Psychiatric Complications of Erimin Abuse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Benzodiazepines

Benzodiazepines Using benzodiazepines in Children and Adolescents Overview Benzodiazepines are group of medications used to treat several different conditions. Some examples of these medications include: lorazepam (Ativan®); clonazepam (Rivotril®); alprazolam (Xanax®) and oxazepam (Serax®). Other benzodiazepine medications are available, but are less commonly used in children and adolescents. What are benzodiazepines used for? Benzodiazepines may be used for the following conditions: • anxiety disorders: generalized anxiety disorder; social anxiety disorder; post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD); panic attacks/disorder; excessive anxiety prior to surgery • sleep disorders: trouble sleeping (insomnia); waking up suddenly with great fear (night terrors); sleepwalking • seizure disorders (epilepsy) • alcohol withdrawal • treatment of periods of extreme slowing or excessive purposeless motor activity (catatonia) Your doctor may be using this medication for another reason. If you are unclear why this medication is being prescribed, please ask your doctor. How do benzodiazepines work? Benzodiazepines works by affecting the activity of the brain chemical (neurotransmitter) called GABA. By enhancing the action of GABA, benzodiazepines have a calming effect on parts of the brain that are too excitable. This in turn helps to manage anxiety, insomnia, and seizure disorders. How well do benzodiazepines work in children and adolescents? When used to treat anxiety disorders, benzodiazepines decrease symptoms such as nervousness, fear, and excessive worrying. Benzodiazepines may also help with the physical symptoms of anxiety, including fast or strong heart beat, trouble breathing, dizziness, shakiness, sweating, and restlessness. Typically, benzodiazepines are prescribed to manage anxiety symptoms that are uncomfortable, frightening or interfere with daily activities for a short period of time before conventional anti-anxiety treatments like cognitive-behavioural therapy or anti-anxiety takes effect. -

Benzodiazepine Group ELISA Kit

Benzodiazepine Group ELISA Kit Benzodiazepine Background Since their introduction in the 1960s, benzodiazepines have been widely prescribed for the treatment of anxiety, insomnia, muscle spasms, alcohol withdrawal, and seizure-prevention as they are depressants of the central nervous system. Despite the fact that they are highly effective for their intended use, benzodiazepines are prescribed with caution as they can be highly addictive. In fact, researchers at NIDA (National Institute on Drug Abuse) have shown that addiction for benzodiazepines is similar to that of opioids, cannabinoids, and GHB. Common street names of benzodiazepines include “Benzos” and “Downers”. The five most encountered benzodiazepines on the illicit market are alprazolam (Xanax), lorazepam (Ativan), clonazepam (Klonopin), diazepam (Valium), and temazepam (Restori). The method of abuse is typically oral or snorted in crushed form. The DEA notes a particularly high rate of abuse among heroin and cocaine abusers. Designer benzodiazepines are currently offered in online shops selling “research chemicals”, providing drug abusers an alternative to prescription-only benzodiazepines. Data defining pharmacokinetic parameters, drug metabolisms, and detectability in biological fluids is limited. This lack of information presents a challenge to forensic laboratories. Changes in national narcotics laws in many countries led to the control of (phenazepam and etizolam), which were marketed by pharmaceutical companies in some countries. With the control of phenazepam and etizolam, clandestine laboratories have begun researching and manufacturing alternative benzodiazepines as legal substitutes. Delorazepam, diclazepam, pyrazolam, and flubromazepam have emerged as compounds in this class of drugs. References Drug Enforcement Administration, Office of Diversion Control. “Benzodiazepines.” http://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/drugs_concern/benzo_1. -

Execution by . . . Heroin?: Why States Should Challenge the FDA's Ban

N2_BERGS_UPDATED (DO NOT DELETE) 1/15/2017 9:55 AM Execution by . Heroin?: Why States Should Challenge the FDA’s Ban on the Importation of Sodium Thiopental Matthew C. Bergs* ABSTRACT: This Note traces the history of the lethal injection drug shortage and its impact on how states carry out the death penalty. Though this topic has received much attention in recent years, relatively little attention has been paid to the D.C. Circuit’s decision in Cook v. FDA, which exacerbated the shortage. In Cook, the D.C. Circuit enjoined the FDA from exercising its enforcement discretion to allow the importation of sodium thiopental, the primary anesthetic used by states in lethal injection executions. This decision is significant because it effectively required the FDA to ban the importation of sodium thiopental, forcing states to find other ways to carry out executions. Many states have turned to new drugs and manufacturers, while others have returned to past methods of execution. However, states’ use of alternative drugs and manufacturers has had disastrous consequences, and the return to old methods of execution constitutes an unacceptable regression towards inhumane and barbaric punishment. Thus, this Note argues that states should make every effort to obtain sodium thiopental. Potential avenues to obtain the drug include adhering to the FDA’s regulations or litigating against the FDA’s regulations. Renewed access to sodium thiopental will resolve many of the problems plaguing the administration of lethal injection. I. INTRODUCTION & BACKGROUND .................................................. 762 A. HISTORY OF LETHAL INJECTION AS A METHOD OF EXECUTION ... 763 B. DEVELOPMENT OF THE LETHAL INJECTION DRUG SHORTAGE .... -

Calculating Equivalent Doses of Oral Benzodiazepines

Calculating equivalent doses of oral benzodiazepines Background Benzodiazepines are the most commonly used anxiolytics and hypnotics (1). There are major differences in potency between different benzodiazepines and this difference in potency is important when switching from one benzodiazepine to another (2). Benzodiazepines also differ markedly in the speed in which they are metabolised and eliminated. With repeated daily dosing accumulation occurs and high concentrations can build up in the body (mainly in fatty tissues) (2). The degree of sedation that they induce also varies, making it difficult to determine exact equivalents (3). Answer Advice on benzodiazepine conversion NB: Before using Table 1, read the notes below and the Limitations statement at the end of this document. Switching benzodiazepines may be advantageous for a variety of reasons, e.g. to a drug with a different half-life pre-discontinuation (4) or in the event of non-availability of a specific benzodiazepine. With relatively short-acting benzodiazepines such as alprazolam and lorazepam, it is not possible to achieve a smooth decline in blood and tissue concentrations during benzodiazepine withdrawal. These drugs are eliminated fairly rapidly with the result that concentrations fluctuate with peaks and troughs between each dose. It is necessary to take the tablets several times a day and many people experience a "mini-withdrawal", sometimes a craving, between each dose. For people withdrawing from these potent, short-acting drugs it has been advised that they switch to an equivalent dose of a benzodiazepine with a long half life such as diazepam (5). Diazepam is available as 2mg tablets which can be halved to give 1mg doses. -

IV Induction Agents

Intravenous drugs used for the induction of anaesthesia Dr Tom Lupton, Specialist Registrar in Anaesthesia Dr Oliver Pratt, Consultant Anaesthetist Salford Royal Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Salford, UK Key questions This tutorial reviews the basic pharmacology of common intravenous (IV) anaesthetic drugs. By the end of the tutorial, you should be able to decide on the most appropriate drug to use in the situations below and for what reason: 1. A patient with intestinal obstruction requires an emergency laparotomy. 2. A patient with a history of throat cancer, showing marked stridor and signs of respiratory distress, requires a tracheostomy. 3. A patient requiring a burn dressing change. 4. A patient with a history of heart failure requires a general anaesthetic. 5. A dehydrated hypovolaemic patient requires an emergency general anaesthetic. 6. A patient with porphyria comes for an inguinal hernia repair and is requesting a general anaesthetic. 7. A patient requires sedation on the intensive care unit. 8. Anaesthesia in the prehospital environment. What are IV induction drugs? These are drugs that, when given intravenously in an appropriate dose, cause a rapid loss of consciousness. This is often described as occurring within “one arm-brain circulation time” that is simply the time taken for the drug to travel from the site of injection (usually the arm) to the brain, where they have their effect. They are used: • To induce anaesthesia prior to other drugs being given to maintain anaesthesia. • As the sole drug for short procedures. • To maintain anaesthesia for longer procedures by intravenous infusion. • To provide sedation. The concept of intravenous anaesthesia was born in 1932, when Wesse and Schrapff published their report into the use of hexobarbitone, the first rapidly acting intravenous drug. -

Pharmacological Treatments Protocols of Alcohol and Drugs Abuse

Pharmacological Treatments Protocols of Alcohol and Drugs Abuse 1 Purpose of the protocols: Use and abuse of drugs and alcohol is becoming common and can have serious and harmful consequences on individuals, families, and society. Care with a tailored treatment program and follow-up options can be crucial to success. Treatment should include both medical and mental health services as needed in managing withdrawal symptoms, prevent relapse, and treat co- occurring conditions. Follow-up care may include community- or family-based recovery support systems. These protocols have been developed to guide medical practitioners and nurses in the use of the most effective available treatments of alcohol and drug abuse in the in-patient and out- patient settings and serve as a framework for clinical decisions and supporting best practices. Targeted end users: • Psychiatry and Addiction Medicine Consultants, Specialists and Residents • Nurses • Psychiatry clinical pharmacists • Pharmacists 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Chapter (1) Alcohol 4 3.1 Introduction 4 3.2 Intoxication 4 3.3 Withdrawal 7 2. Chapter (2) Benzodiazepines 21 2.1 Introduction 21 2.2 Intoxication 21 2.3 Withdrawal 22 3. Chapter (3) Opioids 27 3.1 Introduction 27 3.2 Intoxication 28 3.3 Withdrawal 29 4. Chapter (4) Psychostimulants 38 2.1 Introduction 38 2.2 Intoxication 39 2.3 Withdrawal 40 5. Chapter (5) Cannabis 41 3.1 Introduction 41 3.2 Intoxication 41 3.3 Withdrawal 43 6. References 46 3 CHAPTER 1 ALCOHOL INTRODUCTION Alcohol is a Central Nervous System (CNS) depressant. Its’ psychoactive properties contribute to changes in mood, cognition and behavior. -

Benzodiazepines

Benzodiazepines CRIT program May 2011 Alex Walley, MD, MSc Assistant Professor of Medicine Boston University School of Medicine Medical Director, Opioid Treatment Program Boston Public Health Commission Medical Director, Overdose Prevention Pilot Program Massachusetts Department of Public Health CRIT 2011 Learning objectives At the end of this session, you should: 1. Understand why people use benzodiazepines 2. Know the characteristics of benzodiazepine intoxication and withdrawal syndromes 3. Understand the consequences of these drugs 4. Know the current options for treatment of benzodiazepine dependence CRIT 2011 Roadmap 1. Case and controversies 2. History and Epidemiology 3. Benzo effects 4. Treatment CRIT 2011 Case • 29 yo man presents for follow-up at methadone clinic after inpatient admission for femur fracture from falling onto subway track from platform. • Treated with clonazepam since age 16 for panic disorder. Takes 6mg in divided doses daily. Missed his afternoon dose, the day of the accident • Started using heroin at age 23 • On methadone maintenance for 1 year, doing well, about to get his first take home CRIT 2011 Thoughts • Did BZDs cause his fall? – or did not taking BZDs cause his fall? • Is he addicted to benzos? • Should he come off of BZDs? How? • If not, how do we keep him safe? • Should he get take homes? • Did teenage BZD treatment cause his heroin addiction? CRIT 2011 History and Epidemiology CRIT 2011 History • First discovered in 1954 by a Austrian scientist, Leo Sternbach Æ Librium • 1963 Æ Valium • Used for -

Midazolam Injection, USP

Midazolam Injection, USP Rx only PHARMACY BULK PACKAGE – NOT FOR DIRECT INFUSION WARNING ADULTS AND PEDIATRICS: Intravenous midazolam has been associated with respiratory depression and respiratory arrest, especially when used for sedation in noncritical care settings. In some cases, where this was not recognized promptly and treated effectively, death or hypoxic encephalopathy has resulted. Intravenous midazolam should be used only in hospital or ambulatory care settings, including physicians’ and dental offices, that provide for continuous monitoring of respiratory and cardiac function, i.e., pulse oximetry. Immediate availability of resuscitative drugs and age- and size-appropriate equipment for bag/valve/mask ventilation and intubation, and personnel trained in their use and skilled in airway management should be assured (see WARNINGS). For deeply sedated pediatric patients, a dedicated individual, other than the practitioner performing the procedure, should monitor the patient throughout the procedures. The initial intravenous dose for sedation in adult patients may be as little as 1 mg, but should not exceed 2.5 mg in a normal healthy adult. Lower doses are necessary for older (over 60 years) or debilitated patients and in patients receiving concomitant narcotics or other central nervous system (CNS) depressants. The initial dose and all subsequent doses should always be titrated slowly; administer over at least 2 minutes and 1 allow an additional 2 or more minutes to fully evaluate the sedative effect. The dilution of the 5 mg/mL formulation is recommended to facilitate slower injection. Doses of sedative medications in pediatric patients must be calculated on a mg/kg basis, and initial doses and all subsequent doses should always be titrated slowly. -

Benzodiazepines

Benzodiazepines CRIT program May 2010 Alex Walley, MD, MSc Assistant Professor of Medicine Boston University School of Medicine Medical Director, Opioid Treatment Program Boston Public Health Commission Medical Director, Overdose Prevention Pilot Program Massachusetts Department of Public Health CRIT 2010 Learning objectives At the end of this session, you should: 1. Understand why people use benzodiazepines 2. Know the characteristics of benzodiazepine intoxication and withdrawal syndromes 3. Understand the consequences of these drugs 4. Know the current options for treatment of benzodiazepine dependence CRIT 2010 Roadmap 1. Case and controversies 2. History and Epidemiology 3. Benzo effects 4. Treatment CRIT 2010 Case • 29 yo man presents for follow-up at methadone clinic after inpatient admission for femur fracture from falling onto subway track from platform. • Treated with clonazepam since age 16 for panic disorder. Takes 6mg in divided doses daily. Missed his afternoon dose, the day of the accident • Started using heroin at age 23 • On methadone maintenance for 1 year, doing well, about to get his first take home CRIT 2010 Thoughts • Did BZDs cause his fall? – or did not taking BZDs cause his fall? • Should he get take homes? • Is it possible for him to come off of BZDs? How? • Did teenage BZD treatment cause his heroin addiction? CRIT 2010 History and Epidemiology CRIT 2010 History • First discovered in 1954 by a Austrian scientist, Leo Sternbach Æ Librium • 1963 Æ Valium • Used for anxiety, seizures, withdrawal, insomnia, drug- -

Valerian SUSAN HADLEY, M.D., Middlesex Hospital, Middletown, Connecticut JUDITH J

COMPLEMENTARY AND ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE Valerian SUSAN HADLEY, M.D., Middlesex Hospital, Middletown, Connecticut JUDITH J. PETRY, M.D., Vermont Healing Tools Project, Brattleboro, Vermont Valerian is a traditional herbal sleep remedy that has been studied with a variety of methodologic designs using multiple dosages and preparations. Research has focused on subjective evaluations of sleep patterns, particularly sleep latency, and study populations have primarily consisted of self-described poor sleepers. Valerian improves subjective experiences of sleep when taken nightly over one- to two-week periods, and it appears to be a safe sedative/hypnotic choice in patients with mild to moderate insomnia. The evi- dence for single-dose effect is contradictory. Valerian is also used in patients with mild anxiety, but the data supporting this indication are limited. Although the adverse effect profile and tolerability of this herb are excellent, long-term safety studies are lacking. (Am Fam Physician 2003;67:1755-8. Copyright©2003 American Academy of Family Physicians) he root of valerian, a perennial triates, valeric acid) and interaction with neu- herb native to North America, rotransmitters such as GABA (valeric acid and Asia, and Europe, is used most unknown fractions).2,3 commonly for its sedative and hypnotic properties in patients Uses and Efficacy Twith insomnia, and less commonly as an SEDATIVE/HYPNOTIC anxiolytic. Multiple preparations are available, Several clinical studies have shown that and the herb is commonly combined with valerian is effective in the treatment of insom- other herbal medications. This review nia, most often by reducing sleep latency. A addresses only studies that used valerian root double-blind, placebo-controlled trial4 com- as an isolated herb. -

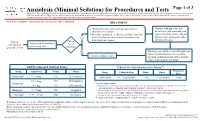

Anxiolysis (Minimal Sedation) for Procedures and Tests

Anxiolysis (Minimal Sedation) for Procedures and Tests Page 1 of 3 Disclaimer: This algorithm has been developed for MD Anderson using a multidisciplinary approach considering circumstances particular to MD Anderson’s specific patient population, services and structure, and clinical information. This is not intended to replace the independent medical or professional judgment of physicians or other health care providers in the context of individual clinical circumstances to determine a patient's care. This algorithm should not be used to treat pregnant women. Note: Refer to UTMDACC Institutional Policy #CLN0502 for complete information. TREATMENT ● Document mental status and vital signs prior to Continue with procedure and administering sedation document mental status and vital ● Determine appropriate medication and dose based on signs after administering sedation onset of action (see chart below) of anxiolytic for and prior to beginning procedure Yes 1 desired patient response and post-procedure Patient Patient Assess need for anxiolysis scheduled for needs prior to procedure procedure or test anxiolysis? No Discharge patient when clinically stable and follow institutional processes regarding Continue with procedure discharge instructions and criteria for both inpatient and outpatient settings 2,3 Adult Recommended Anxiolysis Dosing Pediatric Recommended Anxiolysis Dosing3,5,6 Maximum Drug Adult Dose Route Onset Drug Pediatric Dose Route Onset Dose 4 Midazolam 5 – 10 mg PO 10-30 minutes Midazolam 0.5 – 1 mg/kg/dose PO 10-20 minutes 5 mg 0.5 – 2 mg PO 30-60 minutes Lorazepam 5 Pediatric considerations: 1 – 4 mg IM 20-30 minutes ● Consider lower dosing strategies for patients with cardiac or respiratory compromise, and those who received concomitant opiates, benzodiazepines or similar synergistic sedative medications. -

CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDE LINES for MANAGEMENT of BARBITURATES and BENZODIAZEPINE DEPENDENCE Dr

CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDE LINES FOR MANAGEMENT OF BARBITURATES AND BENZODIAZEPINE DEPENDENCE Dr. Shiv Gautam1, Dr. Sanjaya Jain2, Dr. Lalit Batra3, Dr. Preeti Lodha4 INTRODUCTION : Over the time (Benzodiazepines introduced in 1960) it was recognised that Benzodiazepines could produce severe physiological dependence (American psychiatric Association task force on Benzodiazepines dependence 1990) and could be a drug of abuse. Nonetheless, their medical utility in treatment of disabling anxiety, episodic sleep disturbances and seizure has made them indispensable to medical practice. The sedative-hypnotics include a chemically diverse group of medications include prescribing sleeping medications, and most medications used for treatment of anxiety and insomnia. 1. Pharmacologically alcohol is appropriately included among sedative hypnotics however it is generally considered separately as it is in DSM- IV- TR (American Psychiatric Association - 2000). 2. Although Buspirone is marketed for the treatment of anxiety its pharmacological profile is sufficiently different that it is not included among sedative- hypnotics. 3. Antidepressants may also have anti-anxiety properties and their sedative properties are often of clinical utility in sleep induction. They too are usually excluded form sedative- hypnotics classification. Benzodiazepines abuse and dependence Benzodiazepines are not common primary drugs of abuse; most people do not find the effects of Benzodiazepines reinforcing or pleasurable (Chutuape and de wit 1994; de wit et al 1984) sedative- hypnotics' abusers prefer pentobarbital to diazepam, even at high doses (Griffiths et al 1980). Benzodiazepines are commonly misused and abused among patients receiving methadone maintenance (Barnas et al 1992; Iguchietal 1993). 1-Sr. Professor, 2-Assoclate Professor, 3-Asstt. Professor, 4-Resident Doctor Psychiatric Centre, SMS Medical College, Jaipur (66) Table 1: Medications usually included In the category of Sedative hypnotics Dose equal to 30 mg.