Khartoum: City Scoping Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Köppen Signatures” of Fossil Plant Assemblages for Effective Heat Transport of Gulf Stream to Subarctic North Atlantic During Miocene Cooling

Biogeosciences, 10, 7927–7942, 2013 Open Access www.biogeosciences.net/10/7927/2013/ doi:10.5194/bg-10-7927-2013 Biogeosciences © Author(s) 2013. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Evidence from “Köppen signatures” of fossil plant assemblages for effective heat transport of Gulf Stream to subarctic North Atlantic during Miocene cooling T. Denk1, G. W. Grimm1, F. Grímsson2, and R. Zetter2 1Swedish Museum of Natural History, Department of Palaeobiology, Box 50007, 10405 Stockholm, Sweden 2University of Vienna, Department of Palaeontology, Althanstrasse 14, 1090 Vienna, Austria Correspondence to: T. Denk ([email protected]) Received: 8 July 2013 – Published in Biogeosciences Discuss.: 15 August 2013 Revised: 29 October 2013 – Accepted: 2 November 2013 – Published: 6 December 2013 Abstract. Shallowing of the Panama Sill and the closure 1 Introduction of the Central American Seaway initiated the modern Loop Current–Gulf Stream circulation pattern during the Miocene, The Mid-Miocene Climatic Optimum (MMCO) at 17–15 but no direct evidence has yet been provided for effec- million years (Myr) was the last phase of markedly warm cli- tive heat transport to the northern North Atlantic during mate in the Cenozoic (Zachos et al., 2001). The MMCO was that time. Climatic signals from 11 precisely dated plant- followed by the Mid-Miocene Climate Transition (MMCT) bearing sedimentary rock formations in Iceland, spanning at 14.2–13.8 Myr correlated with the growth of the East 15–0.8 million years (Myr), resolve the impacts of the devel- Antarctic Ice Sheet (Shevenell et al., 2004). In the Northern oping Miocene global thermohaline circulation on terrestrial Hemisphere this cooling is reflected by continuous sea ice in vegetation in the subarctic North Atlantic region. -

Immigrant Visa Issuances by Post June 2021 (FY 2021)

Immigrant Visa Issuances by Post June 2021 (FY 2021) Post Visa Class Issuances Abidjan CR1 10 Abidjan DV 8 Abidjan F1 5 Abidjan F2B 1 Abidjan F4 8 Abidjan FX 33 Abidjan IR1 10 Abidjan IR2 18 Abidjan IR5 14 Abu Dhabi CR1 39 Abu Dhabi DV 29 Abu Dhabi E1 1 Abu Dhabi E3 81 Abu Dhabi F1 14 Abu Dhabi F2B 7 Abu Dhabi F3 12 Abu Dhabi F4 60 Abu Dhabi FX 16 Abu Dhabi I5 3 Abu Dhabi IR1 89 Abu Dhabi IR2 17 Abu Dhabi IR5 84 Abu Dhabi SB1 9 Abu Dhabi SE 4 Accra CR1 1 Accra E3 15 Accra F1 15 Accra F2B 4 Accra F3 22 Accra F4 13 Accra FX 23 Accra IR1 35 Accra IR2 48 Accra IR5 41 Accra SB1 9 Accra SE 32 Addis Ababa CR1 17 Addis Ababa DV 9 Addis Ababa E1 1 Addis Ababa F1 12 Addis Ababa F2B 13 Addis Ababa F3 5 Page 1 of 34 Immigrant Visa Issuances by Post June 2021 (FY 2021) Post Visa Class Issuances Addis Ababa FX 125 Addis Ababa IR1 90 Addis Ababa IR2 83 Addis Ababa IR5 47 Addis Ababa SB1 4 Addis Ababa SE 57 AIT Taipei DV 2 AIT Taipei E1 6 AIT Taipei E2 18 AIT Taipei E3 5 AIT Taipei EW 1 AIT Taipei F1 15 AIT Taipei F2B 1 AIT Taipei F3 12 AIT Taipei F4 92 AIT Taipei FX 36 AIT Taipei I5 33 AIT Taipei IR1 11 AIT Taipei IR2 6 AIT Taipei IR3 7 AIT Taipei IR5 30 AIT Taipei SB1 30 Algiers CR1 26 Algiers DV 45 Algiers F4 2 Algiers FX 23 Algiers IR1 42 Algiers IR2 9 Algiers IR5 30 Algiers SE 5 Almaty CR1 1 Almaty DV 134 Almaty E3 4 Almaty F1 1 Almaty F2B 1 Almaty FX 49 Almaty IB1 1 Almaty IR1 4 Almaty IR2 6 Almaty IR5 58 Amman CR1 8 Amman CR2 1 Page 2 of 34 Immigrant Visa Issuances by Post June 2021 (FY 2021) Post Visa Class Issuances Amman DV 57 Amman E2 6 Amman -

Estimations of Undisturbed Ground Temperatures Using Numerical and Analytical Modeling

ESTIMATIONS OF UNDISTURBED GROUND TEMPERATURES USING NUMERICAL AND ANALYTICAL MODELING By LU XING Bachelor of Arts/Science in Mechanical Engineering Huazhong University of Science & Technology Wuhan, China 2008 Master of Arts/Science in Mechanical Engineering Oklahoma State University Stillwater, OK, US 2010 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December, 2014 ESTIMATIONS OF UNDISTURBED GROUND TEMPERATURES USING NUMERICAL AND ANALYTICAL MODELING Dissertation Approved: Dr. Jeffrey D. Spitler Dissertation Adviser Dr. Daniel E. Fisher Dr. Afshin J. Ghajar Dr. Richard A. Beier ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Jeffrey D. Spitler, who patiently guided me through the hard times and encouraged me to continue in every stage of this study until it was completed. I greatly appreciate all his efforts in making me a more qualified PhD, an independent researcher, a stronger and better person. Also, I would like to devote my sincere thanks to my parents, Hongda Xing and Chune Mei, who have been with me all the time. Their endless support, unconditional love and patience are the biggest reason for all the successes in my life. To all my good friends, colleagues in the US and in China, who talked to me and were with me during the difficult times. I would like to give many thanks to my committee members, Dr. Daniel E. Fisher, Dr. Afshin J. Ghajar and Dr. Richard A. Beier for their suggestions which helped me to improve my research and dissertation. -

Global Suicide Rates and Climatic Temperature

SocArXiv Preprint: May 25, 2020 Global Suicide Rates and Climatic Temperature Yusuke Arima1* [email protected] Hideki Kikumoto2 [email protected] ABSTRACT Global suicide rates vary by country1, yet the cause of this variability has not yet been explained satisfactorily2,3. In this study, we analyzed averaged suicide rates4 and annual mean temperature in the early 21st century for 183 countries worldwide, and our results suggest that suicide rates vary with climatic temperature. The lowest suicide rates were found for countries with annual mean temperatures of approximately 20 °C. The correlation suicide rate and temperature is much stronger at lower temperatures than at higher temperatures. In the countries with higher temperature, high suicide rates appear with its temperature over about 25 °C. We also investigated the variation in suicide rates with climate based on the Köppen–Geiger climate classification5, and found suicide rates to be low in countries in dry zones regardless of annual mean temperature. Moreover, there were distinct trends in the suicide rates in island countries. Considering these complicating factors, a clear relationship between suicide rates and temperature is evident, for both hot and cold climate zones, in our dataset. Finally, low suicide rates are typically found in countries with annual mean temperatures within the established human thermal comfort range. This suggests that climatic temperature may affect suicide rates globally by effecting either hot or cold thermal stress on the human body. KEYWORDS Suicide rate, Climatic temperature, Human thermal comfort, Köppen–Geiger climate classification Affiliation: 1 Department of Architecture, Polytechnic University of Japan, Tokyo, Japan. -

The Foreign Military Presence in the Horn of Africa Region

SIPRI Background Paper April 2019 THE FOREIGN MILITARY SUMMARY w The Horn of Africa is PRESENCE IN THE HORN OF undergoing far-reaching changes in its external security AFRICA REGION environment. A wide variety of international security actors— from Europe, the United States, neil melvin the Middle East, the Gulf, and Asia—are currently operating I. Introduction in the region. As a result, the Horn of Africa has experienced The Horn of Africa region has experienced a substantial increase in the a proliferation of foreign number and size of foreign military deployments since 2001, especially in the military bases and a build-up of 1 past decade (see annexes 1 and 2 for an overview). A wide range of regional naval forces. The external and international security actors are currently operating in the Horn and the militarization of the Horn poses foreign military installations include land-based facilities (e.g. bases, ports, major questions for the future airstrips, training camps, semi-permanent facilities and logistics hubs) and security and stability of the naval forces on permanent or regular deployment.2 The most visible aspect region. of this presence is the proliferation of military facilities in littoral areas along This SIPRI Background the Red Sea and the Horn of Africa.3 However, there has also been a build-up Paper is the first of three papers of naval forces, notably around the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, at the entrance to devoted to the new external the Red Sea and in the Gulf of Aden. security politics of the Horn of This SIPRI Background Paper maps the foreign military presence in the Africa. -

The Impact of Climate Variability and Conflict on Childhood Diarrhea and Malnutrition in West Africa

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2016 The Impact of Climate Variability and Conflict on Childhood Diarrhea and Malnutrition in West Africa Gillian Dunn Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/765 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] The Impact of Climate Variability and Conflict on Childhood Diarrhea and Malnutrition in West Africa by Gillian Dunn A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Public Health in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Public Health, The City University of New York 2016 © 2016 Gillian Dunn All Rights Reserved ii The Impact of Climate Variability and Conflict on Childhood Diarrhea and Malnutrition in West Africa by Gillian Dunn This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Public Health to satisfy the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Public Health Deborah Balk, PhD Sponsor of Examining Committee Date Signature Denis Nash, PhD Executive Officer, Public Health Date Signature Examining Committee: Glen Johnson, PhD Grace Sembajwe, ScD Emmanuel d’Harcourt, MD THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Dissertation Abstract Title: The Impact of Climate Variability and Conflict on Childhood Diarrhea and Malnutrition in West Africa Author: Gillian Dunn Sponsor: Deborah Balk Objectives: This dissertation aims to contribute to our understanding of how climate variability and armed conflict impacts diarrheal disease and malnutrition among young children in West Africa. -

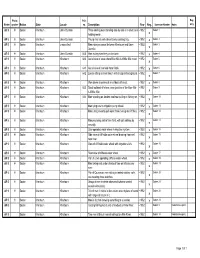

State Locale Description Year Neg. AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Umm Durmān Three Smiling Men Standing Side by Side in Market, One Hold

Photo- Print Neg. Binder grapher Nation State Locale no. Description Year Neg. Sorenson Number Notes only AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Umm Durmān Three smiling men standing side by side in market, one ~1952 Sudan 1 x holding melon. AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Umm Durmān Young man at work decoratively painting tray. ~1952 x Sudan 2 AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum unspecified Man riding on camel between Khartoum and Umm ~1952 Sudan 3 x Durmān. AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Umm Durmān 645 Men exiting river ferry on to shore. ~1952 x Sudan 4 AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Khartoum 640 Aerial view of area where Blue Nile & White Nile meet. ~1952 Sudan 5 x AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Khartoum 641 Aerial view of riverside farm fields. ~1952 x Sudan 6 AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Khartoum 642 Locals sitting on river beach with bridge in background. ~1952 Sudan 7 x AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Khartoum View down shoreline of small boat off coast. ~1952 x Sudan 8 AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Khartoum 643 Small sailboat off shore, near junction of the Blue Nile ~1952 Sudan 9 x & White Nile. AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Khartoum 644 Man standing on docked row boat pulling in fishing net. ~1952 Sudan 10 x AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Khartoum Man tying cow to irrigation pump wheel. ~1952 x Sudan 11 AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Khartoum Man using levee to pull water from river up to cliff face. ~1952 Sudan 12 x AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Khartoum Man preparing soil in farm field, with girl walking by ~1952 Sudan 13 x casually. -

The Stable Isotope Characteristics of Precipitation in the Middle East

water Article The Stable Isotope Characteristics of Precipitation in the Middle East Highlighting the Link between the Köppen Climate Classifications and the δ18O and δ2H Values of Precipitation Mojtaba Heydarizad 1, Luis Gimeno 1,*, Rogert Sorí 1,2 , Foad Minaei 3,4 and Javad Eskandari Mayvan 5 1 Centro de Investigación Mariña, Environmental Physics Laboratory (EPhysLab), Campus As Lagoas s/n, Universidade de Vigo, 32004 Ourense, Spain; [email protected] (M.H.); [email protected] (R.S.) 2 Instituto Dom Luiz (IDL), Faculdade de Ciências, Universidade de Lisboa, 1749-016 Lisboa, Portugal 3 Department of Geography, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Mashhad 917794883, Iran; [email protected] 4 Geographic Information Science/System and Remote Sensing Laboratory (GISSRS. Lab), Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Mashhad 9177794883, Iran 5 Regional Water Company of Khorasan Razavi, Mashhad 9185916196, Iran; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The Middle East is faced with a water shortage crisis due to its semiarid and arid climate. In this paper, precipitation as an important part of the water cycle was evaluated in 43 stations across the Middle East using the stable isotope technique to study the parameters which influence the stable isotope content of precipitation. First, the stepwise regression model was applied to determine the Citation: Heydarizad, M.; main geographical and climatological factors affecting the stable isotopes in precipitation. Secondly, Gimeno, L.; Sorí, R.; Minaei, F.; the stepwise model was also used to simulate the stable isotope values in precipitation. Furthermore, Mayvan, J.E. The Stable Isotope due to the notable climatic variations across the Middle East, the precipitation sampling stations Characteristics of Precipitation in the Middle East Highlighting the Link were classified into six groups based on the Köppen climate zones. -

Nouakchott City Urban Master Plan Development Project in Islamic Republic of Mauritania

Islamic Republic of Mauritania Ministry of Land Use, Urbanization and Habitation (MHUAT) Urban Community of Nouakchott (CUN) Nouakchott City Urban Master Plan Development Project In Islamic Republic of Mauritania Final Report Summary October 2018 Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) RECS International Inc. CTI Engineering International Co., Ltd. PACET Corporation PASCO Corporation EI JR 18-105 Currency equivalents (interbank rates average of April to June 2018) USD 1.00 = MRU 355.049 USD 1.00 = MRO (obsolete) 35.5049 USD 1.00 = JPY 109.889 MRU 1.00 = JPY 3.0464 Source: OANDA, https://www.oanda.com Nouakchott City Urban Master Plan Development Project Final Report Summary Table of Contents Introduction 1 Background ........................................................................................................................... 1 Objectives .............................................................................................................................. 2 Target Area ............................................................................................................................ 2 Target Year ............................................................................................................................. 3 Reports and Other Outputs .................................................................................................... 3 Work Operation Structure ...................................................................................................... 3 Part I: SDAU ............................................................................................................................... -

Egypt Vs. Algeria – the Nasty Politics of Football

Centro de Estudios y Documentación InternacionalesCentro de Barcelona opiniónCIDOB EGYPT VS. ALGERIA – THE NASTY 52 POLITICS OF FOOTBALL DECEMBER 2009 Francis Ghilès Senior Researcher, CIDOB n Thursday 12th November the bus ferrying the Algerian national football team from Cairo airport to the hotel was stoned by Egyptians – the police did not intervene before a number of players were seriously wounded, Osome even needed stitches. The Pharaohs won 2-0 against the Fennecs (desert fox) thus forcing a play- off which was to be played in the capital of Sudan, Khartoum, on 18th November. The outcome of that match would decide which team would qualify to represent Africa for the finals of the World Cup due in South Africa next year. Ugly incidents occurred between supporters of both teams after the first match which spread to three countries in the run up to the second match. Reckless reporting fanned by Egyptian and Algerian political leaders resulted in large scale demonstrations in Algiers when the Algerian popular newspaper Chourouk reported one Algerian fan had died – it later turned out he had fainted. President Mubarak’s sons joined the fray: on Egyptian television they attacked Algerians for being terrorists. Blogs meanwhile went into overdrive, Algerian bloggers promising to avenge the blood of their brother “killed” in Cairo, Egyp- tians sneering at Algerians for having been colonised by the French for 132 years. The Algerian authorities meanwhile slapped a $600m tax bill on Orascom, the Egyptian company which has a high profile in Algeria and whose headquarters were thrashed by crowds of Algerian supporters. -

East Africa Counterterrorism Operation North and West Africa Counterterrorism Operation Lead Inspector General Report to the United States Congress

EAST AFRICA COUNTERTERRORISM OPERATION NORTH AND WEST AFRICA COUNTERTERRORISM OPERATION LEAD INSPECTOR GENERAL REPORT TO THE UNITED STATES CONGRESS JULY 1, 2020‒SEPTEMBER 30, 2020 ABOUT THIS REPORT A 2013 amendment to the Inspector General Act established the Lead Inspector General (Lead IG) framework for oversight of overseas contingency operations and requires that the Lead IG submit quarterly reports to Congress on each active operation. The Chair of the Council of Inspectors General for Integrity and Efficiency designated the DoD Inspector General (IG) as the Lead IG for the East Africa Counterterrorism Operation and the North and West Africa Counterterrorism Operation. The DoS IG is the Associate IG for the operations. The USAID IG participates in oversight of the operations. The Offices of Inspector General (OIG) of the DoD, the DoS, and USAID are referred to in this report as the Lead IG agencies. Other partner agencies also contribute to oversight of the operations. The Lead IG agencies collectively carry out the Lead IG statutory responsibilities to: • Develop a joint strategic plan to conduct comprehensive oversight of the operations. • Ensure independent and effective oversight of programs and operations of the U.S. Government in support of the operations through either joint or individual audits, inspections, investigations, and evaluations. • Report quarterly to Congress and the public on the operations and on activities of the Lead IG agencies. METHODOLOGY To produce this quarterly report, the Lead IG agencies submit requests for information to the DoD, the DoS, USAID, and other Federal agencies about the East Africa Counterterrorism Operation, the North and West Africa Counterterrorism Operation, and related programs. -

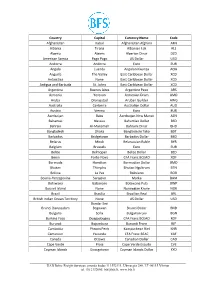

International Currency Codes

Country Capital Currency Name Code Afghanistan Kabul Afghanistan Afghani AFN Albania Tirana Albanian Lek ALL Algeria Algiers Algerian Dinar DZD American Samoa Pago Pago US Dollar USD Andorra Andorra Euro EUR Angola Luanda Angolan Kwanza AOA Anguilla The Valley East Caribbean Dollar XCD Antarctica None East Caribbean Dollar XCD Antigua and Barbuda St. Johns East Caribbean Dollar XCD Argentina Buenos Aires Argentine Peso ARS Armenia Yerevan Armenian Dram AMD Aruba Oranjestad Aruban Guilder AWG Australia Canberra Australian Dollar AUD Austria Vienna Euro EUR Azerbaijan Baku Azerbaijan New Manat AZN Bahamas Nassau Bahamian Dollar BSD Bahrain Al-Manamah Bahraini Dinar BHD Bangladesh Dhaka Bangladeshi Taka BDT Barbados Bridgetown Barbados Dollar BBD Belarus Minsk Belarussian Ruble BYR Belgium Brussels Euro EUR Belize Belmopan Belize Dollar BZD Benin Porto-Novo CFA Franc BCEAO XOF Bermuda Hamilton Bermudian Dollar BMD Bhutan Thimphu Bhutan Ngultrum BTN Bolivia La Paz Boliviano BOB Bosnia-Herzegovina Sarajevo Marka BAM Botswana Gaborone Botswana Pula BWP Bouvet Island None Norwegian Krone NOK Brazil Brasilia Brazilian Real BRL British Indian Ocean Territory None US Dollar USD Bandar Seri Brunei Darussalam Begawan Brunei Dollar BND Bulgaria Sofia Bulgarian Lev BGN Burkina Faso Ouagadougou CFA Franc BCEAO XOF Burundi Bujumbura Burundi Franc BIF Cambodia Phnom Penh Kampuchean Riel KHR Cameroon Yaounde CFA Franc BEAC XAF Canada Ottawa Canadian Dollar CAD Cape Verde Praia Cape Verde Escudo CVE Cayman Islands Georgetown Cayman Islands Dollar KYD _____________________________________________________________________________________________