CONTRACTOR INDUCTION HANDBOOK Minimum Health & Safety Standard for Contractors VERSION: 2015 – 02

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Permits-To-Work in the Process Industries

SYMPOSIUM SERIES NO. 151 # 2006 IChemE PERMITS-TO-WORK IN THE PROCESS INDUSTRIES John Gould Environmental Resources Management, Suite 8.01, 8 Exchange Quay, Manchester M5 3EJ; [email protected] The paper presents the collective results from a number of Safety Management System audits. The audit protocol is based on the Health and Safety Executive pub- lication ‘Successful health and safety management’ and takes into account formal (written) and informal procedures as well as their implementation. Focused on permit-to-work systems, these have shown a number of common failings. The most common failure in implementing a permit-to-work system is the issue of too many permits. However, the audit protocol considers the whole risk control system. The failure to ‘close’ the management loop with an effective regular review process is the largest obstacle to an effective permit system. INTRODUCTION ‘Permits save lives – give them proper attention’. This is a startling statement made by the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) in its free leaflet IND(G) 98 (Rev 3) PTW systems. The leaflet goes on to state that two thirds of all accidents in the chemical industry are main- tenance related, with the permit-to-work (PTW) failures being the largest single cause. Given these facts, it comes as no surprise that PTW systems are a key part in the provision of a safe working environment. Over the past four years Environmental Resources Management (ERM) has been auditing PTW systems as part of its key risk control systems audits. Numerous systems have been evaluated from a wide rage of industries, covering personal care products man- ufacturing to refinery operations. -

Generic Procedures for Assessment and Response During a Radiological

IAEA-TECDOC-1162 Generic procedures for assessment and response during a radiological emergency August 2000 The originating Section of this publication in the IAEA was: Radiation Safety Section International Atomic Energy Agency Wagramer Strasse 5 P.O. Box 100 A-1400 Vienna, Austria Emended version, March 2013. Details of revisions are available at: www.pub.iaea/books/ GENERIC PROCEDURES FOR ASSESSMENT AND RESPONSE DURING A RADIOLOGICAL EMERGENCY IAEA, VIENNA, 2000 IAEA-TECDOC-1162 ISSN 1011–4289 © IAEA, 2000 Printed by the IAEA in Austria August 2000 FOREWORD One of the most important aspects of managing a radiological emergency is the ability to promptly and adequately determine and take actions to protect members of the public and emergency workers. Radiological accident assessment must take account of all critical information available at any time and must be an iterative and dynamic process aimed at reviewing the response as more detailed and complete information becomes available. This manual provides the tools, generic procedures and data needed for an initial response to a non-reactor radiological accident. This manual is one out of a set of IAEA publications on emergency preparedness and response, including Method for the Development of Emergency Response Preparedness for Nuclear or Radiological Accidents (IAEA-TECDOC-953), Generic Assessment Procedures for Determining Protective Actions During a Reactor Accident (IAEA-TECDOC-955) and Intervention Criteria in a Nuclear or Radiation Emergency (Safety Series No. 109). The procedures and data in this publication have been prepared with due attention to accuracy. However, as part of the ongoing revision process, they are undergoing detailed quality assurance checks; comments are welcomed, and following a period of time that will have allowed for a more extensive review, the IAEA will revise the publication as part of the process of continuous improvement. -

Cricothyrotomy

NURSING Cricothyrotomy: Assisting with PRACTICE & SKILL What is Cricothyrotomy? › Cricothyrotomy (CcT; also called thyrocricotomy, inferior laryngotomy, and emergency airway puncture) is an emergency surgical procedure that is performed to secure a patient’s airway when other methods (e.g., nasotracheal or orotracheal intubation) have failed or are contraindicated. Typically, CcT is performed only when intubation, delivery of oxygen, and use of ventilation are not possible • What: CcT is a type of tracheotomy procedure used in emergency situations (e.g., when a patient is unable to breathe through the nose or mouth). The two basic types of CcT are needle CcT (nCcT) and surgical CcT (sCcT). Both types of CcTs result in low patient morbidity when performed by a trained clinician. Compared with the sCcT method, the nCcT method requires less time to set up and is associated with less bleeding and airway trauma • How: Ideally, a CcT is performed within 30 seconds to 2 minutes by making an incision or puncture through the skin and the cricothyroid membrane (i.e., the thin part of the larynx [commonly called the voice box])that is between the cricoid cartilage and the thyroid cartilage) into the trachea –An nCcT is a temporary emergency procedure that involves the use of a catheter-over-needle technique to create a small opening. Because it involves a relatively small opening, it is not suitable for use in extended ventilation and should be followed by the performance of a surgical tracheotomy when the patient is stabilized. nCcT is the only type of CcT that is recommended for children who are under 10 years of age - A formal tracheotomy is a more complex procedure in which a surgical incision is made in the lower part of the neck, through the thyroid gland, and into the trachea. -

Mediating Role of Psychosocial Hazard: an Integrated Modelling Approach

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Impact of Safety Culture on Safety Performance; Mediating Role of Psychosocial Hazard: An Integrated Modelling Approach Gehad Mohammed Ahmed Naji 1,*, Ahmad Shahrul Nizam Isha 1, Mysara Eissa Mohyaldinn 2, Stavroula Leka 3 , Muhammad Shoaib Saleem 1, Syed Mohamed Nasir Bin Syed Abd Rahman 4 and Mohammed Alzoraiki 5 1 Department of Management & Humanities, Universiti Teknologi PETRONAS, Seri Iskandar 32610, Perak, Malaysia; [email protected] (A.S.N.I.); [email protected] (M.S.S.) 2 Department of Petroleum Engineering, Universiti Teknologi PETRONAS, Seri Iskandar 32610, Perak, Malaysia; [email protected] 3 Cork University Business School, University College Cork, T12 K8AF Cork, Ireland; [email protected] 4 Petronas Group Technology Solutions, Bandar Baru Bangi 43000, Selangor, Malaysia; [email protected] 5 Department of Technology Management and Business, Universiti Tun Hussein Onn Malaysia, Parit Raja 86400, Johor, Malaysia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: We conceptualize that safety culture (SC) has a positive impact on employee’s safety performance by reducing their psychosocial hazards. A higher level of safety culture environment reduces psychosocial hazards by improving employee’s performance toward safety concerns. The Citation: Naji, G.M.A.; Isha, A.S.N.; purpose of this study was to evaluate how psychosocial hazard mediates the relationship between Mohyaldinn, M.E.; Leka, S.; Saleem, safety culture and safety performance. Data were collected from 380 production employees in M.S.; Rahman, S.M.N.B.S.A.; three states of Malaysia from the upstream oil and gas sector. -

Lockout Tagout at a Glance

4/9/2015 Lockout/Tagout Beyond the Products: A Roadmap to a Sustainable Lockout Program Edwin Ojeda Lockout Tagout at a Glance Lockout • Physically ensuring a machine is inoperable while repairs or adjustments are made with the use of a padlock and a suitable device. Tagout • Clearly communicating to workers that the equipment is being serviced with labels and tags when lockout is not a viable option. When it comes to your lockout program, your employees are the priority. They face equipment challenges everyday on the shop floor and deserve protection they can trust. The Intent Behind Lockout Tagout – Protecting Employees OSHA’s intent was to protect: • General industry workers performing servicing and/or maintenance on machines or equipment and who are exposed to the unexpected energization, startup or release of hazardous energy. OSHA 29CFR1910.147 1 4/9/2015 Regulatory Basics – U.S. OSHA 29CFR OSHA 29CFR ANSI 1910.147 1910.333 Z244.1-2003 Control of Hazardous LOTO & Alternative Electrical Safety Energy Methods It’s Not Just the United States Canada • CSA Z460:2013 • Control of Hazardous Energy Europe • 2006/42/EC – Machine Directive • 2009/104/EC – Work Directive International • IEC 60204 – Safety of Machinery (Electrical) • ISO 14118 – Prevention of Unexpected Start-Up The Key to Sustainability Your Six Steps to LOTO Compliance 2 4/9/2015 Six Steps in Creating a Sustainable Solutions STEP 1 STEP 2 STEP 3 Develop and Create and post Identify and mark document your written, equipment- all energy control energy control specific lockout -

Safety at Work Permit-To-Work Systems… Electronic Or Paper?

Safety at Work Permit-to-work systems… electronic or paper? First of all let’s be clear about what we mean by an electronic permit-to-work system. There is widespread misunderstanding and confusion about this term. Some folk understand this to mean that it simply refers to the use of a computer as a means of generating and printing a paper permit, rather than having to rely on doing this work entirely by hand, in effect, merely an “electronic form” of a paper permit. Whereas, in reality, an electronic permit to work system, like aSap’s PCMS (www.safetyapplication.com) is something entirely more relevant to modern business needs. By harnessing the power and ease of use of modern technology and advanced application software development, aligned with best safety practice and risk assessment techniques, the advantages offered by this particular electronic permit-to-work system transcends the simple process of raising and issuing of permits. Just as importantly, it provides the necessary interface and means of access to a whole spectrum of safety-related management information, as well as providing the impetus and behaviour to underpin an effective and efficient safety culture and operational regime. A far cry, indeed, from the obviously inherent limitations of a paper-based system. “An electronic permit to So why change from a paper based system? A sentiment often work system, like aSap’s expressed runs along the lines of: “We’ve managed with our PCMS, is something entirely paper-based system for years, why should we change?” or, “If more relevant to modern it’s not broken, why fix it?” These are perfectly reasonable business needs.” opinions if the business is small and relatively simple to run. -

Emergency Plan Checklist Center Name: License ID

Emergency Plan Checklist Center Name: License ID: Prepare written emergency procedures delineating the following: Location of the first aid kit and additional first aid supplies Name, address and telephone number of the physician retained by the center or of the health facility used in emergencies Procedure for obtaining emergency transportation Hospital and or clinic to which injured or ill children will be taken Phone numbers for police, fire, ambulance and Poison Control (National Poison Emergency Hotline at 800-222- 1222) Location of written authorization from parent(s) for emergency medical care for each child Diagram indicating how the center is to be evacuated in an emergency from each classroom and the outdoor play area Location of fire alarms and fire extinguishers Procedures for ensuring children’s safety and communicating with parents in the event of evacuation, lockdown, natural or civil disaster and other emergencies Plan for informing parents of their children’s whereabouts The local law enforcement agency or emergency management office that has been notified of the center’s identifying information as listed below: The center’s name and location The number and ages of children enrolled The number of staff The need for emergency transportation; the location to which children will be evacuated The plan for a lockdown The plan for reuniting children with their parents To Find Your County’s Office of Emergency Management Coordinators, Visit: http://ready.nj.gov/about-us/county-coordinators.shtml Other: Ensure emergency plan is posted for reference or is readily accessible in a designated location in the center Maintain 1 evacuation crib per 4 enrolled non-ambulatory infant/toddler children (if applicable) Staff have been trained in procedures for operating locking devices used for lockdown procedures (if applicable) Notes for Emergency Plan: OOL/10.28.2017 . -

CONFINED SPACE ENTRY PROGRAM Owner: Risk Management Document Number: EHS S-004 Revision No: 01 Date Last Revised: 08-2-2018

CONFINED SPACE ENTRY PROGRAM Owner: Risk Management Document number: EHS S-004 Revision No: 01 Date last revised: 08-2-2018 Contents 1.0 Applicability ......................................................................................................................................................2 2.0 Scope ...............................................................................................................................................................2 3.0 Definitions ........................................................................................................................................................2 4.0 Core Information and Requirements ...............................................................................................................4 5.0 Roles and Responsibilities ............................................................................................................................ 29 6.0 Goals, Objectives and Performance Measures ............................................................................................ 32 7.0 Training ......................................................................................................................................................... 33 8.0 Program Evaluation ...................................................................................................................................... 34 9.0 Resources .................................................................................................................................................... -

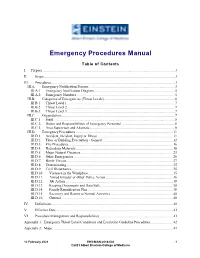

Emergency Procedures Manual

Emergency Procedures Manual Table of Contents I. Purpose ............................................................................................................................................ 3 II. Scope ........................................................................................................................................... 3 III. Procedures ................................................................................................................................... 3 III.A. Emergency Notification Process ........................................................................................... 3 III.A.1. Emergency Notification Diagram...................................................................................... 5 III.A.2. Emergency Numbers ........................................................................................................ 5 III.B. Categories of Emergencies (Threat Levels) ........................................................................... 6 III.B.1. Threat Level 1 .................................................................................................................. 7 III.B.2. Threat Level 2 .................................................................................................................. 7 III.B.3. Threat Level 3 .................................................................................................................. 7 III.C. Organization........................................................................................................................ -

Model SOP Standard Operating Procedure

Model SOP for Training Purposes Only Firetactics.com Model SOP Standard Operating Procedure Firetactics.com Paul Grimwood FIFireE ‐ SOP 1/Version 2/2009 1. TACTICAL DEPLOYMENT INTO FIRE INVOLVED STRUCTURES Sections 1. Purpose 1. Purpose The following bulletin serves as a training 2. Pre‐planning document that covers a range of critical 3. Information ‘in’ tasking issues associated with the safe 4. Risk Management and effective deployment of firefighters 5. Information ‘out’ into fire involved structures. It is not a 6. Situation Awareness complete SOP by any means but simply 7. Staffing stands to inform of a risk‐assessed 8. Water Supply process for compartment and structural 9. Primary Attack fire‐fighting. 10. Search & Rescue However, this document may serve as a 11. Securing Team Safety model upon which more detailed 12. Tactical Ventilation operational procedures may be 13. Primary (First Response) Command & Control developed. 14. Accountability 15. BA Emergency Procedure All students are strongly advised to follow 16. Communication their own departmental SOPs at all times. 17. Principal Officer (First Chief) Command & Control Any deviation from such procedure must 18. Large Volume Structures only be made with good reason and 19. High‐rise Buildings should be held accountable at a later stage. 20. The Most Common Reasons for Traumatic Fire‐fighter Life Losses 2. Pre‐planning It is essential that familiarization visits are made to all large volume structures, or those presenting excessive or unusual risks, so that plans may are organised and provided on‐site in special premises information boxes located at main entry points. Alternatively, these may be held on computer terminals and down loaded into a fire engine’s computer system as they arrive on‐scene. -

Safety Culture Maturity and Risk Management Maturity in Industrial Organizations

Safety Culture Maturity and Risk Management Maturity in Industrial Organizations Anastacio P. Goncalves*, Gabriel Kanegae*, Gustavo Leite* * Production Engineering, School of Engineering, Bahia Federal University Email: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract This article presents research about safety culture maturity and safety management maturity in three different types of organizations in Bahia, Brazil. The model and the questionnaire developed by Gonçalves Filho et al (2010) were used to identify both the maturity of safety culture and safety management maturity. The questionnaire was answered by 346 workers of 28 companies : 17 petrochemical, 5 footwear and 6 cable TV. The study also identified the safety management maturity, which revealed that higher levels of safety management maturity tended to display the features associated with higher levels of safety culture maturity. The results demonstrated that petrochemical companies are in a more advanced safety culture maturity stage than footwear industries as well as cable TV companies; the petrochemical ones are also more advanced relating risk management maturity than footwear and cable TV companies. These results indicate that safety culture can contribute for risk management to prosper. Keywords: safety culture; risk management; maturity. 1 Introduction Existing cultural issues in organizations can cause significant impediment or obstacles to the changes required for the implementation of a Risk management System (SMS). Therefore, it is essential to understand the maturity of the existing safety culture in a company in order to prepare the planning of changes, when necessary. An established safety culture is crucial for the development, success and good performance of the SMS (Choudhry et al., 2007; Ek et al., 2007; Hudson, 2003), because it is in a context where safety culture exists that attitudes and behavior of individuals in relation to safety are developed and persist (Mearns et al., 2003). -

Issue of Compliance with Use of Personal Protective Equipment Among Wastewater Workers Across the Southeast Region of the United States

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Issue of Compliance with Use of Personal Protective Equipment among Wastewater Workers across the Southeast Region of the United States Tamara Wright 1, Atin Adhikari 2,* , Jingjing Yin 2, Robert Vogel 2, Stacy Smallwood 1 and Gulzar Shah 1 1 Department of Health Policy and Community Health, Jiann-Ping Hsu College of Public Health, Georgia Southern University, Statesboro, GA 30460, USA; [email protected] (T.W.); [email protected] (S.S.); [email protected] (G.S.) 2 Department of Biostatistics, Epidemiology, and Environmental Health Sciences, Jiann-Ping Hsu College of Public Health, Georgia Southern University, Statesboro, GA 30460, USA; [email protected] (J.Y.); [email protected] (R.V.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 28 April 2019; Accepted: 3 June 2019; Published: 5 June 2019 Abstract: Wastewater workers are exposed to different occupational hazards such as chemicals, gases, viruses, and bacteria. Personal protective equipment (PPE) is a significant factor that can reduce or decrease the probability of an accident from hazardous exposures to chemicals and microbial contaminants. The purpose of this study was to examine wastewater worker’s beliefs and practices on wearing PPE through the integration of the Health Belief Model (HBM), identify the impact that management has on wastewater workers wearing PPE, and determine the predictors of PPE compliance among workers in the wastewater industry. Data was collected from 272 wastewater workers located at 33 wastewater facilities across the southeast region of the United States. Descriptive statistical analysis was conducted to present frequency distributions of participants’ knowledge and compliance with wearing PPE.