Fighting HIV with Juggling Clubs an Introduction to Ethiopia’S Circuses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8 Places to Run Away with the Circus

chicagoparent.com http://www.chicagoparent.com/magazines/going-places/2016-spring/circus 8 places to run away with the circus The Actors Gymnasium Run away with the circus without leaving Chicago! If your child prefers to hang upside down while swinging from the monkey bars or tries to jump off a kitchen cabinet to reach the kitchen fan, he belongs in the circus. He’ll be able to squeeze out every last ounce of that energy, and it’s the one place where jumping, swinging, swirling and balancing on one foot is encouraged. Here are some fabulous places where your child can juggle, balance and hang upside down. MSA & Circus Arts 1934 N. Campbell Ave., Chicago; (773) 687-8840 Ages: 3 and up What it offers: Learn skills such as juggling, clowning, rolling globe, sports acrobatics, trampoline, stilts, unicycle 1/4 and stage presentation. The founder of the circus arts program, Nourbol Meirmanov, is a graduate of the Moscow State Circus school, and has recruited trained circus performers and teachers to work here. Price starts: $210 for an eight-week class. The Actors Gymnasium 927 Noyes St., Evanston; (847) 328-2795 Ages: 3 through adult (their oldest student at the moment is 76) What it offers: Kids can try everything from gymnastics-based circus classes to the real thing: stilt walking, juggling, trapeze, Spanish web, lyra, contortion and silk knot. Classes are taught by teachers who graduated from theater, musical theater and circus schools. They also offer programs for kids with disabilities and special needs. Price starts: $165 for an 8-10 week class. -

National Circus and Acrobats of the People's Republic of China

Friday, September 11, 2015, 8pm Saturday, September 12, 2015, 2pm & 8pm Zellerbach Hall National Circus and Acrobats of the People’s Republic of China Peking Dreams Cal Performances’ $"#%–$"#& season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. PROGRAM Peking Dreams EKING (known today as Beijing), the capital of the People’s Republic of China, is a Pfamous historical and cultural city with a history spanning 1,000 years and a wealth of precious Chinese cultural heritage, including the Great Wall, the Forbidden City, the Summer Palace, and the Temple of Heaven. Acrobatic art, Chinese circus, and Peking opera are Chinese cultural treasures and are beloved among the people of Peking. These art forms combine music, acrobatics, performance, mime, and dance and share many similarities with Western culture. Foreign tourists walking along the streets or strolling through the parks of Peking can often hear natives sing beautiful Peking opera, see them play diabolo or perform other acrobatics. Peking Dreams , incorporating elements of acrobatics, Chinese circus, and Peking opera, invites audiences into an artistic world full of history and wonder. The actors’ flawless performance, colorful costumes, and elaborate makeup will astound audiences with visual and aural treats. PROGRAM Opening Acrobatic Master and His Pupils The Peking courtyard is bathed in bright moonlight. In the dim light of the training room, three children formally become pupils to an acrobatic master. Through patient teaching, the master is determined to pass his art and tradition down to his pupils. The Drunken Beauty Amidst hundreds of flowers in bloom, the imperial concubine in the Forbidden City admires the full moon while drinking and toasting. -

Spring 2016 Circus Harmony Classes Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday Fees: the Following Classes Are $175

Spring 2016 Circus Harmony Classes Spring 2016 Session Details Circus Harmony Winter Break Classes th rd (at City Museum 701 N. 15th, 3rd flr., St. Louis, 63103) Monday, February 1 – Sunday, May 15, 2016 (at City Museum 701 N. 15 , 3 flr., St. Louis, 63103) Monday (NO Class Sunday, March 27, 2016) 10:00–11:00 AM Preschool Circus (ages 3-5) Culmination Shows will be held: Learn a variety of circus arts including balancing, 1:00-2:30 PM Homeschool Circus Arts May 13, 14, 15, 2016 (times to be announced) acrobatics, object manipulation, aerial and more! 4:30-6:00 PM Intermediate Mini-trampoline & Sign up for morning, afternoon, or both! Tumbling (must have back handspring) Register at www.circusharmony.org December 21, 22, 23, 24 6:00-7:30 PM Youth Combo Aerial w/Copper Youth Classes for ages 5-17 Circus Arts Level 1.5 & 2 need instructor permission Session 1 A: 9:00 AM – 12:00 PM Tuesday Session 11 B: 1:00 PM – 4:00 PM 6:30-8:00 PM Adult Combo Aerial w/Copper Fees: December 28, 29, 30, 31 The following classes are $175: Session 2A: 9:00 AM – 12:00 PM Session 2B: 1:00 PM – 4:00 PM Wednesday Preschool Circus 4:30-5:30 PM Hula Hoops Intro to Circus Arts Cost $90 per session 4:30-5:30 PM Beginning Tumbling (ages 7-14) Tumbling 5:30-7:00 PM Balancing (wire, globe, unicycle,stilts, rolla) Hula Hoops Juggling & Unicycling Clubs 7:00-8:30 PM Adult Basic Circus Arts Juggling Club All ages & skill levels welcome to join! Unicycle Club Friday Winter Break Juggling Club: Thursday The following classes are $250 Classes held Fridays 6:00 – 7:00 PM Dates: -

CV Zoe Marshall

CIRRICULUM VITAE Zoë Marshall – Circus Artist ABN: 41 793 810 275 Name: Zoë Marshall Nationality: Australian Born: Australia Speaks: English, basic French Height: 163cm Weight: 57kg Passports: -Australian -British Contact Email: [email protected] Phone: UK: +44 539 217 125 AU+61 458 279 905 Instagram: zoe.marshall.circus Website: zoe-marshall.com “..something out of the ordinary..” “Marshall’s performance was completely beautiful, and showcased both her poise and unique skill” Skills: • Hair Hanging • Chinese Contortion Carpet-Spinning – Including Marinelli stand (Mouth balancing) • Tumbling (Level 8/10 gymnastics) • Dance (Contemporary, commercial, salsa/bachata +) • Aerial Hoop • Group Acrobatics (fly/middle/base) • Basic Head-balancing • Basic Pass juggling (Clubs, balls) Performance Experience: • 2019/20: La Clique, Underbelly UK Christmas tour (London, Leicester Square) • 2019: Circus OZ, Colombia tour “Model Citizens” • 2019: Strut & Fret - Deluxe DELUXE (Hobart, Wollongong, Newcastle) • 2018/19: Circus OZ/The 7 Fingers - "Fibonacci Project” (Rob Tannion/Samual Tétreault) • 2018/19: “Matador” Burlesque/dance/circus for Bass Fam Creative (Melbourne, Sydney Opera house, Adelaide, Brisbane) • 2018: Stunt Role in the Movie Production of “The Whistleblower” • 2018: Solos for MJC Gala show, NYX Cosmetics Make-up competition • 2018: Stand Here by Tons of Sense, Testing Grounds - Melbourne. • 2017/18: Season of “Spectrum” with Uncovered Circus for MIDSUMMA 2018 • 2017: Season for Director Priscilla Jackman’s “Eurydike + Orpheus”, -

The Beginner's Guide to Circus and Street Theatre

The Beginner’s Guide to Circus and Street Theatre www.premierecircus.com Circus Terms Aerial: acts which take place on apparatus which hang from above, such as silks, trapeze, Spanish web, corde lisse, and aerial hoop. Trapeze- An aerial apparatus with a bar, Silks or Tissu- The artist suspended by ropes. Our climbs, wraps, rotates and double static trapeze acts drops within a piece of involve two performers on fabric that is draped from the one trapeze, in which the ceiling, exhibiting pure they perform a wide strength and grace with a range of movements good measure of dramatic including balances, drops, twists and falls. hangs and strength and flexibility manoeuvres on the trapeze bar and in the ropes supporting the trapeze. Spanish web/ Web- An aerialist is suspended high above on Corde Lisse- Literally a single rope, meaning “Smooth Rope”, while spinning Corde Lisse is a single at high speed length of rope hanging from ankle or from above, which the wrist. This aerialist wraps around extreme act is their body to hang, drop dynamic and and slide. mesmerising. The rope is spun by another person, who remains on the ground holding the bottom of the rope. Rigging- A system for hanging aerial equipment. REMEMBER Aerial Hoop- An elegant you will need a strong fixed aerial display where the point (minimum ½ ton safe performer twists weight bearing load per rigging themselves in, on, under point) for aerial artists to rig from and around a steel hoop if they are performing indoors: or ring suspended from the height varies according to the ceiling, usually about apparatus. -

Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Cloud

Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Cloud Swing 1000-01 2:30-3:00PM Swinging Trapeze 1000-01 2:00-3:00PM Hammock 0200-02 3:00-3:30PM Double Trapeze 0100-04 3:30-4:15PM Swinging Trapeze 1000-02 2:45-3:30PM 9:00 AM Wings 0000-01 2:30-3:45PM Pas de Deux 0000-01 3:00-4:00PM Revolving Ladder 1000-01 3:15-4:00PM Handstands 1000-01 3:30-4:15PM 4-Girl Spinning Cube 0000-01 3:15-4:00PM Flying Trapeze 0000-02 3:00 PM Swinging Trapeze 1000-02 2:45-3:30PM Double Trapeze 0100-02 3:15-4:00PM Swinging Trapeze 0100-02 3:15-4:00PM Chair Stacking 1000-01 Duo Trapeze 0100-01 3:15-4:00PM Globes 0000-01 Swinging Trapeze 0100-01 3:30-4:15PM Duo Trapeze 0100-02 3:30-4:15PM Double Trapeze 0100-04 3:30-4:00PM Static Trapeze 1000-01 Triangle Trapeze 0100-02 3:15-4:00PM Low Casting Fun 0000-04 4-Girl Spinning Cube 1000-01 3:45-4:30PM Handstands 1000-01 Triangle Trapeze 1000-01 3:30-4:15PM Duo Trapeze 0100-03 3:30-4:15PM Mini Hammock 0000-02 High Wire 1000-01 Manipulation Cube 0000-01 3:30-4:00PM Star 0100-01 Pas de Deux 0100-01 Toddlers 0200-03 ages 3-4 Swinging Trapeze 0100-01 3:30-4:15PM Acrobatics 0205-01 ages 10+ Triangle Trapeze 1000-01 3:30-4:15PM Double Trapeze 0100-04 3:30-4:15PM Duo Hoops 1000-01 4:00-4:30PM Trampoline 0000-04 ages 6-9 4-Girl Spinning Cube 1000-01 3:45-4:30PM Bungee Trapeze 0300-01 Cloud Swing 0100-02 4:00-4:30PM Handstands 1000-01 3:30-4:15PM Swinging Trapeze 1000-01 4:15-5:00PM 4:00 PM Swinging Trapeze 0000-01 4:15-5:00PM Girls' Master Intensive 0000-01 Pas de Deux 0000-01 4:15-5:15PM Manipulation Cube 0000-01 4:15-5:00PM -

BRIO Youth Training Company (Ages 8-18) September 2020 - June 2021

BRIO Youth Training Company (ages 8-18) September 2020 - June 2021 1 Brio Program Overview About Brio The Brio Youth Training Company is a ten-month developmental program preparing young circus artists to pursue the joy and wonder of circus with greater intensity. Brio company members will have the opportunity to work with professional performers and world-class instructors to build skills and explore the limitless world of circus arts. Our overarching goal is to facilitate the development of circus skills, creativity, and professionalism, at an appropriate level for the development of our students within a program that is engaging, challenging, growth-oriented, and fun. The structure is designed to be clear— with three levels of intensity—yet flexible enough to respond to individuals’ needs. Candidates should have a background in movement disciplines such as dance, gymnastics, martial arts, parkour, diving, or ice skating, and a desire to bring their passion for the circus arts to the next level. Ideal Brio company members are ages 8 to 18 and interested in exploring the possibilities of circus arts; members may be looking forward towards next steps in our Elements adult training company or circus college, or may just be excited to work with a community of creative and dedicated young artists! The program is currently designed to adjust to the safest training environment, whether online only, hybrid online and small in-studio lessons, or full in-studio classes; see program details below for further information. Training Levels: Junior Core Training Program Students age 8-10 have the option of Brio Junior Core, an introductory program with a lower time commitment than the traditional Core training program. -

Animal-Free Circuses Animal-Free Circuses Are Growing in Popularity

Animal-Free Circuses Animal-free circuses are growing in popularity. Whether you’re looking for dazzling and humane family entertainment, a circus to perform at a fair, or a circus to sponsor for a fundraiser, these circuses feature only skilled human performers. CIRCUS TOUR FUNDRAISERS DESCRIPTION Audience members become a part of the Big Top out the Box Circus North America No experience and get a chance to interact with 1-844-542-4728 characters in the show. [email protected] This is a vaudeville-like show that performs Bindlestiff Family Cirkus U.S., Canada, No mostly at festivals and other events and offers P.O. Box 386 and Europe in workshops and exhibitions to schools and New York, NY 10009 the spring and universities. 718-963-2918 summer 1-877-BINDLES [email protected] bindlestiff.org Sensational puppetry puts “elephants” in the ring as Circus 1903 Currently at the No never before seen, along with a huge cast in the most 310-859-4478 Paris Theater at [email protected] Paris Las Vegas unique circus acts from around the world—from International inquiries: strongmen to contortionists and acrobats to [email protected] musicians, knife throwers, high-wire walkers, and much more. Circus Center The San Francisco Yes This center offers an exquisitely choreographed 755 Frederick St. Bay Area adventure in acrobatics, aerial work, dance, and San Francisco, CA 94117 clowning that relies on grit, not glitz, to get its magic 415-759-8123 across. It gives scholarships to low-income children to [email protected] attend its annual circus camp and distributes free circuscenter.org tickets to nonprofit organizations. -

Dust Palace Roving and Installation Price List 2017

ROVING AND INSTALLATION CIRQUE ENTERTAINMENT HAND BALANCE AND CONTORTION One of our most common performance installations is Hand Balance Contortion. Beautiful and graceful this incredible art is mastered by very few, highly skilled performers. Roving or installation spots are only possible for 30 mins at a time and are priced at $950+gst per performer. ADAGIO AND ACROBATICS Adagio, hand to hand, balance acrobatics and trio acro are all ways to describe the art of balancing people on people. Usually performed as a couple this is the same as hand balance contortion in that it’s only possible for 30 minute stints. Roving or installation can be performed in any style and we’re always happy to incorporate your events theme or branding into the theatrics around the skill. Performers are valued at $950+gst per 30 minute slot. MANIPULATION SKILLS Manipulation skills include; Hula Hoops, Juggling, Cigar boxes, Diabolo, Chin Balancing, Poi Twirling, Plate Spinning and Crystal Ball. As a roving or installation act these are fun and lively, bringing some nice speedy movement to the room. All are priced by the ‘performance hour’ which includes 15 minutes break and range between $400+gst and $700+gst depending on the performer and the skill. Some performers are capable of character work and audience interaction. Working these skills in synchronisation with multiple performers is a super cool look. Most of these skills can be performed with LED props. EQUILIBRISTICS aka balance skills The art of balancing on things takes many long hours of dedication to achieve even the most basic result. -

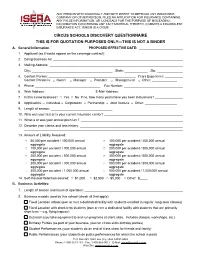

Circus Schools Discovery Questionnaire This Is for Quotation Purposes Only—This Is Not a Binder A

ANY PERSON WHO KNOWINGLY AND WITH INTENT TO DEFRAUD ANY INSURANCE COMPANY OR OTHER PERSON, FILES AN APPLICATION FOR INSURANCE CONTAINING ANY FALSE INFORMATION, OR CONCEALS FOR THE PURPOSE OF MISLEADING, INFORMATION CONCERNING ANY FACT MATERIAL THERETO, COMMITS A FRAUDULENT INSURANCE ACT, WHICH IS A CRIME. CIRCUS SCHOOLS DISCOVERY QUESTIONNAIRE THIS IS FOR QUOTATION PURPOSES ONLY—THIS IS NOT A BINDER A. General Information PROPOSED EFFECTIVE DATE: 1. Applicant (as it would appear on the coverage contract): 2. Doing Business As: 3. Mailing Address: City: State: Zip: 4. Contact Person: Years Experience: Contact Person is: □ Owner □ Manager □ Promoter □ Management □ Other: 5. Phone: Fax Number: 6. Web Address: E-Mail Address: 7. Is this a new business? □ Yes □ No If no, how many years have you been in business? 8. Applicant is: □ Individual □ Corporation □ Partnership □ Joint Venture □ Other: 9. Length of season: 10. Who was your last or is your current insurance carrier? 11. What is or was your annual premium? 12. Describe your claims and loss history: 13. Amount of Liability Required: □ 50,000 per accident / 100,000 annual □ 100,000 per accident / 200,000 annual aggregate aggregate □ 100,000 per accident / 300,000 annual □ 200,000 per accident / 300,000 annual aggregate aggregate □ 200,000 per accident / 500,000 annual □ 300,000 per accident / 500,000 annual aggregate aggregate □ 300,000 per accident / 300,000 annual □ 500,000 per accident / 500,000 annual aggregate aggregate □ 300,000 per accident / 1,000,000 annual □ 500,000 per accident / 1,000,000 annual aggregate aggregate 14. Self-Insured Retention desired: □ $1,000 □ $2,500 □ $5,000 □ Other: $ B. -

Super Novas 2019 – 2020 Registration Packet

Super Novas 2019 – 2020 Registration Packet Overview of Circus Center’s Pre-Professional Youth Program Circus Center’s Pre-Professional Youth Program is a yearlong training program. Students are asked to commit to the entire year. The program is open to students ages 7–18 (exceptions for skilled younger students may be made). Students build a solid foundation in the basic skills of circus, including strength, flexibility, balance and coordination. Our Pre- Professional Youth Program has three levels: Rising Stars, Super Novas, and the San Francisco Youth Circus. For those students who want it and work for it, Circus Center’s Pre-Professional Youth Program has a long history of preparing young people for elite training and careers in the circus. Even for students who do not pursue a career in the circus, the exposure to high-level training builds discipline, commitment, and confidence that will serve them well in any path they choose. Super Novas (ages 9-16) – Students deepen their circus training when they advance to Super Novas. They continue to develop their strength, flexibility, and coordination while advancing their circus skills. Super Novas focus on two specialties throughout the year which are chosen by the students with coach approval. All Super Novas continue to train tumbling, group acrobatics, and juggling as well. The Super Novas develop their performance skills through weekly dance and acting classes. ● Students are required to complete 80 hours of training over the summer to prepare for the school year ● From September-May, -

Acrobatics Acts, Continued

Spring Circus Session Juventas Guide 2019 A nonprofit, 501(c)3 performing arts circus school for youth dedicated to inspiring artistry and self-confidence through a multicultural circus arts experience www.circusjuventas.org Current Announcements Upcoming Visiting Artists This February, we have THREE visiting artists coming to the big top. During the week of February 4, hip hop dancer and choreographer Bosco will be returning for the second year to choreograph the Teeterboard 0200 spring show performance along with a fun scene for this summer's upcoming production. Also arriving that week will be flying trapeze expert Rob Dawson, who will attend all flying trapeze classes along with holding workshops the following week. Finally, during our session break in February, ESAC Brussels instructor Roman Fedin will be here running Hoops, Mexican Cloud Swing, Silks, Static, Swinging Trapeze, Triple Trapeze, and Spanish Web workshops for our intermediate-advanced level students. Read more about these visiting artists below: BOSCO Bosco is an internationally renowned hip hop dancer, instructor, and choreographer with over fifteen years of experience in the performance industry. His credits include P!nk, Missy Elliott, Chris Brown, 50 Cent, So You Think You Can Dance, The Voice, American Idol, Shake It Up, and the MTV Movie Awards. Through Bosco Dance Tour, he’s had the privilege of teaching at over 170 wonderful schools & studios. In addition to dance, he is constantly creating new items for BDT Clothing, and he loves honing his photo & video skills through Look Fly Productions. Bosco choreographed scenes in STEAM and is returning for his 2nd year choreographing spring and summer show scenes! ROB DAWSON As an aerial choreographer, acrobatic equipment designer, and renowned rigger, Rob Dawson has worked with entertainment companies such as Cirque du Soleil, Universal Studios, and Sea World.