Migraine Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics and Drug

pharmaceutics Review Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics and Drug–Drug Interactions of New Anti-Migraine Drugs—Lasmiditan, Gepants, and Calcitonin-Gene-Related Peptide (CGRP) Receptor Monoclonal Antibodies Danuta Szkutnik-Fiedler Department of Clinical Pharmacy and Biopharmacy, Pozna´nUniversity of Medical Sciences, Sw.´ Marii Magdaleny 14 St., 61-861 Pozna´n,Poland; [email protected] Received: 28 October 2020; Accepted: 30 November 2020; Published: 3 December 2020 Abstract: In the last few years, there have been significant advances in migraine management and prevention. Lasmiditan, ubrogepant, rimegepant and monoclonal antibodies (erenumab, fremanezumab, galcanezumab, and eptinezumab) are new drugs that were launched on the US pharmaceutical market; some of them also in Europe. This publication reviews the available worldwide references on the safety of these anti-migraine drugs with a focus on the possible drug–drug (DDI) or drug–food interactions. As is known, bioavailability of a drug and, hence, its pharmacological efficacy depend on its pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, which may be altered by drug interactions. This paper discusses the interactions of gepants and lasmiditan with, i.a., serotonergic drugs, CYP3A4 inhibitors, and inducers or breast cancer resistant protein (BCRP) and P-glycoprotein (P-gp) inhibitors. In the case of monoclonal antibodies, the issue of pharmacodynamic interactions related to the modulation of the immune system functions was addressed. It also focuses on the effect of monoclonal antibodies on expression of class Fc gamma receptors (FcγR). Keywords: migraine; lasmiditan; gepants; monoclonal antibodies; drug–drug interactions 1. Introduction Migraine is a chronic neurological disorder characterized by a repetitive, usually unilateral, pulsating headache with attacks typically lasting from 4 to 72 h. -

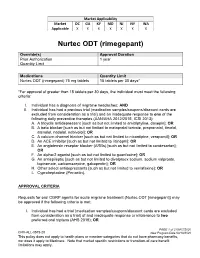

Nurtec ODT (Rimegepant)

Market Applicability Market DC GA KY MD NJ NY WA Applicable X X X X X X X Nurtec ODT (rimegepant) Override(s) Approval Duration Prior Authorization 1 year Quantity Limit Medications Quantity Limit Nurtec ODT (rimegepant) 75 mg tablets 15 tablets per 30 days* *For approval of greater than 15 tablets per 30 days, the individual must meet the following criteria: I. Individual has a diagnosis of migraine headaches; AND II. Individual has had a previous trial (medication samples/coupons/discount cards are excluded from consideration as a trial) and an inadequate response to one of the following daily preventive therapies (AAN/AHA 2012/2015, ICSI 2013): A. A tricyclic antidepressant [such as but not limited to amitriptyline, doxepin]; OR B. A beta blocker [such as but not limited to metoprolol tartrate, propranolol, timolol, atenolol, nadolol, nebivolol]; OR C. A calcium channel blocker [such as but not limited to nicardipine, verapamil]; OR D. An ACE inhibitor [such as but not limited to lisinopril]; OR E. An angiotensin receptor blocker (ARBs) [such as but not limited to candesartan]; OR F. An alpha-2 agonist [such as but not limited to guanfacine]; OR G. An antiepileptic [such as but not limited to divalproex sodium, sodium valproate, topiramate, carbamazepine, gabapentin]; OR H. Other select antidepressants [such as but not limited to venlafaxine]; OR I. Cyproheptadine (Periactin). APPROVAL CRITERIA Requests for oral CGRP agents for acute migraine treatment (Nurtec ODT [rimegepant]) may be approved if the following criteria is met: I. Individual has had a trial (medication samples/coupons/discount cards are excluded from consideration as a trial) of and inadequate response or intolerance to two preferred oral triptans (AHS 2019); OR PAGE 1 of 2 08/07/2020 CRX-ALL-0575-20 New Program Date 03/19/2020 This policy does not apply to health plans or member categories that do not have pharmacy benefits, nor does it apply to Medicare. -

VYEPTI™ (EPTINEZUMAB) Policy Number: CSLA2020D0090A Effective Date: TBD

Proprietary Information of United Healthcare: The information contained in this document is proprietary and the sole property of United HealthCare Services, Inc. Unauthorized copying, use and distribution of this information are strictly prohibited. Copyright 2020 United HealthCare Services, Inc. UnitedHealthcare® Community Plan Medical Benefit Drug Policy VYEPTI™ (EPTINEZUMAB) Policy Number: CSLA2020D0090A Effective Date: TBD Table of Contents Page Commercial Policy APPLICATION ...................................................... 1 Vyepti™ (Eptinezumab) COVERAGE RATIONALE ........................................ 1 APPLICABLE CODES ............................................. 2 BACKGROUND ................................................... 43 CLINICAL EVIDENCE ............................................ 4 U.S. FOOD AND DRUG ADMINISTRATION ............ 54 CENTERS FOR MEDICARE AND MEDICAID SERVICES 54 REFERENCES ....................................................... 5 POLICY HISTORY/REVISION INFORMATION ...... 65 INSTRUCTIONS FOR USE .................................... 65 APPLICATION This Medical Benefit Drug Policy only applies to state of Louisiana. COVERAGE RATIONALE Vyepti has been added to the Review at Launch program. Please reference the Medical Benefit Drug Policy titled Review at Launch for New to Market Medications for additional details. Chronic Migraine Vyepti is proven and medically necessary for the preventive treatment of chronic migraines when all of the following criteria are met: For initial therapy, all of the -

Rimegepant in the Treatment of Migraine

Arch Intern Med Res 2020; 3(2): 119-123 DOI: 10.26502/aimr.0030 Review Article Rimegepant in the Treatment of Migraine Muhammad Adnan Haider1*, Muhammad Hanif2, Mukarram Jamat Ali3, Muhammad Umer Ahmed4, Sundas2, Amin H Karim5 1Department of Internal Medicine, Allama Iqbal Medical College, Lahore, Pakistan 2Department of Internal Medicine, Khyber Medical College Peshawar, Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan 3Department of Internal Medicine, King Edward Medical University Lahore, Lahore, Pakistan 4Department of Internal Medicine, Ziauddin University and hospital, Karachi, Pakistan 5Associate Clinical Professor of Cardiology, Baylor College of medicine, Houston, United States *Corresponding author: Muhammad Adnan Haider, Department of Internal Medicine, Allama Iqbal Medical College, Lahore, Pakistan, E-mail: [email protected] Received: 02 May 2020; Accepted: 18 May 2020; Published: 21 May 2020 Citation: Muhammad Adnan Haider, Muhammad Hanif, Mukarram Jamat Ali, Muhammad Umer Ahmed, Sundas, Amin H Karim. Rimegepant in the Treatment of Migraine. Archives of Internal Medicine Research 3 (2020): 119- 123. Abstract Migraine is a common and chronic disorder with ent of migraine. This article is focused on exploring the significant financial and socioeconomic burden. It is the role of rimegepant (CGRP-receptor antagonist) by 2nd most common reason for the years lived with reviewing myriads of articles published in Pubmed and disability after back pain. Current available treatment of Google scholar. migraine is limited to subpopulation due to poor tolerability, efficacy, side effects, contraindication and Keywords: Rimegepant; CGRP; Triptans; Migraine; drug-drug interactions. So there is need to evolve some Receptor antagonist treatment to overcome these limitations. Calcitonin- gene-related peptide receptor has been identified in the 1. -

CGRP Signaling Via CALCRL Increases Chemotherapy Resistance and Stem Cell Properties in Acute Myeloid Leukemia

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article CGRP Signaling via CALCRL Increases Chemotherapy Resistance and Stem Cell Properties in Acute Myeloid Leukemia 1,2 1,2, 1,2, 1,2 Tobias Gluexam , Alexander M. Grandits y, Angela Schlerka y, Chi Huu Nguyen , Julia Etzler 1,2 , Thomas Finkes 1,2, Michael Fuchs 3, Christoph Scheid 3, Gerwin Heller 1,2 , Hubert Hackl 4 , Nathalie Harrer 5, Heinz Sill 6 , Elisabeth Koller 7 , Dagmar Stoiber 8,9, Wolfgang Sommergruber 10 and Rotraud Wieser 1,2,* 1 Division of Oncology, Department of Medicine I, Medical University of Vienna, Waehringer Guertel 18-20, 1090 Vienna, Austria; [email protected] (T.G.); [email protected] (A.M.G.); [email protected] (A.S.); [email protected] (C.H.N.); [email protected] (J.E.); thomas.fi[email protected] (T.F.); [email protected] (G.H.) 2 Comprehensive Cancer Center, Spitalgasse 23, 1090 Vienna, Austria 3 Department I of Internal Medicine, Center for Integrated Oncology Aachen Bonn Cologne Duesseldorf, University of Cologne, Kerpener Str. 62, 50937 Cologne, Germany; [email protected] (M.F.); [email protected] (C.S.) 4 Institute of Bioinformatics, Biocenter, Medical University of Innsbruck, Innrain 80, 6020 Innsbruck, Austria; [email protected] 5 Department for Cancer Research, Boehringer Ingelheim RCV GmbH & Co KG, Dr. Boehringer-Gasse 5-11, A-1121 Vienna, Austria; [email protected] 6 Division of Hematology, Medical University of Graz, Auenbruggerplatz -

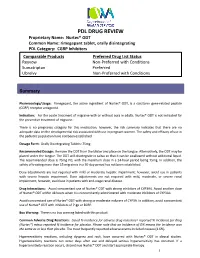

Nurtec® ODT Common Name: Rimegepant Tablet, Orally Disintegrating PDL Category: CGRP Inhibitors

PDL DRUG REVIEW Proprietary Name: Nurtec® ODT Common Name: rimegepant tablet, orally disintegrating PDL Category: CGRP Inhibitors Comparable Products Preferred Drug List Status Reyvow Non‐ Preferred with Conditions Sumatriptan Preferred Ubrelvy Non‐Preferred with Conditions Summary Pharmacology/Usage: Rimegepant, the active ingredient of Nurtec® ODT, is a calcitonin gene‐related peptide (CGRP) receptor antagonist. Indication: For the acute treatment of migraine with or without aura in adults. Nurtec® ODT is not indicated for the preventive treatment of migraine. There is no pregnancy category for this medication; however, the risk summary indicates that there are no adequate data on the developmental risk associated with use in pregnant women. The safety and efficacy of use in the pediatric population have not been established. Dosage Form: Orally Disintegrating Tablets: 75mg Recommended Dosage: Remove the ODT from the blister and place on the tongue. Alternatively, the ODT may be placed under the tongue. The ODT will disintegrate in saliva so that it can be swallowed without additional liquid. The recommended dose is 75mg PO, with the maximum dose in a 24‐hour period being 75mg. In addition, the safety of treating more than 15 migraines in a 30‐day period has not been established. Dose adjustments are not required with mild or moderate hepatic impairment; however, avoid use in patients with severe hepatic impairment. Dose adjustments are not required with mild, moderate, or severe renal impairment; however, avoid use in patients with end‐stage renal disease. Drug Interactions: Avoid concomitant use of Nurtec® ODT with strong inhibitors of CYP3A4. Avoid another dose of Nurtec® ODT within 48 hours when it is concomitantly administered with moderate inhibitors of CYP3A4. -

Comparative Efficacy and Safety of Rimegepant Versus Ubrogepant and Lasmiditan for Acute Poster No

Comparative Efficacy and Safety of Rimegepant Versus Ubrogepant and Lasmiditan for Acute Poster No. P6.002 Treatment of Migraine: A Network Meta-analysis (NMA) 1 1 1 1 2 2 2 2 2 Karissa Johnston, PhD ; Evan Popoff, MSc ; Alison Deighton, BASc ; Parisa Dabirvaziri, MD ; Linda Harris, MPH ; Alexandra Thiry, PhD ; Robert Croop, MD ; Vladimir Coric, MD ; Gilbert L’Italien, PhD 1 Broadstreet Health Economics & Outcomes Research, Vancouver, BC; 2 Biohaven Pharmaceuticals, New Haven, CT Introduction Methods cont. Figure 3. Network Meta-analysis Results for Efficacy (Rimegepant vs Comparators) • Triptans are the current standard of care for the acute treatment of moderate to severe migraine attacks • Efficacy outcomes included sustained pain freedom and sustained pain relief 2-24 hours post-dose • Despite a demonstrated clinical benefit, response to treatment decreases over time, and triptans are • Safety outcomes included somnolence, dizziness, and nausea contraindicated in patients with cardiovascular conditions1 • Results are expressed in terms of risk difference — the incremental proportion of respondents achieving the • Novel agents for acute migraine treatment include the: outcome of interest across treatments – Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP)-receptor agonists rimegepant orally disintegrating tablet (ODT) and ubrogepant oral tablet Results – 5-HT1F receptor agonist lasmiditan • Five randomized placebo-controlled trials contributed data to the network: • The safety and efficacy of these treatments have been investigated independently -

Preferred Drug List

Kansas State Employee ANALGESICS Second Generation cefprozil Health Plan NSAIDs cefuroxime axetil diclofenac sodium delayed-rel Preferred Drug List diflunisal Third Generation etodolac cefdinir 2021 ibuprofen cefixime (SUPRAX) meloxicam nabumetone Erythromycins/Macrolides naproxen sodium tabs azithromycin naproxen tabs clarithromycin oxaprozin clarithromycin ext-rel sulindac erythromycin delayed-rel erythromycin ethylsuccinate NSAIDs, COMBINATIONS erythromycin stearate diclofenac sodium delayed-rel/misoprostol fidaxomicin (DIFICID) Effective 04/01/2021 NSAIDs, TOPICAL Fluoroquinolones diclofenac sodium gel 1% ciprofloxacin For questions or additional information, diclofenac sodium soln levofloxacin access the State of Kansas website at moxifloxacin http://www.kdheks.gov/hcf/sehp or call COX-2 INHIBITORS Penicillins the Kansas State Employees Prescription celecoxib amoxicillin Drug Program at 1-800-294-6324. amoxicillin/clavulanate The Preferred Drug List is subject to change. GOUT amoxicillin/clavulanate ext-rel To locate covered prescriptions online, allopurinol ampicillin access the State of Kansas website at colchicine tabs dicloxacillin http://www.kdheks.gov/hcf/sehp for the probenecid penicillin VK most current drug list. colchicine (MITIGARE) Tetracyclines What is a Preferred Drug List? OPIOID ANALGESICS doxycycline hyclate A Preferred Drug List is a list of safe and buprenorphine transdermal minocycline cost-effective drugs, chosen by a committee codeine/acetaminophen tetracycline of physicians and pharmacists. Drug lists fentanyl -

Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics

Supplementary Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics and Drug-Drug Interactions of New Anti-Migraine Drugs–Lasmiditan, Gepants, and Calcitonin-Gene-Related Peptide (CGRP) Receptor Monoclonal Antibodies Danuta Szkutnik-Fiedler Table S1. Possible drug-drug interactions of lasmiditan [14,28,31,35–38,40,42,45–47]. The risk or severity of Serum concentration of the Serum concentration of Lasmiditan may serotonin syndrome can following drugs (P-gp lasmiditan (P-gp substrate) increase the be potentially increased and/or BCRP substrates) may potentially increase bradycardic when lasmiditan is may potentially increase when it is combined with effects of the combined with the when combined with the following drugs3,. following drugs. following drugs1,. lasmiditan2,. 5-hydroxytryptophan* afatinib acebutolol alfentanil* alpelisib amlodipine almotriptan* ambrisentan atenolol amitriptiline* apixaban betaxolol amoxapine* belinostat carteolol buspirone* bisoprolol carvedilol citalopram* brentuximab vedotin diltiazem clomipramine* cabazitaxel esmolol cyclobenzaprine* ceritinib felodipine desipramine* cladribine isradipine desvenlavaxine* cobimetinib clobazam ivabradine dexfenfluramine* colchicine* daclatasvir labetalol dextromethorphan* cyclosporine erythromycin levobetaxolol dihydroergotamine* daunorubicin fexofenadine levobunolol dolasetron* delafloxacin lapatinib methyldopa doxepin* digitoxin ritonavir metipranolol doxepin topical* digoxin metoprolol duloxetine* donepezil nadolol eletriptan* doxorubicin nebivolol ergotamine* edoxaban* nicardipine escitalopram* -

Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide Receptor (CGRP) Antagonists, Acute

Texas Prior Authorization Program Clinical Criteria Drug/Drug Class Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide Receptor (CGRP) Antagonists (Acute Treatment) Clinical Information Included in this Document Nurtec (Rimegepant) Drugs requiring prior authorization: the list of drugs requiring prior authorization for this clinical criteria Prior authorization criteria logic: a description of how the prior authorization request will be evaluated against the clinical criteria rules Logic diagram: a visual depiction of the clinical criteria logic Supporting tables: a collection of information associated with the steps within the criteria (diagnosis codes, procedure codes, and therapy codes); provided when applicable References: clinical publications and sources relevant to this clinical criteria Note: Click the hyperlink to navigate directly to that section. Ubrelvy (Ubrogepant) Drugs requiring prior authorization: the list of drugs requiring prior authorization for this clinical criteria Prior authorization criteria logic: a description of how the prior authorization request will be evaluated against the clinical criteria rules Logic diagram: a visual depiction of the clinical criteria logic Supporting tables: a collection of information associated with the steps within the criteria (diagnosis codes, procedure codes, and therapy codes); provided when applicable References: clinical publications and sources relevant to this clinical criteria Note: Click the hyperlink to navigate directly to that section. October 28, 2020 Copyright © 2011-2020 Health Information Designs, LLC 1 Revision Notes Initial publication, with changes recommended by the DUR Board included October 28, 2020 Copyright © 2011-2020 Health Information Designs, LLC 2 Texas Prior Authorization Program Clinical Criteria CGRP Antagonists (Acute) Nurtec (Rimegepant) Drugs Requiring Prior Authorization The listed GCNS may not be an indication of TX Medicaid Formulary coverage. -

Anatomical Classification Guidelines V2021 EPHMRA ANATOMICAL CLASSIFICATION GUIDELINES 2021

EPHMRA ANATOMICAL CLASSIFICATION GUIDELINES 2021 Anatomical Classification Guidelines V2021 "The Anatomical Classification of Pharmaceutical Products has been developed and maintained by the European Pharmaceutical Marketing Research Association (EphMRA) and is therefore the intellectual property of this Association. EphMRA's Classification Committee prepares the guidelines for this classification system and takes care for new entries, changes and improvements in consultation with the product's manufacturer. The contents of the Anatomical Classification of Pharmaceutical Products remain the copyright to EphMRA. Permission for use need not be sought and no fee is required. We would appreciate, however, the acknowledgement of EphMRA Copyright in publications etc. Users of this classification system should keep in mind that Pharmaceutical markets can be segmented according to numerous criteria." © EphMRA 2021 Anatomical Classification Guidelines V2021 CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION A ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM 1 B BLOOD AND BLOOD FORMING ORGANS 28 C CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM 36 D DERMATOLOGICALS 51 G GENITO-URINARY SYSTEM AND SEX HORMONES 58 H SYSTEMIC HORMONAL PREPARATIONS (EXCLUDING SEX HORMONES) 68 J GENERAL ANTI-INFECTIVES SYSTEMIC 72 K HOSPITAL SOLUTIONS 88 L ANTINEOPLASTIC AND IMMUNOMODULATING AGENTS 96 M MUSCULO-SKELETAL SYSTEM 106 N NERVOUS SYSTEM 111 P PARASITOLOGY 122 R RESPIRATORY SYSTEM 124 S SENSORY ORGANS 136 T DIAGNOSTIC AGENTS 143 V VARIOUS 145 Anatomical Classification Guidelines V2021 INTRODUCTION The Anatomical Classification was initiated in 1971 by EphMRA. It has been developed jointly by Intellus/PBIRG and EphMRA. It is a subjective method of grouping certain pharmaceutical products and does not represent any particular market, as would be the case with any other classification system. -

2020 Aetna Standard Plan

Plan for your best health Aetna Standard Plan Aetna.com Aetna is the brand name used for products and services provided by one or more of the Aetna group of subsidiary companies, including Aetna Life Insurance Company and its affiliates (Aetna). Aetna Pharmacy Management refers to an internal business unit of Aetna Health Management, LLC. Aetna Pharmacy Management administers, but does not offer, insure or otherwise underwrite the prescription drug benefits portion of your health plan and has no financial responsibility therefor. 2020 Pharmacy Drug Guide - Aetna Standard Plan Table of Contents INFORMATIONAL SECTION..................................................................................................................6 *ADHD/ANTI-NARCOLEPSY/ANTI-OBESITY/ANOREXIANTS* - DRUGS FOR THE NERVOUS SYSTEM.................................................................................................................................16 *ALLERGENIC EXTRACTS/BIOLOGICALS MISC* - BIOLOGICAL AGENTS...............................18 *ALTERNATIVE MEDICINES* - VITAMINS AND MINERALS....................................................... 19 *AMEBICIDES* - DRUGS FOR INFECTIONS.....................................................................................19 *AMINOGLYCOSIDES* - DRUGS FOR INFECTIONS.......................................................................19 *ANALGESICS - ANTI-INFLAMMATORY* - DRUGS FOR PAIN AND FEVER............................19 *ANALGESICS - NONNARCOTIC* - DRUGS FOR PAIN AND FEVER.........................................