2016 Maketas.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paul Gauguin

Sarah Kapp Art History and Visual Studies Major (honours) Business Minor De-Mythicizing the Artist: Presented March 6, 2019 This research was supported by the Jamie Cassels Undergraduate Research Award University of Victoria Supervised by Dr. Catherine Harding How Gauguin Responded to the Art Market Assistance from Dr. Melissa Berry Political Conditions Introduction Imperialism and Primitivism in the Late-Nineteenth Century Like celebrities, famous artists face rumours and myths Gauguin’s stylistic innovations were just one component of his self-promotional endeavor that overwhelm their public reception. Vincent van Gogh that appeared in the Volpini Suite. It was his engagement with ‘primitive’ subject- has become inextricably linked to the tale of the tortured matter—which included depictions of local peasant and folk culture—that served as a soul who sliced off his ear; Pablo Picasso to the tale fashionable and marketable technique (Perry 6). In the 1889 suite, Gauguin depicted of the womanizing innovative artist; and Salvador Dalí people in their daily surroundings, including: Breton peasant women chatting, Martinican as the eccentric artist who did too many drugs. This women carrying baskets of fruit, and women from Arles out walking (Juszczak 119). research dismantles the myth of Paul Gauguin (1848- After his creation of the Volpini Suite, Gauguin’s use of ‘primitive’ subjects intensified, 1903), who, in the late-twentieth century, became ultimately becoming a defining feature of his artistic practice. Gauguin’s work in the the target of feminist and post-colonialist theorists, Volpini Show correlated to contemporary ideas about the ‘primitive’. The Exposition who criticized him for sexualized depictions of young Universelle juxtaposed the newly built Eiffel Tower and the Gallery of Machines with women, as well as ‘plagiarizing’ and ‘pillaging’ the art ethnographic exhibits from around the world (Chu 439). -

Paul Gauguin L'aventurier Des Arts

PAUL GAUGUIN L’Aventurier des arts Texte Géraldine PUIREUX lu par Julien ALLOUF translated by Marguerite STORM read by Stephanie MATARD © Éditions Thélème, Paris, 2020 CONTENTS SOMMAIRE 6 6 1848-1903 L’apostrophe du maître de la pose et de la prose 1848-1903 The master of pose and prose salute 1848-1864 Une mythologie familiale fondatrice d’un charisme personnel 1848-1864 Family mythology generating personal charisma 1865-1871 Un jeune marin du bout du monde 1865-1871 A far-flung young sailor 1872-1874 L’agent de change donnant le change en société devient très artiste 1872-1874 The stockbroker becomes a code-broker artist 8 8 1874-1886 Tirer son épingle du jeu avec les Impressionnistes 1874-1886 Playing ball with the Impressionists 1886-1887 Le chef de file de l’École de Pont-Aven 1886-1887 The leader of the Pont-Aven School 1887-1888 L’aventure au Panama et la révélation de la Martinique 1887-1888 Adventure in Panama and a revelation in Martinique 1888-1889 L’atelier du Midi à Arles chez van Gogh : un séjour à pinceaux tirés 1888-1889 Van Gogh’s atelier du Midi in Arles: a stay hammered with paintbrushes 1889-1890 Vivre et s’exposer, avec ou sans étiquette, avec ou sans les autres 1889-1890 Living and exhibiting, with or without label, with or without others 46 46 1891-1892 Un dandy tiré à quatre épingles, itinérant et sauvage 1891-1892 A wild, dressed-to-the-teeth travelling dandy 1893-1894 En peignant la Javanaise : Coup de Jarnac à Concarneau 1893-1894 Painting Javanaise Woman: Jarnac blow in Concarneau 1895 Le retour à Pont-Aven -

Mnittv of Fmt ^Rt (M

PAULGAUGUIN AS IMPRESSIONIST PAINTER - A CRITICAL STUDY DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIRIMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF Mnittv of fmt ^rt (M. F. A.) BT MS. SAB1YA K4iATQQTI Under the supervision of 0^v\o-vO^V\CM ' r^^'JfJCA'-I ^ M.JtfzVl Dr. (Mrs.) SIRTAJ RIZVl Co-Supervisor PARTMENT OF FINE ART IGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 1997 DS2890 ^^ -2-S^ 0 % ^eAtcMed to ^ff ^urents CHAIRMAN ALiGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF FINE ARTS ALIGARH—202 002 (U.P.). INDIA Dated. TO WHOM IT BIAY CONCERN This is to certify that Miss Sabiya Khatoon of Master of Fine Arts (M.F.A.) has completed her dissertation entitled "PAOL GAUGUIN AS IMPRESSIONIST PAINTER - A CRITICAL STUDY", under the supervision of Prof. Ashfaq M. Rizvi and Co-Supervision Dr. (Mrs.) Sirtaj Rizvi, Reader, Department of Fine Arts. To the best of my knowledge and belief, the work is based on the investigations made, data collected and analysed by her and it has not been submitted in any other University or Institution for any Degree. 15th MAY, 1997 ( B4RS. SEEMA JAVED ) ALIGARH CHAIRMAN PHONES—OFF. : 400920,400921,400937 Extn. 368 RES. : (0571) 402399 TELEX : 564—230 AMU IN FAX ; 91—0571—400528 CONTENTS PAGE ND. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT 1. INTRODUCTION 1-19 2. LIFE SKETCH OF PAUL 20-27 GAUGUIN 3. WORK AND STYLE 28-40 4. INFLUENCE OF PAUL 41-57 GAUGUIN OWN MY WORK 5. CONCLUSION ss-eo INDEX OF PHOTOGRAPHS BIBLIOGRAPHY ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I immensely obliged to my Supervisor Prof. Ashfaq Rizvi whose able guidance and esteemed patronage the dissertation would be given final finishing. -

The Destruction of Art

1 The destruction of art Solvent form examines art and destruction—through objects that have been destroyed (lost in fires, floods, vandalism, or, similarly, those that actively court or represent this destruction, such as Christian Marclay’s Guitar Drag or Chris Burden’s Samson), but also as an undoing process within art that the object challenges through form itself. In this manner, events such as the Momart warehouse fire in 2004 (in which large hold- ings of Young British Artists (YBA) and significant collections of art were destroyed en masse through arson), as well as the events surrounding art thief Stéphane Breitwieser (whose mother destroyed the art he had stolen upon his arrest—putting it down a garbage disposal or dumping it in a nearby canal) are critical events in this book, as they reveal something about art itself. Likewise, it is through these moments of destruction that we might distinguish a solvency within art and discover an operation in which something is made visible at a time when art’s metaphorical undo- ing emerges as oddly literal. Against this overlay, a tendency is mapped whereby individuals attempt to conceptually gather these destroyed or lost objects, to somehow recoup them in their absence. This might be observed through recent projects, such as Jonathan Jones’s Museum of Lost Art, the Tate Modern’s Gallery of Lost Art, or Henri Lefebvre’s text The Missing Pieces; along with exhibitions that position art as destruction, such as Damage Control at the Hirschhorn Museum or Under Destruction by the Swiss Institute in New York. -

"I Am Trying to Put Into These Desolate Figures the Savagery That I See in Them and Which Is in Me Too

"I am trying to put into these desolate figures the savagery that I see in them and which is in me too... Dammit, I want to consult nature as well but I don't want to leave out what I see there and what comes into my mind." SYNOPSIS Paul Gauguin is one of the most significant French artists to be initially schooled in Impressionism, but who broke away from its fascination with the everyday world to pioneer a new style of painting broadly referred to as Symbolism. As the Impressionist movement was culminating in the late 1880s, Gauguin experimented with new color theories and semi-decorative approaches to painting. He famously worked one summer in an intensely colorful style alongside Vincent © The Art Story Foundation – All rights Reserved For more movements, artists and ideas on Modern Art visit www.TheArtStory.org Van Gogh in the south of France, before turning his back entirely on Western society. He had already abandoned a former life as a stockbroker by the time he began traveling regularly to the south Pacific in the early 1890s, where he developed a new style that married everyday observation with mystical symbolism, a style strongly influenced by the popular, so-called "primitive" arts of Africa, Asia, and French Polynesia. Gauguin's rejection of his European family, society, and the Paris art world for a life apart, in the land of the "Other," has come to serve as a romantic example of the artist-as- wandering-mystic. KEY IDEAS After mastering Impressionist methods for depicting the optical experience of nature, Gauguin studied religious communities in rural Brittany and various landscapes in the Caribbean, while also educating himself in the latest French ideas on the subject of painting and color theory (the latter much influenced by recent scientific study into the various, unstable processes of visual perception). -

Paul Gauguin: the Art of Invention July 21—September 15, 2019 Main Exhibition Galleries, East Building

Large Print Labels Paul Gauguin: The Art of Invention July 21—September 15, 2019 Main Exhibition Galleries, East Building Text Panels Paul Gauguin: The Art of Invention Throughout his career Paul Gauguin (1848–1903) was a radically experimental artist. He produced inventive work in a wide range of media including the paintings, sculpture, drawings, prints, and ceramics seen in this exhibition. Gauguin was self-taught and first adopted the then avant-garde Impressionist technique in the 1870s. Thereafter, he pioneered a painting method of flat patterns and strong outlines in the mid-1880s that anticipated 20th-century abstract art. His wood sculptures and hand-molded ceramics also challenged accepted conventions. No other artist of the time pushed artistic boundaries toward abstraction in such a range of materials as Gauguin. Gauguin’s art was deeply influenced by his extensive travels around the world and his experience with a broad range of cultures. Born to a French father and French- Peruvian mother, Gauguin lived in Lima, Peru, as a child. As a young man he spent several years in the French merchant navy, voyaging from Brazil to India to the Arctic Circle. Subsequently, he traveled around France from Paris to Arles to the coast of Brittany. He also briefly lived in Copenhagen, Denmark. Perhaps the most profound impact on Gauguin’s art resulted from his travels to France’s colonies. He spent several months in Martinique in the Caribbean and lived the later years of his life in Tahiti and the Marquesas Islands. In Polynesia, Gauguin formed intimate relationships with several young women while remaining married to, yet estranged from, his Danish wife, Mette. -

The Museum of Modern Art, New York Exhibition Checklist Gauguin: Metamorphoses March 8-June 8, 2014

The Museum of Modern Art, New York Exhibition Checklist Gauguin: Metamorphoses March 8-June 8, 2014 Paul Gauguin, French, 1848–1903 Vase Decorated with Breton Scenes, 1886–1887 Glazed stoneware (thrown by Ernest Chaplet) with gold highlights 11 5/16 x 4 3/4" (28.8 x 12 cm) Royal Museums of Art and History, Brussels Paul Gauguin, French, 1848–1903 Cup Decorated with the Figure of a Bathing Girl, 1887–1888 Glazed stoneware 11 7/16 x 11 7/16" (29 x 29 cm) Dame Jillian Sackler Paul Gauguin, French, 1848–1903 Vase with the Figure of a Girl Bathing Under the Trees, c. 1887–1888 Glazed stoneware with gold highlights 7 1/2 x 5" (19.1 x 12.7 cm) The Kelton Foundation, Los Angeles Paul Gauguin, French, 1848–1903 Leda (Design for a China Plate). Cover illustration for the Volpini Suite, 1889 Zincograph with watercolor and gouache additions on yellow paper Composition: 8 1/16 x 8 1/16" (20.4 x 20.4 cm) Sheet: 11 15/16 x 10 1/4" (30.3 x 26 cm) The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Rogers Fund 03/11/2014 11:44 AM Gauguin: Metamorphoses Page 1 of 43 Gauguin: Metamorphoses Paul Gauguin, French, 1848–1903 Bathers in Brittany from the Volpini Suite, 1889 Zincograph on yellow paper Composition: 9 11/16 x 7 7/8" (24.6 x 20 cm) Sheet: 18 7/8 x 13 3/8" (47.9 x 34 cm) The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Rogers Fund Paul Gauguin, French, 1848–1903 Edward Ancourt, Paris Breton Women Beside a Fence from the Volpini Suite, 1889 Zincograph on yellow paper Composition: 6 9/16 x 8 7/16" (16.7 x 21.4 cm) Sheet: 18 13/16 x 13 3/8" (47.8 x 34 cm) The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. -

Operant Subjectivity the Taste Test: Applying Q Methodology To

Operant Subjectivity: The International Journal of Q Methodology 37/ 1–2 (2014): 72–96, DOI: 10.15133/j.os.2014.006 Operant Subjectivity The International Journal of Q Methodology The Taste Test: Applying Q Methodology to Aesthetic Preference Rachel Somerstein Syracuse University Abstract: The Taste Test examined if people’s aesthetic preferences translate from one medium to another – specifically, if they prefer similar genres of fine-art photography as they do in painting. Twenty-one graduate students in communication completed two separate Q sorts in which they ranked 40 paintings and 40 photographs from “most unappealing” to “most appealing.” The Q sorts were structured according to eight distinct types of art. A brief survey of demographic information and open-ended questions about artistic training and preferences was also used to analyze the data. Introduction It took Thomas Hart Benton a year and a half to plan and execute his mural Social History of the State of Missouri (1936), which he was commissioned to paint in the House lounge of Missouri’s State Capitol (Kammen, 2006, p. 136). The painting, which Benton considered his finest work, attracted mixed reviews. Though the Missouri governor appreciated the mural, others were less sanguine; as a state engineer told a local reporter, “I wouldn’t hang a Benton on my shithouse wall” (Kammen, 2006, p. 137). History is littered with such instances of divisive cultural artifacts. Thus it may come as no surprise that social scientists have attempted to explain aesthetic preference from sundry standpoints, among them viewers’ religious orientation (van Eijck, 2012); socioeconomic, cultural, gender, and age differences (van Eijck 2012 p. -

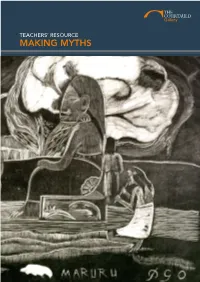

Making Myths Contents

TEACHERS’ RESOURCE MAKING MYTHS CONTENTS 1: MAKING MYTHS: THE STORIES TOLD BY ARTISTS, CURATORS, COLLECTORS AND CONSERVATORS 2: COLLECTING GAUGUIN: CURATOR’S QUESTIONS 3: RE-INVENTING MYTH: FORM AND FUNCTION IN SOME EARLY MODERN ‘MYTHOLOGICAL’ WORKS FROM THE COURTAULD GALLERY 4: MANET, DEGAS, RENOIR AND THE THEATRE OF EVERYDAY LIFE 5: TAKEN AT FACE VALUE? SELF-STAGING AND MYTH-MAKING IN THE WORK OF GAUGUIN AND VAN GOGH 6: THE MATERIAL LANGUAGE OF PAINTINGS: CONSERVATION AND TECHNICAL ART HISTORY 7: REGARDE! FRENCH LANGUAGE RESOURCE: GAUGUIN ET LA POLYNÉSIE 8: GLOSSARY 9: SUGGESTIONS FOR RESEARCH AND PRACTICAL ACTIVITIES IN THE CLASSROOM 10: TEACHING RESOURCE IMAGE CD Compiled and produced by Carolin Levitt and Sarah Green Design by JWDesigns SUGGESTED CURRICULUM LINKS FOR EACH ESSAY ARE MARKED IN RED TERMS REFERRED TO IN THE GLOSSARY ARE MARKED IN BLUE To book a visit to the gallery or to discuss any of the education projects at The Courtauld Gallery please contact: e: [email protected] t: 0207 848 1058 WELCOME The Courtauld Institute of Art runs an exceptional programme of activities suitable for young people, school teachers and members of the public, whatever their age or background. We offer resources which contribute to the understanding, knowledge and enjoyment of art history based upon the world-renowned art collection and the expertise of our students and scholars. I hope the material will prove to be both useful and inspiring. Henrietta Hine Head of Public Programmes The Courtauld Institute of Art This resource offers teachers and their students an opportunity to explore the wealth of The Courtauld Gallery’s permanent collection by expanding on a key idea drawn from our exhibition programme. -

Toward the Modern Era 1870-1914

Toward the Modern Era 1870-1914 Based on Cunningham Chapter 18 The Growing Unrest -Social and Political Revolutions replacing the old monarchies -Scientific and technological advances -Feelings of cheerfulness in the cities of Europe - Belle Epoque – Beautiful Age -superficial as feelings that war would break out -the collapse of the fabric of European civilization – pre-World War I Impressionism • Group of artists rejected by the Parisian Art establishment organized own exhibit which scandalized • One work: Impression: Sunrise by Monet was particularly “scandalous” and lent its name to a new movement – Impressionism • Impressionism became a revolution in art Impressionism • First attempt was to achieve a greater realism –advancing the original ideas of the Renaissance • Impressionists concentrated on the realism of light and color and not form • Desire to reproduce the impression objects made on their eyes –Often we “see” details that are not there or visible because they are usually there or supposed to be there Edouard Manet 1832-1883 -Paris is the center of new artistic activity -Manet shocks the art world and makes possible the Impressionist movement -Style of art (not the subject matter) shows Manet breaking with tradition -Scenes are focused and obscured at the same time The Luncheon on the Grass by Manet • 1863 – Paris • Caused a public outcry – rejected as the Paris Salon exhibition –Rare to have nude females WITH clothed men –Men are indifferent to the women –Figures are NOT 3-D well rounded but flat –Situation is what is important here –Color brilliance A Bar at the Folies-Bergere by Manet • 1882 – London • Style changes from woman to those in the mirror –Sharp outlines and defined forms are replaced by blur of shapes and colors Red Boats at Argenteuil by Claude Monet • 1875 Boston • Combining separate colors to reproduce the effects of light • Monet recorded all the colors of the water and boats and does not blend them –This is what the artist sees NOT what he knows or assumes is there. -

Art As a Lure: the Impact of Canonical Art Imagery on the Cultural Cachet Of

INFORMATION TC3 USERS This mamiscript -bas ken reproduœd from the microfilm master. UMI hlms the text dire* fiom the original or copy submitred. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typeWTiter face, while othea may be fkom aay type of cornputer printer- The qudity of this repdoction is dependent opon the quai@ of the copy mbmitfed. Broken or indistinct print, colored or prquality iuustrations idphotographs, prim bleedtbrough, substandard margins, and improper aIigmnent can adverse&affect reproductio~t In the unlikely. event that the author did not send UMI a complete mamsaïpt and there are mishg pages, these will be noted. Also, if tlflsiiithorized copyright niaterial had to be removeci, a note wiü iadicate the deletion, Oversize matcriais (e.& maps, drawiags, chats) are reproduœd by sectionhg the original beginning at the upper left-hand corner and contmiiiag from Ieft to right in equd sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is hcluded in reduced form at the back of the book Photographs indudeci in the onginai mamÛcript have ken reproduced xerograpbidy in this cow. Higher @ty 6" x 9" black and white photographie prints are avaijabfe for aay photographs or ülustrations appear@ in this copy for an addibonal charge- Contact UMI dire* to order. A Bell & Howeii information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Amor. MI 48106-r3d6USA 313!7614700 800:5214600 University of Alberta Art as a Lure: The Impact of Canonical Art lmagery on the Cultural Cachet of the Advertisement Mary Melinda Pinfold O A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Histov of Art and Design Department of Art and Design Edmonton, Alberta Spring 1998 National Library Bibliothèque nationale 191 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. -

French Painter Paul Gauguin

Modern-day Artistic Reaction: The New York Times Considers “Canceling” French Painter Paul Gauguin By David Walsh Region: USA Global Research, November 29, 2019 Theme: History, Intelligence World Socialist Web Site 25 November 2019 According to Victoria Charles, a biographer of French Post-Impressionist painter Paul Gauguin (1848-1903), the artist died in Atuona, in the Marquesas Islands in French Polynesia, “having lost a futile and fatally exhausting battle with colonial officials, threatened with a ruinous fine and an imprisonment for allegedly instigating the natives to mutiny and slandering the [French] authorities, after a week of acute physical sufferings [from syphilis] endured in utter isolation.” Upon receiving the news of the death “of their old enemy, the bishop and the brigadier of gendarmes—the pillars of the local [French] colonial regime—hastened to demonstrate their fatherly concern for the salvation of the sinner’s soul by having him buried in the sanctified ground of a Catholic cemetery. Only a small group of natives accompanied the body to the grave. There were no funeral speeches, and an inscription on the tombstone was denied to the late artist.” The bishop subsequently wrote in his regular report to Paris: “The only noteworthy event here has been the sudden death of a contemptible individual named Gauguin, a reputed artist but an enemy of God and everything that is decent.” Paul Gauguin, Ta Matete, 1892, Kunstmuseum Basel | 1 Over the course of the next several decades, Gauguin’s importance as an artist became widely recognized. His influence on Henri Matisse, André Derain, Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Fauvism and Cubism was especially significant.