Download Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Initiating, Planning and Managing Coalitions

INITIATING, PLANNING AND MANAGING COALITIONS AN AFRICAN LIBERAL PERSPECTIVE HANDBOOK INITIATING, PLANNING AND MANAGING COALITIONS CONTRIBUTORS Gilles Bassindikila Justin Nzoloufoua Lucrèce Nguedi Leon Schreiber Solly Msimanga Helen Zille Lotfi Amine Hachemi Assoumane Kamal Soulé Madonna Kumbu Kumbel Serge Mvukulu Bweya-Nkiama Tolerance Itumeleng Lucky Daniel Tshireletso Maître Boutaina Benmallam Richard Nii Amarh Nana Ofori Owusu Mutale Nalumango Dr Choolwe Beyani PUBLICATION COORDINATOR Nangamso Kwinana TRANSLATION Mathieu Burnier & Marvin Mncwabe at LoluLwazi Business Support DESIGN Vernon Kallis at LoluLwazi Business Support EDITORS Iain Gill Gijs Houben Martine Van Schoor Daniëlle Brouwer Masechaba Mdaka Nangamso Kwinana For further information and distribution Africa Liberal Network 3rd Floor Travel House, 6 Hood Avenue Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196 The Republic of South Africa Direct: +27 87 806 2676 Telephone: +27 11 880 8851 Mobile: +27 73 707 8513 CONTRIBUTORS [email protected] www.africaliberalnetwork.org 2 3 INITIATING, PLANNING AND MANAGING COALITIONS AN AFRICAN LIBERAL PERSPECTIVE HANDBOOK A Word from our President 4 CONTENTS 5 Our Executive Committee 7 About the Author 8 Introduction 10 Methodology 12 Foreward 15 In Memoriam 16 Initiating - The Pre-Election Phase 30 Planning - Pre-Coalition Phase 38 Managing - The Governing Phase 3 INITIATING, PLANNING AND MANAGING COALITIONS Dear reader, We are delighted and proud to share with you, this publication relating to initiating, planning and managing coalitions. -

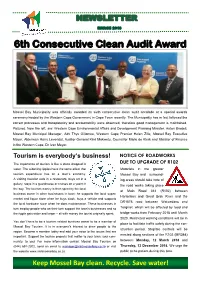

6Th Consecutive Clean Audit Award

MARCH 2018 6th Consecutive Clean Audit Award Mossel Bay Municipality was officially awarded its sixth consecutive clean audit accolade at a special awards ceremony hosted by the Western Cape Government in Cape Town recently. The Municipality has in fact followed the correct processes and transparency and accountability were observed, therefore good management is maintained. Pictured, from the left, are: Western Cape Environmental Affairs and Development Planning Minister, Anton Bredell, Mossel Bay Municipal Manager, Adv Thys Giliomee, Western Cape Premier Helen Zille, Mossel Bay Executive Mayor, Alderman Harry Levendal, Auditor-General Kimi Makwetu, Councillor Marie de Klerk and Minister of Finance in the Western Cape, Dr Ivan Meyer. Tourism is everybody’s business! NOTICE OF ROADWORKS The importance of tourism is like a stone dropped in DUE TO UPGRADE OF R102 water. The widening ripples have the same effect that Motorists in the greater tourism expenditure has on a town’s economy. Mossel Bay and surround- A visiting traveller eats in a restaurant, buys art in a ing areas should take note of gallery, stays in a guesthouse or cruises on a yacht in the road works taking place the bay. The tourism money is then spent by the local at Main Road 344 (R102) between business owner in other businesses in town: he supports the local super- Hartenbos and Great Brak River and the market and liquor store when he buys stock, buys a vehicle and supports DR1578 road between Wolwedans and the local hardware store when he does maintenance. These businesses in turn employ people who on their turn support the town’s businesses and so Tergniet, which will be affected by road and the ripple gets wider and larger – all with money the tourist originally spent. -

Colin Eglin, the Progressive Federal Party and the Leadership of the Official Parliamentary Opposition, 1977‑1979 and 1986‑1987

Journal for Contemporary History 40(1) / Joernaal vir Eietydse Geskiedenis 40(1): 1‑22 © UV/UFS • ISSN 0285‑2422 “ONE OF THE ARCHITECTS OF OUR DEMOCRACY”: COLIN EGLIN, THE PROGRESSIVE FEDERAL PARTY AND THE LEADERSHIP OF THE OFFICIAL PARLIAMENTARY OPPOSITION, 1977‑1979 AND 1986‑1987 FA Mouton1 Abstract The political career of Colin Eglin, leader of the Progressive Federal Party (PFP) and the official parliamentary opposition between 1977‑1979 and 1986‑1987, is proof that personality matters in politics and can make a difference. Without his driving will and dogged commitment to the principles of liberalism, especially his willingness to fight on when all seemed lost for liberalism in the apartheid state, the Progressive Party would have floundered. He led the Progressives out of the political wilderness in 1974, turned the PFP into the official opposition in 1977, and picked up the pieces after Frederik van Zyl Slabbert’s dramatic resignation as party leader in February 1986. As leader of the parliamentary opposition, despite the hounding of the National Party, he kept liberal democratic values alive, especially the ideal of incremental political change. Nelson Mandela described him as, “one of the architects of our democracy”. Keywords: Colin Eglin; Progressive Party; Progressive Federal Party; liberalism; apartheid; National Party; Frederik van Zyl Slabbert; leader of the official parliamentary opposition. Sleutelwoorde: Colin Eglin; Progressiewe Party; Progressiewe Federale Party; liberalisme; apartheid; Nasionale Party; Frederik van Zyl Slabbert; leier van die amptelike parlementêre opposisie. 1. INTRODUCTION The National Party (NP) dominated parliamentary politics in the apartheid state as it convinced the majority of the white electorate that apartheid, despite the destruction of the rule of law, was a just and moral policy – a final solution for the racial situation in the country. -

Structural Barriers to Treatment for Pregnant Coloured Women Abusing TIK in Cape Town: the Experiences of Healthcare Providers

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Stellenbosch University SUNScholar Repository Structural barriers to treatment for pregnant Coloured women abusing TIK in Cape Town: The experiences of healthcare providers by Jodi Bronwyn Nagel Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts and Social Sciences (Psychology) at Stellenbosch University. Supervisor: Dr Chrisma Pretorius March 2017 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za i STRUCTURAL BARRIERS TO TREATMENT Declaration By electronically submitting this thesis, I declare that content therein, it its entirety, is my own, original work and that I have full authorship and ownership thereof. I have not previously submitted this work, in part or in entirety, for the obtaining of any qualification. March 2017 Signature Date Copyright © 2017 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za ii STRUCTURAL BARRIERS TO TREATMENT Abstract Despite interventions that aim to address the barriers to healthcare treatment for pregnant Coloured women abusing TIK in Cape Town, the rate of accessing substance abuse treatment and maternal care amongst this population remains dismally low. Recent literature has given attention to highlighting the structural barriers to treatment as experienced from the perspective of pregnant Coloured women; however, little, if any, research has been conducted on these barriers from the healthcare providers’ perspective. The present study thus aimed to identify the structural treatment barriers experienced by healthcare providers who treat pregnant Coloured women who abuse TIK. An exploratory qualitative design was utilised whereby 20 healthcare providers were identified through purposive sampling and subsequently interviewed. -

Ms Helen Zille Premier Mr Dan Plato MEC of Community Safety Cc

25 August 2016 Att: Ms Helen Zille Premier Mr Dan Plato MEC of Community Safety Cc: Ms Debbie Schäfer MEC for Education Prof. Nomafrench Mbombo MEC of Health Mr Albert Fritz MEC for Social Development Ms Anroux Marais MEC of Cultural Affairs and Sport YOUTH DEMAND A SAFE ENVIRONMENT CONDUCIVE TO LEARNING AND DEVELOPMENT MEMORANDUM FROM THE SOCIAL JUSTICE COALITION AND EQUAL EDUCATION 1. The rights to life, dignity, equality and freedom, including freedom from all forms of violence, underpinned the original complaints by our organisations and others that led to the convening of the Khayelitsha Commission of Inquiry (the Commission). 2. As we mark its second anniversary we admit to our anger and frustration at the inaction from all levels of government to take forward the Commission’s recommendations. 3. The Commission’s report released on 25 August 2014 was aimed at improving safety and policing in Khayelitsha, the Western Cape and South Africa. The burden of crime faced by some of the most vulnerable people in our communities and the inefficiencies of the South African Police Service (SAPS) were at the core of the Commission’s work. In addition, the absence of safety because of criminal violence and inadequate social service provision has meant that people cannot access safe schooling, sanitation, transport, clinics and other constitutionally protected services. 4. We acknowledge that the majority of the Commission’s recommendations have been directed at the SAPS - a national function. Some recommendations however require proactive steps to be taken by the Western Cape Government (WCG). Recommendation 12 – A Multi-Sectoral Task Team on Youth Gangs 5. -

Helen Zille and the Struggle for Liberation

POLITICS © TNA ManufaCTURING FONG-KONG HISTORY Helen Zille and the Struggle for Liberation Zille’s distortions are founded on a theory conveniently crafted to inflate the importance of the DA and exaggerate the contribution of conservative liberals to the struggle for freedom. By Eddy Maloka he public anger over the abuse She cited what the PP’s first leader, lines of the Freedom Charter: “We, of history by the Democratic Jan Steytler, once said in 1959: “In the People of South Africa, declare for TAlliance (DA) is expected. But future, colour and colour alone should all our country and the world to know DA leader Helen Zille has been in the not be the yardstick by which people that South Africa belongs to all who business of manufacturing fong-kong are judged”; and made a startling claim: live in it, black and white, and that no history of the struggle for some time; “In the iron grip of apartheid, this was government can justly claim authority it’s only that she has gotten away with radical, subversive even, coming from unless it is based on the will of all the this in the past. An example is her a white South African. In fact, today we people”. speech delivered in November 2009 at look back on Jan Steytler's words and Furthermore, what Zille failed a function to commemorate the 50th realise that he was more than 50 years to mention about the PP is that it anniversary of the Progressive Party ahead of his time”. represented a conservative brand of (PP) which is full of distortions and in This is not true. -

Adjusted Estimates of Provincial Revenue and Expenditure Speech

Western Cape Government 2018 Medium Term Budget Policy Statement and 2018 Adjusted Estimates of Provincial Revenue and Expenditure Speech Dr Ivan Meyer Minister of Finance 22 November 2018 Provincial Treasury Business Information and Data Management Private Bag X9165 7 Wale Street Cape Town tel: +27 21 483 5618 fax: +27 21 483 6601 www.westerncape.gov.za Afrikaans and isiXhosa versions of this publication are available on request. Email: [email protected] 2018 Medium Term Budget Policy Statement and 2018 Adjusted Estimates of Provincial Revenue and Expenditure Speech Honourable Speaker and Deputy Speaker Honourable Premier and Cabinet Colleagues Honourable Leader of the Official Opposition Honourable Leaders of Opposition Parties Honourable Members of the Western Cape Legislature Senior officials of the Western Cape Government Citizens of the Western Cape Special Guests Ladies and Gentlemen Madam Speaker, I rise to today to table the Western Cape Government’s 2018 Medium Term Budget Policy Statement and the 2018 Western Cape Adjusted Estimates of Provincial expenditure in this House. The 2018 WC MTBPS, Madam Speaker, reconfirms the Western Cape Government’s commitment to service delivery and citizen impact. Madam Speaker, over the last ten years this government has invested a lot in institutionalising good governance practices. These are important governance frameworks that allow the Western Cape to serve the citizens for maximum impact. 1 2018 Medium Term Budget Policy Statement and 2018 Adjusted Estimates of Provincial Revenue and Expenditure Speech Just yesterday, Madam Speaker, the Auditor General of South Africa, Kimi Makwetu, announced in the National Parliament that the Western Cape Government has received the best audit outcomes for the 2017/18 financial year. -

Speech by Helen Zille Premier of the Western Cape State

SPEECH BY HELEN ZILLE PREMIER OF THE WESTERN CAPE STATE OF THE PROVINCE ADDRESS WESTERN CAPE PROVINCIAL LEGISLATURE 18 February 2011 10h00 Honourable Speaker Cabinet colleagues The Honourable Leader of the Opposition Members of the diplomatic corps Leaders of political parties Honourable members of the national and provincial parliaments Leaders of local government Director-General and Heads of Department Religious leaders Community leaders Colleagues and friends Citizens of the Western Cape Namkelekile Nonke. Baie welkom aan almal hier vandag It is always a profound honour to make this opening speech of the parliamentary session. Each one of us was elected to represent all the people of our province, and we embrace this responsibility with dedication and humility. This House is the place where government is called upon to account for its actions, where every bill is debated and where the money we spend is scrutinised. The often heated exchanges to which we have grown accustomed are generally a good thing. It shows that our democracy is robust; that there is space for differences and disagreements. And, as our democracy matures, it is essential to ensure that the debate in this House focuses on alternative solutions. We cannot build a shared future if we remain trapped in the conflicts of the past. Of course, the legacy of our tragic past is still with us, and will be for years ahead. This government is committed to redressing that legacy in the shortest possible time by the most sustainable means. Let us therefore accept each other‟s good faith. Let us move away from gratuitous insults and racial posturing. -

Representation of South African Women in the Public Sphere

REPRESENTATION OF SOUTH AFRICAN WOMEN IN THE PUBLIC SPHERE PREPARED BY ADITI HUNMA, RESEARCH ASSISTANT 1 REPRESENTATION OF SOUTH AFRICAN WOMEN IN THE PUBLIC SPHERE METHODOLOGY The aim of this report is to explore how South African women are (re)presented by the media as they engage in the public sphere. It looks at women in three different fields namely, politics, business and art, analysing at the onset the way they argue, that is, as rhetorical agents. It ihen proceeds to assess how these women's gender is perceived to enhance or be detrimental to their capacity to deliver. In the process, the report comes to belie and confront various myths that still persist and taint women's image in the public arena. In the realm of politics, I will be analysing Cape Town Mayor and Head of DA, Helen Zille. In the corporate world, I will be looking at Bulelwa Qupe, who owns the Ezabantu, long-line Hake fishing company, and in the Arts, I will be looking at articles published on Nadine Gordimer, the author who bagged the Nobel Literature Prize less than two decades back. Data for this purpose was compiled from various websites, namely SABCNews.com, Mail and Guardian, News24, IOL and a few blog sites. It was then perused, sorted and labelled. Common topos were extracted and portions dealing with the (re)presentation of women were summarised prior to the actual write up. In the course of the research, I realised that the framing of events had a momentous bearing on the way the women came to be appear and so, I paid close attention to titles, captions and emboldened writings. -

Love Knysna Petition To: Committee Petitions & Executive Undertakings Subject: Response to Knysna Municipality 'S 18 July 2017 Submission (September 11 2017)

LOVE KNYSNA PETITION TO: COMMITTEE PETITIONS & EXECUTIVE UNDERTAKINGS SUBJECT: RESPONSE TO KNYSNA MUNICIPALITY 'S 18 JULY 2017 SUBMISSION (SEPTEMBER 11 2017) To Committee Members The July 18 response by Knysna Municipality to the Committee Petitions & Executive Undertakings is frightening, a continuation of the attempt to discredit me whilst distorting facts, lying and dodging. It begs a detailed response but it would be inconvenient for me to further burden the Committee when it already has sufficient evidence before it in order to clearly make a decision in my favour this Wednesday. Consequently, I request that you only note a few points from me but give consideration to the evidence witness Susan Campbell sent to you this morning, It shows that Knysna Municipality has again misled this Committee, disgracefully using the Great Knysna Fire disaster as an excuse that's in fact lie: • [R0a] Email from witness Susan Campbell. • [R0b] Response from Campbell to Knysna Municipality's July submission. • [R0c] Knysna Tourism (now acting as Knysna & Partners) is illegally funded and in contravention of a host of other laws. That's the legal opinion of outside attorneys hired by the Municipality. Note that I became an activist because of the illegal funding, non-tendering and cronyism of the organisation. My 6 and a half year battle for justice is vindicated by this report BUT the report was ignored and Tourism was recently funded for another year. I cannot confirm but Love Knysna Petition: Hampton's response to Knysna Municipality's July 18 2017 Submission 1 a source told me that Knysna Municipality was instructed by MEC Alan Winde to do so. -

Western Cape Government Provincial Treasury

Western Cape Government Provincial Treasury BUDGET 2017 SPEECH Minister of Finance Dr IH Meyer 7 March 2017 Budget Speech 2017 Western Cape Government Honourable Speaker and Deputy Speaker Honourable Premier and Cabinet Colleagues Honourable Leader of the Official Opposition Honourable Leaders of Opposition Parties Honourable Members of the Western Cape Legislature Executive Mayors and Deputy Mayors Speakers and Councillors Senior officials of the Western Cape Government Leaders of the Business Community Citizens of the Western Cape Ladies and Gentlemen Honourable Speaker, it is my honour to table the Western Cape Government’s 2017 Budget. Two weeks ago Premier Helen Zille defined the Western Cape Government’s vision and clear plans to deliver on that vision. Her State of the Province Address gave a detailed account of what was already achieved during the mid-term assessment. It also puts a razor sharp focus on this Government’s plans, projects and time frames for the future. Today, I am presenting the fiscal framework to fund these plans and projects as outlined in this Government’s delivery Agenda. 1 Budget Speech 2017 Western Cape Government Today I am tabling: A Budget for Growth; A Budget for People; and A Budget for Prosperity. Madam Speaker, there is consensus in this Government and in this Cabinet that nothing is more important than growing the economy and creating jobs. This Budget will support growth and job creation. Madam Speaker, nations prosper when they: Show respect for their Constitution and institutions that support constitutional democracy; Show respect for individual freedom, individual choices, and accept individual responsibility for their own future; Accelerate investment in infrastructure; Boost support for small, medium and micro enterprises; Create jobs and reduce unemployment; Promote smart and inclusive growth; and Have access to basic services like water, energy, sanitation and refuse collection. -

The Challenges of Transitioning from Opposition to Governing Party: the Case Study of the Democratic Alliance in South Africa'

The challenges of transitioning from opposition to governing party: The case study of the Democratic Alliance in South Africa’s Western Cape Province. Sandile Mnikati (214582906) This Dissertation is submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Social Science in Political Science at the School of Social Sciences, College of Humanities, University of KwaZulu-Natal Supervisor: Dr. Khondlo Mtshali Co-supervisor: Mr Sandile Mnguni i DECLARATION I Sandile Mnikati declare that: 1. The research reported in this thesis, except where otherwise indicated,is my original research. 2. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or examination at any other university. 3. This thesis does not contain other persons· data, pictures, graphs or other infom1ation, unless specifically acknowledged asbeing sourced from other persons. 4. This thesis does not contain another persons' writing, unless specifically acknowledged as being sourced from other researchers. \1/hereother written sources have been quoted, then: a. Their words have been re-written, but the general information attributed to them has been referenced b. Where their exact words have been used, then their writing has been placed in inside quotation marks and referenced. 5. This thesis does not contain text, graphicsor tables copied and pasted from the Internet. unless specifically acknowledged, and the source being detailed in the Thesis and in rhe References sections. _Mnikati.S_ Student Name Sign,Ullre. , % Date 2020/05/09 Mtshali, K Supervisor Mnguni.S Co-Supervisor ii Dedication I dedicate this dissertation to all the members of the Mnikathi and Wallett family, you have been a pillar of strength throughout this journey.