Foreign Political Interference in the Governance of Listed Companies: a Market and Behavioral Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Integration of International Financial Regulatory Standards for the Chinese Economic Area: the Challenge for China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan Lawrence L.C

Northwestern Journal of International Law & Business Volume 20 Issue 1 Fall Fall 1999 Integration of International Financial Regulatory Standards for the Chinese Economic Area: The Challenge for China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan Lawrence L.C. Lee Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njilb Part of the International Law Commons, International Trade Commons, Law and Economics Commons, and the Securities Law Commons Recommended Citation Lawrence L.C. Lee, Integration of International Financial Regulatory Standards for the Chinese Economic Area: The hC allenge for China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan, 20 Nw. J. Int'l L. & Bus. 1 (1999-2000) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Northwestern Journal of International Law & Business by an authorized administrator of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. ARTICLES Integration of International Financial Regulatory Standards for the Chinese Economic Area: The Challenge for China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan Lawrence L. C. Lee* I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................... 2 II. ORIGINS OF THE CURRENT FINANCIAL AND BANKING SYSTEMS IN THE CHINESE ECONOMIC AREA ............................................................ 11 * Lawrence L. C. Lee is Assistant Professor at Ming Chung University School of Law (Taiwan) and Research Fellow at Columbia University School of Law. S.J.D. 1998, Univer- sity of Wisconsin-Madison Law School; LL.M. 1996, American University Washington College of Law; LL.M. 1993, Boston University School of Law; and LL.B. 1991, Soochow University School of Law (Taiwan). Portions of this article were presented at the 1999 Con- ference of American Association of Chinese Studies and the 1997 University of Wisconsin Law School Symposium in Legal Regulation of Cross-Straits Commercial Activities among Taiwan, Hong Kong, and China. -

Hang Seng Mainland China Companies High Dividend Yield Index

Hang Seng Mainland China Companies High Dividend Yield Index August 2021 The Hang Seng Mainland China Companies High Dividend Yield Index ("HSMCHYI") reflects the overall performance of Hong Kong listed Mainland companies with high dividend yield. FEATURES ■ The index comprises the 50 highest dividend yielding stocks among sizable Mainland companies that have demonstrated relatively lower price volatility and a persistent dividend payment record for the latest three fiscal years. ■ The index is net dividend yield- weighted with 10% cap on individual constituents. Data has been rebased at 100.00. All information for an index prior to its launch date is back-tested, back-tested performance INFORMATION reflects hypothetical historical performance. Launch Date 9 Sep 2019 INDEX PERFORMANCE Backdated To 31 Dec 2014 % Change Index Index Level Base Date 31 Dec 2014 1 - Mth 3 - Mth 6 - Mth 1 - Yr 3 - Yr 5 - Yr YTD Base Index 3,000 HSMCHYI 3,191.64 +7.42 -11.33 -7.46 +5.16 -7.37 +21.68 +2.40 Review Half-yearly HSMCHYI TRI 4,541.18 +7.76 -7.28 -2.51 +12.13 +10.20 +57.98 +7.87 Dissemination Every 2 sec INDEX FUNDAMENTALS Currency HKD Index Dividend Yield (%) PE Ratio (Times) Annual Volatility*(%) Total Return Index Available HSMCHYI 7.01 5.91 17.47 No. of Constituents 49 *Annual Volatility was calculated based on daily return for the past 12-month period. HSIDVP 602.10 VENDOR CODES All data as at 31 Aug 2021 Bloomberg HSMCHYI Refinitiv .HSMCHYI CONTACT US Email [email protected] Disclaimer All information contained herein is provided for reference only. -

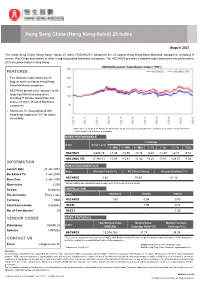

Hang Seng China (Hong Kong-Listed) 25 Index

Hang Seng China (Hong Kong-listed) 25 Index August 2021 The Hang Seng China (Hong Kong- listed) 25 Index ("HSCHK25") comprises the 25 largest Hong Kong-listed Mainland companies, including H shares, Red Chips and shares of other Hong Kong-listed Mainland companies. The HSCHK25 provides a tradable index that tracks the performance of China plays listed in Hong Kong. FEATURES ■ This thematic index tracks the 25 biggest and most liquid Hong Kong- listed Mainland companies ■ HSCHK25 provides an exposure to the large-cap Mainland companies, including H Shares, Red Chips and shares of other HK-listed Mainland companies ■ Stocks are freefloat-adjusted with weightings capped at 10% for higher investibility Data has been rebased at 100.00. All information for an index prior to its launch date is back-tested, back-tested performance reflects hypothetical historical performance. INDEX PERFORMANCE % Change Index Index Level 1 - Mth 3 - Mth 6 - Mth 1 - Yr 3 - Yr 5 - Yr YTD HSCHK25 8,630.19 +1.49 -13.50 -14.18 -0.67 -11.29 +6.71 -9.51 HSCHK25 TRI 17,191.11 +1.80 -11.81 -11.82 +2.47 -0.70 +28.57 -7.02 INFORMATION INDEX FUNDAMENTALS Launch Date 20 Jan 2003 Index Dividend Yield (%) PE Ratio (Times) Annual Volatility*(%) Backdated To 3 Jan 2000 HSCHK25 3.32 10.02 21.12 Base Date 3 Jan 2000 Base Index 2,000 *Annual Volatility was calculated based on daily return for the past 12-month period. Review Quarterly CORRELATION Dissemination Every 2 sec Index HSCHK25 HSCEI HSCCI Currency HKD HSCHK25 1.00 0.98 0.73 Total Return Index Available HSCEI - 1.00 0.73 No. -

FTSE Asia Pacific Ex Japan Australia and NZ Net 20 May 2014

FTSE PUBLICATIONS FTSE Asia Pacific ex Japan Australia 20 May 2014 and NZ Net Indicative Index Weight Data as at Closing on 31 March 2014 Index Index Index Constituent Country Constituent Country Constituent Country weight (%) weight (%) weight (%) AAC Technologies Holdings 0.12 HONG Beijing Capital International Airport (H) 0.03 CHINA China Development Financial Holdings 0.13 TAIWAN KONG Beijing Enterprises Holdings (Red Chip) 0.15 CHINA China Dongxiang Group (P Chip) 0.02 CHINA ABB India 0.02 INDIA Beijing Enterprises Water Group (Red Chip) 0.09 CHINA China Eastern Airlines (H) 0.02 CHINA Aboitiz Equity Ventures 0.09 PHILIPPINES Beijing Jingneng Clean Energy (H) 0.02 CHINA China Everbright (RED CHIP) 0.04 CHINA Aboitiz Power 0.04 PHILIPPINES Beijing North Star (H) 0.01 CHINA China Everbright International (Red Chip) 0.12 CHINA ACC 0.03 INDIA Belle International (P Chip) 0.17 CHINA China Foods (Red Chip) 0.01 CHINA Acer 0.05 TAIWAN Bengang Steel Plates (B) <0.005 CHINA China Galaxy Securities (H) 0.02 CHINA Adani Enterprises 0.05 INDIA Berjaya Sports Toto 0.03 MALAYSIA China Gas Holdings (P Chip) 0.08 CHINA Adani Ports and Special Economic Zone 0.05 INDIA Berli Jucker 0.02 THAILAND China Hongqiao Group (P Chip) 0.02 CHINA Adani Power 0.01 INDIA Bharat Electronics 0.01 INDIA China Huishan Dairy Holdings (P Chip) 0.03 CHINA Adaro Energy PT 0.04 INDONESIA Bharat Forge-A 0.02 INDIA China International Marine Containers (H) 0.04 CHINA Aditya Birla Nuvo 0.02 INDIA Bharat Heavy Elect .LS 0.06 INDIA China Life Insurance (H) 0.67 CHINA Advanced Info Serv 0.27 THAILAND Bharat Petroleum Corp 0.04 INDIA China Longyuan Power Group (H) 0.11 CHINA Advanced Semiconductor Engineering 0.22 TAIWAN Bharti Airtel 0.22 INDIA China Machinery Engineering (H) 0.01 CHINA Advantech 0.06 TAIWAN Bharti Infratel 0.02 INDIA China Mengniu Dairy 0.22 HONG Agile Property Holdings (P Chip) 0.03 CHINA Big C Supercenter 0.04 THAILAND KONG Agricultural Bank of China (H) 0.32 CHINA Biostime International Holdings (P Chip) 0.03 CHINA China Merchant Holdings (Red Chip) 0.13 CHINA AIA Group Ltd. -

Chinese Equities – the Guide March 2021

Chinese equities – the guide March 2021 For professional investors only. In Switzerland for Qualified Investors. In Australia for wholesale clients only. Not for use by retail investors or advisers. Introduction Investors who venture into the Chinese stock universe face an alphabet soup of seemingly random letters. There are A-shares, H-shares and S-chips to name just a few (see Chart 1). These letters represent various attempts to develop the equity market in a country where people traded the first shares as long ago as the 1860s. But something resembling a modern stock market, the Shenzhen Stock Exchange, didn’t start operations until 1 December 1990.1 Shenzhen beat Shanghai as the first exchange of the modern era by some three weeks.2 The Hong Kong Stock Exchange, a forerunner to the city’s current bourse, began operations in 1914 but developed under British colonial rule.3 Investors view Hong Kong as a separate and distinct market. Chart 1: Alphabet soup of Chinese equities Shares Listing Currency Country of Country Examples Index inclusion Comments Can Chinese incorporation where investors buy? company does most business A-share Shanghai + Renminbi China China Shanghai CSI 300 or MSCI Some have dual Y Shenzhen International China A Onshore. listing in H-share Airport Co. MSCI EM since market June 2018 B-share Shanghai + US dollar + China China N/A None Interest has Y Shenzhen Hong Kong collapsed since dollar H-shares H-share Hong Kong Hong Kong China China PetroChina, China MSCI China All Often dual listing Y dollar Construction -

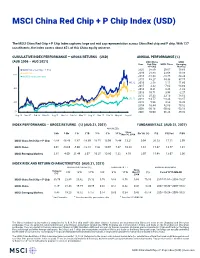

MSCI China Red Chip + P Chip Index (USD) (GROSS)

MSCI China Red Chip + P Chip Index (USD) The MSCI China Red Chip + P Chip Index captures large and mid cap representation across China Red chip and P chip. With 127 constituents, the index covers about 85% of this China equity universe. CUMULATIVE INDEX PERFORMANCE — GROSS RETURNS (USD) ANNUAL PERFORMANCE (%) (AUG 2006 – AUG 2021) MSCI China MSCI Year Red Chip MSCI China Emerging + P Chip Markets MSCI China Red Chip + P Chip 2020 38.09 29.67 18.69 MSCI China 2019 21.60 23.66 18.88 600 MSCI Emerging Markets 2018 -18.33 -18.75 -14.24 2017 68.27 54.33 37.75 485.42 2016 2.58 1.11 11.60 2015 3.32 -7.62 -14.60 400 2014 0.21 8.26 -1.82 366.92 2013 10.71 3.96 -2.27 2012 25.32 23.10 18.63 252.73 2011 -14.77 -18.24 -18.17 200 2010 5.99 4.83 19.20 2009 53.44 62.63 79.02 2008 -50.16 -50.83 -53.18 50 2007 80.00 66.24 39.82 Aug 06 Nov 07 Feb 09 May 10 Aug 11 Nov 12 Feb 14 May 15 Aug 16 Nov 17 Feb 19 May 20 Aug 21 INDEX PERFORMANCE — GROSS RETURNS (%) (AUG 31, 2021) FUNDAMENTALS (AUG 31, 2021) ANNUALIZED Since 1 Mo 3 Mo 1 Yr YTD 3 Yr 5 Yr 10 Yr Nov 30, 2004 Div Yld (%) P/E P/E Fwd P/BV MSCI China Red Chip + P Chip -0.86 -16.46 -1.07 -10.69 10.75 13.99 10.44 13.21 0.94 20.53 17.11 2.99 MSCI China 0.01 -13.69 -5.00 -12.18 7.42 10.97 7.47 10.83 1.61 15.47 13.57 1.91 MSCI Emerging Markets 2.65 -4.00 21.49 3.07 10.25 10.80 5.22 8.59 2.07 15.98 13.07 2.00 INDEX RISK AND RETURN CHARACTERISTICS (AUG 31, 2021) ANNUALIZED STD DEV (%) 2 SHARPE RATIO 2 , 3 MAXIMUM DRAWDOWN Turnover Since 1 3 Yr 5 Yr 10 Yr 3 Yr 5 Yr 10 Yr Nov 30, (%) Period YYYY-MM-DD (%) 2004 MSCI China Red Chip + P Chip 30.79 23.65 20.62 20.13 0.50 0.68 0.56 0.60 70.10 2007-11-01—2008-10-27 MSCI China 8.79 21.43 19.19 20.89 0.38 0.57 0.42 0.48 73.30 2007-10-30—2008-10-27 MSCI Emerging Markets 8.45 19.23 16.52 17.57 0.54 0.63 0.34 0.43 65.14 2007-10-29—2008-10-27 1 Last 12 months 2 Based on monthly gross returns data 3 Based on ICE LIBOR 1M The China mainland equity market is comprised of A, B, H, Red chip and P chip share classes. -

Market Facets a Realinsights Note June 2020

Realinsights #08-20 Market Facets A Realinsights Note June 2020 Forced Delisting of Chinese ADRs from US Exchanges – Is a market dislocation coming? Introduction Recent actions by China in Hong Kong and rising geopolitical tensions between China and the US have resulted in the US enacting the Holding Foreign Companies Accountable Act (“the Act”). One potential consequence of this Act is the forced delisting of Chinese American Depositary Receipts (ADRs) on US exchanges. This is relevant to index investors as these stocks represent a significant component of the China exposure in most major indices. In this paper, we investigate which companies are impacted, what the options are for these companies if they are forced to delist in the US, and what the market implications of forced delisting might be. Introduction China recently proposed a national security law1 in Hong Kong which sparked protests and condemnation from governments around the world. In response to recent Chinese government actions, the US administration has outlined a range of measures including the investigation of US listed Chinese companies with unusual practices. Under the new Act, if the US Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) is not able to audit a company for three consecutive years and determine that it is not under foreign control, the company will be delisted from all US Exchanges and any other trading method such as over-the-counter (OTC) trading. The law is particularly pertinent for Chinese companies as Chinese laws governing the protection of state secrets and national security have been invoked limiting foreign access to China-based audit work papers. -

FTSE Publications

2 FTSE Russell Publications 19 November 2019 FTSE Global Small Cap ex US Indicative Index Weight Data as at Closing on 30 September 2019 Index Index Index Constituent weight Country Constituent weight Country Constituent weight Country (%) (%) (%) 21Vianet Group (ADS) (N Shares) 0.03 CHINA Agrana Beteiligungs AG 0.01 AUSTRIA Allreal Hld N 0.12 SWITZERLAND 361 Degrees International (P Chip) 0.01 CHINA Agritrade Resources 0.01 HONG KONG Alm Brand 0.02 DENMARK 5I5j Holding Group (A) (SC SZ) <0.005 CHINA Agung Podomoro Land Tbk PT 0.01 INDONESIA Alpen 0.01 JAPAN 888 Holdings 0.02 UNITED Ahlstrom-Munksjo Oyl 0.03 FINLAND Alpha Networks 0.01 TAIWAN KINGDOM Ahnlab 0.01 KOREA Alpha Systems 0.01 JAPAN A.G.V. Products <0.005 TAIWAN Ai Holdings 0.03 JAPAN Alpiq Holding AG 0.01 SWITZERLAND AA 0.02 UNITED AIA Engineering 0.04 INDIA ALSO Holding AG 0.02 SWITZERLAND KINGDOM Aichi Bank Ltd 0.01 JAPAN Alstria Office 0.12 GERMANY AAK 0.15 SWEDEN Aichi Corp 0.01 JAPAN AltaGas. 0.18 CANADA Aareal Bank AG 0.08 GERMANY Aichi Steel 0.01 JAPAN Altarea 0.04 FRANCE Aarti Industries 0.02 INDIA Aida Engineering 0.02 JAPAN Altek Corp 0.01 TAIWAN Aavas Financiers 0.02 INDIA Aiful 0.03 JAPAN Alten 0.14 FRANCE Abacus Property Group 0.04 AUSTRALIA AIMS APAC REIT 0.02 SINGAPORE Altice Europe NV A 0.13 NETHERLANDS Abdulmohsen Al Hokair Group for Tourism <0.005 SAUDI ARABIA Ainsworth Game Technology Ltd <0.005 AUSTRALIA Altice Europe NV B 0.01 NETHERLANDS and Development Co C Aiphone 0.01 JAPAN Altran Techn. -

China: Too Big to Ignore

China: Too big to ignore Navigating Chinese equities This document is for the exclusive us of investors acting on their own account and categorised either as “eligible counterparties” or “professional clients” within the meaning of markets in financial instruments directive 2014/65/EU. Access Markets February 2020 Access Markets | China: too big to ignore 3 China: too big to ignore Despite being the second biggest market in the world and one of the fastest growing economies, foreign investment in China remains low. As a result of ongoing market liberalisation, inflows from foreign portfolio investors are likely to increase significantly over the next few years, particularly in the A share market. We believe it may be time to consider China as a standalone portfolio allocation. ... is not reflected in China’s huge economy... equity markets #2 US #1 2.3% 330m tn % $21.4tn $21.4tn $34.3 55.6 VS. GDP GDP GDP growth1 Population1 Stock market2 % of MSCI (nominal)1 (at PPP*)1 (free float ACWI3 mkt cap*) #2 #1 China 6.1% 1.4bn ~$3.7tn 4.2% $13.6tn $27.3tn 1Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook, October 2019. *PPP = Purchasing Power Parity 2Source: MSCI, as at 31/12/2019. Data does not include ETFs and ADRs as they do not directly represent companies. Data includes only actively traded, primary securities on the country’s exchange. For China, data corresponds to combined market cap of HK, Shanghai and Shenzhen listings, based on total market capitalisation. (*) MSCI IMI indices. 3Source: Lyxor International Asset Management. Data as of 31/01/2020. -

Listing PRC Companies in Hong Kong Using VIE Structures

Listing PRC Companies in Hong Kong Using VIE Structures October 2014 www.charltonslaw.com 0 Index Page Executive summary 2 Contents 。 Hong Kong Stock Exchange (HKEx)’s background information 4 。 Introduction to listing of PRC companies on HKEx 15 。 VIE structure 21 。 Key requirement of Main Board listing on HKEx 30 。 Requirements for a listing – Hong Kong vs U.S. 39 About Charltons 46 Disclaimer 47 1 Executive summary Hong Kong market is the 6th largest stock market in the world Hong Kong ranked 3rd worldwide in terms of IPO funds raised (only after NYSE and Nasdaq) in 2013 VIE structures can be listed on The Hong Kong Stock Exchange (HKEx) subject to complying with requirements of listing decision ○ certain businesses maybe subject to PRC’s foreign investment restriction if they belong to certain industry sectors (Restricted Industries) ○ Restricted industries include compulsory education, news agencies and internet-related services Key Hong Kong listing requirements: ○ three financial criteria: (1) the profit test ; (2) the market capitalisation/revenue test; or (3) the market capitalisation/revenue/ cashflow test ○ A 3-year track record period requirement is usually applied to a listing applicant * HKEx may also accept a shorter trading record period and/or may vary or waive the financial standards requirements on certain circumstances ○ Maintain at all times a minimum public float of 25% of the Company’s total issued share capital 2 Executive summary Key U.S. listing requirements ○ minimum quantitative requirements, which -

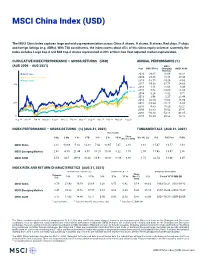

MSCI China Index (USD)

MSCI China Index (USD) The MSCI China Index captures large and mid cap representation across China A shares, H shares, B shares, Red chips, P chips and foreign listings (e.g. ADRs). With 730 constituents, the index covers about 85% of this China equity universe. Currently, the index includes Large Cap A and Mid Cap A shares represented at 20% of their free float adjusted market capitalization. CUMULATIVE INDEX PERFORMANCE — GROSS RETURNS (USD) ANNUAL PERFORMANCE (%) (AUG 2006 – AUG 2021) MSCI Year MSCI China Emerging MSCI ACWI Markets MSCI China 2020 29.67 18.69 16.82 MSCI Emerging Markets 2019 23.66 18.88 27.30 MSCI ACWI 2018 -18.75 -14.24 -8.93 400 2017 54.33 37.75 24.62 366.92 2016 1.11 11.60 8.48 324.55 2015 -7.62 -14.60 -1.84 2014 8.26 -1.82 4.71 2013 3.96 -2.27 23.44 252.73 2012 23.10 18.63 16.80 200 2011 -18.24 -18.17 -6.86 2010 4.83 19.20 13.21 2009 62.63 79.02 35.41 2008 -50.83 -53.18 -41.85 50 2007 66.24 39.82 12.18 Aug 06 Nov 07 Feb 09 May 10 Aug 11 Nov 12 Feb 14 May 15 Aug 16 Nov 17 Feb 19 May 20 Aug 21 INDEX PERFORMANCE — GROSS RETURNS (%) (AUG 31, 2021) FUNDAMENTALS (AUG 31, 2021) ANNUALIZED Since 1 Mo 3 Mo 1 Yr YTD 3 Yr 5 Yr 10 Yr Dec 31, 1992 Div Yld (%) P/E P/E Fwd P/BV MSCI China 0.01 -13.69 -5.00 -12.18 7.42 10.97 7.47 2.18 1.61 15.47 13.57 1.91 MSCI Emerging Markets 2.65 -4.00 21.49 3.07 10.25 10.80 5.22 7.75 2.07 15.98 13.07 2.00 MSCI ACWI 2.53 4.67 29.18 16.24 14.91 14.88 11.86 8.88 1.71 22.54 18.46 3.07 INDEX RISK AND RETURN CHARACTERISTICS (AUG 31, 2021) ANNUALIZED STD DEV (%) 2 SHARPE RATIO 2 , 3 MAXIMUM DRAWDOWN Turnover Since 1 3 Yr 5 Yr 10 Yr 3 Yr 5 Yr 10 Yr Dec 31, (%) Period YYYY-MM-DD (%) 1992 MSCI China 8.79 21.43 19.19 20.89 0.38 0.57 0.42 0.14 88.63 1993-12-31—2001-09-12 MSCI Emerging Markets 8.45 19.23 16.52 17.57 0.54 0.63 0.34 0.33 65.14 2007-10-29—2008-10-27 MSCI ACWI 3.17 17.93 14.46 13.77 0.80 0.95 0.83 0.47 58.06 2007-10-31—2009-03-09 1 Last 12 months 2 Based on monthly gross returns data 3 Based on ICE LIBOR 1M The China mainland equity market is comprised of A, B, H, Red chip and P chip share classes. -

Tapping Into a Broader Range of Investment

For professional / institutional investors only TAPPING INTO A BROADER RANGE OF INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITIES AS CHINA MARKET OPENS UP Tapping into a broader range of investment opportunities as China market opens up | November 2018 RISK FACTORS This document is a financial promotion for The First State China Strategy. This information is for professional and institutional investors only in the EEA and elsewhere where lawful. Investing involves certain risks including: • The value of investments and any income from them may go down as well as up and are not guaranteed. Investors may get back significantly less than the original amount invested. • Currency risk: Changes in exchange rates will affect the value of assets which are denominated in other currencies. • Single country / specific region risk: Investing in a single country or specific region may be riskier than investing in a number of different countries or regions. Investing in a larger number of countries or regions helps spread risk. • China market risk: Investing in the Chinese market involves risks such as legal, regulatory and economic risks. The securities markets in China may be subject to greater uncertainty than investments in more developed countries. • Concentration risk: Investments are made in a relatively small number of companies or countries which may be riskier than if investments are made in a larger number of companies or countries. • Emerging market risk: Emerging markets may not provide the same level of investor protection as a developed market; they may involve a higher risk than investing in developed markets. Reference to specific securities or companies (if any) are included to explain the investment strategy and should not be construed as investment advice, or a recommendation to invest in any of those companies.