Internal Displacement, Urbanization and Humanitarian Action in Abidjan, Khartoum and Mogadishu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Köppen Signatures” of Fossil Plant Assemblages for Effective Heat Transport of Gulf Stream to Subarctic North Atlantic During Miocene Cooling

Biogeosciences, 10, 7927–7942, 2013 Open Access www.biogeosciences.net/10/7927/2013/ doi:10.5194/bg-10-7927-2013 Biogeosciences © Author(s) 2013. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Evidence from “Köppen signatures” of fossil plant assemblages for effective heat transport of Gulf Stream to subarctic North Atlantic during Miocene cooling T. Denk1, G. W. Grimm1, F. Grímsson2, and R. Zetter2 1Swedish Museum of Natural History, Department of Palaeobiology, Box 50007, 10405 Stockholm, Sweden 2University of Vienna, Department of Palaeontology, Althanstrasse 14, 1090 Vienna, Austria Correspondence to: T. Denk ([email protected]) Received: 8 July 2013 – Published in Biogeosciences Discuss.: 15 August 2013 Revised: 29 October 2013 – Accepted: 2 November 2013 – Published: 6 December 2013 Abstract. Shallowing of the Panama Sill and the closure 1 Introduction of the Central American Seaway initiated the modern Loop Current–Gulf Stream circulation pattern during the Miocene, The Mid-Miocene Climatic Optimum (MMCO) at 17–15 but no direct evidence has yet been provided for effec- million years (Myr) was the last phase of markedly warm cli- tive heat transport to the northern North Atlantic during mate in the Cenozoic (Zachos et al., 2001). The MMCO was that time. Climatic signals from 11 precisely dated plant- followed by the Mid-Miocene Climate Transition (MMCT) bearing sedimentary rock formations in Iceland, spanning at 14.2–13.8 Myr correlated with the growth of the East 15–0.8 million years (Myr), resolve the impacts of the devel- Antarctic Ice Sheet (Shevenell et al., 2004). In the Northern oping Miocene global thermohaline circulation on terrestrial Hemisphere this cooling is reflected by continuous sea ice in vegetation in the subarctic North Atlantic region. -

Immigrant Visa Issuances by Post June 2021 (FY 2021)

Immigrant Visa Issuances by Post June 2021 (FY 2021) Post Visa Class Issuances Abidjan CR1 10 Abidjan DV 8 Abidjan F1 5 Abidjan F2B 1 Abidjan F4 8 Abidjan FX 33 Abidjan IR1 10 Abidjan IR2 18 Abidjan IR5 14 Abu Dhabi CR1 39 Abu Dhabi DV 29 Abu Dhabi E1 1 Abu Dhabi E3 81 Abu Dhabi F1 14 Abu Dhabi F2B 7 Abu Dhabi F3 12 Abu Dhabi F4 60 Abu Dhabi FX 16 Abu Dhabi I5 3 Abu Dhabi IR1 89 Abu Dhabi IR2 17 Abu Dhabi IR5 84 Abu Dhabi SB1 9 Abu Dhabi SE 4 Accra CR1 1 Accra E3 15 Accra F1 15 Accra F2B 4 Accra F3 22 Accra F4 13 Accra FX 23 Accra IR1 35 Accra IR2 48 Accra IR5 41 Accra SB1 9 Accra SE 32 Addis Ababa CR1 17 Addis Ababa DV 9 Addis Ababa E1 1 Addis Ababa F1 12 Addis Ababa F2B 13 Addis Ababa F3 5 Page 1 of 34 Immigrant Visa Issuances by Post June 2021 (FY 2021) Post Visa Class Issuances Addis Ababa FX 125 Addis Ababa IR1 90 Addis Ababa IR2 83 Addis Ababa IR5 47 Addis Ababa SB1 4 Addis Ababa SE 57 AIT Taipei DV 2 AIT Taipei E1 6 AIT Taipei E2 18 AIT Taipei E3 5 AIT Taipei EW 1 AIT Taipei F1 15 AIT Taipei F2B 1 AIT Taipei F3 12 AIT Taipei F4 92 AIT Taipei FX 36 AIT Taipei I5 33 AIT Taipei IR1 11 AIT Taipei IR2 6 AIT Taipei IR3 7 AIT Taipei IR5 30 AIT Taipei SB1 30 Algiers CR1 26 Algiers DV 45 Algiers F4 2 Algiers FX 23 Algiers IR1 42 Algiers IR2 9 Algiers IR5 30 Algiers SE 5 Almaty CR1 1 Almaty DV 134 Almaty E3 4 Almaty F1 1 Almaty F2B 1 Almaty FX 49 Almaty IB1 1 Almaty IR1 4 Almaty IR2 6 Almaty IR5 58 Amman CR1 8 Amman CR2 1 Page 2 of 34 Immigrant Visa Issuances by Post June 2021 (FY 2021) Post Visa Class Issuances Amman DV 57 Amman E2 6 Amman -

The Foreign Military Presence in the Horn of Africa Region

SIPRI Background Paper April 2019 THE FOREIGN MILITARY SUMMARY w The Horn of Africa is PRESENCE IN THE HORN OF undergoing far-reaching changes in its external security AFRICA REGION environment. A wide variety of international security actors— from Europe, the United States, neil melvin the Middle East, the Gulf, and Asia—are currently operating I. Introduction in the region. As a result, the Horn of Africa has experienced The Horn of Africa region has experienced a substantial increase in the a proliferation of foreign number and size of foreign military deployments since 2001, especially in the military bases and a build-up of 1 past decade (see annexes 1 and 2 for an overview). A wide range of regional naval forces. The external and international security actors are currently operating in the Horn and the militarization of the Horn poses foreign military installations include land-based facilities (e.g. bases, ports, major questions for the future airstrips, training camps, semi-permanent facilities and logistics hubs) and security and stability of the naval forces on permanent or regular deployment.2 The most visible aspect region. of this presence is the proliferation of military facilities in littoral areas along This SIPRI Background the Red Sea and the Horn of Africa.3 However, there has also been a build-up Paper is the first of three papers of naval forces, notably around the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, at the entrance to devoted to the new external the Red Sea and in the Gulf of Aden. security politics of the Horn of This SIPRI Background Paper maps the foreign military presence in the Africa. -

State Locale Description Year Neg. AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Umm Durmān Three Smiling Men Standing Side by Side in Market, One Hold

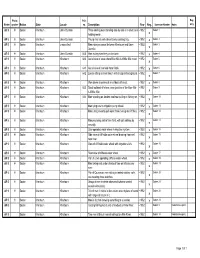

Photo- Print Neg. Binder grapher Nation State Locale no. Description Year Neg. Sorenson Number Notes only AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Umm Durmān Three smiling men standing side by side in market, one ~1952 Sudan 1 x holding melon. AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Umm Durmān Young man at work decoratively painting tray. ~1952 x Sudan 2 AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum unspecified Man riding on camel between Khartoum and Umm ~1952 Sudan 3 x Durmān. AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Umm Durmān 645 Men exiting river ferry on to shore. ~1952 x Sudan 4 AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Khartoum 640 Aerial view of area where Blue Nile & White Nile meet. ~1952 Sudan 5 x AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Khartoum 641 Aerial view of riverside farm fields. ~1952 x Sudan 6 AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Khartoum 642 Locals sitting on river beach with bridge in background. ~1952 Sudan 7 x AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Khartoum View down shoreline of small boat off coast. ~1952 x Sudan 8 AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Khartoum 643 Small sailboat off shore, near junction of the Blue Nile ~1952 Sudan 9 x & White Nile. AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Khartoum 644 Man standing on docked row boat pulling in fishing net. ~1952 Sudan 10 x AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Khartoum Man tying cow to irrigation pump wheel. ~1952 x Sudan 11 AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Khartoum Man using levee to pull water from river up to cliff face. ~1952 Sudan 12 x AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Khartoum Man preparing soil in farm field, with girl walking by ~1952 Sudan 13 x casually. -

The Stable Isotope Characteristics of Precipitation in the Middle East

water Article The Stable Isotope Characteristics of Precipitation in the Middle East Highlighting the Link between the Köppen Climate Classifications and the δ18O and δ2H Values of Precipitation Mojtaba Heydarizad 1, Luis Gimeno 1,*, Rogert Sorí 1,2 , Foad Minaei 3,4 and Javad Eskandari Mayvan 5 1 Centro de Investigación Mariña, Environmental Physics Laboratory (EPhysLab), Campus As Lagoas s/n, Universidade de Vigo, 32004 Ourense, Spain; [email protected] (M.H.); [email protected] (R.S.) 2 Instituto Dom Luiz (IDL), Faculdade de Ciências, Universidade de Lisboa, 1749-016 Lisboa, Portugal 3 Department of Geography, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Mashhad 917794883, Iran; [email protected] 4 Geographic Information Science/System and Remote Sensing Laboratory (GISSRS. Lab), Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Mashhad 9177794883, Iran 5 Regional Water Company of Khorasan Razavi, Mashhad 9185916196, Iran; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The Middle East is faced with a water shortage crisis due to its semiarid and arid climate. In this paper, precipitation as an important part of the water cycle was evaluated in 43 stations across the Middle East using the stable isotope technique to study the parameters which influence the stable isotope content of precipitation. First, the stepwise regression model was applied to determine the Citation: Heydarizad, M.; main geographical and climatological factors affecting the stable isotopes in precipitation. Secondly, Gimeno, L.; Sorí, R.; Minaei, F.; the stepwise model was also used to simulate the stable isotope values in precipitation. Furthermore, Mayvan, J.E. The Stable Isotope due to the notable climatic variations across the Middle East, the precipitation sampling stations Characteristics of Precipitation in the Middle East Highlighting the Link were classified into six groups based on the Köppen climate zones. -

Egypt Vs. Algeria – the Nasty Politics of Football

Centro de Estudios y Documentación InternacionalesCentro de Barcelona opiniónCIDOB EGYPT VS. ALGERIA – THE NASTY 52 POLITICS OF FOOTBALL DECEMBER 2009 Francis Ghilès Senior Researcher, CIDOB n Thursday 12th November the bus ferrying the Algerian national football team from Cairo airport to the hotel was stoned by Egyptians – the police did not intervene before a number of players were seriously wounded, Osome even needed stitches. The Pharaohs won 2-0 against the Fennecs (desert fox) thus forcing a play- off which was to be played in the capital of Sudan, Khartoum, on 18th November. The outcome of that match would decide which team would qualify to represent Africa for the finals of the World Cup due in South Africa next year. Ugly incidents occurred between supporters of both teams after the first match which spread to three countries in the run up to the second match. Reckless reporting fanned by Egyptian and Algerian political leaders resulted in large scale demonstrations in Algiers when the Algerian popular newspaper Chourouk reported one Algerian fan had died – it later turned out he had fainted. President Mubarak’s sons joined the fray: on Egyptian television they attacked Algerians for being terrorists. Blogs meanwhile went into overdrive, Algerian bloggers promising to avenge the blood of their brother “killed” in Cairo, Egyp- tians sneering at Algerians for having been colonised by the French for 132 years. The Algerian authorities meanwhile slapped a $600m tax bill on Orascom, the Egyptian company which has a high profile in Algeria and whose headquarters were thrashed by crowds of Algerian supporters. -

International Currency Codes

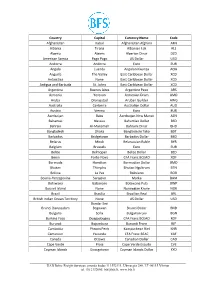

Country Capital Currency Name Code Afghanistan Kabul Afghanistan Afghani AFN Albania Tirana Albanian Lek ALL Algeria Algiers Algerian Dinar DZD American Samoa Pago Pago US Dollar USD Andorra Andorra Euro EUR Angola Luanda Angolan Kwanza AOA Anguilla The Valley East Caribbean Dollar XCD Antarctica None East Caribbean Dollar XCD Antigua and Barbuda St. Johns East Caribbean Dollar XCD Argentina Buenos Aires Argentine Peso ARS Armenia Yerevan Armenian Dram AMD Aruba Oranjestad Aruban Guilder AWG Australia Canberra Australian Dollar AUD Austria Vienna Euro EUR Azerbaijan Baku Azerbaijan New Manat AZN Bahamas Nassau Bahamian Dollar BSD Bahrain Al-Manamah Bahraini Dinar BHD Bangladesh Dhaka Bangladeshi Taka BDT Barbados Bridgetown Barbados Dollar BBD Belarus Minsk Belarussian Ruble BYR Belgium Brussels Euro EUR Belize Belmopan Belize Dollar BZD Benin Porto-Novo CFA Franc BCEAO XOF Bermuda Hamilton Bermudian Dollar BMD Bhutan Thimphu Bhutan Ngultrum BTN Bolivia La Paz Boliviano BOB Bosnia-Herzegovina Sarajevo Marka BAM Botswana Gaborone Botswana Pula BWP Bouvet Island None Norwegian Krone NOK Brazil Brasilia Brazilian Real BRL British Indian Ocean Territory None US Dollar USD Bandar Seri Brunei Darussalam Begawan Brunei Dollar BND Bulgaria Sofia Bulgarian Lev BGN Burkina Faso Ouagadougou CFA Franc BCEAO XOF Burundi Bujumbura Burundi Franc BIF Cambodia Phnom Penh Kampuchean Riel KHR Cameroon Yaounde CFA Franc BEAC XAF Canada Ottawa Canadian Dollar CAD Cape Verde Praia Cape Verde Escudo CVE Cayman Islands Georgetown Cayman Islands Dollar KYD _____________________________________________________________________________________________ -

Supplementary Material Barriers and Facilitators to Pre-Exposure

Sexual Health, 2021, 18, 130–39 © CSIRO 2021 https://doi.org/10.1071/SH20175_AC Supplementary Material Barriers and facilitators to pre-exposure prophylaxis among A frican migr ants in high income countries: a systematic review Chido MwatururaA,B,H, Michael TraegerC,D, Christopher LemohE, Mark StooveC,D, Brian PriceA, Alison CoelhoF, Masha MikolaF, Kathleen E. RyanA,D and Edwina WrightA,D,G ADepartment of Infectious Diseases, The Alfred and Central Clinical School, Monash Un iversity, Melbourne, Vic., Australia. BMelbourne Medical School, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Vic., Australia. CSchool of Public Health and Preventative Medicine, Monash University, Melbourne, Vic., Australia. DBurnet Institute, Melbourne, Vic., Australia. EMonash Infectious Diseases, Monash Health, Melbourne, Vi, Auc. stralia. FCentre for Culture, Ethnicity & Health, Melbourne, Vic., Australia. GPeter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Vic., Australia. HCorresponding author. Email: [email protected] File S1 Appendix 1: Syntax Usedr Dat fo abase Searches Appendix 2: Table of Excluded Studies ( n=58) and Reasons for Exclusion Appendix 3: Critical Appraisal of Quantitative Studies Using the ‘ Joanna Briggs Institute Checklist for Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies’ (39) Appendix 4: Critical Appraisal of Qualitative Studies U sing a modified ‘CASP Qualitative C hecklist’ (37) Appendix 5: List of Abbreviations Sexual Health © CSIRO 2021 https://doi.org/10.1071/SH20175_AC Appendix 1: Syntax Used for Database -

HARDSHIP CLASSIFICATION Consolidated List of Entitlements Circular

INTERNATIONAL CIVIL SERVICE COMMISSION HARDSHIP CLASSIFICATION Consolidated List of Entitlements Circular ICSC/CIRC/HC/25 Approved By: Mr. Larbi Djacta, Chairman Date: 16 December 2019 Additional important information from ICSC Chairman Copyright © United Nations 2017 United Nations International Civil Service Commission (HRPD) Consolidated list of entitlements - Effective 1 January 2020 Country/Area Name Duty Station Review Date Eff. Date Class Duty Station ID AFGHANISTAN Bamyan 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG002 AFGHANISTAN Faizabad 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG003 AFGHANISTAN Gardez 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG018 AFGHANISTAN Herat 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG007 AFGHANISTAN Jalalabad 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG008 AFGHANISTAN Kabul 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG001 AFGHANISTAN Kandahar 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG009 AFGHANISTAN Khowst 01/Jan/2019 01/Jan/2019 E AFG010 AFGHANISTAN Kunduz 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG020 AFGHANISTAN Maymana (Faryab) 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG017 AFGHANISTAN Mazar-I-Sharif 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG011 AFGHANISTAN Pul-i-Kumri 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG032 ALBANIA Tirana 01/Jan/2019 01/Jan/2019 A ALB001 ALGERIA Algiers 01/Jan/2018 01/Jan/2018 B ALG001 ALGERIA Tindouf 01/Jan/2018 01/Jan/2018 E ALG015 ALGERIA Tlemcen 01/Jul/2018 01/Jul/2018 C ALG037 ANGOLA Dundo 01/Jul/2018 01/Jul/2018 D ANG047 ANGOLA Luanda 01/Jul/2018 01/Jan/2018 B ANG001 ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA St. Johns 01/Jan/2019 01/Jan/2019 A ANT010 ARGENTINA Buenos Aires 01/Jan/2019 01/Jan/2019 A ARG001 ARMENIA Yerevan 01/Jan/2019 01/Jan/2019 -

*Page 1 of 15 MG Passport Number 022689 / 6399 Name: Abdallah Mohamed Dob: 25 August 1972 Pob: Moroni, Comoros Profession: P

AFGP-2002-800089 *Page 1 of 15 MG Passport Number 022689 / 6399 Name: Abdallah Mohamed DoB: 25 August 1972 PoB: Moroni, Comoros Profession: Pupil Place of Residence: Moroni, Comoros AFGP-2002-800089 *Page 2 of 15 MG Arrival cachet Moroni-Haya 11 Mar 1994 AFGP-2002-800089 Passport issued in Moroni on 25 (?) Oct 1990, and expired on 24 Oct 1995. Passport renewed in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia on 16 Oct 1995, valid until 15 Oct 2000 Seal of the Republic of Comoros AFGP-2002-800089 *Page 4 of 15 MG Passport Number 022689 Exit Visa 8253/No90/DSN/PAF Name: Fazul Abdallah Issued 16/11/90 signed by Ahamada Zaldou AFGP-2002-800089 *Page 5 of 15 MG Visa No. /90, issued 23 Nov 90 Arrival Date in Mauritius 23 Nov 1990. Departure from Mauritius 29 Nov 1990 Kenya Arrival in Mandera, 6 Feb 94 Single journey to Kenya Business Visa dated 6/2/94 AFGP-2002-800089 *Page 6 of 15 MG Pakistani Resident Visa No. 5464 Type of visa: Entry Date of issue: 20/11/1991 Valid for One Year Status: Single Expires 19/11/1992 *Page 7 of 15 MG AFGP-2002-800089 Kenya one week transit visa issued on Feb 3, 1993 Visa No. 137/2/93 Kenya High Commission in Islamabad Arrival in Islamabad on 3/2/93 Departure from Karachi, Pakistan ?/1993 IM/No C285642 *Page 8 of 15 MG AFGP-2002-800089 Visa No 86/93 Name Fazul Abdallah Mohamed Type of visa: Tourist Visa for Djibouti issued in Nairobi, Kenya 11/2/93. -

KHARTOUM, Sudan Source Year

KHARTOUM, Sudan Source Year http://citymayors.com/statistics/urban_2006_1. 2006 Population (millions) 4.63 html http://citymayors.com/statistics/largest-cities- Land Area (sq. km) 583 area-125.html GDP ($ billions) 35 PriceWaterhouse Coopers 2008 Human Development Index (country) 0.41 http://hdrstats.undp.org/en/tables/default.html 2011 Core city http://citymayors.com/statistics/largest-cities- 2011 Population (millions) 2.21 mayors-1.html http://citymayors.com/statistics/largest-cities- 2011 Mayor Abdul Rahman Alkheder mayors-1.html City administrator (or equivalent) Characteristics of the urban area Population growth (average annual %) UN Habitat, State of the World's Cities 2010-11 2010-2015 3.17 Population Density (per sq. km) 7942 + http://koeppen-geiger.vu-wien.ac.at/ Climate Classification Dry Economy GDP per capita ($) 7559 PriceWaterhouse Coopers 2008 Real GDP growth rate (% per annum) 6.3 PriceWaterhouse Coopers 2008-2025 Income Distribution (Gini Index) City unemployment rate (%) Energy Total energy consumption per capita (GJ) Total energy consumption per GDP (MJ/$) Total electrical use per capita (kWh) Population with authorized electrical service (%) Emissions and pollution estimated based on sectoral activity and national GHG Emissions per capita (tCO2e/cap) 2.9 emission factors estimated based on sectoral activity and national GHG Emissions per GDP (ktCO2e/$bn) 389.6 emission factors PM2.5 Concentration (mcg/cu.m) PM10 Concentration (mcg/cu.m) Water, sanitation and waste management Total water consumption per capita (litres/day) -

1 the European Union Emergency Trust Fund For

THE EUROPEAN UNION EMERGENCY TRUST FUND FOR STABILITY AND ADDRESSING THE ROOT CAUSES OF IRREGULAR MIGRATION AND DISPLACED PERSONS IN AFRICA Action Fiche for the implementation of the Horn of Africa Window 1. IDENTIFICATION Title/Number Regional Operational Centre in support of the Khartoum Process and AU-Horn of Africa Initiative (ROCK) Total cost Total estimated cost: EUR 5 000 000 Aid method / Direct Management – Negotiated Procedure with a Method of Consortium of EU Member States Agencies and Interpol implementation DAC-code 15130 Sector Legal and judicial development 2. RATIONALE AND CONTEXT 2.1. Summary of the action and its objectives This action responds to objective (3) of the EU Trust Fund, namely improved migration management in countries of origin and transit. The action is aligned with the Valletta Action Plan priority domain (4): prevention of and fight against irregular migration, migrant smuggling and trafficking of human beings. The geographical scope covers the African countries who are members of the Khartoum Process and members of the AU-Horn of Africa Initiative (AU HoAI)1. The main beneficiaries of this action will be law enforcement and judiciary authorities of the participating countries. Indirectly, the population of the targeted countries will benefit from more effective regional cooperation between authorities in dismantling criminal smuggling and trafficking networks. The overall objective of the action is to reduce the number of incidents of human trafficking and people smuggling through an enhanced regional capacity to better track and share information on irregular migration flows and associated criminal networks, and to develop common strategies and shared tools to fight human trafficking and people smuggling.