Hong Kong Youth Radicalization from the Perspective of Relative Deprivation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

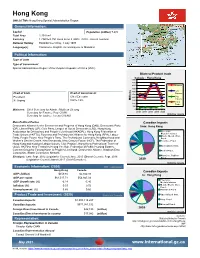

Hong Kong Official Title: Hong Kong Special Administration Region General Information

Hong Kong Official Title: Hong Kong Special Administration Region General Information: Capital Population (million) 7.474n/a Total Area 1,104 km² Currency 1 CAN$=5.791 Hong Kong $ (HKD) (2020 - Annual average) National Holiday Establishment Day, 1 July 1997 Language(s) Cantonese, English, increasing use of Mandarin Political Information: Type of State Type of Government Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Bilateral Product trade Canada - Hong Kong 5000 4500 4000 Balance 3500 3000 Can. Head of State Head of Government Exports 2500 President Chief Executive 2000 Can. Imports XI Jinping Carrie Lam Millions 1500 Total 1000 Trade 500 Ministers: Chief Secretary for Admin.: Matthew Cheung 0 Secretary for Finance: Paul CHAN 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 Statistics Canada Secretary for Justice: Teresa CHENG Main Political Parties Canadian Imports Democratic Alliance for the Betterment and Progress of Hong Kong (DAB), Democratic Party from: Hong Kong (DP), Liberal Party (LP), Civic Party, League of Social Democrats (LSD), Hong Kong Association for Democracy and People’s Livelihood (HKADPL), Hong Kong Federation of Precio us M etals/ stones Trade Unions (HKFTU), Business and Professionals Alliance for Hong Kong (BPA), Labour M ach. M ech. Elec. Party, People Power, New People’s Party, The Professional Commons, Neighbourhood and Prod. Worker’s Service Centre, Neo Democrats, New Century Forum (NCF), The Federation of Textiles Prod. Hong Kong and Kowloon Labour Unions, Civic Passion, Hong Kong Professional Teachers' Union, HK First, New Territories Heung Yee Kuk, Federation of Public Housing Estates, Specialized Inst. Concern Group for Tseung Kwan O People's Livelihood, Democratic Alliance, Kowloon East Food Prod. -

CHAPTER 3 Hong Kong Music Ecosphere

Abstract The people of Hong Kong experienced their deepest sense of insecurity and anxiety after the handover of sovereignty to Beijing. Time and again, the incapacity and lack of credibility of the SAR government has been manifested in various new policies or incidents. Hong Kong people’s anger and discontent with the government have reached to the peak. On July 1, 2003, the sixth anniversary of the hand-over of Hong Kong to China, 500,000 demonstrators poured through the streets of Hong Kong to voice their concerns over the proposed legislation of Article 23 and their dissatisfaction to the SAR government. And the studies of politics and social movement are still dominated by accounts of open confrontations in the form of large scale and organized rebellions and protests. If we shift our focus on the terrain of everyday life, we can find that the youth voice out their discontents by different ways, such as various kinds of media. This research aims to fill the gap and explore the relationship between popular culture and politics of the youth in Hong Kong after 1997 by using one of the local bands KingLyChee as a case study. Politically, it aims at discovering the hidden voices of the youth and argues that the youth are not seen as passive victims of structural factors such as education system, market and family. Rather they are active and strategic actors who are capable of negotiating with and responding to the social change of Hong Kong society via employing popular culture like music by which the youth obtain their pleasure of producing their own meanings of social experience and the pleasure of avoiding the social discipline of the power-bloc. -

Discourse, Social Scales, and Epiphenomenality of Language Policy: a Case Study of a Local, Hong Kong NGO

Discourse, Social Scales, and Epiphenomenality of Language Policy: A Case Study of a Local, Hong Kong NGO Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Tso, Elizabeth Ann Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 27/09/2021 12:25:43 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/623063 DISCOURSE, SOCIAL SCALES, AND EPIPHENOMENALITY OF LANGUAGE POLICY: A CASE STUDY OF A LOCAL, HONG KONG NGO by Elizabeth Ann Tso __________________________ Copyright © Elizabeth Ann Tso 2017 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the GRADUATE INTERDISCIPLINARY PROGRAM IN SECOND LANGUAGE ACQUISITION AND TEACHING In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2017 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Elizabeth Tso, titled Discourse, Social Scales, and Epiphenomenality of Language Policy: A Case Study of a Local, Hong Kong NGO, and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _______________________________________________ Date: (January 13, 2017) Perry Gilmore _______________________________________________ Date: (January 13, 2017) Wenhao Diao _______________________________________________ Date: (January 13, 2017) Sheilah Nicholas Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. -

Public Order Policing in Hong Kong the Mongkok Riot Kam C

PUBLIC ORDER POLICING IN HONG KONG THE MONGKOK RIOT KAM C. WONG Palgrave Advances in Criminology and Criminal Justice in Asia Palgrave Advances in Criminology and Criminal Justice in Asia Series Editors Bill Hebenton Criminology & Criminal Justice University of Manchester Manchester, UK Susyan Jou School of Criminology National Taipei University Taipei, Taiwan Lennon Y. C. Chang School of Social Sciences Monash University Melbourne, VIC, Australia This bold and innovative series provides a much needed intellectual space for global scholars to showcase criminological scholarship in and on Asia. Reflecting upon the broad variety of methodological traditions in Asia, the series aims to create a greater multi-directional, cross-national under- standing between Eastern and Western scholars and enhance the field of comparative criminology. The series welcomes contributions across all aspects of criminology and criminal justice as well as interdisciplinary studies in sociology, law, crime science and psychology, which cover the wider Asia region including China, Hong Kong, India, Japan, Korea, Macao, Malaysia, Pakistan, Singapore, Taiwan, Thailand and Vietnam. More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/14719 Kam C. Wong Public Order Policing in Hong Kong The Mongkok Riot Kam C. Wong Xavier University (Emeritus) Cincinnati, OH, USA Palgrave Advances in Criminology and Criminal Justice in Asia ISBN 978-3-319-98671-5 ISBN 978-3-319-98672-2 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-98672-2 Library of Congress Control -

Monthly Report HK

January 2011 in Hong Kong 31.1.2011 / No 85 A condensed press review prepared by the Consulate General of Switzerland in HK Economy + Finance HK still ranked world's freest economy: HK remains the world’s freest economy for the 17th straight year and ranked 1st out of 41 countries – according to a report released by the Heritage Foundation and the Wall Street Journal. The city’s score remains unchanged from last year at 89.7 out of 100 in the 2011 Index of Economic Freedom, with small declines in the score for government spending and labour freedom offsetting improvements in fiscal freedom, monetary freedom, and freedom from corruption. The report said HK is one of the world’s most competitive financial and business centres, demonstrating a high degree of resilience during the global financial crisis. City casts off shadow of global financial crisis: HK's economy is rebounding from the aftermath of the global financial crisis, with the public coffers enjoying the first eight-month surplus in three years. The latest announcement showed a far better financial picture than the government had forecast. In his budget speech in February, Financial Secretary John Tsang projected a net deficit of HK$25.2 billion for the current financial year. However, consensus estimates among most accounting firms now put the full financial year budget at a surplus of at least HK$60 billion. The reserves stood at HK$537 billion as of November 30, compared to HK$455.5 billion a year earlier. HK jobless rate falls to 4pc: HK's unemployment rate declined from 4.1 per cent in September to November last year to 4.0 per cent in October to December last year. -

World Bank Document

HNP DISCUSSION PAPER Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Economics of Tobacco Control Paper No. 21 Research on Tobacco in China: About this series... An annotated bibliography of research on tobacco This series is produced by the Health, Nutrition, and Population Family (HNP) of the World Bank’s Human Development Network. The papers in this series aim to provide a vehicle for use, health effects, policies, farming and industry publishing preliminary and unpolished results on HNP topics to encourage discussion and Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized debate. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper are entirely those of the author(s) and should not be attributed in any manner to the World Bank, to its affiliated organizations or to members of its Board of Executive Directors or the countries they represent. Citation and the use of material presented in this series should take into account this provisional character. For free copies of papers in this series please contact the individual authors whose name appears on the paper. Joy de Beyer, Nina Kollars, Nancy Edwards, and Harold Cheung Enquiries about the series and submissions should be made directly to the Managing Editor Joy de Beyer ([email protected]) or HNP Advisory Service ([email protected], tel 202 473-2256, fax 202 522-3234). For more information, see also www.worldbank.org/hnppublications. The Economics of Tobacco Control sub-series is produced jointly with the Tobacco Free Initiative of the World Health Organization. The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in this paper are entirely those of the authors and should not be attributed in any Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized manner to the World Health Organization or to the World Bank, their affiliated organizations or members of their Executive Boards or the countries they represent. -

Research Projects Research Outputs and Publications

Department of Anthropology RESEARCH PROJECTS Resettlement and Indigenous People: A Study of Long Geng Kenyah in Sarawak Natural Resources and Human Subsistence " TAN Chee Beng Strategies in South China Between 10000 and 10 July 2000 5000 Years Ago CUHK Special Grant for Conducting Research Abroad in Summer " LU Lie Dan z FU Xian Guo* 1 November 2000 This project is an up-dated study of the Kenyah CUHK Research Committee Funding (Direct people (an indigenous minority in Sarawak, Grants) Malaysia). Since my study in 1995, the people had been relocated to another site. The study investigates This project aims to investigate the environment, the initial effects of relocation on this people, and natural resources and human subsistence strategies sees how the people cope with their economic and during the period between 10,000 and 5,000 years social life in the relocated area. It contributes to the ago in South China, focusing in the Yong River study of indigenous people and development, and the valley in South Guangxi. This period was a crucial results are useful for comparison with the study of time in prehistory, particularly in East Asia, as indigenous people in China and elsewhere. agriculture occurred both in the Yangzi and the Theoretically the study contributes to the Yellow Valleys, with rice and millet being the major understanding of how disempowered people cultivars respectively. The emergence of agriculture articulate their local interests. was one of the greatest events in human history. It (SS00377) was based upon rice and millet cultivation that Chinese civilization was founded. Please refer to previous issues of this publication The progenitor of domesticated rice is the wild rice, a for more details of the following ongoing research grass still widely distributed in South China today. -

Volume 19 • Issue 21 • December 10, 2019

VOLUME 19 • ISSUE 21 • DECEMBER 10, 2019 IN THIS ISSUE: Beijing’s Reactions to November Developments Surrounding the Crisis in Hong Kong By Elizabeth Chen and John Dotson The CCP’s Renewed Focus on Ideological Indoctrination, Part 1: The 2019 Guidelines for “Patriotic Education” By John Dotson INSTC vs. BRI: The India-China Competition Over the Port of Chabahar and Infrastructure in Asia By Syed Fazl-e-Haider Facing Up to China’s Military Interests in the Arctic By Anne-Marie Brady Editor’s Note: This issue represents a slight departure from our standard format (usually consisting of an editor’s brief, and four contributors’ articles). Due to a number of significant developments related to Hong Kong that occurred during the month of November, we have presented in this issue a lengthy overview article that summarizes these developments, and discusses the reaction on the part of the Chinese central government. This issue also includes a featured in-depth article by Dr. Anne-Marie Brady about China’s military ambitions in the Arctic region. Because these articles are longer than our usual standards, this issue contains four pieces instead of the usual total of five. *** 1 ChinaBrief • Volume 19 • Issue 21 • December 10, 2019 Beijing’s Reactions to November Developments Surrounding the Crisis in Hong Kong By Elizabeth Chen and John Dotson Introduction The year 2019 has seen a gradually escalating crisis in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The territory has seen continuing unrest since mass protests first broke out in June, in response to a draft extradition law that would have allowed Hong Kong residents to be arrested and sent to mainland China for prosecution. -

Educational Provision for Ethnic Minority Students in Hong Kong: Meeting the Challenges of the Proposed Racial Discrimination Bill

Educational Provision for Ethnic Minority Students in Hong Kong: Meeting the Challenges of the Proposed Racial Discrimination Bill A Public Policy Research Project (HKIEd8001-PPR-2) First Interim Report Chief Investigator Professor Kerry J. Kennedy, Hong Kong Institute of Education Co-investigators Dr. JoAnn Phillion, Purdue University Dr. Ming Tak Hue, Hong Kong Institute of Education Submitted to Central Policy Unit, Hong Kong SAR Government The work described in this report was fully supported by a grant from the Central Policy Unit of the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region and the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China (Project No. HKIEd8001-PPR-2) Summary of Key Issues The following issues have been identified as necessary to ensure that the special needs of ethnic minority students are being met and therefore to forestall any potential action under the proposed Racial Discrimination Ordinance. 1. Teaching of Chinese as a second language is the single most important issue for ethnic minority students. EDB is making concerted efforts to prepare appropriate curriculum and the importance of this cannot be overestimated. The lack of Chinese language proficiency prevents ethnic minority students from progressing through the education system and is the most significant barrier to equity for these students. 2. In providing specific curriculum for teaching Chinese as a second language thought needs to be given to teacher education since first language and second language teaching require different skills and understandings. Second language curriculum is not just a modification of first language curriculum – it represents an entirely different context for teaching and learning. -

Hong Kong Official Title: Hong Kong Special Administration Region General Information

Hong Kong Official Title: Hong Kong Special Administration Region General Information: Capital Population (million) 7.n4/8a3 Total Area 1,104 km² Currency 1 CAN$=5.9657 Hong Kong $ (HKD) (2018 - Annual average) National Holiday Establishment Day, 1 July 1997 Language(s) Cantonese, English, increasing use of Mandarin Political Information: Type of State Type of Government Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Bilateral Product trade Canada - Hong Kong 5000 4500 4000 Balance 3500 s 3000 Can. Head of State Head of Government n Exports o 2500 i l l Can. President Chief Executive i 2000 Imports XI Jinping Carrie Lam M 1500 Total 1000 Trade 500 Ministers: Chief Secretary for Admin.: Matthew Cheung 0 Secretary for Finance: Paul CHAN 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 Statistics Canada Secretary for Justice: Teresa CHENG Main Political Parties Canadian Imports Democratic Alliance for the Betterment and Progress of Hong Kong (DAB), Democratic Party from: Hong Kong (DP), Liberal Party (LP), Civic Party, League of Social Democrats (LSD), Hong Kong Association for Democracy and People’s Livelihood (HKADPL), Hong Kong Federation of M ach. M ech. Elec. Prod . Trade Unions (HKFTU), Business and Professionals Alliance for Hong Kong (BPA), Labour Precious Party, People Power, New People’s Party, The Professional Commons, Neighbourhood and M et als/ st o nes Worker’s Service Centre, Neo Democrats, New Century Forum (NCF), The Federation of Hong B ase M et al Pro d . Kong and Kowloon Labour Unions, Civic Passion, Hong Kong Professional Teachers' Union, HK First, New Territories Heung Yee Kuk, Federation of Public Housing Estates, Concern Foo d Pro d . -

School Curriculum and Youth Political Participation in Hong Kong

Article YOUNG Conduit for Engagement? 26(2) 1–18 © 2017 SAGE Publications and School Curriculum and YOUNG Editorial Group SAGE Publications Youth Political Participation sagepub.in/home.nav DOI: 10.1177/1103308817711533 in Hong Kong http://you.sagepub.com Trevor Tsz-lok Lee1 Stephen Wing-kai Chiu2 Abstract Learning about political issues through the new core subject of Liberal Studies (LS) in senior secondary education in Hong Kong has become ‘socially problematic’ amid mounting concern of politicians and pundits who see a link between such learning and the recent waves of student protests. Using data from in-depth inter- views with senior secondary students in Hong Kong, we explore how politically dis- engaged and engaged youth experienced their LS learning and how they perceived and made sense of the relationship between LS learning and political participation or its absence. Our findings indicate that while there appear to be circumstances that give rise to diversified learning experiences, LS has little bearing on youth political participation or otherwise. Keywords Civic education, politicization, youth activism, liberal studies, Hong Kong Introduction There has been an underlying struggle in many Asian educational systems over attempts to depoliticize schools by designing civic education exclusively for incul- cating moral and cultural values (Lee, 2004; Murphy and Liu, 1998). Civic educa- tion in Hong Kong is no exception, but its peculiar historical and social contexts have shaped students’ conceptions of citizenship in distinctive ways (Kennedy et al., 2008; Tse, 2006). In the post-colonial era, Hong Kong’s education system has expe- rienced waves of significant reforms, including in the area of civic education, in order to meet emerging political and economic challenges at both the global and 1 Department of Sociology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong. -

In Hong Kong Qingxiang Feng1,*

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, Volume 496 Proceedings of the 2020 3rd International Conference on Humanities Education and Social Sciences (ICHESS 2020) Problems and Countermeasures in the Practice of "One Country, Two Systems" in Hong Kong Qingxiang Feng1,* 1Institute of Guangdong Hong Kong and Macao Development Studies, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, Guangdong510275, China * Corresponding author. Email:[email protected] ABSTRACT The practice of "One country, Two systems" in Hong Kong has made great achievements, but it also faces challenges in various fields. The prominent problems faced by "One country, Two systems" in the practice of Hong Kong at present include: the obstacles of Hong Kong's economic operation and the structural contradictions of Hong Kong society. In view of this, consciously defining Hong Kong's position in the country and actively integrating into the overall development strategy of the country is the key to solving the economic and social contradictions in Hong Kong. Key words: One country, Two systems, Hong Kong, Economy, Society, Countermeasures balance the tension between the market and the government? How to deal with the relationship between 1. INTRODUCTION efficiency and fairness? How to optimize the combination of economic internal factors and adapt to external We are in an era of problems. Problems are open, fearless, environment? Under "One country, Two systems", Hong and the voice of the times that influences all individuals [1]. Kong not only needs to face some universal economic Question consciousness haunts us like Kant's philosophy's development problems, but also needs to face new constant questioning of rationality.