Archaeological Investigations at 103—106 Shoreditch High Street, Hackney

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Igniting Change and Building on the Spirit of Dalston As One of the Most Fashionable Postcodes in London. Stunning New A1, A3

Stunning new A1, A3 & A4 units to let 625sq.ft. - 8,000sq.ft. Igniting change and building on the spirit of Dalston as one of the most fashionable postcodes in london. Dalston is transforming and igniting change Widely regarded as one of the most fashionable postcodes in Britain, Dalston is an area identified in the London Plan as one of 35 major centres in Greater London. It is located directly north of Shoreditch and Haggerston, with Hackney Central North located approximately 1 mile to the east. The area has benefited over recent years from the arrival a young and affluent residential population, which joins an already diverse local catchment. , 15Sq.ft of A1, A3000+ & A4 commercial units Located in the heart of Dalston and along the prime retail pitch of Kingsland High Street is this exciting mixed use development, comprising over 15,000 sq ft of C O retail and leisure space at ground floor level across two sites. N N E C T There are excellent public transport links with Dalston Kingsland and Dalston Junction Overground stations in close F A proximity together with numerous bus routes. S H O I N A B L E Dalston has benefitted from considerable investment Stoke Newington in recent years. Additional Brighton regeneration projects taking Road Hackney Downs place in the immediate Highbury vicinity include the newly Dalston Hackney Central Stoke Newington Road Newington Stoke completed Dalston Square Belgrade 2 residential scheme (Barratt Road Haggerston London fields Homes) which comprises over 550 new homes, a new Barrett’s Grove 8 Regents Canal community Library and W O R Hoxton 3 9 10 commercial and retail units. -

Queen of Hoxton Pro Sound� News Europe Online� � � FEBRU�ARY 2011 - Shoreditch

Queen of Hoxton Pro Sound News Europe online FEBRUARY 2011 - Shoreditch On the whole, 2010 could be looked at as a pretty torrid time to be a self-contained music venue in the capital. The future remains uncertain to say the least for its legendary 100 Club; and at the back end of last year, The Luminaire shut its doors for the last time. But it’s not all doom and gloom, apparently. One venue that has kept London’s live music flag flying – well, at half mast, at least - is the Queen of Hoxton – which, actually, is located on Curtain Road in Shoreditch, and has been subject to a major audio overhaul. The venue opened two years ago, but things really started to take off in Summer 2010 when Roots Manuva was first to perform through the 200-capacity venue’s newly installed Funktion-One PA system. Since then, it has accommodated an array of popular bands and DJs including The Maccabees, Rob da Bank and Mat Horne; and a massive show from The Drums at the end of last year. “The response from artists about the new sound system has been phenomenal,” says the Queen’s Danny Payne, “Word has spread, and it’s been integral in attracting bigger acts to play at the venue.” The Funktion-One installation was undertaken by London headquartered Sound Services Ltd, and the main rig consists of a pair of Res 2s and a pair of F-218 subwoofers, along with FFA amplification and Funktion-One- badged XTA processing. Along with its state-of-the-art PA system, the venue now boasts a state-of-the-art Green Room as well, which is a dedicated area located at back-of-house with private dressing rooms and make-up facilities, an all important mini-bar, and a live video link to the main stage that can accommodate up to twenty people in privacy.. -

Cherrymancherryman

GROUND FLOOR PREMISES TO LET – 966 SQ.FT (89.74 SQ.M) GUN COURT, 70 WAPPING LANE, LONDON, E1W 2RD CherrymanCherryman Description Planning The unit is situated on the ground floor with direct The unit currently holds planning for office (B1) use. access to the street. The unit is currently configured for office use in predominantly open plan with a Other retail uses such as a café (A3), medical/day care (D1) or estate agency (A2) could be considered subject to obtaining all necessary consents. partitioned room to house IT equipment. There is a separate WC and tea point/sink area. Energy Performance Certificate Floor Sq. M Sq. Ft The property has an EPC score of 108 (“E” rated). Details available upon Ground 89.74 966 request. Amenities Air-cooling Suspended ceiling Electric heating Perimeter trunking Tea point/sink One parking space WC Self-contained Location Outgoings Gun Court is located on Wapping Lane within one mile of Rent Business Rates Service charge the City of London and two miles from Canary Wharf. Wapping Overground station is within one minute walk £28,980 p.a £5,990.25 p.a £1,168 p.a from the property with direct connection to Canada Water (£30/sq.ft) (£6.20/sq.ft) (£1.20/sq.ft) (Jubilee Line) along with Whitechapel and Shoreditch to the north and Clapham Junction, and Croydon to the south. VAT The building is located close to the restaurants, cafes and This property is elected for VAT pubs Wapping has to offer from established outlets with Contact new units proposed in new developments in the area Lease Term including the large scale redevelopment of the News Colin Leslie [email protected] International site to the north and 22 Wapping Lane. -

Shoreditch E1 01–02 the Building

168 SHOREDITCH HIGH ST. SHOREDITCH E1 01–02 THE BUILDING 168 Shoreditch High Street offers up to 35,819 sq ft of contemporary workspace over six floors in Shoreditch’s most sought after location. High quality architectural materials are used throughout, including linear handmade bricks and black powder coated windows. Whilst the top two floors use curtain walling with black vertical fins – altogether a dramatic first impression for visitors on arrival. The interior is designed with dynamic businesses in mind – providing a stunning, light environment in which to work and create. STELLAR WORK SPACE 03–04 SHOREDITCH Shoreditch is still the undisputed home of the creative and tech industries – but has in recent years attracted other business sectors who crave the vibrant local environment, diverse amenity offering and entrepreneurial spirit. ORIGINALS ARTISTS VISIONARIES HOXTON Crondall St. d. Rd R st nd . Ea la s ng Ki xton St Ho . 05–06 SHOREDITCH Columbia Rd St Hoxton Sq. Rd 6 y d. R Pitfield ckne t s Ha Ea k Pl. Brunswic City 5 R d. 5 Cu St. d r Ol ta Calv et Ave i . 4 n Rivington Rd. Rd WALK TIMES . Arnold Circus. 3 11 OLD ST. 8 8 4 3 6 5 12 SHOREDITCH HIGH ST. STATION 7 MINS Shor 03 9 Gr 168 edit Leonard St. eat 1 10 1 E New Yard Inn. ch High . aste 4 6 7 11 2 Rd 2 10 h St. OLD SPITALFIELD MARKET . 2 churc een t rn 3 Red 4 MINS . 1 9 S St 9 07 8 . -

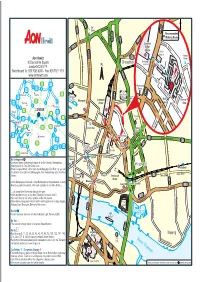

Aon Hewitt-10 Devonshire Square-London EC2M Col

A501 B101 Old C eet u Street Str r t A1202 A10 ld a O S i n Recommended h o A10 R r Walking Route e o d et G a tre i r d ld S e t A1209 M O a c Liverpool iddle t h sex Ea S H d Street A5201 st a tre e i o A501 g e rn R Station t h n S ee Police tr S Gr Station B e e t nal Strype u t Beth B134 Aon Hewitt C n Street i t h C y Bishopsgate e i l i t N 10 Devonshire Square l t Shoreditch R a e P y East Exit w R N L o iv t Shoreditcher g S St o Ra p s t London EC2M 4YP S oo re pe w d l o e y C S p t tr h S a tr o i A1202 e t g Switchboard Tel: 020 7086 8000 - Fax: 020 7621 1511 d i e h M y t s H i D i R d www.aonhewitt.com B134 ev h B d o on c s Main l a h e t i i r d e R Courtyard s J21 d ow e e x A10 r W Courtyard M11 S J23 B100 o Wormwood Devonshire Sq t Chis h e r M25 J25 we C c e l S J27 l Str Street a e M1 eet o l t Old m P Watford Barnet A12 Spitalfields m A10 M25 Barbican e B A10 Market w r r o c C i Main r Centre Liverpool c a r Harrow Pl A406 J28 Moorgate i m a k a e t o M40 J4 t ld S m Gates C Harrow hfie l H Gate Street rus L i u a B le t a H l J1 g S e J16 r o J1 Romford n t r o e r u S e n tr A40 LONDON o e d e M25 t s e Slough M t A13 S d t it r c A1211 e Toynbee h J15 A13 e M4 J1 t Hall Be J30 y v Heathrow Lond ar is on W M M P all e xe Staines A316 A205 A2 Dartford t t a London Wall a Aldgate S A r g k J1 J2 s East s J12 Kingston t p Gr S o St M3 esh h h J3 am d s Houndsditch ig Croydon Str a i l H eet o B e e A13 r x p t Commercial Road M25 M20 a ee C A13 B A P h r A3 c St a A23 n t y W m L S r n J10 C edldle a e B134 M20 Bank of e a h o J9 M26 J3 heap adn Aldgate a m sid re The Br n J5 e England Th M a n S t Gherkin A10 t S S A3 Leatherhead J7 M25 A21 r t e t r e e DLR Mansion S Cornhill Leadenhall S M e t treet t House h R By Underground in M c o Bank S r o a a Liverpool Street underground station is on the Central, Metropolitan, u t r n r d DLR h i e e s Whitechapel c Hammersmith & City and Circle Lines. -

861 Sq Ft Headquarters Office Building Your Own Front Door

861 SQ FT HEADQUARTERS OFFICE BUILDING YOUR OWN FRONT DOOR This quite unique property forms part of the building known as Rotherwick House. The Curve comprises a self-contained building, part of which is Grade II Listed, which has been comprehensively refurbished to provide bright contemporary Grade A office space. The property — located immediately to the east of St Katharine’s Dock and adjoining Thomas More Square — benefits from the immediate area which boasts a wide variety of retail and restaurant facilities. SPECIFICATION • Self-contained building • Generous floor to ceiling heights • New fashionable refurbishment • Full-height windows • New air conditioning • Two entrances • Floor boxes • Grade II Listed building • LG7 lighting with indirect LED up-lighting • Fire and security system G R E A ET T THE TEA TRE E D S A BUILDING OL S T E R SHOREDITCH N S HOUSE OLD STREET T R E E T BOX PARK AD L RO NWEL SHOREDITCH CLERKE C I HIGH STREET T Y R G O O A S D W S F H A O E R L U A L R T AD T H I O R T R N A S STEPNEY D’ O O M AL G B N A GREEN P O D E D T H G O T O WHITECHAPEL A N N R R R O D BARBICAN W O CHANCERY E A FARRINGDON T N O LANE D T T E N H A E M C T N O C LBOR A D O HO M A IGH MOORGATE G B O H S R R U TOTTENHAM M L R LIVERPOOL P IC PE T LO E COURT ROAD NDON WA O K A LL R N R H STREET H C L C E E O S A I SPITALFIELDS I IT A A W B N H D L E W STE S R PNEY WAY T O J R U SALESFORCE A E HOLBORN B T D REE TOWER E ST N I D L XFOR E G T O W R E K G ES H ALDGATE I A H E N TE A O M LONDON MET. -

Opportunities

Thomas More opportunities Square An early opportunity to participate in the transformation of Thomas More Square Thomas More Square Rubbing shoulders with the luxury yachts and ocean going cruisers berthed in St Katharine Docks, Thomas More Square is the perfect opportunity to be part of a business village well adapted for today’s key occupiers, and the next generation’s high tech business suppliers. 1 7 8 9 13 12 Thomas 3 10 More 11 15 16 Square 6 River Thames 4 2 1 5 More central 14 1 Canary Wharf 2 Wapping Station 3 Shadwell Station 4 St Katharine Docks 5 Butler’s Wharf 6 Tower of London 7 Shoreditch High Street Station 8 Spitalfields 9 Liverpool Street Station 10 Bank Station 11 Lloyd’s of London 12 Aldgate Station 13 Aldgate East Station 14 London Bridge Station 15 Tower Hill Station 16 Tower Gateway Station 2 3 More to offer View West Butler’s Wharf St Katharine Docks Tower Bridge The Shard London Eye Tower of London 20 Fenchurch Street Lloyd’s 30 St Mary Axe Heron Tower Broadgate Tower Battersea The Leadenhall Power Station Westminster Building 7 8 9 13 12 Thomas 3 10 More 11 15 16 Square 6 River Thames 4 2 1 5 central 14 1 Canary Wharf 2 Wapping Station 3 Shadwell Station 4 St Katharine Docks 5 Butler’s Wharf 6 Tower of London 7 Shoreditch High Street Station 8 Spitalfields 9 Liverpool Street Station 10 Bank Station 11 Lloyd’s of London 12 Aldgate Station 13 Aldgate East Station 14 London Bridge Station 15 Tower Hill Station 16 Tower Gateway Station 3 1 2 3 More to explore Amenities & Neighbours The Thomas More Square development provides you 4 with an opportunity to be part of a vibrant office environment with a varied and exciting mix of amenities. -

101 DALSTON LANE a Boutique of Nine Newly Built Apartments HACKNEY, E8 101 DLSTN

101 DALSTON LANE A boutique of nine newly built apartments HACKNEY, E8 101 DLSTN 101 DLSTN is a boutique collection of just 9 newly built apartments, perfectly located within the heart of London’s trendy East End. The spaces have been designed to create a selection of well- appointed homes with high quality finishes and functional living in mind. Located on the corner of Cecilia Road & Dalston Lane the apartments are extremely well connected, allowing you to discover the best that East London has to offer. This purpose built development boasts a collection of 1, 2 and 3 bed apartments all benefitting from their own private outside space. Each apartment has been meticulously planned with no detail spared, benefitting from clean contemporary aesthetics in a handsome brick external. The development is perfectly located for a work/life balance with great transport links and an endless choice of fantastic restaurants, bars, shops and green spaces to visit on your weekends. Located just a short walk from Dalston Junction, Dalston Kingsland & Hackney Downs stations there are also fantastic bus and cycle routes to reach Shoreditch and further afield. The beautiful green spaces of London Fields and Hackney Downs are all within walking distance from the development as well as weekend attractions such as Broadway Market, Columbia Road Market and Victoria Park. • 10 year building warranty • 250 year leases • Registered with Help to Buy • Boutique development • Private outside space • Underfloor heating APARTMENT SPECIFICATIONS KITCHEN COMMON AREAS -

![Download/Chb/MESBD/MESBD.Zip [Last Accessed August 4, 2011]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8841/download-chb-mesbd-mesbd-zip-last-accessed-august-4-2011-608841.webp)

Download/Chb/MESBD/MESBD.Zip [Last Accessed August 4, 2011]

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 10 March 2015 Version of attached le: Accepted Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Kendall, E. and Montgomery, J. and Evans, J. and Stantis, C. and Mueller, V. (2013) 'Mobility, mortality, and the middle ages : identication of migrant individuals in a 14th century black death cemetery population.', American journal of physical anthropology., 150 (2). pp. 210-222. Further information on publisher's website: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.22194 Publisher's copyright statement: This is the accepted version of the following article: Kendall, E.J., Montgomery, J., Evans, J.A., Stantis, C. and Mueller, V. (2013), Mobility, mortality, and the middle ages: Identication of migrant individuals in a 14th century black death cemetery population. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 150 (2): 210-222, which has been published in nal form at http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.22194. This article may be used for non-commercial purposes in accordance With Wiley Terms and Conditions for self-archiving. Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. -

RDP SPEC GUIDE 09.Pdf

Flora London Marathon 2009 Pace Chart Mile Elite Wheel Wheel Elite 3:30 4:30 5:00 6:00 Women chair chair Men/ Pace Pace Pace Pace Spectator Men Women Mass Start 09:00 09:20 09:20 09:45 09:45 09:45 09:45 09:45 1 09:05 09:23 09:24 09:49 09:53 09:55 09:56 09:58 Guide 2 09:10 09:27 09:28 09:54 10:01 10:05 10:07 10:12 Flora London Marathon spectators are a crowd on the move! Most people like to try 3 09:15 09:31 09:32 09:59 10:09 10:15 10:19 10:26 and see runners at more than one location on the route and it’s great to soak up the 4 09:21 09:34 09:36 10:04 10:17 10:26 10:30 10:40 atmosphere, take in some of the landmarks, and perhaps pick up refreshments on 5 09:26 09:38 09:41 10:09 10:25 10:36 10:42 10:53 the way too. Here are some tips on getting around London to make your day safer 6 09:31 09:42 09:45 10:13 10:33 10:46 10:53 11:07 and more enjoyable. 7 09:36 09:45 09:49 10:18 10:41 10:57 11:05 11:21 8 09:42 09:49 09:53 10:23 10:49 11:07 11:16 11:35 here are hundreds of thousands of people lining On the opposite page is a specially formulated pace guide to 9 09:47 09:53 09:57 10:28 10:57 11:17 11:28 11:48 the route of the Flora London Marathon every year, help you follow the top flight action in the elite races. -

Children's Holiday Clubs & Sports Camps Tower Hamlets

Children's Holiday Clubs & Sports Camps Tower Hamlets Children's Easter, Summer, Christmas holiday camps and February, May, October half term clubs around Tower Hamlets, multi sport & activities, learning, workshops, courses, sports camps, water sports, parkour, kayaking, dance, art, IT, football, tennis, performing arts, swimming, sailing and many other options, also over half terms and school breaks for kids in Tower Hamlets, Whitechapel, Wapping, Millwall, Mile End, Stepney, Bethnal Green, Canary Wharf, Blackwall, Bow, Bromley-by-Bow, Cambridge Heath, Docklands, East Smithfield, Fish Island, Globe Town, Isle of Dogs, Cubitt Town, Leamouth, Limehouse, Old Ford, Poplar, Ratcliff, St George in the East, Shadwell, Spitalfields, Wapping areas. SEE Link for RESIDENTIAL camps, SUMMER Schools, Children's Activities ALSO VIRTUAL CAMPS & ACTIVITIES - https://www.020.co.uk/v/virtual-camps-and-activities/london.shtml The Strings ClubFeatured OPEN. Multi award-winning, Ofsted registered holiday camp at Halley House, E8 2DJ and Gainsborough Primary School E9 5ND - offering only the very best in childcare and music for children aged 4 - 11. Childcare vouchers accepted. Don't miss out! Nr Tower Hamlets E8 and E9 07931 037 186 Queen Mary University Students Union Sports holiday camps for 8 to 13 yo in Tower Hamlets offering the opportunity to participate in fun activities during the school holidays whilst learning new skills which include football, cricket, basketball, badminton, short tennis and more. Mile End Road Campus E1 4DH 020 7882 5765 Museum of London Docklands Museum of London Docklands' free virtual activities are wild & wonderful from the live stream family rave to reggae week, short talks, unguided secret tours, London audio walks, history & exhibition tours on YouTube channel & Facebook. -

Draft Future Shoreditch Area Action Plan

DRAFT FUTURE SHOREDITCH AREA ACTION PLAN black APRIL 2019 11 mm clearance all sides white 11 mm clearance all sides CMYK 11 mm clearance all sides CONTENTS PART A PART B 6 INTRODUCTION AND CONTEXT 32 THE AAP FRAMEWORK 7 Introduction 33 Vision statement 12 How to respond 34 Objectives 13 Structure of the AAP and how to use the document 36 Area Wide Policies 14 Planning policy context 37 Delivering Growth That Benefits All 19 Shoreditch today 41 Policy FS01 - Supporting New Jobs in Shoreditch 21 Key issues, opportunities and challenges 43 Policy FS02 - Achieving a Balanced Mix of Uses 25 Neighbourhoods 45 Tackling Affordability in Shoreditch 49 Policy FS03 - Providing Affordable Places of Work 51 Policy FS04 - Delivering New Genuinely Affordable Homes 54 Supporting a vibrant, diverse and accessible day, evening and night-time economy 57 Policy FS05 - Supporting Arts, Culture, Entertainment and Retail 59 Policy FS06 - Local Shops 61 High Quality Places and Buildings 63 Policy FS07 - Delivering High Quality Design 65 Policy FS08 - Managing Building Heights 67 Promoting More Sustainable and Improved Public Realm 69 Policy FS09 - Delivering High Quality Public Realm PART C PART D 76 SHAPING LOCAL NEIGHBOURHOODS 148 DELIVERY AND IMPLEMENTATION 79 Neighbourhood 01: The Edge of the City 149 Implementation of Policy 80 Policy N01 - The Edge of the City Neighbourhood 149 Implementation Plan 82 Neighbourhood 02: Central Shoreditch 150 Table 3. Implementation Plan - Public Realm Projects 84 Policy N02 - The Central Shoreditch Neighbourhood 153 Appendix