Sovereign Defaults in Court Henrik Enderlein

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sovereign Defaults and Debt Restructurings: Historical Overview

Sovereign Defaults and Debt Restructurings: 1 Historical Overview Debt crises and defaults by sovereigns—city-states, kingdoms, and empires—are as old as sovereign borrowing itself. The first recorded default goes back at least to the fourth century B.C., when ten out of thirteen Greek municipalities in the Attic Maritime Association de- faulted on loans from the Delos Temple (Winkler 1933). Most fiscal crises of European antiquity, however, seem to have been resolved through ‘‘currency debasement’’—namely, inflations or devaluations— rather than debt restructurings. Defaults cum debt restructurings picked up in the modern era, beginning with defaults in France, Spain, and Portugal in the mid-sixteenth centuries. Other European states fol- lowed in the seventeenth century, including Prussia in 1683, though France and Spain remained the leading defaulters, with a total of eight defaults and six defaults, respectively, between the sixteenth and the end of the eighteenth centuries (Reinhart, Rogoff, and Savastano 2003). Only in the nineteenth century, however, did debt crises, defaults, and debt restructurings—defined as changes in the originally envis- aged debt service payments, either after a default or under the threat of default—explode in terms of both numbers and geographical inci- dence. This was the by-product of increasing cross-border debt flows, newly independent governments, and the development of modern fi- nancial markets. In what follows, we begin with an overview of the main default and debt restructuring episodes of the last two hundred years.1 We next turn to the history of how debt crises were resolved. We end with a brief review of the creditor experience with sovereign debt since the 1850s. -

Department of Administrative Services Offset Programs

ISSUE REVIEW Fiscal Services Division January 5, 2017 Department of Administrative Services Income Offset Program ISSUE This Issue Review examines the Income Offset Program administered by the Department of Administrative Services (DAS). Money owed to the state and local governments is offset or withheld from individuals and vendors to recover delinquent payments. AFFECTED AGENCIES Departments of Administrative Services, Revenue, Human Services, and Inspections and Appeals, the Judicial Branch, Iowa Workforce Development, the Regents Institutions, community colleges, and local governments CODE AUTHORITY Iowa Code sections 8A.504, 99D.28, 99F.19, and 99G.38 Iowa Administrative Code 11.40 BACKGROUND The Income Offset Program began in the 1970s under the Department of Revenue (DOR).1 During that time, state income tax refunds were withheld by the Department for liabilities owed to the Department and other state agencies. In 1989, the Program expanded to include payments issued to vendors.2 In 2003, the Finance portion of the Department of Revenue and Finance became the State Accounting Enterprise (SAE) of the DAS and the new home of the Income Offset Program. Iowa Code section 8A.504 permits the DAS-SAE to recover delinquent payments owed to state and political subdivisions by withholding payments that would otherwise be paid to individuals and vendors.3 The DAS-SAE applies the money toward the debt an individual or vendor owes 4 to the state of Iowa or local governments. For example, if an individual or vendor qualifies for a 1 The Department of Revenue became the Department of Revenue and Finance in 1986 as a result of government reorganization and returned back to the Department of Revenue when the Department of Administrative Services (DAS) was created in 2003. -

Judgment Claims in Receivership Proceedings*

JUDGMENT CLAIMS IN RECEIVERSHIP PROCEEDINGS* JOHN K. BEACH Connecticuf Supreme Court of Errors In view of the importance of the subject it is unfortunate that so few of the reported cases on equitable receiverships of corporations have dealt in any comprehensive way with the principles underlying the administrating of the fund for the benefit of creditors. The result is that controversy has outstripped authoritative decision, and the subject is unsettled. To this generalization an exception must be noted in respect of the special topic of the application of current rail- way income to current expenses, before the payment of mortgage 1 indebtedness. On another disputed topic, the provability of imma.ure claims, the law, or at least the right principle of decision, has been settled, by the notable opinion of Judge Noyes in Pennsylvania Steel Company v. New York City Railway Company,2 followed and rein- forced by that of Mr. Justice Holmes in William Filene'sSons Company v. Weed.' Notwithstanding these important exceptions, the dearth of authority on the general subject is such that Judge Noyes refers to a case cited in his opinion as "almost the only case in which rules have "been formulated with respect to the provability of claims against "insolvent corporations."4 Upon the particular phase of the subject here discussed, the decisions are to some extent in conflict, and no attempt seems to have been made in text books or decisions to examine the question in the light of principle. Black, for example, dismisses the subject by saying it. is generally conceded that a receiver and the corporation whose property is under his charge "are so far in privity that a judgment against the * This paper deals only with judgments against the defendant in the receiver- ship, regarded as evidence of the validity and amount of the judgment creditor's claims for dividends to be paid out of the fund in the receiver's hands. -

Self-Represented Creditor

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT DISTRICT OF MASSACHUSETTS A GUIDE FOR THE SELF-REPRESENTED CREDITOR IN A BANKRUPTCY CASE June 2014 Table of Contents Subject Page Number Legal Authority, Statutes and Rules ....................................................................................... 1 Who is a Creditor? .......................................................................................................................... 1 Overview of the Bankruptcy Process from the Creditor’s Perspective ................... 2 A Creditor’s Objections When a Person Files a Bankruptcy Petition ....................... 3 Limited Stay/No Stay ..................................................................................................... 3 Relief from Stay ................................................................................................................ 4 Violations of the Stay ...................................................................................................... 4 Discharge ............................................................................................................................. 4 Working with Professionals ....................................................................................................... 4 Attorneys ............................................................................................................................. 4 Pro se ................................................................................................................................................. -

FERC Vs. Bankruptcy Courts—The Battle Over Jurisdiction Continues

FERC vs. Bankruptcy Courts—The Battle over Jurisdiction Continues By Hugh M. McDonald and Neil H. Butterklee* In energy industry bankruptcies, the issue of whether a U.S. bankruptcy court has sole and exclusive jurisdiction to determine a debtor’s motion to reject an executory contract has mostly involved a jurisdictional struggle involving the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. The dearth of judicial (and legislative) guidance on this issue has led to shifting decisions and inconsistent outcomes leaving counterparties to contracts in still uncertain positions when a contract counterparty commences a bankruptcy case. The authors of this article discuss the jurisdiction conundrum. The COVID-19 pandemic has put pressure on all aspects of the United States economy, including the energy sector. Counterparties to energy-related contracts, such as power purchase agreements (“PPAs”) and transportation services agreements (“TSAs”), may need to commence bankruptcy cases to restructure their balance sheets and, as part of such restructuring, may seek to shed unprofitable or out-of-market contracts. However, this situation has created a new stage for the decades-old jurisdictional battle between bankruptcy courts and energy regulators. The U.S. Bankruptcy Code allows a debtor to assume or reject executory contracts with the approval of the bankruptcy judge presiding over the case.1 The standard employed by courts when assessing the debtor’s request to assume or reject is the business judgment standard. A debtor merely has to demonstrate that assumption or rejection is in the best interest of the estate and the debtor’s business. However, most energy-related contracts are subject to regulatory oversight by federal and/or state regulatory bodies, which, depending on the type of contract that is being terminated, apply different standards—most of which take into account public policy concerns. -

II. the Onset of Insolvency Or Financial Distress

Reproduced with permission from Corporate Practice Series, "Corporate Governance of Insolvent and Troubled Entities," Portfolio 109 (109 CPS II). Copyright 2017 by The Bureau of National Affairs, Inc. (800-372-1033) http://www.bna.com II. The Onset of Insolvency or Financial Distress A. Introduction Because a Chapter 11 reorganization can be expensive and time consuming, a troubled corporation may seek to right itself through an out-of-court transaction—such as a recapitalization, merger or asset sale. These transactions and the directors' decisions concerning them are analyzed under state corporation law. Corporation law also provides a state law alternative to a Chapter 7 liquidation through procedures for voluntary and forced dissolution as well as ancillary remedies such as the appointment of a receiver to marshal a corporation's assets, sell those assets, distribute the proceeds to creditors, and take other steps to wind down a corporation. That said, as discussed below, state law insolvency proceedings have limitations that often make them an unsuitable alternative to federal bankruptcy proceedings. B. Director Duties in the `Zone of Insolvency' and Insolvency As discussed in Chapter I, § 141(a) of the DGCL gives directors the authority and power to manage a corporation, and in exercising that authority directors are subject to the fiduciary duties of care and loyalty. Under ordinary circumstances, these fiduciary duties require that directors maximize the value of the corporation for the benefit of its stockholders, who are the beneficiaries of any increase in the value of the corporation. When a corporation is insolvent, however, the value of the corporation's equity may be zero. -

How to Handle Bad Debts There Often Comes a Time When Businesses

How to Handle Bad Debts There often comes a time when businesses must account for nonpaying customers. This typically means deleting them from the company’s books and from regular accounts receivable records by writing off the outstanding receivable as a bad debt. Because bad debt write offs impact a firm’s cash flow and profit margins, credit professionals must use a combination of allowances and write-off guidelines, which must conform with Internal Revenue Service regulations, to handle this process. A firm’s general credit policy should include this information. Some companies establish allowance for bad debt accounts, contra asset accounts, to recognize that write offs are inevitable and to provide management with estimates of potential write offs. In 1986, the IRS repealed the use of the allowance method for tax purposes, taking the position that specific accounts are to be charged off only after they have been identified as uncollectible. Accountants, however, continue to prefer the allowance method, also known as the income statement method, since this method allows for matching bad debt expenses more closely with the time periods in which they were created. General accepted accounting principles rules require the allowance method to be used for external reporting. Allowances for Bad Debts Allowances for bad debts or uncollectible accounts accrue for bad-debt write offs in the accounting period that revenues are recorded, thereby matching revenues and expenses. They are contra-assets, reducing current assets (accounts receivable) accordingly on the company’s balance sheet. There, offsets give a more accurate picture of the outstanding receivables and provide a clearer picture of the firm’s performance. -

UK (England and Wales)

Restructuring and Insolvency 2006/07 Country Q&A UK (England and Wales) UK (England and Wales) Lyndon Norley, Partha Kar and Graham Lane, Kirkland and Ellis International LLP www.practicallaw.com/2-202-0910 SECURITY AND PRIORITIES ■ Floating charge. A floating charge can be taken over a variety of assets (both existing and future), which fluctuate from 1. What are the most common forms of security taken in rela- day to day. It is usually taken over a debtor's whole business tion to immovable and movable property? Are any specific and undertaking. formalities required for the creation of security by compa- nies? Unlike a fixed charge, a floating charge does not attach to a particular asset, but rather "floats" above one or more assets. During this time, the debtor is free to sell or dispose of the Immovable property assets without the creditor's consent. However, if a default specified in the charge document occurs, the floating charge The most common types of security for immovable property are: will "crystallise" into a fixed charge, which attaches to and encumbers specific assets. ■ Mortgage. A legal mortgage is the main form of security interest over real property. It historically involved legal title If a floating charge over all or substantially all of a com- to a debtor's property being transferred to the creditor as pany's assets has been created before 15 September 2003, security for a claim. The debtor retained possession of the it can be enforced by appointing an administrative receiver. property, but only recovered legal ownership when it repaid On default, the administrative receiver takes control of the the secured debt in full. -

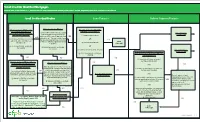

QM Small Creditor Flow Chart

SSmmaallll CCrreeddiittoorr QQuuaalliiffiieedd MMoorrttggaaggeess RReefflleeccttss rruulleess iinn eeffffeecctt oonn MMaarrcchh 11,, 22002211 bbuutt ddooeess nnoott rreefflleecctt aammeennddmmeennttss mmaaddee bbyy tthhee EEccoonnoommiicc GGrroowwtthh,, RReegguullaattoorryy RReelliieeff,, aanndd CCoonnssuummeerr PPrrootteeccttiioonn AAcctt.. Type of Compliance Presumption: SmSmaallll CCrreeddiitotorr QQuuaalliifificcaatitioonn Loan Features Balloon Payment Features Underwriting Points and Fees Portfolio Higher-Priced Loan Did you do ALL of the following?: Did you and your affiliates: Did you and your affiliates who Does the loan have ANY of the Rebuttable Presumption At the time of consummation: are creditors that extended following characteristics?: (1) Consider and verify the consumer’s YES Applies Extend 2,000 or fewer first-lien, closed- Does the loan amount fall within the following covered transactions during the Potential Small debt obligations and income or assets? STOP end residential mortgages that are points-and-fees limits? Was the loan subject to forward last calendar year have: (1) negative amortization; Creditor QM [via § 1026.43(c)(7), (e)(2)(v)]; = Non-Small Creditor QM (QM is presumed to comply subject to ATR requirements in the last YES commitment? AND YES YES = Non-Balloon-Payment QM with ATR requirements if calendar year? You can exclude loans Points-and-fees caps (adjusted annually) Assets below $2 billion (as annually OR AND it’s a higher-priced loan, but YES [§ 1026.43(e)(5)(i)(C), (f)(1)(v)] that you originated and kept in portfolio consumers can rebut the adjusted) at the end of the last STOP If Loan Amount ≥ $100,000, then = 3% of total or that your affiliate originated and kept (2) interest-only features; (2) Calculate the consumer’s monthly presumption by showing calendar year? = Non-QM If $100,000 > Loan Amount ≥ $60,000, then = $3,000 in portfolio. -

Individual Voluntary Arrangement Factsheet What Is an Individual Voluntary Arrangement (IVA)? an IVA Is a Legally Binding

Individual Voluntary Arrangement Factsheet What is an An IVA is a legally binding arrangement supervised by a Licensed Unlike debt management products, an IVA is legally binding and Individual Insolvency Practitioner, the purpose of which is to enable an precludes all creditors from taking any enforcement action against Voluntary individual, sole trader or partner (the debtor) to reach a compromise the debtor post-agreement, assuming the debtor complies with the Arrangement with his creditors and avoid the consequences of bankruptcy. The his obligations in the IVA. (IVA)? compromise should offer a larger repayment towards the creditor’s debt than could otherwise be expected were the debtor to be made bankrupt. This is often facilitated by the debtor making contributions to the arrangement from his income over a designated period or from a third party contribution or other source that would not ordinarily be available to a trustee in bankruptcy. Who can An IVA is available to all individuals, sole traders and partners who It is also often used by sole traders and partners who have suffered benefit from are experiencing creditor pressure and it is used particularly by those problems with their business but wish to secure its survival as they it? who own their own property and wish to avoid the possibility of losing believe it will be profitable in the future. It enables them to make a it in the event they were made bankrupt. greater repayment to creditors than could otherwise be expected were they made bankrupt and the business consequently were to cease trading. The procedure In theory, it is envisaged that the debtor drafts proposals for In certain circumstances, when it is considered that the debtor in brief presentation to his creditors prior to instructing a nominee, (who requires protection from creditors taking enforcement action whilst must be a Licensed Insolvency Practitioner), to review them before the IVA proposal is being considered, the nominee can file the submission to creditors (or Court if seeking an Interim Order). -

Corporate Debt Management Strategy

CORPORATE DEBT MANAGEMENT STRATEGY 1. Purpose of Strategy Stoke on Trent City Council is required to collect monies from both residents and businesses for the provision of a variety of goods and services. The council recognises that prompt income collection is vital for ensuring the authority has the resources it needs to deliver its services. The council therefore has a responsibility to ensure that appropriate mechanisms are applied to enable the collection of debt that is legally due. The council aims to achieve a high and prompt income collection rate. It endeavours to keep outstanding debt at the lowest possible level by instigating a payment culture which minimises bad debts and prevents the accumulation of debt over a period of time. 2. Scope of Strategy This Strategy covers all debts owed to the council including: Council Tax National Non Domestic Rates (NNDR, also known as Business Rates) Council House Rent Sundry Debt (general day to day business income including housing benefits overpayments and former tenant arrears). Whilst different recovery mechanisms may be used for different debt types all debt is recovered using the objectives below. 3. Objectives of Strategy The objectives of the Strategy are to: Maximise income and collection performance for the council Be firm but fair in applying this Strategy and take the earliest possible decisive and appropriate action Be courteous, helpful, open and honest at all times in all our dealings with customers Accommodate any special needs that our customers may have Work with -

Vulture Hedge Funds Attack California

JUNE 2019 HEDGE PAPERS No. 67 VULTURE HEDGE FUNDS ATTACK CALIFORNIA "Quick profits for Wall Street" versus safe, sustainable, affordable energy PG&E was plunged into bankruptcy after decades of irresponsible corporate practices led to massive wildfires and billions in new liabilities. Some of the most notorious hedge fund vultures are using their role as investors to make sure PG&E’s bankruptcy leads to big profits for their firms—at the expense of ratepayers, public safety and the environment. CONTENTS 4 | Vulture Hedge Funds Attack 10 | Meet the Billionaires and Vultures Preying on PG&E – Andrew Feldstein – Joshua S Friedman – Paul Singer – Dan Loeb – Jay Wintrob – Seth Klarman – Richard Barrera 17 | How Californias Will Get Hurt – Impact on Public Safety – Impact on Ratepayers – box: Lessons from Puerto Rico 20 | Sustainability / Climate 22 | Protect Californias —And All Americans—From Predatory Hedge Funds 24 | Hedge Funds Should Be Illegal – table: Hedge Funds That Own One Million or More Shares of PG&E 28 | About Hedge Clippers 29 | Press + General Inquiry Contacts MEET HEDGE FUNDS PUTTING THEIR 1 BILLIONS TO WORK IN HARMFUL WAYS Over three dozen hedge funds are attacking California’s biggest utility. SEVEN BILLIONAIRES AND VULTURES are leading the charge. They're treating control of PG&E as up for grabs while climate crisis wildfires rage and customers pay through the nose. The Answer: Outlaw hedge funds. Andrew Feldstein CEO, BlueMountain Capital 2 3 4 Paul Singer Dan Loeb Jay Wintrob Elliott Management Third PointCapital Oaktree