Keewatin Career Development Corporation in Discourse Surrounding the Knowledge-Based Economy and Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

June 25, 1987 Hansard

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF SASKATCHEWAN June 25, 1987 The Assembly met at 2 p.m. division of the Regina Public School, Glenda Simms. Prayers Hon. Members: — Hear, hear! ROUTINE PROCEEDINGS Mr. Goulet: — And of course my sister and brother-in-law, Allan and Monica Couture. INTRODUCTION OF GUESTS Hon. Members: — Hear, hear! Mr. Shillington: — Thank you very much, Mr. Speaker. I would like to introduce to members of the Assembly six Mr. Goulet: — And last, but not least, I’d like to welcome the students from the Regina Plains Community College, with their Montreal Lake students and their teacher, Brenda Mitchell and teacher, Ruth Quiring. driver John Hamilton. These students are here to learn about the process of our legislative procedures and here also to visit I look forward to meeting with them immediately after question Regina. They are aged 10 and 12, and so I would like to ask all period. I hope you find it informative and interesting. I invite all members to give special welcome to all the people that I have members to join me in welcoming them. mentioned, especially to this group that I have just mentioned at the end. Hon. Members: — Hear, hear! Hon. Members: — Hear, hear! Mr. Koskie: — Thank you, Mr. Speaker. It gives me a great deal of pleasure to introduce to the House, and to the members Mr. Hagel: — Mr. Speaker, I’d like to introduce to you, and here, a person I am sure that many of the members on the through you to the members of the Assembly, four people who opposition learned to respect during the past four or five years. -

Spring Runoff Highway Map.Pdf

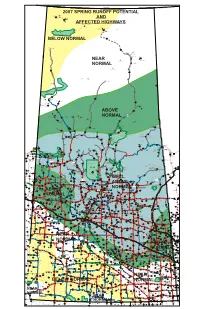

NUNAVUT TERRITORY MANITOBA NORTHWEST TERRITORIES 2007 SPRING RUNOFF POTENTIAL Waterloo Lake (Northernmost Settlement) Camsell Portage .3 999 White Lake Dam AND Uranium City 11 10 962 19 AFFECTEDIR 229 Fond du Lac HIGHWAYS Fond-du-Lac IR 227 Fond du Lac IR 225 IR 228 Fond du Lac Black Lake IR 224 IR 233 Fond du Lac Black Lake Stony Rapids IR 226 Stony Lake Black Lake 905 IR 232 17 IR 231 Fond du Lac Black Lake Fond du Lac ATHABASCA SAND DUNES PROVINCIAL WILDERNESS PARK BELOW NORMAL 905 Cluff Lake Mine 905 Midwest Mine Eagle Point Mine Points North Landing McClean Lake Mine 33 Rabbit Lake Mine IR 220 Hatchet Lake 7 995 3 3 NEAR Wollaston Lake Cigar Lake Mine 52 NORMAL Wollaston Lake Landing 160 McArthur River Mine 955 905 S e m 38 c h u k IR 192G English River Cree Lake Key Lake Mine Descharme Lake 2 Kinoosao T 74 994 r a i l CLEARWATER RIVER PROVINCIAL PARK 85 955 75 IR 222 La Loche 914 La Loche West La Loche Turnor Lake IR 193B 905 10 Birch Narrows 5 Black Point 6 IR 221 33 909 La Loche Southend IR 200 Peter 221 Ballantyne Cree Garson Lake 49 956 4 30 Bear Creek 22 Whitesand Dam IR 193A 102 155 Birch Narrows Brabant Lake IR 223 La Loche ABOVE 60 Landing Michel 20 CANAM IR 192D HIGHWAY Dillon IR 192C IR 194 English River Dipper Lake 110 IR 193 Buffalo English River McLennan Lake 6 Birch Narrows Patuanak NORMAL River Dene Buffalo Narrows Primeau LakeIR 192B St.George's Hill 3 IR 192F English River English River IR 192A English River 11 Elak Dase 102 925 Laonil Lake / Seabee Mine 53 11 33 6 IR 219 Lac la Ronge 92 Missinipe Grandmother’s -

Northern Saskatchewan Administration District (NSAD)

Northern Saskatchewan Administration District (NSAD) Camsell Uranium ´ Portage City Stony Lake Athasbasca Rapids Athabasca Sand Dunes Provincial Park Cluff Lake Points Wollaston North Eagle Point Lake Airport McLean Uranium Mine Lake Cigar Lake Uranium Rabbit Lake Wollaston Mine Uranium Mine Lake McArthur River 955 Cree Lake Key Lake Uranium Reindeer Descharme Mine Lake Lake 905 Clearwater River Provincial Park Turnor 914 La Loche Lake Garson Black Lake Point Bear Creek Southend Michel Village St. Brabant George's Buffalo Hill Patuanak Narrows 102 Seabee 155 Gold Mine Santoy Missinipe Lake Gold Sandy Ile-a-la-crosse Pinehouse Bay Stanley Mission Wadin Little Bay Pelican Amyot Lac La Ronge Jans Bay La Plonge Provincial Park Narrows Cole Bay 165 La Ronge Beauval Air Napatak Keeley Ronge Tyrrell Lake Jan Lake Lake 55 Sturgeon-Weir Creighton Michel 2 Callinan Point 165 Dore Denare Lake Tower Meadow Lake Provincial Park Beach Beach 106 969 916 Ramsey Green Bay Weyakwin East 55 Sled Trout Lake Lake 924 Lake Little 2 Bear Lake 55 Prince Albert Timber National Park Bay Prince Albert Whelan Cumberland Little Bay Narrow Hills " Peck Fishing G X Delaronde National Park Provincial Park House NortLahke rLnak eTowns Northern Hamlets ...Northern Settlements 123 Creighton Black Point Descharme Lake 120 Noble's La Ronge Cole Bay Garson Lake 2 Point Dore Lake Missinipe # Jans Bay Sled Lake Ravendale Northern Villages ! Peat Bog Michel Village Southend ...Resort Subdivisions 55 Air Ronge Patuanak Stanley Mission Michel Point Beaval St. George's Hill Uranium -

Diabetes Directory

Saskatchewan Diabetes Directory February 2015 A Directory of Diabetes Services and Contacts in Saskatchewan This Directory will help health care providers and the general public find diabetes contacts in each health region as well as in First Nations communities. The information in the Directory will be of value to new or long-term Saskatchewan residents who need to find out about diabetes services and resources, or health care providers looking for contact information for a client or for themselves. If you find information in the directory that needs to be corrected or edited, contact: Primary Health Services Branch Phone: (306) 787-0889 Fax : (306) 787-0890 E-mail: [email protected] Acknowledgement The Saskatchewan Ministry of Health acknowledges the efforts/work/contribution of the Saskatoon Health Region staff in compiling the Saskatchewan Diabetes Directory. www.saskatchewan.ca/live/health-and-healthy-living/health-topics-awareness-and- prevention/diseases-and-disorders/diabetes Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................... - 1 - SASKATCHEWAN HEALTH REGIONS MAP ............................................. - 3 - WHAT HEALTH REGION IS YOUR COMMUNITY IN? ................................................................................... - 3 - ATHABASCA HEALTH AUTHORITY ....................................................... - 4 - MAP ............................................................................................................................................... -

Saskatchewan Elections: a History December 13Th, 1905 the Liberal Party Formed Saskatchewan’S First Elected Government

SaSkatcheWan EleCtIonS: A History DecemBer 13th, 1905 The Liberal Party formed Saskatchewan’s first elected government. The Liberals were led by Walter Scott, an MP representing the area of Saskatchewan in Wilfred Laurier’s federal government. Frederick Haultain, the former premier of the Northwest Territories, led the Provincial Rights Party. Haultain was linked to the Conservative Party and had advocated for Alberta and Saskatchewan to be one province named Buffalo. He begrudged Laurier for creating two provinces, and fought Saskatchewan’s first election by opposing federal interference in provincial areas of jurisdiction. RESultS: Party Leader Candidates elected Popular vote Liberal Walter Scott 25 16 52.25% Provincial Rights Frederick Haultain 24 9 47.47% Independent 1 - 0.28% Total Seats 25 AuguST 14th, 1908 The number of MLAs expanded to 41, reflecting the rapidly growing population. The Liberals ran 40 candidates in 41 constituencies: William Turgeon ran in both Prince Albert City and Duck Lake. He won Duck Lake but lost Prince Albert. At the time it was common for candidates to run in multiple constituencies to help ensure their election. If the candidate won in two or more constituencies, they would resign from all but one. By-elections would then be held to find representatives for the vacated constituencies. This practice is no longer allowed. RESultS: Party Leader Candidates elected Popular vote Liberal Walter Scott 41 27 50.79% Provincial Rights Frederick Haultain 40 14 47.88% Independent-Liberal 1 - 0.67% Independent 2 - 0.66% Total Seats 41 July 11th, 1912 The Provincial Rights Party morphed into the Conservative Party of Saskatchewan, and continued to campaign for expanding provincial jurisdiction. -

Community Investment in the Pandemic: Trends and Opportunities

Community investment in the pandemic: trends and opportunities Jonathan Huntington, Vice President Sustainability and Stakeholder Relations, Cameco January 6, 2021 A Cameco Safety Moment Recommended for the beginning of any meeting Community investment in the pandemic: trends and opportunities (January 6, 2021) 2 Community investment in the pandemic: Trends • Demand - increase in requests • $1 million Cameco COVID Relief Fund: 581 applications, $17.5 million in requests • Immense competition for funding dollars • We supported 67 community projects across 40 different communities in SK Community investment in the pandemic: trends and opportunities (January 6, 2021) 3 Successful applicants for Cameco COVID Relief Fund Organization Community Organization Community Children North Family Resource Center La Ronge The Generation Love Project Saskatoon Prince Albert Child Care Co-operative Association Prince Albert Lakeview Extended School Day Program Inc. Saskatoon Central Urban Metis Federation Inc. Saskatoon Delisle Elementary School -Hampers Delisle TLC Daycare Inc. Birch Hills English River First Nation English River Beauval Group Home (Shirley's Place) Beauval NorthSask Special Needs La Ronge Nipawin Daycare Cooperative Nipawin Leask Community School Leask Battlefords Interval House North Battleford Metis Central Western Region II Prince Albert Beauval Emergency Operations - Incident Command Beauval Global Gathering Place Saskatoon Northern Hamlet of Patuanak Patuanak Saskatoon YMCA Saskatoon Northern Settlement of Uranium City Uranium City -

Cameco COVID-19 Relief Fund Supports 67 Community Projects

TSX: CCO website: cameco.com NYSE: CCJ currency: Cdn (unless noted) 2121 – 11th Street West, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, S7M 1J3 Canada Tel: 306-956-6200 Fax: 306-956-6201 Cameco COVID-19 Relief Fund Supports 67 Community Projects Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada, April 30, 2020 . Cameco (TSX: CCO; NYSE: CCJ) is pleased to announce that the company is supporting 67 community projects in Saskatoon and northern Saskatchewan through its $1 million Cameco COVID-19 Relief Fund. “There are so many communities and charitable groups hit hard by this pandemic, yet their services are needed now more than ever,” said Cameco president and CEO Tim Gitzel. “We are extremely happy to be able to help 67 of these organizations continue to do the vital work they do every day to keep people safe and supported through this unprecedented time.” Approved projects come from 40 Saskatchewan communities from Saskatoon to the province’s far north. A full listing can be found at the end of this release. Included in the support Cameco is providing are significant numbers of personal protective equipment (PPE) for northern Saskatchewan communities and First Nations – 10,000 masks, 7,000 pairs of gloves and 7,000 litres of hand sanitizer. Donations of supplies and money from nearly 100 Cameco employees augmented the company’s initial $1 million contribution. Cameco will move quickly to begin delivering this support to the successful applicants. “I’m proud of Cameco’s employees for stepping up yet again to support the communities where they live,” Gitzel said. “It happens every time we put out a call for help, a call for volunteers, a call to assist with any of our giving campaigns, and I can’t say enough about their generosity.” Announced on April 15, the Cameco COVID-19 Relief Fund was open to applications from charities, not-for-profit organizations, town offices and First Nation band offices in Saskatoon and northern Saskatchewan that have been impacted by the pandemic. -

Town of La Ronge

TOWN OF LA RONGE P.O. Box 5680 www.laronge.ca La Ronge, Saskatchewan Phone: (306) 425-2066 S0J 1L0 Fax: (306) 425-3883 Accommodation Information Rental, Housing Authority, Real Estate Agents* 00120226223 SASKATCHEWAN LTD. - 87 Irving Street OWNER & Nyle & Lana Wasylenchuk MANAGER: PO Box 357 Air Ronge, SK S0J 3G0 Phone: 306-425-3832 or 306-425-7368 00120226223 SASKATCHEWAN LTD - 112 MacAuley Street OWNER & Nyle & Lana Wasylenchuk MANAGER: PO Box 357 Air Ronge, SK S0J 3G0 Phone: 306-425-3832 or 306-425-7368 AURORA PINES (Townhouses) – 1351, 1352, & 1343 Studer St. OWNER & Kelly or Tracy Fiske MANAGER: PO Box 86 La Ronge, SK S0J 1L0 Phone: 306-425-7886 (Tracy) 306-425-6909 (Kelly) BAYVIEW APARTMENTS - 98 Holmstrup Street OWNER: 10211553 Saskatchewan Ltd MANAGER: Henry Shortt C/O Gary Detwiller Phone: 306-425-4056 PO Box 26025 306-420-0202 Saskatoon, SK S7K 8C1 Fax: 306-425-2656 Phone: 1-306-260-5552 Last Updated: February 8 2017 V:/Center/WORDFILE/ADMIN/Apt- Rental Info 2017 *Information provided voluntarily. List may not be exhaustive BEDROCK MANOR - 108 MacAuley Street OWNER & Mike Vancoughnett MANAGER: 1588 Bliss Crescent Prince Albert, SK. S6V 7J8 Phone: 1-306-922-0997 BURNSON HALL APTS. - 1603 La Ronge Avenue (“Student Housing Only”) OWNER: 10121153 Saskatchewan Ltd MANAGER: Northlands College (Student Housing) c/o Gary Detwiller Attn: Janelle Senga PO Box 26025 PO Box 509 Saskatoon, SK. S7K 8C1 La Ronge, SK S0J 1L0 Phone: 1-306-260-5552 Phone: 306-425-4442 CAMPLING BLK. - 1315 Kowalski Pl. OWNER & Nyle & Lana Wasylenchuk MANAGER: PO Box 357 Air Ronge, SK S0J 3G0 Phone: 306-425-3832 or 306-425-7368 KOWALSKI BLOCK - 1307 Kowalski Place OWNER & Scott Robertson MANAGER: PO Box 360 La Ronge, SK S0J 1L0 Phone: 306-425-2080 LAKEVIEW APARTMENTS - 99 Nunn Street OWNER: Kelly Anderson MANAGER: Moses Charles RR#2 PO Box 1611 Saskatoon, SK S7K 3J5 La Ronge, SK. -

Saskatchewan's Oil and Gas Royalties: a Critical Appraisal by Erin Weir

The SaskatchewanSIPP Institute of Public Policy Saskatchewan's Oil and Gas Royalties: A Critical Appraisal by Erin Weir Public Policy Papers Student Editions From time to time the Institute is in a position to publish papers from students. These papers demonstrate the independent thought of our youth in the field of public policy. While we are pleased to be able to publish this unique body of work,the views expressed are not necessarily the views of the Institute. Table of Contents Contact Information Foreword . .1 Section I: Introduction and Overview . .2 Section II: The Current Royalty Regime . .4 Section III: A Conceptual Model . .6 Section IV: The Short-Term Tradeoff . .11 Section V: The Long-Term Tradeoff . .16 Section VI: Constraints on Royalty Policy . .19 Section VII: Historical Performance Evaluation . .23 Section VIII: Inter-Jurisdictional Performance Evaluation . .29 Section IX: Ideological and Electoral Factors . .32 Section X: Policy Recommendations . .41 PLEASE NOTE – The following sections are available online only at www.uregina.ca/sipp: • Tables I,II,IV and V; • Section XI: Appendices; and, • Section XII: References. Author Erin Weir can be contacted for comment (through April 2003) at: Telephone: (403) 210-7634 E-mail: [email protected] or [email protected] FOREWORD This paper provides a critical appraisal of Saskatchewan’s oil and gas royalties and argues that they should be increased. It was written between June and September of 2002 to convince the provincial government to raise its royalties, rather than to criticize its decision, announced on October 7th, 2002, to greatly reduce them. However, the October 7th announcement makes the paper’s analysis and conclusions all the more timely. -

Final Report

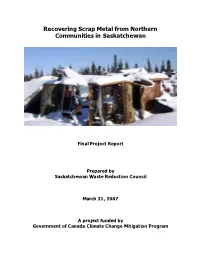

Recovering Scrap Metal from Northern Communities in Saskatchewan Final Project Report Prepared by Saskatchewan Waste Reduction Council March 31, 2007 A project funded by Government of Canada Climate Change Mitigation Program Northern Saskatchewan Scrap Metals Project 2 Background Metal recycling in the southern half of Saskatchewan is fairly well established. Most municipal landfills have a designated area for scrap metals. Some recycling programs include household metals. The collection and recycling of scrap metal from northern communities is hampered by transportation distances and lack of infrastructure. There are metal stockpiles in Saskatchewan’s north, but their locations and volumes have not been systematically catalogued. In addition, there is currently no plan in place to address either the legacy piles or the ongoing accumulation of such materials. Project Objectives The objectives of this project were: • to locate and quantify the extent of metals stockpiled in northern Saskatchewan communities • to conduct a pilot to remove scrap metal from selected communities in order to determine the associated costs of scrap metal recovery in northern Saskatchewan • to investigate potential transportation options, including transportation corridors and backhaul options, to move scrap metals from northern communities to southern markets • to develop an implementation plan for the province that will include recommendations and creative ways of overcoming the barriers to increased recycling of northern/remote scrap metal • to seek the commitment from partners to embrace the scrap metal recovery plan with a view towards ongoing support Results Steering Committee The first task of the project was to bring together a steering committee composed of those knowledgeable about northern communities and those knowledgeable about scrap metal issues. -

Environmental Impact Assessment Notice Section 11 of the Environmental Assessment Act (Saskatchewan) GLR Resources Inc

Environmental Impact Assessment Notice Section 11 of The Environmental Assessment Act (Saskatchewan) GLR Resources Inc. Goldfields Open Pit Mine and Mill, Lake Athabasca GLR Resources Incorporated is proposing open pit mining of the former Box mine deposit at the Goldfields site near Neiman Bay on Lake Athabasca, southeast of Uranium City. On-site milling will use gravity separation and cyanide processing. A lake formerly used for tailings deposits by the Box mine in the 1940’s will be converted to a tailings management pond. A waste rock / ore reject disposal area will be established. Existing road access to the site from Uranium City will be used. GLR requires approval under The Environmental Assessment Act (Saskatchewan) before they can proceed to licensing the project. GLR was directed to conduct an environmental impact assessment and document the results in an environmental impact statement (EIS). The environmental impact assessment is required to assist the Government of Saskatchewan and the public to evaluate the environmental implications of the proposed project. GLR has prepared and revised the EIS and submitted it to the Ministry of Environment for technical review. Based on the EIS, technical review comments have been produced in accordance with the requirements of the The Environmental Assessment Act. Public comment on the environmental impact statement and the Technical Review Comments is invited. Interested individuals may view the documents at the following locations: the University of Regina and University of Saskatchewan -

Leung Sanney Sec. Nc 1996.Pdf (5.876Mb)

EXECUTIVE GOVERNMENT ORGANIZATION IN SASKATCHEWAN AND THE GOVERNMENT ORGANIZATION ACT 1986-87-88 A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in the Department of Political Studies University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Sanney Leung Fall 1996 (c) Copyright Sanney Leung, 1996. All rights reserved. PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for the copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of Political Studies University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, SK S7N OWO i ABSTRACT In the 1986-87-88 session of the Saskatchewan Legislative Assembly, the government of Grant Devine introduced Bill 5 an Act respecting the Organization of the Executive Government of Saskatchewan.