Land Insecurity in Khartoum: When Land Titles Fail to Protect Against Public Predation Alice Franck Translated from the French by Oliver Waine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Estimations of Undisturbed Ground Temperatures Using Numerical and Analytical Modeling

ESTIMATIONS OF UNDISTURBED GROUND TEMPERATURES USING NUMERICAL AND ANALYTICAL MODELING By LU XING Bachelor of Arts/Science in Mechanical Engineering Huazhong University of Science & Technology Wuhan, China 2008 Master of Arts/Science in Mechanical Engineering Oklahoma State University Stillwater, OK, US 2010 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December, 2014 ESTIMATIONS OF UNDISTURBED GROUND TEMPERATURES USING NUMERICAL AND ANALYTICAL MODELING Dissertation Approved: Dr. Jeffrey D. Spitler Dissertation Adviser Dr. Daniel E. Fisher Dr. Afshin J. Ghajar Dr. Richard A. Beier ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Jeffrey D. Spitler, who patiently guided me through the hard times and encouraged me to continue in every stage of this study until it was completed. I greatly appreciate all his efforts in making me a more qualified PhD, an independent researcher, a stronger and better person. Also, I would like to devote my sincere thanks to my parents, Hongda Xing and Chune Mei, who have been with me all the time. Their endless support, unconditional love and patience are the biggest reason for all the successes in my life. To all my good friends, colleagues in the US and in China, who talked to me and were with me during the difficult times. I would like to give many thanks to my committee members, Dr. Daniel E. Fisher, Dr. Afshin J. Ghajar and Dr. Richard A. Beier for their suggestions which helped me to improve my research and dissertation. -

Global Suicide Rates and Climatic Temperature

SocArXiv Preprint: May 25, 2020 Global Suicide Rates and Climatic Temperature Yusuke Arima1* [email protected] Hideki Kikumoto2 [email protected] ABSTRACT Global suicide rates vary by country1, yet the cause of this variability has not yet been explained satisfactorily2,3. In this study, we analyzed averaged suicide rates4 and annual mean temperature in the early 21st century for 183 countries worldwide, and our results suggest that suicide rates vary with climatic temperature. The lowest suicide rates were found for countries with annual mean temperatures of approximately 20 °C. The correlation suicide rate and temperature is much stronger at lower temperatures than at higher temperatures. In the countries with higher temperature, high suicide rates appear with its temperature over about 25 °C. We also investigated the variation in suicide rates with climate based on the Köppen–Geiger climate classification5, and found suicide rates to be low in countries in dry zones regardless of annual mean temperature. Moreover, there were distinct trends in the suicide rates in island countries. Considering these complicating factors, a clear relationship between suicide rates and temperature is evident, for both hot and cold climate zones, in our dataset. Finally, low suicide rates are typically found in countries with annual mean temperatures within the established human thermal comfort range. This suggests that climatic temperature may affect suicide rates globally by effecting either hot or cold thermal stress on the human body. KEYWORDS Suicide rate, Climatic temperature, Human thermal comfort, Köppen–Geiger climate classification Affiliation: 1 Department of Architecture, Polytechnic University of Japan, Tokyo, Japan. -

The Impact of Climate Variability and Conflict on Childhood Diarrhea and Malnutrition in West Africa

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2016 The Impact of Climate Variability and Conflict on Childhood Diarrhea and Malnutrition in West Africa Gillian Dunn Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/765 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] The Impact of Climate Variability and Conflict on Childhood Diarrhea and Malnutrition in West Africa by Gillian Dunn A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Public Health in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Public Health, The City University of New York 2016 © 2016 Gillian Dunn All Rights Reserved ii The Impact of Climate Variability and Conflict on Childhood Diarrhea and Malnutrition in West Africa by Gillian Dunn This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Public Health to satisfy the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Public Health Deborah Balk, PhD Sponsor of Examining Committee Date Signature Denis Nash, PhD Executive Officer, Public Health Date Signature Examining Committee: Glen Johnson, PhD Grace Sembajwe, ScD Emmanuel d’Harcourt, MD THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Dissertation Abstract Title: The Impact of Climate Variability and Conflict on Childhood Diarrhea and Malnutrition in West Africa Author: Gillian Dunn Sponsor: Deborah Balk Objectives: This dissertation aims to contribute to our understanding of how climate variability and armed conflict impacts diarrheal disease and malnutrition among young children in West Africa. -

Nouakchott City Urban Master Plan Development Project in Islamic Republic of Mauritania

Islamic Republic of Mauritania Ministry of Land Use, Urbanization and Habitation (MHUAT) Urban Community of Nouakchott (CUN) Nouakchott City Urban Master Plan Development Project In Islamic Republic of Mauritania Final Report Summary October 2018 Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) RECS International Inc. CTI Engineering International Co., Ltd. PACET Corporation PASCO Corporation EI JR 18-105 Currency equivalents (interbank rates average of April to June 2018) USD 1.00 = MRU 355.049 USD 1.00 = MRO (obsolete) 35.5049 USD 1.00 = JPY 109.889 MRU 1.00 = JPY 3.0464 Source: OANDA, https://www.oanda.com Nouakchott City Urban Master Plan Development Project Final Report Summary Table of Contents Introduction 1 Background ........................................................................................................................... 1 Objectives .............................................................................................................................. 2 Target Area ............................................................................................................................ 2 Target Year ............................................................................................................................. 3 Reports and Other Outputs .................................................................................................... 3 Work Operation Structure ...................................................................................................... 3 Part I: SDAU ............................................................................................................................... -

East Africa Counterterrorism Operation North and West Africa Counterterrorism Operation Lead Inspector General Report to the United States Congress

EAST AFRICA COUNTERTERRORISM OPERATION NORTH AND WEST AFRICA COUNTERTERRORISM OPERATION LEAD INSPECTOR GENERAL REPORT TO THE UNITED STATES CONGRESS JULY 1, 2020‒SEPTEMBER 30, 2020 ABOUT THIS REPORT A 2013 amendment to the Inspector General Act established the Lead Inspector General (Lead IG) framework for oversight of overseas contingency operations and requires that the Lead IG submit quarterly reports to Congress on each active operation. The Chair of the Council of Inspectors General for Integrity and Efficiency designated the DoD Inspector General (IG) as the Lead IG for the East Africa Counterterrorism Operation and the North and West Africa Counterterrorism Operation. The DoS IG is the Associate IG for the operations. The USAID IG participates in oversight of the operations. The Offices of Inspector General (OIG) of the DoD, the DoS, and USAID are referred to in this report as the Lead IG agencies. Other partner agencies also contribute to oversight of the operations. The Lead IG agencies collectively carry out the Lead IG statutory responsibilities to: • Develop a joint strategic plan to conduct comprehensive oversight of the operations. • Ensure independent and effective oversight of programs and operations of the U.S. Government in support of the operations through either joint or individual audits, inspections, investigations, and evaluations. • Report quarterly to Congress and the public on the operations and on activities of the Lead IG agencies. METHODOLOGY To produce this quarterly report, the Lead IG agencies submit requests for information to the DoD, the DoS, USAID, and other Federal agencies about the East Africa Counterterrorism Operation, the North and West Africa Counterterrorism Operation, and related programs. -

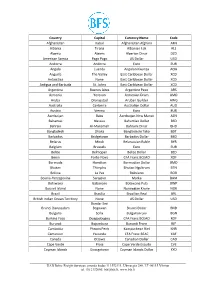

International Currency Codes

Country Capital Currency Name Code Afghanistan Kabul Afghanistan Afghani AFN Albania Tirana Albanian Lek ALL Algeria Algiers Algerian Dinar DZD American Samoa Pago Pago US Dollar USD Andorra Andorra Euro EUR Angola Luanda Angolan Kwanza AOA Anguilla The Valley East Caribbean Dollar XCD Antarctica None East Caribbean Dollar XCD Antigua and Barbuda St. Johns East Caribbean Dollar XCD Argentina Buenos Aires Argentine Peso ARS Armenia Yerevan Armenian Dram AMD Aruba Oranjestad Aruban Guilder AWG Australia Canberra Australian Dollar AUD Austria Vienna Euro EUR Azerbaijan Baku Azerbaijan New Manat AZN Bahamas Nassau Bahamian Dollar BSD Bahrain Al-Manamah Bahraini Dinar BHD Bangladesh Dhaka Bangladeshi Taka BDT Barbados Bridgetown Barbados Dollar BBD Belarus Minsk Belarussian Ruble BYR Belgium Brussels Euro EUR Belize Belmopan Belize Dollar BZD Benin Porto-Novo CFA Franc BCEAO XOF Bermuda Hamilton Bermudian Dollar BMD Bhutan Thimphu Bhutan Ngultrum BTN Bolivia La Paz Boliviano BOB Bosnia-Herzegovina Sarajevo Marka BAM Botswana Gaborone Botswana Pula BWP Bouvet Island None Norwegian Krone NOK Brazil Brasilia Brazilian Real BRL British Indian Ocean Territory None US Dollar USD Bandar Seri Brunei Darussalam Begawan Brunei Dollar BND Bulgaria Sofia Bulgarian Lev BGN Burkina Faso Ouagadougou CFA Franc BCEAO XOF Burundi Bujumbura Burundi Franc BIF Cambodia Phnom Penh Kampuchean Riel KHR Cameroon Yaounde CFA Franc BEAC XAF Canada Ottawa Canadian Dollar CAD Cape Verde Praia Cape Verde Escudo CVE Cayman Islands Georgetown Cayman Islands Dollar KYD _____________________________________________________________________________________________ -

Supplementary Material Barriers and Facilitators to Pre-Exposure

Sexual Health, 2021, 18, 130–39 © CSIRO 2021 https://doi.org/10.1071/SH20175_AC Supplementary Material Barriers and facilitators to pre-exposure prophylaxis among A frican migr ants in high income countries: a systematic review Chido MwatururaA,B,H, Michael TraegerC,D, Christopher LemohE, Mark StooveC,D, Brian PriceA, Alison CoelhoF, Masha MikolaF, Kathleen E. RyanA,D and Edwina WrightA,D,G ADepartment of Infectious Diseases, The Alfred and Central Clinical School, Monash Un iversity, Melbourne, Vic., Australia. BMelbourne Medical School, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Vic., Australia. CSchool of Public Health and Preventative Medicine, Monash University, Melbourne, Vic., Australia. DBurnet Institute, Melbourne, Vic., Australia. EMonash Infectious Diseases, Monash Health, Melbourne, Vi, Auc. stralia. FCentre for Culture, Ethnicity & Health, Melbourne, Vic., Australia. GPeter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Vic., Australia. HCorresponding author. Email: [email protected] File S1 Appendix 1: Syntax Usedr Dat fo abase Searches Appendix 2: Table of Excluded Studies ( n=58) and Reasons for Exclusion Appendix 3: Critical Appraisal of Quantitative Studies Using the ‘ Joanna Briggs Institute Checklist for Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies’ (39) Appendix 4: Critical Appraisal of Qualitative Studies U sing a modified ‘CASP Qualitative C hecklist’ (37) Appendix 5: List of Abbreviations Sexual Health © CSIRO 2021 https://doi.org/10.1071/SH20175_AC Appendix 1: Syntax Used for Database -

Key Officers List (UNCLASSIFIED)

United States Department of State Telephone Directory This customized report includes the following section(s): Key Officers List (UNCLASSIFIED) 9/13/2021 Provided by Global Information Services, A/GIS Cover UNCLASSIFIED Key Officers of Foreign Service Posts Afghanistan FMO Inna Rotenberg ICASS Chair CDR David Millner IMO Cem Asci KABUL (E) Great Massoud Road, (VoIP, US-based) 301-490-1042, Fax No working Fax, INMARSAT Tel 011-873-761-837-725, ISO Aaron Smith Workweek: Saturday - Thursday 0800-1630, Website: https://af.usembassy.gov/ Algeria Officer Name DCM OMS Melisa Woolfolk ALGIERS (E) 5, Chemin Cheikh Bachir Ibrahimi, +213 (770) 08- ALT DIR Tina Dooley-Jones 2000, Fax +213 (23) 47-1781, Workweek: Sun - Thurs 08:00-17:00, CM OMS Bonnie Anglov Website: https://dz.usembassy.gov/ Co-CLO Lilliana Gonzalez Officer Name FM Michael Itinger DCM OMS Allie Hutton HRO Geoff Nyhart FCS Michele Smith INL Patrick Tanimura FM David Treleaven LEGAT James Bolden HRO TDY Ellen Langston MGT Ben Dille MGT Kristin Rockwood POL/ECON Richard Reiter MLO/ODC Andrew Bergman SDO/DATT COL Erik Bauer POL/ECON Roselyn Ramos TREAS Julie Malec SDO/DATT Christopher D'Amico AMB Chargé Ross L Wilson AMB Chargé Gautam Rana CG Ben Ousley Naseman CON Jeffrey Gringer DCM Ian McCary DCM Acting DCM Eric Barbee PAO Daniel Mattern PAO Eric Barbee GSO GSO William Hunt GSO TDY Neil Richter RSO Fernando Matus RSO Gregg Geerdes CLO Christine Peterson AGR Justina Torry DEA Edward (Joe) Kipp CLO Ikram McRiffey FMO Maureen Danzot FMO Aamer Khan IMO Jaime Scarpatti ICASS Chair Jeffrey Gringer IMO Daniel Sweet Albania Angola TIRANA (E) Rruga Stavro Vinjau 14, +355-4-224-7285, Fax +355-4- 223-2222, Workweek: Monday-Friday, 8:00am-4:30 pm. -

10533/1/05 REV 1 GK/Lm 1 DG H I COUNCIL of the EUROPEAN

COUNCIL OF Brussels, 30 June 2005 THE EUROPEAN UNION 10533/1/05 REV 1 VISA 153 COMIX 421 NOTE from: Finnish delegation to: Visa Working Party Subject: Amendment of Annex 18 to the Common Consular Instructions (CCI): table of representation for issuing uniform visas (doc. 11272/2/04 VISA 137 COMIX 465 REV 2) The Finnish delegation wishes to inform delegations that for the purpose of issuing visas, Portugal has been representing Finland in Bissau (Guinea-Bissau) and Dili (Timor-Leste) since 4 April 2005. Italy has been representing Finland in Jerevan (Armenia) as of 21 April 2005. In view of the upcoming 10th World Athletics Championships in Helsinki, which are taking place between 6 and 14 August 2005, the following Member States will be representing Finland on a temporary basis between 1 June and 15 August 2005: · Portugal: in São Tomé (São Tomé and Principe). · Italy: in Bagdad (Iraq). · Germany: in Askhabad (Turkmenistan), Chisinau (Moldova), Kingston (Jamaica), Minsk (Belarus) and Ulan Bator (Mongolia). · Spain: in Libreville (Gabon), Malabo (Equatorial Guinea) and Port-au-Prince (Haiti). 10533/1/05 REV 1 GK/lm 1 DG H I EN · France: in Antananarivo (Madagascar), Lomé (Togo), Phnom Penh (Cambodia), Port Louis (Mauritius), Port Moresby (Papua New Guinea), Port Vila (Vanuatu), Suva (Fiji), Victoria (Seychelles), Yaoundé (Cameroon), Bamako (Mali), Bangui (Central African Republic), Castries (Saint Lucia), Conakry (Guinea), Djibouti (Djibouti), Moroni (Comoros), N'Djamena (Chad), Niamey (Niger), Nouakchott (Mauritania), Praia (Cape Verde), Rangoon (Myanmar) and Vientiane (Laos). · Norway: in Harare (Zimbabwe), Lilongwe (Malawi), Luanda (Angola) and Skopje (Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia). · Belgium: in Bujumbura (Burundi), Cotonou (Benin) and Kigali (Rwanda). -

Destinations Offered Via Interline Services

d Destinations offered via Interline services Cargolux Airlines International S.A. Interline Department [email protected] Search for your destination This document is purely indicative and for informational purpose only. It should not be construed as creating any contractual obligation from Cargolux Airlines International S.A., who reserves the right to alter or modify this document or any available destination without prior notice. d European Destinations ATH (Athens, Greece) LCA (Larnaca, Cyprus) BEG (Belgrade, Serbia) LIS (Lisbon, Portugal) BTS (Bratislava, Slovakia) LJU (Ljubljana, Slovenia) DME (Moscow, Russia) LNZ (Linz, Austria) DNK (Dnipropetrovsk, Ukraine) LWO (Lviv, Ukraine) EMA (East Midlands, UK) ODS (Odessa, Ukraine) FAO (Faro, Portugal) OPO (Porto, Portugal) HRK (Kharkiv, Ukraine) SKP (Skopje, Macedonia) KBP (Boryspil , Ukraine) SVO (Moscow, Russia) KEF (Reykjavík, Iceland) ZAG (Zagreb, Croatia) KIV (Chisinau, Moldova) This document is purely indicative and for informational purpose only. It should not be construed as creating any contractual obligation from Cargolux Airlines International S.A., who reserves the right to alter or modify this document or any available destination without prior notice. d South America & Caribbean (via Miami) ANU (Osbourn, Antigua and Barbuda) PBM (Paramaribo, Suriname) AUA (Oranjestad, Aruba) POS (Piarco, Trinidad and Tobago) BAQ (Barranquilla, Colombia) PTY (Panama City, Panama) BGI (Seawell, Barbados) RNG (Rangely, Colorado) BZE (Ladyville, Belize) SAP -

The Case of Nouakchott

New Approach to Measure Urban Poverty: THE CASE OF NOUAKCHOTT Paper presented at the XXV111 International Population Conference,. Cape Town, South Africa 29th of October- 4th of November 2017 Dr. Osman Nour Arab Urban Development Institute (AUDI) August, 2017 1 / 18 New Approach to Measure Urban Poverty: THE CASE OF NOUAKCHOTT Dr. Osman Nour, Arab Urban Development Institute (AUDI) [email protected]; [email protected] I-Introduction and Objectives of the Study: Poverty as a multidimensional phenomenon is perhaps most revealed in urban areas. Urban Poverty is not only characterized by inadequate income, but also by lack of adequate asset base, dwelling, provision of public infrastructure. In addition access to social services such as education and health can be scarce. Poor urban households often suffer limited social safety nets, powerlessness within political system (UN Habitat, 2003). The most common quantitative approach to measure urban poverty alone can underestimate urban poverty, because it does not take into account the extra cost of urban living, such as housing, education, health, electricity, water, transport, and other services. Therefore, income alone cannot capture the many dimensions of urban poverty. Several poverty measure have been introduced to estimate urban poverty, such as "Unsatisfied Basic Needs" (UBN), "Income Poverty Line" (IPL), and others, based on various characteristics of household pertaining to its dwelling conditions, ownership of assets, demographic characteristics, educational level, and employment of household's members. Recently, the Arab Urban Development Institute (AUDI) and the UN Economic and Social Commission for West Asia (ESCWA) have constructed an index to measure Urban Poverty. The main purpose of the index was to measure urban poverty in a simplified and straight forward manner through using short list of highly indicative variables. -

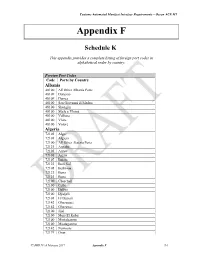

Appendix F – Schedule K

Customs Automated Manifest Interface Requirements – Ocean ACE M1 Appendix F Schedule K This appendix provides a complete listing of foreign port codes in alphabetical order by country. Foreign Port Codes Code Ports by Country Albania 48100 All Other Albania Ports 48109 Durazzo 48109 Durres 48100 San Giovanni di Medua 48100 Shengjin 48100 Skele e Vlores 48100 Vallona 48100 Vlore 48100 Volore Algeria 72101 Alger 72101 Algiers 72100 All Other Algeria Ports 72123 Annaba 72105 Arzew 72105 Arziw 72107 Bejaia 72123 Beni Saf 72105 Bethioua 72123 Bona 72123 Bone 72100 Cherchell 72100 Collo 72100 Dellys 72100 Djidjelli 72101 El Djazair 72142 Ghazaouet 72142 Ghazawet 72100 Jijel 72100 Mers El Kebir 72100 Mestghanem 72100 Mostaganem 72142 Nemours 72179 Oran CAMIR V1.4 February 2017 Appendix F F-1 Customs Automated Manifest Interface Requirements – Ocean ACE M1 72189 Skikda 72100 Tenes 72179 Wahran American Samoa 95101 Pago Pago Harbor Angola 76299 All Other Angola Ports 76299 Ambriz 76299 Benguela 76231 Cabinda 76299 Cuio 76274 Lobito 76288 Lombo 76288 Lombo Terminal 76278 Luanda 76282 Malongo Oil Terminal 76279 Namibe 76299 Novo Redondo 76283 Palanca Terminal 76288 Port Lombo 76299 Porto Alexandre 76299 Porto Amboim 76281 Soyo Oil Terminal 76281 Soyo-Quinfuquena term. 76284 Takula 76284 Takula Terminal 76299 Tombua Anguilla 24821 Anguilla 24823 Sombrero Island Antigua 24831 Parham Harbour, Antigua 24831 St. John's, Antigua Argentina 35700 Acevedo 35700 All Other Argentina Ports 35710 Bagual 35701 Bahia Blanca 35705 Buenos Aires 35703 Caleta Cordova 35703 Caleta Olivares 35703 Caleta Olivia 35711 Campana 35702 Comodoro Rivadavia 35700 Concepcion del Uruguay 35700 Diamante 35700 Ibicuy CAMIR V1.4 February 2017 Appendix F F-2 Customs Automated Manifest Interface Requirements – Ocean ACE M1 35737 La Plata 35740 Madryn 35739 Mar del Plata 35741 Necochea 35779 Pto.