Protecting Consumers from Cybersquatters: Is the ACPA Standing Up? Heather E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trademarks, Metatags, and Initial Interest Confusion: a Look to the Past to Re- Conceptualize the Future

173 TRADEMARKS, METATAGS, AND INITIAL INTEREST CONFUSION: A LOOK TO THE PAST TO RE- CONCEPTUALIZE THE FUTURE CHAD J. DOELLINGER* INTRODUCTION Web sites, through domain names and metatags, have created a new set of problems for trademark owners. A prominent problem is the use of one’s trademarks in the metatags of a competitor’s web site. The initial interest confusion doctrine has been used to combat this problem.1 Initial interest confusion involves infringement based on confusion that creates initial customer interest, even though no transaction takes place.2 Several important questions have currently received little atten- tion: How should initial interest confusion be defined? How should initial interest confusion be conceptualized? How much confusion is enough to justify a remedy? Who needs to be confused, when, and for how long? How should courts determine when initial interest confusion is sufficient to support a finding of trademark infringement? These issues have been glossed over in the current debate by both courts and scholars alike. While the two seminal opinions involving the initial interest confusion doctrine, Brookfield Commun., Inc. v. West Coast Ent. Corp.3 and * B.A., B.S., University of Iowa (1998); J.D., Yale Law School (2001). Mr. Doellinger is an associate with Pattishall, McAuliffe, Newbury, Hilliard & Geraldson, 311 S. Wacker Drive, Chicago, Illinois 60606. The author would like to thank Uli Widmaier for his assistance and insights. The views and opinions in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Pattishall, McAuliffe, Newbury, Hilliard & Geraldson. 1 See J. Thomas McCarthy, McCarthy on Trademarks and Unfair Competition, vol. -

Basic Facts About Trademarks United States Patent and Trademark O Ce

Protecting Your Trademark ENHANCING YOUR RIGHTS THROUGH FEDERAL REGISTRATION Basic Facts About Trademarks United States Patent and Trademark O ce Published on February 2020 Our website resources For general information and links to Frequently trademark Asked Questions, processing timelines, the Trademark NEW [2] basics Manual of Examining Procedure (TMEP) , and FILERS the Acceptable Identification of Goods and Services Manual (ID Manual)[3]. Protecting Your Trademark Trademark Information Network (TMIN) Videos[4] Enhancing Your Rights Through Federal Registration Tools TESS Search pending and registered marks using the Trademark Electronic Search System (TESS)[5]. File applications and other documents online using the TEAS Trademark Electronic Application System (TEAS)[6]. Check the status of an application and view and TSDR download application and registration records using Trademark Status and Document Retrieval (TSDR)[7]. Transfer (assign) ownership of a mark to another ASSIGNMENTS entity or change the owner name and search the Assignments database[8]. Visit the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB)[9] TTAB online. United States Patent and Trademark Office An Agency of the United States Department of Commerce UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BASIC FACTS ABOUT TRADEMARKS CONTENTS MEET THE USPTO ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ 1 TRADEMARK, COPYRIGHT, OR PATENT �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� -

Intellectual Property Law in Cyberspace

Intellectual Property Law in Cyberspace Second Edition CHAPTER 7 UNIQUE ONLINE TRADEMARK ISSUES Howard S. Hogan Stephen W. Feingold Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher Kilpatrick, Townsend & Stockton Washington, D.C. New York, NY CHAPTER 8 DOMAIN NAME REGISTRATION, MAINTENANCE AND PROTECTION Howard S. Hogan Stephen W. Feingold Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher Kilpatrick, Townsend & Stockton Washington, D.C. New York, NY Intellectual Property Law in Cyberspace Second Edition G. Peter Albert, Jr. and American Intellectual Property Law Association CHAPTER 7 UNIQUE ONLINE TRADEMARK ISSUES CHAPTER 8 DOMAIN NAME REGISTRATION, MAINTENANCE AND PROTECTION American Intellectual Property Law Association A Arlington, VA Reprinted with permission For more information contact: bna.com/bnabooks or call 1-800-960-1220 Copyright © 2011 The Bureau of National Affairs, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Albert, G. Peter, 1964– Intellectual property law in cyberspace / G. Peter Albert, Jr. -- 2nd ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-57018-753-7 (alk. paper) 1. Industrial property--United States. 2. Computer networks--Law and legislation--United States. 3. Internet 4. Copyright and electronic data processing--United States. I. Title. KF3095.A77 2011 346.7304’8--dc23 2011040494 All rights reserved. Photocopying any portion of this publication is strictly prohibited unless express written authorization is first obtained from BNA Books, 1231 25th St., NW, Washington, DC 20037, bna.com/bnabooks. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use, or the internal or personal use of specific clients, is granted by BNA Books for libraries and other users registered with the Copyright Clearance Center (CCC) Transactional Reporting Service, provided that $1.00 per page is paid directly to CCC, 222 Rosewood Dr., Danvers, MA 01923, copyright.com, Telephone: 978-750-8400, Fax: 978-646-8600. -

Vol. 93 TMR 1035

Vol. 93 TMR 1035 RECONSIDERING INITIAL INTEREST CONFUSION ON THE INTERNET By David M. Klein and Daniel C. Glazer∗ I. INTRODUCTION Courts developed the theory of initial interest confusion (or “pre-sale confusion”) to address the unauthorized use of a trademark in a manner that captures consumer attention, even though no sale is ultimately completed as a result of any initial confusion. During the last few years, the initial interest confusion doctrine has become a tool frequently used to resolve Internet- related disputes.1 Indeed, some courts have characterized initial interest confusion on the Internet as a “distinct harm, separately actionable under the Lanham Act.”2 This article considers whether the initial interest confusion doctrine is necessary in the context of the Internet. Courts typically have found actionable initial interest confusion when Internet users, seeking a trademark owner’s website, are diverted by identical or confusingly similar domain names to websites in competition with, or critical of, the trademark owner. A careful analysis of these decisions, however, leads to the conclusion that a distinct initial interest confusion theory may be unnecessary to resolve cases involving the unauthorized use of a trademark as a domain name. In fact, traditional notions of trademark infringement law and multi-factor likelihood of confusion tests may adequately address the balancing of interests required in cases where courts must define the boundaries of trademark owners’ protection against the use of their marks in the domain names of competing websites. The Federal Trademark Dilution Act (FTDA)3 and the Anticybersquatting Consumer Protection Act (ACPA)4 provide additional protection against the unauthorized use of domain names that dilute famous marks or evidence a bad ∗ Mr. -

State of Rhode Island Trademark/Service Mark Guide

UDPATED 06/2019 Rhode Island Trademark/Service Mark Guide RHODE ISLAND DEPARTMENT OF STATE Trademark/Service Mark Guide The RI Department of State records the registration of state-level trademarks and service marks. Before you apply to register your mark with our office, be sure you can answer “yes” to the following questions: ¨ Have you completed a thorough search (including of the USPTO and other states’ trademark/service mark databases) to determine if your mark or a similar mark is already in use in Rhode Island or elsewhere? ¨ Is your mark currently being used in commerce in the State of Rhode Island? Have you sold or distributed goods or services where your mark is clearly distinguishable in connection with those goods or services? ¨ Have you ensured your mark is not: • Immoral, deceptive, or scandalous? • Disparaging or misrepresentative of a person (living or dead), institution, belief, or national symbol? • Inclusive of a flag or coat of arms of the United States of America, any state or municipality, or any foreign nation? • The name, signature, or image of any living person (unless you have written consent from that person)? • Merely descriptive of the goods or services? (e.g., “Frozen” for ice cream) • Merely geographically descriptive of the goods or services? (e.g., “Providence Club”) • A surname? Registration of a trademark or service mark does not prevent another person from registering the name as a d/b/a (doing business as) in the city or town where their business is located, nor does it prevent another person from incorporating under the same name. -

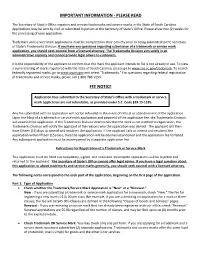

Application for Registration of a Trademark Or Service Mark

IMPORTANT INFORMATION - PLEASE READ The Secretary of State’s Office registers and renews trademarks and service marks in the State of South Carolina. Applications may be sent by mail or submitted in person at the Secretary of State’s Office. Please allow two (2) weeks for the processing of your application. Trademark and service mark applications must be completed in their entirety prior to being submitted to the Secretary of State’s Trademarks Division. If you have any questions regarding submission of a trademark or service mark application, you should seek counsel from a licensed attorney. The Trademarks Division acts solely in an administrative capacity and cannot provide legal advice to customers. It is the responsibility of the applicant to confirm that the mark the applicant intends to file is not already in use. To view a current listing of marks registered with the state of South Carolina, please go to www.sos.sc.gov/trademark. To search federally registered marks, go to www.uspto.gov and select “Trademarks.” For questions regarding federal registration of trademarks and service marks, please call 1-800-786-9199. FEE NOTICE Application fees submitted to the Secretary of State’s Office with a trademark or service mark application are not refundable, as provided under S.C. Code §39-15-1185. Any fee submitted with an application will not be refunded in the event of refusal or abandonment of the application. Upon the filing of a trademark or service mark application and payment of the application fee, the Trademarks Division will examine the application. If the Trademarks Division determines that the mark is not entitled to registration, the Trademarks Division will notify the applicant of the reasons why the application was denied. -

Trademark Basics for Nonprofits | July 2009

PUBLIC COUNSEL | COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT PROJECT | TRADEMARK BASICS FOR NONPROFITS | JULY 2009 Trademark Basics for Nonprofits Public Counsel’s Community Development Project strengthens the foundation for healthy, vibrant and economically stable neighborhoods through its comprehensive legal and capacity building support of community-based nonprofit organizations. Nonprofit organizations increasingly recognize the importance of name recognition in their fundraising endeavors, and we are often asked for legal assistance with respect to trademarks, service marks, trade names and logos. We have compiled this collection of frequently asked trademark questions and answers, and have divided them into the following categories: FAQ 1-3 Trademark Definitions FAQ 4-10 How to Establish a Trademark FAQ 11-15 Proper Use of a Trademark FAQ 16-18 Protecting a Trademark from Infringement We hope you will find this resource to be a useful preliminary guide for determining how to establish, maintain and protect these valuable corporate assets. ●●● This publication should not be construed as legal advice. These frequently asked questions and answers are provided for informational purposes only and do not constitute legal advice. While this information can help you understand the basic procedures for obtaining legal protection for your trademarks, it is very important that you obtain the advice of a qualified attorney. Public Counsel’s Community Development Project provides free legal assistance to qualifying nonprofit organizations that share our mission of serving low-income communities and addressing issues of poverty within Los Angeles County. If your organization needs legal assistance, visit www.publiccounsel.org/practice_areas/community_development or call (213) 385-2977, extension 200. 610 SOUTH ARDMORE AVENUE, LOS ANGELES, CA 90005 | TEL: 213.385.2977 | FAX: 213.385.9089 | WWW.PUBLICCOUNSEL.ORG TRADEMARK DEFINITIONS 1. -

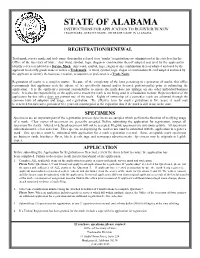

Application for Registration Or Renewal, Review the Items Below to Ensure the Application Has Been Completed

STATE OF ALABAMA INSTRUCTIONS FOR APPLICATION TO REGISTER/RENEW TRADEMARK, SERVICE MARK, OR TRADE NAME IN ALABAMA REGISTRATION/RENEWAL Trademark, service mark, and trade name (hereinafter referred to as “marks”) registrations are administered at the state level in the Office of the Secretary of State. Any word, symbol, logo, slogan or combination thereof adopted and used by the applicant to identify services rendered is a Service Mark. Any word, symbol, logo, slogan or any combination thereof adopted and used by the applicant to identify goods made or sold is a Trademark. A word, symbol, logo, slogan or combination thereof adopted and used by the applicant to identify the business, vocation, occupation, or profession is a Trade Name. Registration of marks is a complex matter. Because of the complexity of the laws pertaining to registration of marks, this office recommends that applicants seek the advice of (a) specifically trained and/or licensed professional(s) prior to submitting the application. It is the applicant’s personal responsibility to ensure the mark does not infringe on any other individual/business mark. It is also the responsibility of the applicant to ensure the mark is not being used in a fraudulent manner. Rejection/denial of the application by this office does not prevent use of the mark. Rights of ownership of a particular mark are achieved through the common laws of adoption and usage, not registration. The effective term for mark registrations is five years. A mark may be renewed for successive periods of five years six months prior to the expiration date if the mark is still in use in the state. -

Trademark Basics

Trademark basics • Signal a common source, or at least affiliation • Words, phrases, logos . • Federal / state regimes • Use in commerce • Law of marks is based on use of the brand on goods • Exclusivity derives from that type of use in commerce • Must: • “Affix” the mark to goods • Move the marked goods in commerce • Registration not needed – but Federal registration is highly beneficial • Service marks • Used “in connection with” services to signal common source • Certification / Collective marks Greg R. Vetter • www.gregvetter.org 1 Trademarks, Spring 2016 Trademarks Service Marks Certification Collective Marks Geographic Marks Indications Greg R. Vetter • www.gregvetter.org 2 Trademarks, Spring 2016 Trade‐Mark Cases 100 U.S. 82 (1879) • Act of 1870 (“An Act to revise, consolidate, and amend the statutes relating to patents and copyrights”); Act of Aug. 14, 1876 (“An act to punish the counterfeiting of trade‐mark goods, and the sale or dealing in, of counterfeit trade‐mark goods”) • U.S. Constitution, I.8.8: “[The Congress shall have Power] To promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times, to authors and inventors, the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries” The right to adopt and use a symbol or a device to distinguish the goods or property made or sold by the person whose mark it is, to the exclusion of use by all other persons, has been long recognized by the common law and the chancery courts of England and of this country and by the statutes of some of the states. It is a property right for the violation of which damages may be recovered in an action at law, and the continued violation of it will be enjoined by a court of equity, with compensation for past infringement. -

Trademark Terminal Google Ads May 2021

Trademark Terminal Keywords featuring paid Google Ads Date: November 2019-May 2021 Data source: SpyFu Article link: World Trademark Review, May 2021 Keyword term a trademark is all trademarks amazon brand registry trademark amazon seller trademark infringement amazon trademark registry american trademarks application for trademark application trade mark application trademark application trademark availability application trademarks apply for trade marks apply for trademakr apply for trademark apply for trademarks apply trademark applying for a trademark available trademark available trademarks band name trademark best trademark website brand name and trademark brand name registration brand name trademark brand register brand registration brand trademark brand trademark protection specialist brand trademark registration brand trademark search brazil trademark brazilian trademark office bureau of trademarks business name patent business name trademark business name trademarking business trademark business trademark registration business trademarks buy trademark california trademark registration can i buy a trademark domain name can you trademark a name can you trademark a phrase canada trademark canada trademark agent canada trademark registration canadian trademark office canadian trademark registration cheap trade mark cheap trade mark filing cheap trademark cheap trademarks cheap way to trademark a name cheapest way to trademark check a name for trademark check for trademark check for trademark availability check trade marks availability -

Trademarks, Cybersquatters and Domain Names

DePaul Journal of Art, Technology & Intellectual Property Law Volume 10 Issue 2 Spring 2000: American Association of Law Schools Intellectual Property Section Article 2 Meeting Trademarks, Cybersquatters and Domain Names J. Thomas McCarthy Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jatip Recommended Citation J. T. McCarthy, Trademarks, Cybersquatters and Domain Names, 10 DePaul J. Art, Tech. & Intell. Prop. L. 231 (2000) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jatip/vol10/iss2/2 This Lead Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Journal of Art, Technology & Intellectual Property Law by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. McCarthy: Trademarks, Cybersquatters and Domain Names LEAD ARTICLES TRADEMARKS, CYBERSQUATTERS AND DOMAIN NAMES J. Thomas McCarthy* I. INTRODUCTION The controversy over domain names is merely part of a larger picture in which trademark and unfair competition law will govern cyberspace. I foresee two factors driving the continued escalation of trademark disputes in cyberspace. First, cyberspace provides millions of people with a low cost way to become an instant publisher of an on-line magazine with a potential global audience. For decades it has seemed like every possible splinter religious group, offbeat political viewpoint, movie star fan club and collector's association has had a newsletter or fanzine. Now, each individual within every splinter group can have his or her own web page, putting out a message with eye-catching graphics on computer screens around the world. -

The Initial Interest Confusion Doctrine and Trademark Infringement on the Intemet, 57 Wash

Washington and Lee Law Review Volume 57 | Issue 4 Article 7 Fall 9-1-2000 The nitI ial Interest Confusion Doctrine and Trademark Infringement on the Intemet Byrce J. Maynard Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons, and the Internet Law Commons Recommended Citation Byrce J. Maynard, The Initial Interest Confusion Doctrine and Trademark Infringement on the Intemet, 57 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 1303 (2000), https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr/vol57/iss4/7 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington and Lee Law Review at Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington and Lee Law Review by an authorized editor of Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Initial Interest Confusion Doctrine and Trademark Infringement on the Intemett Bryce J. Maynard* Table of Contents I. Introduction ...................................... 1304 II. The Internet ...................................... 1306 A. The Web and Domain Names ..................... 1306 B. Search Engines and Metatags ..................... 1307 I. Trademark and Unfair Competition Law ................ 1310 A. The Dual Goals of Trademark Law ................. 1310 B. Trademark Infringement ......................... 1311 C. The Origins and Development of Initial Interest Confusion .................................... 1313 IV. Initial Interest Confusion on the Internet ................. 1318 A. M etatagging .................................. 1318 1. Brookfield Communications: The Ninth Circuit Opens the Door ......................... 1318 2. Playboy Enterprisesv. Welles: Placing Limits on Initial Interest Confusion ..................... 1320 B. Domain Names ................................ 1323 1. Pre-Brookfield: Confusion Per Se? .............. 1323 2. Post-Brookfield Three Different Directions ......