Botany-Illustrated-J.-Glimn-Lacy-P.-Kaufman-Springer-2006.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Field Release of the Leaf-Feeding Moth, Hypena Opulenta (Christoph)

United States Department of Field release of the leaf-feeding Agriculture moth, Hypena opulenta Marketing and Regulatory (Christoph) (Lepidoptera: Programs Noctuidae), for classical Animal and Plant Health Inspection biological control of swallow- Service worts, Vincetoxicum nigrum (L.) Moench and V. rossicum (Kleopow) Barbarich (Gentianales: Apocynaceae), in the contiguous United States. Final Environmental Assessment, August 2017 Field release of the leaf-feeding moth, Hypena opulenta (Christoph) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), for classical biological control of swallow-worts, Vincetoxicum nigrum (L.) Moench and V. rossicum (Kleopow) Barbarich (Gentianales: Apocynaceae), in the contiguous United States. Final Environmental Assessment, August 2017 Agency Contact: Colin D. Stewart, Assistant Director Pests, Pathogens, and Biocontrol Permits Plant Protection and Quarantine Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service U.S. Department of Agriculture 4700 River Rd., Unit 133 Riverdale, MD 20737 Non-Discrimination Policy The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination against its customers, employees, and applicants for employment on the bases of race, color, national origin, age, disability, sex, gender identity, religion, reprisal, and where applicable, political beliefs, marital status, familial or parental status, sexual orientation, or all or part of an individual's income is derived from any public assistance program, or protected genetic information in employment or in any program or activity conducted or funded by the Department. (Not all prohibited bases will apply to all programs and/or employment activities.) To File an Employment Complaint If you wish to file an employment complaint, you must contact your agency's EEO Counselor (PDF) within 45 days of the date of the alleged discriminatory act, event, or in the case of a personnel action. -

"National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary."

Intro 1996 National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands The Fish and Wildlife Service has prepared a National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary (1996 National List). The 1996 National List is a draft revision of the National List of Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1988 National Summary (Reed 1988) (1988 National List). The 1996 National List is provided to encourage additional public review and comments on the draft regional wetland indicator assignments. The 1996 National List reflects a significant amount of new information that has become available since 1988 on the wetland affinity of vascular plants. This new information has resulted from the extensive use of the 1988 National List in the field by individuals involved in wetland and other resource inventories, wetland identification and delineation, and wetland research. Interim Regional Interagency Review Panel (Regional Panel) changes in indicator status as well as additions and deletions to the 1988 National List were documented in Regional supplements. The National List was originally developed as an appendix to the Classification of Wetlands and Deepwater Habitats of the United States (Cowardin et al.1979) to aid in the consistent application of this classification system for wetlands in the field.. The 1996 National List also was developed to aid in determining the presence of hydrophytic vegetation in the Clean Water Act Section 404 wetland regulatory program and in the implementation of the swampbuster provisions of the Food Security Act. While not required by law or regulation, the Fish and Wildlife Service is making the 1996 National List available for review and comment. -

Asphodelus Fistulosus (Asphodelaceae, Asphodeloideae), a New Naturalised Alien Species from the West Coast of South Africa ⁎ J.S

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com South African Journal of Botany 79 (2012) 48–50 www.elsevier.com/locate/sajb Research note Asphodelus fistulosus (Asphodelaceae, Asphodeloideae), a new naturalised alien species from the West Coast of South Africa ⁎ J.S. Boatwright Compton Herbarium, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Private Bag X7, Claremont 7735, South Africa Department of Botany and Plant Biotechnology, University of Johannesburg, P.O. Box 524, Auckland Park 2006, Johannesburg, South Africa Received 4 November 2011; received in revised form 18 November 2011; accepted 21 November 2011 Abstract Asphodelus fistulosus or onionweed is recorded in South Africa for the first time and is the first record of an invasive member of the Asphodelaceae in the country. Only two populations of this plant have been observed, both along disturbed roadsides on the West Coast of South Africa. The extent and invasive potential of this infestation in the country is still limited but the species is known to be an aggressive invader in other parts of the world. © 2011 SAAB. Published by Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. Keywords: Asphodelaceae; Asphodelus; Invasive species 1. Introduction flowers (Patterson, 1996). This paper reports on the presence of this species in South Africa. A population of A. fistulosus was The genus Asphodelus L. comprises 16 species distributed in first observed in the early 1990's by Drs John Manning and Eurasia and the Mediterranean (Días Lifante and Valdés, 1996). Peter Goldblatt during field work for their Wild Flower Guide It is superficially similar to the largely southern African to the West Coast (Manning and Goldblatt, 1996). -

Annual Plant Reviews Volume 45: the Evolution of Plant Form

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235418621 Annual Plant Reviews Volume 45: The Evolution of Plant Form Chapter · January 2013 DOI: 10.1002/9781118305881.ch4 CITATIONS READS 12 590 1 author: Harald Schneider Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden 374 PUBLICATIONS 14,108 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Nuclear DNA C‐values in ferns and lycophytes of Argentina View project Pteridophyte Phylogeny Group View project All content following this page was uploaded by Harald Schneider on 19 June 2017. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. BLBK441-c04 BLBK441-Ambrose Trim: 234mm 156mm September 15, 2012 11:24 × Annual Plant Reviews (2013) 45, 115–140 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com doi: 10.1002/9781118305881.ch4 Chapter 4 EVOLUTIONARY MORPHOLOGY OF FERNS (MONILOPHYTES) Harald Schneider Department of Botany, Natural History Museum, London, UK Abstract: Throughout its long history, concepts of plant morphology have been mainly developed by studying seed plants, in particular angiosperms. This chap- ter provides an overview to the morphology of ferns by exploring the evolutionary background of the early diversification of ferns, by discussing the main structures and organs of ferns, and finally by exploring our current knowledge of fern ge- nomics and evolutionary developmental biology. Horsetails (Equisetopsida) and whisk ferns (Psilotales) are treated as part of the fern lineage. Throughout the chap- ter, I employ a process-oriented approach, which combines the process orientation of the Arberian Fuzzy Morphology with the process orientation of Darwinian evolution as reflected in current phylogenetics. -

Fair Use of This PDF File of Herbaceous

Fair Use of this PDF file of Herbaceous Perennials Production: A Guide from Propagation to Marketing, NRAES-93 By Leonard P. Perry Published by NRAES, July 1998 This PDF file is for viewing only. If a paper copy is needed, we encourage you to purchase a copy as described below. Be aware that practices, recommendations, and economic data may have changed since this book was published. Text can be copied. The book, authors, and NRAES should be acknowledged. Here is a sample acknowledgement: ----From Herbaceous Perennials Production: A Guide from Propagation to Marketing, NRAES- 93, by Leonard P. Perry, and published by NRAES (1998).---- No use of the PDF should diminish the marketability of the printed version. This PDF should not be used to make copies of the book for sale or distribution. If you have questions about fair use of this PDF, contact NRAES. Purchasing the Book You can purchase printed copies on NRAES’ secure web site, www.nraes.org, or by calling (607) 255-7654. Quantity discounts are available. NRAES PO Box 4557 Ithaca, NY 14852-4557 Phone: (607) 255-7654 Fax: (607) 254-8770 Email: [email protected] Web: www.nraes.org More information on NRAES is included at the end of this PDF. Acknowledgments This publication is an update and expansion of the 1987 Cornell Guidelines on Perennial Production. Informa- tion in chapter 3 was adapted from a presentation given in March 1996 by John Bartok, professor emeritus of agricultural engineering at the University of Connecticut, at the Connecticut Perennials Shortcourse, and from articles in the Connecticut Greenhouse Newsletter, a publication put out by the Department of Plant Science at the University of Connecticut. -

Playing with Extremes Origins and Evolution of Exaggerated Female

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 115 (2017) 95–105 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Playing with extremes: Origins and evolution of exaggerated female forelegs MARK in South African Rediviva bees ⁎ Belinda Kahnta,b, , Graham A. Montgomeryc, Elizabeth Murrayc, Michael Kuhlmannd,e, Anton Pauwf, Denis Michezg, Robert J. Paxtona,b, Bryan N. Danforthc a Institute of Biology/General Zoology, Martin-Luther-University Halle-Wittenberg, Hoher Weg 8, 06120 Halle (Saale), Germany b German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) Halle-Jena-Leipzig, Deutscher Platz 5e, 04103 Leipzig, Germany c Department of Entomology, Cornell University, 3124 Comstock Hall, Ithaca, NY 14853-2601, USA d Zoological Museum, Kiel University, Hegewischstr. 3, 24105 Kiel, Germany e Dept. of Life Sciences, Natural History Museum, Cromwell Rd., London SW7 5BD, UK f Department of Botany and Zoology, Stellenbosch University, Matieland 7602, South Africa g Laboratoire de Zoologie, Research institute of Biosciences, University of Mons, Place du Parc 23, 7000 Mons, Belgium ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Despite close ecological interactions between plants and their pollinators, only some highly specialised polli- Molecular phylogenetics nators adapt to a specific host plant trait by evolving a bizarre morphology. Here we investigated the evolution Plant-pollinator interaction of extremely elongated forelegs in females of the South African bee genus Rediviva (Hymenoptera: Melittidae), in Ecological adaptation which long forelegs are hypothesised to be an adaptation for collecting oils from the extended spurs of their Greater cape floristic region Diascia host flowers. We first reconstructed the phylogeny of the genus Rediviva using seven genes and inferred Trait evolution an origin of Rediviva at around 29 MYA (95% HPD = 19.2–40.5), concurrent with the origin and radiation of the Melittidae Succulent Karoo flora. -

Outline of Angiosperm Phylogeny

Outline of angiosperm phylogeny: orders, families, and representative genera with emphasis on Oregon native plants Priscilla Spears December 2013 The following listing gives an introduction to the phylogenetic classification of the flowering plants that has emerged in recent decades, and which is based on nucleic acid sequences as well as morphological and developmental data. This listing emphasizes temperate families of the Northern Hemisphere and is meant as an overview with examples of Oregon native plants. It includes many exotic genera that are grown in Oregon as ornamentals plus other plants of interest worldwide. The genera that are Oregon natives are printed in a blue font. Genera that are exotics are shown in black, however genera in blue may also contain non-native species. Names separated by a slash are alternatives or else the nomenclature is in flux. When several genera have the same common name, the names are separated by commas. The order of the family names is from the linear listing of families in the APG III report. For further information, see the references on the last page. Basal Angiosperms (ANITA grade) Amborellales Amborellaceae, sole family, the earliest branch of flowering plants, a shrub native to New Caledonia – Amborella Nymphaeales Hydatellaceae – aquatics from Australasia, previously classified as a grass Cabombaceae (water shield – Brasenia, fanwort – Cabomba) Nymphaeaceae (water lilies – Nymphaea; pond lilies – Nuphar) Austrobaileyales Schisandraceae (wild sarsaparilla, star vine – Schisandra; Japanese -

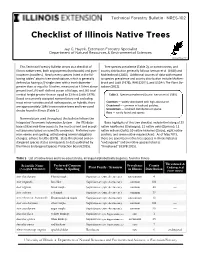

Checklist of Illinois Native Trees

Technical Forestry Bulletin · NRES-102 Checklist of Illinois Native Trees Jay C. Hayek, Extension Forestry Specialist Department of Natural Resources & Environmental Sciences Updated May 2019 This Technical Forestry Bulletin serves as a checklist of Tree species prevalence (Table 2), or commonness, and Illinois native trees, both angiosperms (hardwoods) and gym- county distribution generally follows Iverson et al. (1989) and nosperms (conifers). Nearly every species listed in the fol- Mohlenbrock (2002). Additional sources of data with respect lowing tables† attains tree-sized stature, which is generally to species prevalence and county distribution include Mohlen- defined as having a(i) single stem with a trunk diameter brock and Ladd (1978), INHS (2011), and USDA’s The Plant Da- greater than or equal to 3 inches, measured at 4.5 feet above tabase (2012). ground level, (ii) well-defined crown of foliage, and(iii) total vertical height greater than or equal to 13 feet (Little 1979). Table 2. Species prevalence (Source: Iverson et al. 1989). Based on currently accepted nomenclature and excluding most minor varieties and all nothospecies, or hybrids, there Common — widely distributed with high abundance. are approximately 184± known native trees and tree-sized Occasional — common in localized patches. shrubs found in Illinois (Table 1). Uncommon — localized distribution or sparse. Rare — rarely found and sparse. Nomenclature used throughout this bulletin follows the Integrated Taxonomic Information System —the ITIS data- Basic highlights of this tree checklist include the listing of 29 base utilizes real-time access to the most current and accept- native hawthorns (Crataegus), 21 native oaks (Quercus), 11 ed taxonomy based on scientific consensus. -

Taxa Named in Honor of Ihsan A. Al-Shehbaz

TAXA NAMED IN HONOR OF IHSAN A. AL-SHEHBAZ 1. Tribe Shehbazieae D. A. German, Turczaninowia 17(4): 22. 2014. 2. Shehbazia D. A. German, Turczaninowia 17(4): 20. 2014. 3. Shehbazia tibetica (Maxim.) D. A. German, Turczaninowia 17(4): 20. 2014. 4. Astragalus shehbazii Zarre & Podlech, Feddes Repert. 116: 70. 2005. 5. Bornmuellerantha alshehbaziana Dönmez & Mutlu, Novon 20: 265. 2010. 6. Centaurea shahbazii Ranjbar & Negaresh, Edinb. J. Bot. 71: 1. 2014. 7. Draba alshehbazii Klimeš & D. A. German, Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 158: 750. 2008. 8. Ferula shehbaziana S. A. Ahmad, Harvard Pap. Bot. 18: 99. 2013. 9. Matthiola shehbazii Ranjbar & Karami, Nordic J. Bot. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-1051.2013.00326.x, 10. Plocama alshehbazii F. O. Khass., D. Khamr., U. Khuzh. & Achilova, Stapfia 101: 25. 2014. 11. Alshehbazia Salariato & Zuloaga, Kew Bulletin …….. 2015 12. Alshehbzia hauthalii (Gilg & Muschl.) Salariato & Zuloaga 13. Ihsanalshehbazia Tahir Ali & Thines, Taxon 65: 93. 2016. 14. Ihsanalshehbazia granatensis (Boiss. & Reuter) Tahir Ali & Thines, Taxon 65. 93. 2016. 15. Aubrieta alshehbazii Dönmez, Uǧurlu & M.A.Koch, Phytotaxa 299. 104. 2017. 16. Silene shehbazii S.A.Ahmad, Novon 25: 131. 2017. PUBLICATIONS OF IHSAN A. AL-SHEHBAZ 1973 1. Al-Shehbaz, I. A. 1973. The biosystematics of the genus Thelypodium (Cruciferae). Contrib. Gray Herb. 204: 3-148. 1977 2. Al-Shehbaz, I. A. 1977. Protogyny, Cruciferae. Syst. Bot. 2: 327-333. 3. A. R. Al-Mayah & I. A. Al-Shehbaz. 1977. Chromosome numbers for some Leguminosae from Iraq. Bot. Notiser 130: 437-440. 1978 4. Al-Shehbaz, I. A. 1978. Chromosome number reports, certain Cruciferae from Iraq. -

Hillier Nurseries Launches Choisya 'Aztec Gold', the Latest Masterpiece

RHS Chelsea 2012: Hillier New Plant Introduction Hillier Nurseries launches Choisya ‘Aztec Gold’, the latest masterpiece from Alan Postill, 50 years a Hillier plantsman New to Hillier Nurseries, the UK & the world in 2012 Celebrating 50 years this summer as a Hillier plantsman, man and boy, Alan Postill has done it again. The highly respected propagator of Daphne bholua ‘Jaqueline Postill’ and Digitalis ‘Serendipity’ has bred a sensational new golden form of the Mexican orange blossom, which is up for Chelsea New Plant of the Year. Choisya ‘Aztec Gold’ is an attractive, bushy, evergreen shrub with striking, golden, aromatic foliage - rich gold at the ends of the shoots, green-gold in the heart of the plant. Its slender leaflets are very waxy and weather resistant, and do not suffer the winter damage of other golden foliage varieties. In spring and early summer, and then again in autumn, delicious almond-scented white flowers appear, attracting bees and butterflies. In Choisya ‘Aztec Gold’, Alan Postill has realised his objective of creating a remarkably strong-growing, golden foliage form of the Choisya ‘Aztec Pearl’, which Hillier introduced 30 years ago in1982, and has since become one of the nation’s best-selling and best-loved garden shrubs. Knowing its pedigree and performance in real gardens, Alan selected Choisya ‘Aztec Pearl’ as one of the parent plants for the new variety. Choisya ‘Aztec Gold’ performs well in any reasonably fertile well-drained soil in full sun or partial shade, although the colour will be less golden in shade, of course. It is ideally suited to a mixed border or a large container, and planted with other gold foliage or gold variegated shrubs, or contrasted with blue flowers or plum-purple foliage. -

Green Leaf Perennial Catalog.Pdf

Green Leaf Plants® A Division of Aris Horticulture, Inc. Perennials & Herbs 2013/2014 Visit us @ Green Leaf Plants® GLplants.com Green Leaf Plants® Perennial Management Teams Green Leaf Plants® Lancaster, Pennsylvania Green Leaf Plants® Bogotá, Colombia (Pictured Left to Right) Rich Hollenbach, Grower Manager and Production Planning/Inventory Control (Pictured Left to Right) Silvia Guzman, Farm Manager I Isabel Naranjo, Lab Manager I Juan Camilo Manager I Andrew Bishop, Managing Director I Sara Bushong, Customer Service Manager and Herrera, Manager of Latin American Operations & Sales Logistics Manager Cindy Myers, Human Resources and Administration Manager I Nancy Parr, Product Manager Customer Service Glenda Bradley Emma Bishop Jenny Cady Wendy Fromm Janis Miller Diane Lemke Yvonne McCauley [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Ext. 229 Ext. 227 Ext. 245 Ext. 223 Ext. 221 Ext. 231 Ext. 237 Management, Tech Support and New Product Development Brad Smith Sarah Rasch Sara Bushong, Nancy Parr, Product Mgr. Julie Knauer, Prod. Mgr. Asst Susan Shelly, Tech Support Melanie Neff, New Product Development [email protected] [email protected] C.S. Mgr. & Logistics Mgr. [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Ext. 228 800.232.9557 Ext. 5007 [email protected] Ext. 270 Ext. 288 Ext. 238 Ext. 273 Ext. 250 Varieties Pictured: Arctotis Peachy Mango™ Aster Blue Autumn® Colocasia Royal Hawaiian® DID YOU KNOW? ‘Blue Hawaii’ Customer service means more than answering the phone and Delphinium ‘Diamonds Blue’ Echinacea ‘Supreme Elegance’ taking orders. -

Asphodelus Microcarpus Against Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Isolates

Available online on www.ijppr.com International Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemical Research 2016; 8(12); 1964-1968 ISSN: 0975-4873 Research Article Antibacterial Activity of Asphodelin lutea and Asphodelus microcarpus Against Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Isolates Rawaa Al-Kayali1*, Adawia Kitaz2, Mohammad Haroun3 1Biochemistry and Microbiology Dep., Faculty of Pharmacy, Aleppo University, Syria 2Pharmacognosy Dep., Faculty of Pharmacy, Aleppo University, Syria 3Faculty of Pharmacy, Al Andalus University for Medical Sciences, Syria Available Online: 15th December, 2016 ABSTRACT Objective: the present study aimed at evaluation of antibacterial activity of wild local Asphodelus microcarpus and Asphodeline lutea against methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) isolates.. Methods: Antimicrobial activity of the crude extracts was evaluated against MRSA clinical isolates using agar wells diffusion. Determination of minimum inhibitory concentration( MIC)of methanolic extract of two studied plants was also performed using tetrazolium microplate assay. Results: Our results showed that different extracts (20 mg/ml) of aerial parts and bulbs of the studied plants were exhibited good growth inhibitory effect against methicilline resistant S. aureus isolates and reference strain. The inhibition zone diameters of A. microcarpus and A. lutea ranged from 9.3 to 18.6 mm and from 6.6 to 15.3mm respectively. All extracts have better antibacterial effect than tested antibiotics against MRSA isolate. The MIC of the methanolic extracts of A. lutea and A. microcarpus for MRSA fell in the range of 0.625 to 2.5 mg/ml and of 1.25-5 mg/ml, respectively. conclusion:The extracts of A. lutea and A. microcarpus could be a possible source to obtain new antibacterial to treat infections caused by MRSA isolates.