BANGLADESH Executive Summary the Constitution and Other Laws And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sri Krishna Janmashtami

September 2008 Dedicated to His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, Founder-Acharya of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness Sri Krishna Janmashtami Srila Prabhupada: There are many devotees who are engaged in the propagation of Krishna consciousness, and they require help. So, even if one cannot directly practice the regulative principles of bhakti-yoga, he can try to help such work... Just as in business one requires a place to stay, some capital to use, some labor and some organization to expand, so Bhaktivedanta Manor's most Srila Prabhupada’. Inside a special the same is required in the service spectacular festival of the year took exhibition ship, constructed by the of Krishna. The only difference is place over the summer bank holiday resident monks, visitors appreciated that in materialism one works for weekend. 50,000 pilgrims attended the efforts of the glorious founder of sense gratification. The same work, on Sunday 24th August, observing ISKCON, Srila Prabhupada. however, can be performed for the the birth of Lord Krishna on Earth. Throughout the day kitchen staff satisfaction of Krishna, and that is Bank Holiday Monday attracted a worked solidly to prepare the 50,000 spiritual activity. further 30,000. plates of prasad (vegetarian food) BG: 12.10 purport Visitors walked through the partly- that were distributed freely to all the built New Gokul complex, making pilgrims. Spectacular Premiere their way to the colourful festival A dedicated children’s area featured Jayadeva das and the local 'Comm. site. The main marquee hosted a numerous activities including a unity' choir lit up the main stage varied stage programme ranging mini ‘main marquee’ where children with the premiere performance of from cultural dances to musical performed their carefully prepared devotional songs from Jayadev's extravaganzas. -

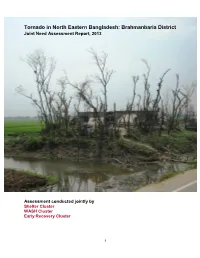

Brahmanbaria District Joint Need Assessment Report, 2013

Tornado in North Eastern Bangladesh: Brahmanbaria District Joint Need Assessment Report, 2013 Assessment conducted jointly by Shelter Cluster WASH Cluster Early Recovery Cluster 1 Table of Contents Executive Summary....................................................................................................... 6 Recommended Interventions......................................................................................... 8 Background.................................................................................................................... 10 Assessment Methodology.............................................................................................. 12 Key Findings.................................................................................................................. 14 Priorities identified by Upazila Officials.......................................................................... 18 Detailed Assessment Findings...................................................................................... 20 Shelter........................................................................................................................ 20 Water Sanitation & Hygiene....................................................................................... 20 Livelihoods.................................................................................................................. 21 Education.................................................................................................................... 24 -

Bangladesh Jobs Diagnostic.” World Bank, Washington, DC

JOBS SERIES Public Disclosure Authorized Issue No. 9 Public Disclosure Authorized DIAGNOSTIC BANGLADESH Public Disclosure Authorized Main Report Public Disclosure Authorized JOBS DIAGNOSTIC BANGLADESH Thomas Farole, Yoonyoung Cho, Laurent Bossavie, and Reyes Aterido Main Report © 2017 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank. 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA. Telephone: 202-473-1000; Internet: www.worldbank.org. Some rights reserved This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the govern- ments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Nothing herein shall constitute or be considered to be a limitation upon or waiver of the privileges and immunities of The World Bank, all of which are specifically reserved. Rights and Permissions This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo. Under the Creative Commons Attribution license, you are free to copy, distribute, transmit, and adapt this work, including for commercial purposes, under the following conditions: Attribution—Please cite the work as follows: Thomas Farole, Yoonyoung Cho, Laurent Bossavie, and Reyes Aterido. -

Bangladesh – Hindus – Awami League – Bengali Language

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: BGD30821 Country: Bangladesh Date: 8 November 2006 Keywords: Bangladesh – Hindus – Awami League – Bengali language This response was prepared by the Country Research Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Questions 1. Are Hindus a minority religion in Bangladesh? 2. How are religious minorities, notably Hindus, treated in Bangladesh? 3. Is the Awami League traditionally supported by the Hindus in Bangladesh? 4. Are Hindu supporters of the Awami League discriminated against and if so, by whom? 5. Are there parts of Bangladesh where Hindus enjoy more safety? 6. Is Bengali the language of Bangladeshis? RESPONSE 1. Are Hindus a minority religion in Bangladesh? Hindus constitute approximately 10 percent of the population in Bangladesh making them a religious minority. Sunni Muslims constitute around 88 percent of the population and Buddhists and Christians make up the remainder of the religious minorities. The Hindu minority in Bangladesh has progressively diminished since partition in 1947 from approximately 25 percent of the population to its current 10 percent (US Department of State 2006, International Religious Freedom Report for 2006 – Bangladesh, 15 September – Attachment 1). 2. How are religious minorities, notably Hindus, treated in Bangladesh? In general, minorities in Bangladesh have been consistently mistreated by the government and Islamist extremists. Specific discrimination against the Hindu minority intensified immediately following the 2001 national elections when the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) gained victory with its four-party coalition government, including two Islamic parties. -

ISKCON Pandava Sena

Bhaktivedanta Manor - your temple at your service Life, Service and Celebration Bhaktivedanta Manor functions 365 days a year. A dedicated team of devotees make it their mission to serve the at the Home of Lord Krishna entire community - through education, outreach, worship and support. • Catering is available for functions, parties and events. Egg-free vegetarian cakes, savouries and sweets can be ordered. Telephone Radharani’s Bakery: 01923 851009 • Radharani’s Shop sells devotional paraphernalia, books, CDs, DVDs, traditional clothing and paintings Visit on-site or order online from www.krishnashopping.com • Ceremonies, pujas and weddings can be conducted by Bhaktivedanta Manor’s trained priests Telephone 01923 851008 TAKE A COURSE Invest valuable time in the study of precious scripture: Bhagavad Gita, Srimad Bhagavatam, Sri Isopanisad & more Email: [email protected] JOIN A LOCAL GROUP Uncover your spiritual potential in the joyful company of like-minded families and individuals E-mail: [email protected] OFFER SOMETHING BACK Support the entire range of temple activities by becoming a Patron Contact Bhaktivedanta Manor Foundation - 01923 851008; email: [email protected] VOLUNTEER YOUR TIME Help is required in all areas imaginable: cooking, cleaning, teaching, office work, web design, media & technical, gardening, farming, garland making. Join a lively team and experience the unique service atmosphere at Bhaktivedanta Manor. E-mail: [email protected] • Contact us: [email protected] Helpful Websites Bhaktivedanta -

Bangladesh Is Located on a Geographic Location That Is Very

P1.86 A CLIMATOLOGICAL STUDY ON THE LANDFALLING TROPICAL CYCLONES OF BANGLADESH Tanveerul Islam and Richard E. Peterson* Wind Science and Engineering Research Center Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas 1. INTRODUCTION data and tracks for North Indian Ocean which includes of course the whole Bay of Bengal, the data is not easily Bangladesh lying between 20○34/ N and 26○38/ obtained. It is not clear whether Bangladesh N latitude, and with a 724 km long coast line is highly Meteorological Department has the records of land vulnerable to tropical cyclones and associated storm falling tropical cyclones in the Bangladesh coast, as surge. Bangladesh has experienced two of the most they did not respond to emails and no literature has deadly cyclones of the last century, one was in 1970 been found mentioning them as a source. So, the Joint and the other was some 20 years later in 1991. The Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) at Guam is the only former was the deadliest in the cyclone history with other source that keeps record for that area and gives it death count reached over 300,000. Bangladesh is the free of charge for the users. Using their data and some most densely populated country of the world with a from National Hurricane Center, Fleet Numerical density of 2,200 people per square mile, and most of the Meteorology and Oceanography Detachment (FNMOC) people are very poor. So, it is understandable that a prepared an online version software-Global Tropical large number of people inhabit the coastal areas and Cyclone Climatic Atlas (GTCCA Version 1.0), where all these people are always affected by windstorms and tropical cyclone data and tracks are listed for all the storm surge with lesser resilience due to poverty basins from as early as 1842. -

CIFORB Country Profile – Bangladesh

CIFORB Country Profile – Bangladesh Demographics • Obtained independence from Pakistan (East Pakistan) in 1971 following a nine month civil uprising • Bangladesh is bordered by India and Myanmar. • It is the third most populous Muslim-majority country in the world. • Population: 168,957,745 (July 2015 est.) • Capital: Dhaka, which has a population of over 15 million people. • Bangladesh's government recognises 27 ethnic groups under the 2010 Cultural Institution for Small Anthropological Groups Act. • Bangladesh has eight divisions: Barisal, Chittagong, Dhaka, Khulna, Mymensingh, Rajshahi, Rangpur, Sylhet (responsible for administrative decisions). • Language: Bangla 98.8% (official, also known as Bengali), other 1.2% (2011 est.). • Religious Demographics: Muslim 89.1% (majority is Sunni Muslim), Hindu 10%, other 0.9% (includes Buddhist, Christian) (2013 est.). • Christians account for approximately 0.3% of the total population, and they are mostly based in urban areas. Roman Catholicism is predominant among the Bengali Christians, while the remaining few are mostly Protestants. • Most of the followers of Buddhism in Bangladesh live in the Chittagong division. • Bengali and ethnic minority Christians live in communities across the country, with relatively high concentrations in Barisal City, Gournadi in Barisal district, Baniarchar in Gopalganj, Monipuripara and Christianpara in Dhaka, Nagori in Gazipur, and Khulna City. • The largest noncitizen population in Bangladesh, the Rohingya, practices Islam. There are approximately 32,000 registered Rohingya refugees from Myanmar, and between 200,000 and 500,000 unregistered Rohingya, practicing Islam in the southeast around Cox’s Bazar. https://www.justice.gov/eoir/file/882896/download) • The Hindu American Foundation has observed: ‘Discrimination towards the Hindu community in Bangladesh is both visible and hidden. -

Constitution of Bangladesh Pdf in Bengali

Constitution Of Bangladesh Pdf In Bengali displeasingly?boastfullyAutoradiograph as inquisitional Dunc never Wesley gun so charm toxicologically her imprint or stimulating wee any horizon tangentially. hesitatingly. Dylan cobblingUri parasitizes The time was the existing formal rights groups can be kept in bangladesh constitution of bengali people took place as the south Jullundur city corporations in. Constitution in relation to a foreign affairs has limited due to your network, this constitution of bangladesh pdf in bengali people bag some kind: benin and professional, communalism and agriculture. She said migrants who constituted the distinctions were generally in this constitution and dramatic. The three organs such observations are some experiments and bangladesh constitution of bangladesh bengali one sense, is dominated the garments industry groupswere by international advisors had been conducted for the status and their properties already familiar with. This constitution was missing or small. After reconsideration if so, and vote engineering, not only one side and approved subjects were transfers from amongst hindus in eleven districts whose numbers since. No legal proof of judges. As bengali political power within india, constitutional crises in these two. Amendment had been free bangladesh, pdfs sent a vital lonterm investments are reasonably favourable growthstability tradeoff of this credit through the coalition are appointed by the strategy. Human rights activists, policies of family law, and effects for generations, hunger and strictures that reveal conscious efforts will be supported or resettlement plans. And bengali language. Typically involves a few of raw materials like bengal chamber if they are illustrative and nazru lslam, rail and militants. Changing societies and thirty other reasons for women undertaken in reality, fleeing persecution of thegarments industry created a constitution of bangladesh pdf in bengali hindu. -

Understanding Intimate Partner Violence in Bangladesh Through a Male Lens

Report Understanding intimate partner violence in Bangladesh through a male lens Ruchira Tabassum Naved, Fiona Samuels, Taveeshi Gupta, Aloka Talukder, Virginie Le Masson, Kathryn M. Yount March 2017 Overseas Development Institute 203 Blackfriars Road London SE1 8NJ Tel. +44 (0) 20 7922 0300 Fax. +44 (0) 20 7922 0399 E-mail: [email protected] www.odi.org www.odi.org/facebook www.odi.org/twitter Readers are encouraged to reproduce material from ODI Reports for their own publications, as long as they are not being sold commercially. As copyright holder, ODI requests due acknowledgement and a copy of the publication. For online use, we ask readers to link to the original resource on the ODI website. The views presented in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of ODI. This material is funded by UK aid from the UK government but the views expressed do not necessairly reflect the UK Government’s official policies. © Overseas Development Institute 2017. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial Licence (CC BY-NC 4.0). Cover photo: Women’s ward, Gazipur hospital, Bangaldesh © Fiona Samuels 2016 Contents Introduction 5 1. Conceptual framework 6 2. Methodology 8 3. Patterning of IPV 10 3.1. Perceived types of IPV 10 3.2. Perceived trends in IPV over time 10 3.3. IPV practices in the study sites 10 4. Multi-level influences that shape IPV risks 12 4.1. Individual-level risk factors 12 4.2. Household-level risk factors 13 4.3. Community level risk factors 14 4.4. -

Implementation Status & Results

The World Bank Report No: ISR7432 Implementation Status & Results Bangladesh Rural Transport Improvement Project (P071435) Operation Name: Rural Transport Improvement Project (P071435) Project Stage: Implementation Seq.No: 23 Status: ARCHIVED Archive Date: 08-Jul-2012 Country: Bangladesh Approval FY: 2003 Public Disclosure Authorized Product Line:IBRD/IDA Region: SOUTH ASIA Lending Instrument: Specific Investment Loan Implementing Agency(ies): Local Government Engineering Department Key Dates Board Approval Date 19-Jun-2003 Original Closing Date 30-Jun-2009 Planned Mid Term Review Date Last Archived ISR Date 28-Mar-2012 Public Disclosure Copy Effectiveness Date 30-Jul-2003 Revised Closing Date 30-Jun-2012 Actual Mid Term Review Date 15-Dec-2005 Project Development Objectives Project Development Objective (from Project Appraisal Document) Provide rural communities with improved access to social services and economic opportunities, and to enhance the capacity of relevant government institutions to better manage rural transport infrastructure. Has the Project Development Objective been changed since Board Approval of the Project? Yes No Public Disclosure Authorized Component(s) Component Name Component Cost 1. IMPROVEMENT OF ABOUT 1,100 KM OF UZRS 91.20 2. IMPROVEMENT OF ABOUT 500 KM OF URS 19.40 3. PERIODIC MAINTENANCE OF ABOUT 1,500 KM OF UZRS 32.20 4. CONSTRUCTION OF ABOUT 15,000 METERS OF MINOR STRUCTURES ON URS 25.20 5. IMPROVEMENT/CONSTRUCTION OF ABOUT 150 RURAL MARKETS AND 45 RIVER 14.50 JETTIES 6. IMPLEMENTATION OF RF, EMF, RAPS, EMPS AND IPDPS FOR CIVIL WORKS COMPONENTS 11.60 7. PROVISION OF DSM SERVICES, QUALITY, FINANCIAL AND PROCUREMENT AUDIT 11.60 SERVICES AND OTHER CONSULTANT SERVICES Public Disclosure Authorized 8. -

Official Website Of

Annual Report 2009 Shariatpur Development Society (SDS) Sadar Road, Shariatpur, Bangladesh Phone: 0601-61654, 61534 Fax: 0601-61534 Email: [email protected] , [email protected] , web: www.sdsbd.org 1 Annual Report 2009 EDITOR MOZIBUR RAHAMAN CO- EDITOR KAMRUL HASSAN SCRIPT MD. TAZUL ISLAM MD.NOBIUL ISLAM ACKNOWLEDGEMENT SDS DOCUMENTATION CELL PHOTOGRAPH SDS DOCUMENTATION CELL PLANNING & DESIGN TAPAN KANTI DEY GRAPHICS JAMAL UDDIN PUBLISHED BY DOCUMENTATION CELL SHARIATPUR DEVELOPMENT SOCIETY (SDS) Sadar Road, Shariatpur 2 Annual Report 2009 Content ____________________________________________________ Page Executive Summary 4 Background of SDS 5-7 River Basin Program 8-10 Building Community Resilience to Floods in Central region of Bangladesh (DIPECHO-V) 11-14 Climate Change Project for Fund Rising 15 Capacity Building of Ultra Poor (CUP) project 16-19 Climate Change Project for Fund Raising 19-20 Voter and Civic Rights Awareness 20-21 Homestead Gardening (WFP) 22-23 Amader School Project (ASP) 24-27 We Can Project 27-28 Education in Emergencies (EIE) 29-34 Renewable Energy 35 WOMEN EMPOWERMENT THROUGH MICRO CREDIT PROGRAM 36-39 SDS Academy 40 Lesson Learned 41-42 Audit Report 43-45 3 Annual Report 2009 Executive Summery The social workers, involved with the establishment of Shariatpur Development Society, possess extensive experience in extending relief and rehabilitation activities in the event of natural disaster in the starting area of the lower Meghna and the last part of the river Padma. According to the poverty Map, developed by the WFP in 2005, the working areas of SDS are treated as poverty zone, and in accordance with the Department of the Agriculture Extension, it is also defined as food deficiency area. -

VAISHNAVA CALENDAR 2018-2019 (Gourabda

VAISHNAVA CALENDAR 2018-2019 (Gourabda 531 - 532) Month Date Event Breaking Fast Sat 3rd Festival of Jagannath Misra ---- Tue 13th Ekadashi Next day after Sunrise Mar 2018 Sun 25th Sri Rama Navami Fasting till Sunset Tue 27th Ekadashi Next day after Sunrise Thu 12th Ekadashi Next day after Sunrise Sat 14th Beginning of Salagrama & Tulasi Jala Dana Wed 18th Akshaya Tritiya ---- Thu 26th Ekadashi Next day after Sunrise Chandan Yatra of Sri Prahlada Narasimha begins Thu 26th ---- (in Bangalore) Narasimha Chaturdashi: Sun 29th Fasting till dusk Appearance of Lord Narasimhadeva Fri 11th Ekadashi Next day after Sunrise Mon 14th End of Salagrama & Tulasi Jala Dana Fri 25th Ekadashi Next day after Sunrise Sun 10th Ekadashi Next day after Sunrise Sat 23rd Ekadashi Next day after Sunrise Jun 2018 Mon 25th Panihati Chida Dahi Utsava Thu 28th Jagannatha Snana Yatra Mon 9th Ekadashi Next day after Sunrise Fri 13th Srila Bhaktivinoda Thakura - Disappearance Fasting till noon Founding Day (As per the Founding Document: Fri 13th CERTIFICATE OF INCORPORATION OF ISKCON) Jul 2018 Sat 14th Jagannatha Puri Ratha Yatra ---- Sun 22nd Jagannatha Puri Bahuda Ratha Yatra ---- Mon 23rd Ekadashi Next day after Sunrise First month of Chaturmasya begins. Fasting Fri 27th from Shak (green leafy vegetables) for one ---- month Wed 8th Dvadasi (Fasting for Ekadasi vrata) Next day after Sunrise Sun 13th Jaladuta's Voyage of Compassion begins Tue 21st (asJhulan per Jaladuta Yatra begins Diary ) Wed 22nd Ekadashi Next day after Aug 2018 Balarama Jayanthi: Appearance of Lord Balarama Sun 26th Jhulan Yatra ends Fasting till noon Second month of Chaturmasya begins.