Geoffrey Tyack, 'Longner Hall', the Georgian Group Journal, Vol. Xiv

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Autumn 2018 Newsletter

Shropshire National Trust Social and Supporter Group Newsletter Autumn 2018 Issue 92 !2 SHROPSHIRE NATIONAL TRUST CENTRE PRESIDENT: Mr David R Brown OFFICERS: Chairman: Miss Thelma Foster Hon Secretary: Mrs Pat Matthews Hon Treasurer: Mrs Gillian Davey COMMITTEE: Walks Coordinator: Mrs Carol Danby Programme Secretary: Mrs Isobel Parfitt Newsletter Editor: Maureen Formby Membership Secretary: Marjorie Farnsworth Vice Chairman and Website: Mr Les Jones Events coordinator: Alison Bates Are you willing to receive your newsletter by email? If so please send an email to [email protected] giving your name and address. This will save postage costs and leave more funds for us to donate to National Trust properties locally. Email will also be used to keep you up-to-date with outings, walks and events extra to the programme. Your details will not be passed on to any other organisation. !3 Book now! For Thursday 27 September 2018 There is a trip to Weaver Hall Museum and Workhouse & Metropolitan Cathedral Liverpool email: Pat Matthews [email protected] CONTENTS OF NEWSLETTER Page 2 List of officers Page 4 Chairman's Notes and Treasurer's Report Page 5 Thursday 27 September 2018 - Outing to Weaver Hall Museum and Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral Page 6/7 Report on Trysull Walk – 22nd June Shropshire NT Walking Group – End of an Era Page 8 18 October 2018 Walk - Treasure Hunt - Much Wenlock Page 9 Report on visit to the Fishpool Restoration Project at Croft Castle on 28 June Page 10 Thursday 29 November 2018 – Christmas Outing to Worcester Victorian Christmas Fayre Page 11 Attingham Park Trailer Refurbishment Page 12 Holiday 2019 – The History, Gardens and Heritage Houses of Sussex Page 13 Enquiry form for the Sussex holiday Report on Wilderhope Walk - 17 July 2018 Page 14 Summary of events – talks and outings for 2018/19 Pages 15/16 General information and your membership card !4 CHAIRMAN’S NOTES JULY 2018 We start a new season with opportunities to change some of our methods of working and communication. -

Shropshire and Telford & Wrekin

Interactive PDF Document Look for the pointer symbol for document links. • The Contents page has links to the relevant items. • The titles on the Chapters, Plans and Tables all link back to the Contents page. • Further interactive links are provided to aid your navigation through this document. Shropshire,Telford & Wrekin Minerals Local Plan 1996 - 2006 Adopted Plan April 2000 SHROPSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL AND TELFORD & WREKIN COUNCIL SHROPSHIRE, TELFORD & WREKIN Minerals Local Plan 1996 to 2006 (Adopted Plan - April 2000) Carolyn Downs Sheila Healy Corporate Director: Corporate Director: Community & Environment Services Environment & Economy Community & Environment Services Environment & Economy Shropshire County Council Telford & Wrekin Council The Shirehall, Abbey Foregate Civic Offices, PO Box 212 Shrewsbury, Shropshire Telford, Shropshire SY2 6ND TF3 4LB If you wish to discuss the Plan, please contact Adrian Cooper on (01743) 252568 or David Coxill on (01952) 202188 Alternatively, fax your message on 01743 - 252505 or 01952 - 291692 i. Shropshire,Telford & Wrekin Minerals Local Plan 1996 - 2006 Adopted Plan April 2000 access to information... This Plan can be made available on request in large print, Braille or audio cassette. It may take us some days to prepare a copy of the document in these formats. If you would like a copy of the Plan in one of the above formats, please contact Adrian Cooper on (01743) 252568, or write to: Community & Environment Services Shropshire County Council The Shirehall Abbey Foregate Shrewsbury SY2 6ND You can fax us on (01743) 252505. You can contact us by e-mail on: [email protected] This Plan is also available on our websites at: http:/shropshire-cc.gov.uk/ and: http:/telford.gov.uk/ ii. -

Rural Settlement List 2014

National Non Domestic Rates RURAL SETTLEMENT LIST 2014 1 1. Background Legislation With effect from 1st April 1998, the Local Government Finance and Rating Act 1997 introduced a scheme of mandatory rate relief for certain kinds of hereditament situated in ‘rural settlements’. A ‘rural settlement’ is defined as a settlement that has a population of not more than 3,000 on 31st December immediately before the chargeable year in question. The Non-Domestic Rating (Rural Settlements) (England) (Amendment) Order 2009 (S.I. 2009/3176) prescribes the following hereditaments as being eligible with effect from 1st April 2010:- Sole food shop within a rural settlement and has a RV of less than £8,500; Sole general store within a rural settlement and has a RV of less than £8,500; Sole post office within a rural settlement and has a RV of less than £8,500; Sole public house within a rural settlement and has a RV of less than £12,500; Sole petrol filling station within a rural settlement and has a RV of less than £12,500; Section 47 of the Local Government Finance Act 1988 provides that a billing authority may grant discretionary relief for hereditaments to which mandatory relief applies, and additionally to any hereditament within a rural settlement which is used for purposes which are of benefit to the local community. Sections 42A and 42B of Schedule 1 of the Local Government and Rating Act 1997 dictate that each Billing Authority must prepare and maintain a Rural Settlement List, which is to identify any settlements which:- a) Are wholly or partly within the authority’s area; b) Appear to have a population of not more than 3,000 on 31st December immediately before the chargeable financial year in question; and c) Are, in that financial year, wholly or partly, within an area designated for the purpose. -

SHROPSHIRE. (&ELLY's Widows, Being the Interest of £Roo

~54 TUGFORD,.. SHROPSHIRE. (&ELLY's widows, being the interest of £roo. Captain Charles Bald- Office), via Munslow. The nearest money order offices wyn Childe J.P. of Kinlet Hall is lord m the manor of the are at Munslow & Church Stretton & telegraph office at entire parish and sole landowner. The soil is red clay; the Church Stretton. WALL LETTER Box in Rectory wall, subsoil varies from sandstone to gravel. The chief crops cleared at 3,40 p.m. week days only are wheat, barley, oats and turnips. The acreage is 1,312; CARRIER.-Maddox, from Bauldon, passes through to Lud- rateable value, £1,461 ; the population in 1881 was no, low on mon. & Bridgnorth on sat BAUCOT is a township I mile west. Parish Clerk, Samuel Jones. The children of this parish attend the schools at Munslow & Letters are received through Craven .Arms (Railway Sub- Abdon Farmer Nathaniel, farmer 1 Wall George, farmer & miller (water) Tugford. Gwilt Thomas, farmer Woodhoose Rev. Richard B.A. Rectory Jones Saml. blacksmith&; parish clerk Baucot.. Dodson William, wheelwright, Balaam's Morris John, farmer Marsh Thomas, farmer & overseer heath Price William, shopkeeper ShirleyJane (Mrs.)&; Richd.Wm.farmrs UFFINGTON is a parish and village, pleasantly seated canopies, and a timber ceiling of the 14th century: the 3 miles east from Shrewsbury and 2! miles north-west from most perfect portion now left is the infirmary hall, with a Upton Magna station on the Great Western and London and turreted western gable on the south side of the base court; North Western joint line from Shrewsbury -

Glenbank House

WROXETER & UPPINGTON PARISH COUNCIL MINUTES OF COUNCIL MEETING HELD ON 14TH MARCH 2016 AT 7.30PM AT THE WROXETER HOTEL, WROXETER PRESENT: Chairman –B. Nelson (BN), J. Davies (JD), L. Davies (LD), P. Davies (PD), M. Millington (MM), S. Rowlands (SR), I. Sherwood (IS) Clerk: Mrs R. Turner In attendance: Shropshire Councillor Claire Wild, 4 members of the public 076/1516 PUBLIC SESSION A member of the public spoke in relation to his complaint against the parish council. The Chairman invited other members of the public to speak; no-one wished to speak. 077/1516 APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE Received and accepted from Cllr. Amos. 078/1516 DISCLOSABLE PECUNIARY INTERESTS & DISPENSATION REQUESTS None declared. 079/1516 REPORTS Cllr. Wild explained that the SC Council Tax has risen by 1.99% with a further increase of 2% for Adult Social Care costs. She supported parishes taking on minor highways maintenance as it offers good value for money. Councillors expressed concern over the practicality of taking on road surfacing repairs. She urged parish councillors to attend events relating to The Big Conversation and to read the Shropshire Council Financial Strategy which went to Cabinet in January 2016. The police had reported the following crimes from December 2015 to February 2016: Assault: 0 Theft: 0 Burglary Other: 0 Vehicle Crime: 0 Criminal Damage: 1 Burglary Dwelling: 0 Other: 0 Road Traffic Incident: 0 Road Collision: 2 ASB Personal: 0 ASB Environmental: 0 ASB Nuisance: 0 080/1516 MINUTES OF THE COUNCIL MEETINGS HELD ON 11TH JANUARY 2016 370 Clerk: Mrs R. Turner, The Old Police House, Nesscliffe, Shrewsbury, SY4 1DB Email: [email protected] Tel: 01743 741611 Adam Beresford-Browne was incorrectly listed as a councillor, rather than a member of the public. -

About the Cycle Rides

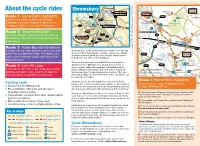

Sundorne Harlescott Route 45 Rodington About the cycle rides Shrewsbury Sundorne Mercian Way Heath Haughmond to Whitchurch START Route 1 Abbey START Route 2 START Route 1 Home Farm Highlights B5067 A49 B5067 Castlefields Somerwood Rodington Route 81 Gentle route following Route 81 through Monkmoor Uffington and Upton Magna to Home Farm, A518 Pimley Manor Haughmond B4386 Hill River Attingham. Option to extend to Rodington. Town Centre START Route 3 Uffington Roden Kingsland Withington Route 2 Around Attingham Route 44 SHREWSBURY This ride combines some places of interest in Route 32 A49 START Route 4 Sutton A458 Route 81 Shrewsbury with visits to Attingham Park and B4380 Meole Brace to Wellington A49 Home Farm. A5 Upton Magna A5 River Tern Walcot Route 3 Acton Burnell Adventure © Crown copyright and database rights 2012 Ordnance Survey 100049049 A5 A longer ride for more experienced cyclists with Shrewsbury is a very attractive historic market town nestled in a loop of the River Severn. The town centre has a largely Berwick Route 45 great views of Wenlock Edge, The Wrekin and A5064 Mercian Way You are not permitted to copy, sub-licence, distribute or sell any of this data third parties in form unaltered medieval street plan and features several timber River Severn Wharf to Coalport B4394 visits to Acton Burnell Castle and Venus Pool framed 15th and 16th century buildings. Emstrey Nature Reserve Home Farm The town was founded around 800AD and has played a B4380 significant role in British history, having been the site of A458 Attingham Park Uckington Route 4 Lyth Hill Loop many conflicts, particularly between the English and the A rewarding ride, with a few challenging climbs Welsh. -

Section One: the Context

Shropshire and Telford &Wrekin Sustainability and Transformation Plan 2016-2021 Version 5.0 Version control Date Version Notes August 2016 V1.1 Initial draft compiled from June STP December 14th 2016 V2.0 Discussion at STP Partnership Board. Prioritised actions. Timescales revised January 11th 2017 V3.3 Discussed at STP Partnership Board. Additional actions agreed January 25th V4.1 Review of updated content by work-stream leads. Further amendments agreed January 31st 2017 V5.0 Resubmitted incorporating changes and feedback from NHSE 31/01/2017 Shropshire and Telford & Wrekin Sustainability Transformation Plan 2 Coverage Geography Key Footprint Information Name of Footprint and Number: Shropshire and Telford & Wrekin (11) Midlands and East Region- NHS England Region: Shropshire and Telford & Wrekin Nominated lead for the footprint: Simon Wright, CEO Shropshire and Telford Hospitals Contact Details (email and phone): [email protected]; 01743 261 001 Organisations within the footprint: Shropshire Clinical Commissioning Group Telford & Wrekin Clinical Commissioning Group Shropshire Community Health NHS Trust The Shrewsbury and Telford Hospitals NHS Trust Robert Jones & Agnes Hunt Foundation Trust South Shropshire & Staffordshire Foundation NHS Trust ShropDoc Shropshire County Council Telford & Wrekin Council CCG boundaries Powys Teaching Local Health Board • NHS Telford & Wrekin CCG • NHS Shropshire CCG Local Authority Boundaries • Telford & Wrekin Council: Unitary Authority • Shropshire County Council 31/01/2017 Shropshire and Telford & Wrekin Sustainability Transformation Plan 3 Contents Section Page Foreword 5 Executive Summary 6 Our Vision 9 Our Priorities and Plans 16 Our Enablers 70 Communications & Engagement 76 Governance & Leadership 86 Implementation 92 Support we Need 101 31/01/2017 Shropshire and Telford & Wrekin Sustainability Transformation Plan 4 Foreword This plan is ‘a work in progress’ and sets out our approach to transforming our local health and care system across Shropshire and Telford &Wrekin . -

Walk the Gorge KEY to MAPS Footpaths World Heritage Coalbrookdale Site Boundary Museums Museum

at the southern end of the Iron Bridge. Iron the of end southern the at Tollhouse February 2007 February obtained from the Tourist Information Centre in the in Centre Information Tourist the from obtained Bus timetables and further tourist information can be can information tourist further and timetables Bus town centre and Telford Central Railway Station. Railway Central Telford and centre town serves the Ironbridge Gorge area as well as Telford as well as area Gorge Ironbridge the serves please contact Traveline: contact please beginning of April to the end of October, the bus the October, of end the to April of beginning bus times and public transport public and times bus For more Information on other on Information more For every weekend and Bank Holiday Monday from the from Monday Holiday Bank and weekend every ! Operating ! bus Connect Gorge the on hop not Why tStbid BRIDGNORTH Church Stretton Church A458 A454 and the modern countryside areas. countryside modern the and WOLVERHAMPTON Much Wenlock Much A442 Broseley to search out both the industrial heritage of the area the of heritage industrial the both out search to A4169 A41 IRONBRIDGE Codsall Albrighton such as the South Telford Way, which will allow you allow will which Way, Telford South the as such (M6) A4169 M54 Leighton A49 to Birmingham to 3 A442 A5223 A458 Shifnal TELFORD area. Look out particularly for the marked routes, marked the for particularly out Look area. 4 5 A5 Atcham 6 M54 7 A5 SHREWSBURY oads in the in oads many other footpaths, bridleways and r and bridleways footpaths, other many Wellington A5 A41 M54 A458 A49 A518 There are of course of are There A5 A442 & N. -

Whitchurch to Shrewsbury

Leaflet Ref. No: NCN4D/July 2013 © Shropshire Council July 2013 July Council Shropshire © 2013 NCN4D/July No: Ref. Leaflet Designed by Salisbury NORTH SHROPSHIRE NORTH MA Creative Stonehenge •www.macreative.co.uk Transport for Department the by funded Part Marlborough 0845 113 0065 113 0845 Sustrans Sustrans www.sustrans.org.uk www.sustrans.org.uk www.wiltshire.gov.uk www.wiltshire.gov.uk by the charity Sustrans. charity the by % 01225 713404 01225 Swindon Wiltshire Council Wiltshire one of the award-winning projects coordinated coordinated projects award-winning the of one This route is part of the National Cycle Network, Network, Cycle National the of part is route This National Cycle Network Cycle National gov.uk/cycling Cirencester www.gloucestershire. Telford and Wrekin 01952 202826 202826 01952 Wrekin and Telford % 01452 425000 01452 County Council County For detailed local information, see cycle map of of map cycle see information, local detailed For Gloucestershire Gloucestershire 01743 253008 01743 Gloucester Shropshire Council Council Shropshire gov.uk/cms/cycling.aspx www.travelshropshire.co.uk www.travelshropshire.co.uk www.worcestershire. Worcester % 01906 765765 01906 ©Rosemary Winnall ©Rosemary County Council County Worcestershire Worcestershire Bewdley www.telford.gov.uk % 01952 380000 380000 01952 Council Bridgnorth Telford & Wrekin Wrekin & Telford co.uk Shrewsbury to Whitchurch to Shrewsbury www.travelshropshire. Ironbridge % 01743 253008 253008 01743 bike tracks in woods and forests. and woods in tracks bike Shropshire -

Advisory Visit Cound Brook, Shropshire June 2020

Advisory Visit Cound Brook, Shropshire June 2020 Author: Tim Jacklin ([email protected], tel. 07876 525457) 1.0 Introduction This report is the output of a site visit undertaken by Tim Jacklin of the Wild Trout Trust to the Cound Brook at Eaton Mascott Estate, Shropshire, on 10th June 2020. Comments in this report are based on observations during the site visit and discussions with the landowner. Normal convention is applied with respect to bank identification, i.e. left bank (LB) or right bank (RB) whilst looking downstream. Upstream and downstream references are often abbreviated to u/s and d/s, respectively, for convenience. The Ordnance Survey National Grid Reference system is used for identifying specific locations. 2.0 Catchment / Fishery Overview The section of the Cound Brook visited is located approximately 4km upstream of its confluence with the River Severn between Atcham and Cressage, south of Shrewsbury. A section of both the Cound Brook and its tributary the Row Brook were inspected upstream of their confluence. The geology of the area is sedimentary bedrock (Salop Formation – mudstone and sandstone, formed approximately 272 to 310 million years ago in the Permian and Carboniferous Periods1), with superficial deposits of river alluvium and glacial till. Soils in the vicinity are sandy and easily eroded. Combined with potato and maize cultivation, this tends to lead to excessive levels of fine sediment reaching the watercourses. In order to meet the requirements of the Water Framework Directive, the Environment Agency monitor the quality of watercourses using a number of measured parameters including plant, algae, invertebrate and fish populations, along with physical and chemical measures. -

01743 761220 Atcham, Shrewsbury, SY5 6QB Directions

www.myttonandmermaid.co.uk | 01743 761220 Atcham, Shrewsbury, SY5 6QB Directions Driving The Mytton and Mermaid Hotel is located between Telford and Shrewsbury on the B4380. 3 miles South east of Shrewsbury and 8 miles west of Telford. Approximately 25 minutes from Junction 10a off the M6. If travelling from the north, exit junction 11 off M6 and head for the M54. From M54 at Conference & Business first roundabout turn first left sign posted Shrewsbury, 2nd roundabout take first left again sign posted B4380 Atcham/Ironbridge. The Hotel is one mile on your right just over the Please find enclosed some information regarding the conference facilities at bridge and opposite Attingham Park a National Trust Stately home. The Mytton and Mermaid Hotel. Rail The nearest railway station is Shrewsbury If you do not see a package that suits your requirements please let us know and we will be more than happy to put together a personalized package for you. Airport The nearest airport is Birmingham Accommodation ~ We have 19 bedrooms all en-suite with private telephone and television and all with those little personal touches. Parking Complimentary WiFi ~ is available throughout the hotel. There is free car parking for up to 100 cars at both the front and back of the hotel. Buffet Menus cont... The Mytton Favourite Conference Rooms ‘Bangers & Mash’ Shropshire Fidget Sausage, Colcannon, Greens, Red Onion Gravy ~ The Mermaid Suite Sticky Toffee Pudding, Butterscotch Sauce, Vanilla Ice Cream Situated on the ground floor within the main hotel, this room is beautifully furnished with £16 a comfortable country house feel . -

702231 MODERN ARCHITECTURE a Nash and the Regency

702231 MODERN ARCHITECTURE A Nash and the Regency the Regency 1811-1830 insanity of George III rule of the Prince Regent 1811-20 rule of George IV (former Prince Regent) 1820-1830 the Regency style lack of theoretical structure cavalier attitude to classical authority abstraction of masses and volumes shallow decoration and elegant colours exterior stucco and light ironwork decoration eclectic use of Greek Revival and Gothick elements Georgian house in Harley Street, London: interior view. MUAS10,521 PROTO-REGENCY CHARACTERISTICS abstract shapes shallow plaster decoration light colouration Osterley Park, Middlesex (1577) remodelled by 20 Portman Square, London, the Adam Brothers, 1761-80: the Etruscan Room. by Robert Adam, 1775-7: the music room MUAS 2,550 MUAS 2,238 ‘Etruscan’ decoration by the Adam brothers Syon House, Middlesex, remodelled by Robert Portland Place, London, Adam from 1762: door of the drawing room by the Adam brothers from 1773: detail MUAS 10,579 MUAS 24,511 shallow pilasters the Empire Style in France Bed for Mme M, and Armchair with Swan vases, both from Percier & Fontaine, Receuil de Décorations (1801) Regency drawing room, from Thomas Hope, Household Furniture and Decoration (1807) Regency vernacular with pilastration Sandford Park Hotel, Bath Road, Cheltenham Miles Lewis Regency vernacular with blind arches and Greek fret pilasters Oriel Place, Bath Road, Cheltenham photos Miles Lewis Regency vernacular with balconies No 24, The Front, Brighton; two views in Bayswater Road, London MUAS 8,397, 8,220, 8,222 'Verandah' [balcony], from J B Papworth, Rural Residences, Consisting of a Series of Designs for Cottages, Decorated Cottages, Small Villas, and other Ornamental Buildings ..