by Zan Ilieski Berlin, 2017 1 Reviewers: Prof. Dr. Manuela Boatca Albert Ludwig University of Freiburg Institute of Sociology Global Studies Programme Prof. Dr. Katharina Bluhm Freie Universität Berlin Department of Political and Social Sciences Institute for East-European Studies Date of defense: 19 July, 2017 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS...............................................................................................................................3 SUMMARY...............................................................................................................................................9 ZUSAMMENFASSUNG............................................................................................................................12 CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION..................................................................................................................16 CHAPTER 2: THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK..............................................................................................27 Research problem..................................................................................................................................27 Democracy – a contested notion...........................................................................................................34 -

Elizabeta Dimitrova, Orhideja Zorova (University of Sts Cyril and Methodius/Ministry of Culture, Skopje)

Ni{ i Vizantija XVII 367 Elizabeta Dimitrova, Orhideja Zorova (University of Sts Cyril and Methodius/Ministry of culture, Skopje) THE PARALEL UNIVERSES OF MACEDONIAN CULTURAL MULTIVERSE In physics‘ string theory, the multiverse is a notion in which our uni- verse is not the only one; on the contrary, many universes exist parallel to each other. These distinct universes within the multiverse theory are called parallel universes1. In other words - a variety of different theories lend themselves to a multiverse viewpoint. On a more general level, this could be sumarized in one of the brilliant quotations by late professor Stephen Hawking, who used to say: There is no unique picture of reality2. What he meant by this sentence is that reality is subjective – which points to the subjective character of experience. On the other hand, we all know that the world is an objective reality and exists independently of us. That would imply that the phrase is also ultimately about the practical human value of the objective reality. In other words, the objective reality, although independant of our existence, is valuable insofar as it can also fit into our subjective perception of reality3. Similarly to physics but on a much greater scale, in modern humanities there are theories that contradict each other with a wide scope of arguments and debate in the pursuit of substantial evidence. History, archaeology and art history are among the disciplines with a variety of such academic contradictions related to some major issues, the resolution of which could bring a different perspective even in our daily lifes.