Interview with Kenneth Goldsmith | | R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

230-Newsletter.Pdf

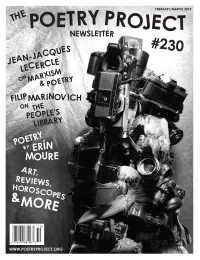

$5? The Poetry Project Newsletter Editor: Paul Foster Johnson Design: Lewis Rawlings Distribution: Small Press Distribution, 1341 Seventh Street, Berkeley, CA 94710 The Poetry Project, Ltd. Staff Artistic Director: Stacy Szymaszek Program Coordinator: Arlo Quint Program Assistant: Nicole Wallace Monday Night Coordinator: Macgregor Card Monday Night Talk Series Coordinator: Josef Kaplan Wednesday Night Coordinator: Stacy Szymaszek Friday Night Coordinator: Brett Price Sound Technician: David Vogen Videographer: Andrea Cruz Bookkeeper: Stephen Rosenthal Archivist: Will Edmiston Box Office: Courtney Frederick, Vanessa Garver, Jeffrey Grunthaner Interns/Volunteers: Nina Freeman, Julia Santoli, Alex Duringer, Jim Behrle, Christa Quint, Judah Rubin, Erica Wessmann, Susan Landers, Douglas Rothschild, Alex Abelson, Aria Boutet, Tony Lancosta, Jessie Wheeler, Ariel Bornstein Board of Directors: Gillian McCain (President), Rosemary Carroll (Treasurer), Kimberly Lyons (Secretary), Todd Colby, Mónica de la Torre, Ted Greenwald, Tim Griffin, John S. Hall, Erica Hunt, Jonathan Morrill, Elinor Nauen, Evelyn Reilly, Christopher Stackhouse, Edwin Torres Friends Committee: Brooke Alexander, Dianne Benson, Raymond Foye, Michael Friedman, Steve Hamilton, Bob Holman, Viki Hudspith, Siri Hustvedt, Yvonne Jacquette, Patricia Spears Jones, Eileen Myles, Greg Masters, Ron Padgett, Paul Slovak, Michel de Konkoly Thege, Anne Waldman, Hal Willner, John Yau Funders: The Poetry Project’s programs are made possible, in part, with public funds from The National Endowment for the Arts. The Poetry Project’s programming is made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature; and are supported, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, in partnership with the City Council. -

Kenneth Goldsmith's American Trilogy

Project MUSE - Postmodern Culture - Kenneth Goldsmith's Am... http://proxy.library.upenn.edu:2298/journals/postmodern_cultur... Postmodern Culture Volume 19, Number 1, September 2008 E-ISSN: 1053-1920 DOI: 10.1353/pmc.0.0039 Kenneth Goldsmith's American Trilogy Darren Wershler Wilfrid Laurier University Review of: Kenneth Goldsmith, The Weather. Los Angeles; Make Now, 2005, Goldsmith, Traffic. Los Angeles: Make Now, 2007, and Goldsmith, Sports. Los Angeles: Make Now, 2008. I can't help it: trilogies are nerd Kryptonite. My childhood library was chock-full of science fiction and heroic fantasy books organized into epic troikas, all of which made grandiose claims about their ability to forever change my sense of literary genre, if not of consensual reality itself. As a result, any three books that self-consciously present themselves as a trilogy have for me an aura of importance about them, one that requires further interrogation. Kenneth Goldsmith's American Trilogy-The Weather, Traffic, and Sports-is no exception. In the first half of the last century, Ezra Pound claimed in his ABC of Reading that "artists are the antennae of the race" (73). In a global digital economy, though, both wireless and networked signals come at such speed and quantity that a set of rabbit ears will no longer suffice. In 1980, Canadian poet Christopher Dewdney updated Pound's metaphor in "Parasite Maintenance," comparing contemporary artistic sensibility to the satellite dish. From such a perspective, artists are devices for the accumulation and concentration of cultural data, cool and dispassionate. The quality of the objects and texts that they produce depends in part on what "Parasite Maintenance" refers to as "the will to select" (77). -

Curated by Francesco Urbano Ragazzi May 9–November 24

Kenneth Goldsmith HILLARY: The Hillary Clinton Emails Opening Hours: Curated by Francesco Urbano Ragazzi Tuesday - Sunday, 11:00 am - 07:00 pm May 9–November 24, 2019 www.internetsaga.com Opening reception and live performance: May 9, 7:30pm [email protected] Despar Teatro Italia Campiello de l'Anconeta 1944, 30121 Venezia Despar Teatro Italia opens the door to HILLARY: The Hillary Clinton Emails, a solo exhibition by the artist and poet Kenneth Goldsmith organized by the curatorial team Francesco Urbano Ragazzi. The project will be inaugurated on 9th May 2019 in conjunction with the 58th Biennale of Visual Arts in Venice thanks to the combined commitment of The Internet Saga and Zuecca Projects, with the collaboration of Circuitozero, The Bauers, NERO and with the support of Despar Aspiag Service. The exhibition will be held in the Cinema Teatro Italia which, at the beginning of the last century, was the second and largest cinema on the island. Following a meticulous restoration of its frescoes and a careful structural renovation, the building was converted into a supermarket by Despar in 2016. In this spectacular environment with its stratified history, Kenneth Goldsmith reflects on the intermingling between the private and public spaces in the age of mass digitalization. His starting point is the case which, exactly ten years ago, changed irrevocably the notions of privacy and transparency, propaganda and democracy in Western politics. It was in 2009 when the first doubts arose regarding a private server that Hillary Clinton was using for sending e-mails during her term as Secretary of State. -

Uncreative Writing: Managing Language in the Digital Age Kenneth Goldsmith

Uncreative Writing: Managing Language in the Digital Age Kenneth Goldsmith Why Appropriation? The greatest book of uncreative writing has already been written. From 1927 to 1940, Walter Benjamin synthesized many ideas he’d been working with throughout his career into a singular work that came to be called The Arcades Project. Many have argued that it’s nothing more than hundreds of pages of notes for an unrealized work of coherent thought, merely a pile of shards and sketches. But others have claimed it to be a groundbreaking one-thousand-page work of appropriation and citation, so radical in its undigested form that it’s impossible to think of another work in the history of literature that takes such an approach. It’s a massive effort: most of what is in the book was not written by Benjamin, rather he simply copied texts written by others from stack of library books, with some passages spanning several pages. Yet conventions remain: each entry is properly cited, and Benjamin’s own “voice” inserts itself with brilliant gloss and commentary on what’s being copied. With all of the twentieth century’s twisting and pulverizing of language and the hundreds of new forms proposed for fiction and poetry, it never occurred to anybody to grab somebody else’s words and present them as their own. Borges proposed it in the form of Pierre Menard, but even Menard didn’t copy—he just happened to write the same book that Cervantes did without any prior knowledge of it. It was sheer coincidence, a fantastic stroke of genius combined with a tragically bad sense of timing. -

The Father of a Star High-School Athlete Confronts New York City's

For Immediate Release: September 28, 2015 Press Contacts: Natalie Raabe, (212) 286-6591 Molly Erman, (212) 286-7936 Adrea Piazza, (212) 286-4255 The Father of a Star High-School Athlete Confronts New York City’s Patterns of Violence In the October 5, 2015, issue of The New Yorker, in “A Daughter’s Death” (p. 52), Jennifer Gonnerman investigates the violence occur- ring in New York City’s public-housing projects, and examines one father’s efforts to bring peace to his Harlem neighborhood in the aftermath of his teen-age daughter’s murder. “Last year, there were three hundred and thirty-three homicides in New York City, the lowest number of any year on record,” Gonnerman writes. “But almost twenty per cent of the shootings in the city occur in public-housing developments, which hold less than five per cent of the population.” Violent crime is so concentrated in some projects that to residents it can feel as if shootings and side- walk memorials were part of everyday life. For decades, the General Ulysses S. Grant Houses and Manhattanville Houses in Harlem have been embroiled in a feud, perpetuated by young residents who belong to “crews.” As Gonnerman explains, the crews are not affiliated with estab- lished gangs, and their disputes were not about drugs or money. “Rather, they fought over turf and status,” she writes. Taylonn Murphy’s eigh- teen-year-old daughter Tayshana—widely known by her nickname, Chicken—was a star athlete on the verge of applying to college when she was killed inside the Grant Houses, where she lived, on September 11, 2011. -

Kenneth Goldsmith's

What Really Happened? Kenneth Goldsmith’s “7+ Deaths and Disasters,” Sophie Calle’s, Take Care of Yourself Marjorie Perloff “Je voulais dire ça littéralement et dans tous les sens. ” Arthur Rimbaud, Une Saison en enfer Abstract In Seven American Deaths and Disasters (2013), Kenneth Goldsmith recounted a set of tragic and unanticipated events in recent American history by using transcriptions of radio and TV broadcasts, usually from minor networks. Designed to be an “eighth American disaster,” Goldsmith presented The Body of Michael Brown, a performance based on the St. Louis autopsy report at the “Interrupt 3” conference at Brown University (13 March 2015), eliciting widespread criticism and controversy. Seemingly very different from Goldsmith—Sophie Calle’s projects, for the past few decades, set up particular procedural processes that raise pressing epistemological questions, especially about the nature of relationships, personal and political. One of her recent projects, Prenez soin de vous (Take Care of Yourself) that was based on her installation for the Venice Biennale in 2007, comprises comments by 107 women on an email that Calle received from her then lover. In this project, Calle uses the “real” words of others to create a montage of possible interpretations of the discourse that confronts us in our daily lives. For Calle, as for Goldsmith, the most troubling gap is that between information and knowledge, while the issue, that a conceptual poetics can take as a premise, is that the body most difficult to get inside of turns -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Reading from a to Z

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Reading from A to Z: The Alphabetic Sequence in Experimental Literature and Visual Art A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in English by Jacquelyn Wendy Ardam 2015 © Copyright by Jacquelyn Wendy Ardam 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Reading from A to Z: The Alphabetic Sequence in Experimental Literature and Visual Art by Jacquelyn Wendy Ardam Doctor of Philosophy in English University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor Michael A. North, Chair “Reading from A to Z” argues for the significance of the alphabetic sequence to the transatlantic experimental literature and visual art from the modern period to the present. While it may be most familiar to us as a didactic device to instruct children, various experimental writers and avant-gardists have used the alphabetic sequence to structure some of their most radical work. The alphabetic sequence is a culturally-meaningful trope with great symbolic import; we are, after all, initiated into written discourse by learning our ABCs, and the sequence signifies logic, sense, and an encyclopedic and linear way of thinking about and representing the world. But the string of twenty-six arbitrary signifiers also represents rationality’s complete opposite; the alphabet is just as potent a symbol and technology of nonsense, arbitrariness, and (children’s) play. These inherent tensions between meaning and arbitrariness, sense and nonsense, order and chaos have been exploited by a century of ii experimental writers and artists who have employed the alphabetic sequence as a device for formal experimentation, radical content, and institutional and cultural critique. -

Detainees: Re: Penn's Kenneth Goldsmith to Perform at the White

Detainees: Re: Penn's Kenneth Goldsmith to perform at the Whi... http://wwwwsonneteighteencom.blogspot.com/2011/05/re-penn... Share Report Abuse Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In Detainees Thursday, May 5, 2011 Re: Penn's Kenneth Goldsmith to perform at the White House next week Hi Al, To be a minstrel for a mass murderer is nothing to be proud of, Al. This just heightens my contempt for the state of American poetry. Did Bertolt Brecht dance for Hitler? Future generations will look back at us and retch. Very sad. Linh --- On Thu, 5/5/11, Al Filreis wrote: From: Al Filreis Subject: Penn's Kenneth Goldsmith to perform at the White House next week To: "Al Filreis" Date: Thursday, May 5, 2011, 9:06 AM Dear friends: Below is a statement just now released from the White House. Kenneth Goldsmith, who teaches in the Center for Programs in Contemporary Writing (CPCW) here at Penn and is a close affiliate of the Kelly Writers House, will be among the poets performing at the May 11 event. And with Mrs. Obama, he will 1 of 21 10/26/11 3:31 PM Detainees: Re: Penn's Kenneth Goldsmith to perform at the Whi... http://wwwwsonneteighteencom.blogspot.com/2011/05/re-penn... lead a poetry workshop for children. Kenny has been teaching a Creative Writing workshop called "Uncreative Writing" for a number of years at Penn. And every other year (continuing in 2011-12), he teaches an innovative year-long contemporary art/writing seminar that is a collaboration of CPCW and the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA). -

Printf("Hello, World\N"); }

Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Almenn bókmenntafræði main() { printf("hello, world\n"); } An Essay on Kenneth Goldsmith Ritgerð til B.A.-prófs í almennri bókmenntafræði Mirjam Maeekalle Kt.: 090593-3829 Leiðbeinandi: Benedikt Hjartarson Maí 2018 Abstract The foundation to literary studies, are the conflicts and discussions around it, for without the cultural developments, literature would be stuck in a rut. Seeing how we are in the middle of vast developing technological advancement, this essay will be an attempt to explore the effects it has on literature, as well as how literature reacts to these developments. This will be done through an analysis of the works of Kenneth Goldsmith, specifically his books Day and Fidget, which go against the traditional values of a literary work and are the preliminary works to the two chapters the essay is divided into. The essay begins with an overview on Goldsmith’s poetics, with a little bit of controversy and context, along with a short introduction to the main sidekick to Goldsmith’s works, Walter Benjamin. The first half of the second chapter of the thesis focuses mainly on Benjamin’s essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction“ and the course of art from the beginning of the 20th century along with Alexander Alberro’s essay “Reconsidering Conceptual Art, 1966-1977”. The main speculations evolve around the invention of photography, in pursuit to connect the modifications it had on art to the alterations literature is forced through in the era of the internet. Whereas in the second half, the book Fidget will be shortly analysed based on the notion of materialized language. -

ARIANA REINES 213 300 2779 / [email protected] / / 435 W 22 Street / New York, NY 11385

ARIANA REINES 213 300 2779 / [email protected] http://arianareines.tumblr.com / http://lazyeyehaver.com / 435 W 22 Street / New York, NY 11385 EDUCATION - matriculating toward the M.Div, Harvard Divinity School, Fall 2019 - MA, ABD in Media & Communication, European Graduate School, 2006. - Fully-funded graduate study in the Department of French and Romance Philology, Columbia University, 2004-2006. Advisor: Sylvère Lotringer - BA in English (Writing Concentration) & French (Translation Concentration), Summa Cum Laude & Phi Beta Kappa, Barnard College, 2003. BOOKS - A SAND BOOK, Tin House Books, June 2019. - THE ORIGIN OF THE WORLD: ESSAYS, Semiotext(e), forthcoming 2020. - TELEPHONE, Wonder, May 2018. Norwegian Translation 2017. - MERCURY, FenceBooks, December 2011. Norwegian Translation 2017. - COEUR DE LION, Mal-O-Mar Editions. November 2007; FenceBooks, November 2011. Norwegian, Swedish, & Spanish (Argentina) Translations 2015-2017. - THE COW, Alberta Prize, FenceBooks. December, 2006. chapbooks - TIFFANY’S POEMS & RAMAYANA, 2 chapbooks, The Song Cave, Fall 2015. - THE ORIGIN OF THE WORLD, commissioned by Semiotext(e) for the Whitney Biennial, March 2014. - BEYOND RELIEF, chapbook with Celina Su, Belladonna* chaplet series, 2013. - THURSDAY, chapbook, Spork, February 2012. MAJOR TRANSLATIONS - PRELIMINARY NOTES TOWARD A THEORY OF THE YOUNG-GIRL by TIQQUN, Semiotext(e), Interventions Series, Fall 2012. - THE LITTLE BLACK BOOK OF GRISELIDIS REAL: DAYS AND NIGHTS OF AN ANARCHIST WHORE by Jean-Luc Hennig, Semiotext(e), Fall 2009. - MY HEART LAID BARE by Charles Baudelaire, Mal-O-Mar Editions, October 2009. ANTHOLOGIES -KINK, Garth Greenwell & Reese Kwon, Eds., Simon & Schuster, 2020. -SPELLS: 21st Century Occult Poetry, Sarah Shin, Ed. Ignota Books, London, 2018. -READINGS IN CONTEMPORARY POETRY: AN ANTHOLOGY, Dia Foundation, April 2017. -

Against Expression an Anthology of Conceptual Writing

Against Expression Against Expression An Anthology of Conceptual Writing E D I T E D B Y C R A I G D W O R K I N A N D KENNETH GOLDSMITH Northwestern University Press Evanston Illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © by Northwestern University Press. Published . All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America + e editors and the publisher have made every reasonable eff ort to contact the copyright holders to obtain permission to use the material reprinted in this book. Acknowledgments are printed starting on page . Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Against expression : an anthology of conceptual writing / edited by Craig Dworkin and Kenneth Goldsmith. p. cm. — (Avant- garde and modernism collection) Includes bibliographical references. ---- (pbk. : alk. paper) . Literature, Experimental. Literature, Modern—th century. Literature, Modern—st century. Experimental poetry. Conceptual art. I. Dworkin, Craig Douglas. II. Goldsmith, Kenneth. .A .—dc o + e paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, .-. To Marjorie Perlo! Contents Why Conceptual Writing? Why Now? xvii Kenneth Goldsmith + e Fate of Echo, xxiii Craig Dworkin Monica Aasprong, from Soldatmarkedet Walter Abish, from Skin Deep Vito Acconci, from Contacts/ Contexts (Frame of Reference): Ten Pages of Reading Roget’s ! esaurus from Removal, Move (Line of Evidence): + e Grid Locations of Streets, Alphabetized, Hagstrom’s Maps of the Five Boroughs: . Manhattan Kathy Acker, from Great Expectations Sally Alatalo, from Unforeseen Alliances Paal Bjelke Andersen, from + e Grefsen Address Anonymous, Eroticism David Antin, A List of the Delusions of the Insane: What + ey Are Afraid Of from Novel Poem from + e Separation Meditations Louis Aragon, Suicide Nathan Austin, from Survey Says! J. -

Against Expression: an Anthology of Conceptual Writing

Against Expression Against Expression An Anthology of Conceptual Writing E D I T E D B Y C R A I G D W O R K I N A N D KENNETH GOLDSMITH Northwestern University Press Evanston Illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © by Northwestern University Press. Published . All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America + e editors and the publisher have made every reasonable eff ort to contact the copyright holders to obtain permission to use the material reprinted in this book. Acknowledgments are printed starting on page . Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Against expression : an anthology of conceptual writing / edited by Craig Dworkin and Kenneth Goldsmith. p. cm. — (Avant- garde and modernism collection) Includes bibliographical references. ---- (pbk. : alk. paper) . Literature, Experimental. Literature, Modern—th century. Literature, Modern—st century. Experimental poetry. Conceptual art. I. Dworkin, Craig Douglas. II. Goldsmith, Kenneth. .A .—dc o + e paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, .-. To Marjorie Perlo! Contents Why Conceptual Writing? Why Now? xvii Kenneth Goldsmith + e Fate of Echo, xxiii Craig Dworkin Monica Aasprong, from Soldatmarkedet Walter Abish, from Skin Deep Vito Acconci, from Contacts/ Contexts (Frame of Reference): Ten Pages of Reading Roget’s ! esaurus from Removal, Move (Line of Evidence): + e Grid Locations of Streets, Alphabetized, Hagstrom’s Maps of the Five Boroughs: . Manhattan Kathy Acker, from Great Expectations Sally Alatalo, from Unforeseen Alliances Paal Bjelke Andersen, from + e Grefsen Address Anonymous, Eroticism David Antin, A List of the Delusions of the Insane: What + ey Are Afraid Of from Novel Poem from + e Separation Meditations Louis Aragon, Suicide Nathan Austin, from Survey Says! J.