XII. Fighting Against Fusion 1974-1990

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cds by Composer/Performer

CPCC MUSIC LIBRARY COMPACT DISCS Updated May 2007 Abercrombie, John (Furs on Ice and 9 other selections) guitar, bass, & synthesizer 1033 Academy for Ancient Music Berlin Works of Telemann, Blavet Geminiani 1226 Adams, John Short Ride, Chairman Dances, Harmonium (Andriessen) 876, 876A Adventures of Baron Munchausen (music composed and conducted by Michael Kamen) 1244 Adderley, Cannonball Somethin’ Else (Autumn Leaves; Love For Sale; Somethin’ Else; One for Daddy-O; Dancing in the Dark; Alison’s Uncle 1538 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Jazz Improvisation (vol 1) 1270 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: The II-V7-1 Progression (vol 3) 1271 Aerosmith Get a Grip 1402 Airs d’Operettes Misc. arias (Barbara Hendricks; Philharmonia Orch./Foster) 928 Airwaves: Heritage of America Band, U.S. Air Force/Captain Larry H. Lang, cond. 1698 Albeniz, Echoes of Spain: Suite Espanola, Op.47 and misc. pieces (John Williams, guitar) 962 Albinoni, Tomaso (also Pachelbel, Vivaldi, Bach, Purcell) 1212 Albinoni, Tomaso Adagio in G Minor (also Pachelbel: Canon; Zipoli: Elevazione for Cello, Oboe; Gluck: Dance of the Furies, Dance of the Blessed Spirits, Interlude; Boyce: Symphony No. 4 in F Major; Purcell: The Indian Queen- Trumpet Overture)(Consort of London; R,Clark) 1569 Albinoni, Tomaso Concerto Pour 2 Trompettes in C; Concerto in C (Lionel Andre, trumpet) (also works by Tartini; Vivaldi; Maurice André, trumpet) 1520 Alderete, Ignacio: Harpe indienne et orgue 1019 Aloft: Heritage of America Band (United States Air Force/Captain Larry H. -

Michael Brecker Chronology

Michael Brecker Chronology Compiled by David Demsey • 1949/March 29 - Born, Phladelphia, PA; raised in Cheltenham, PA; brother Randy, sister Emily is pianist. Their father was an attorney who was a pianist and jazz enthusiast/fan • ca. 1958 – started studies on alto saxophone and clarinet • 1963 – switched to tenor saxophone in high school • 1966/Summer – attended Ramblerny Summer Music Camp, recorded Ramblerny 66 [First Recording], member of big band led by Phil Woods; band also contained Richie Cole, Roger Rosenberg, Rick Chamberlain, Holly Near. In a touch football game the day before the final concert, quarterback Phil Woods broke Mike’s finger with the winning touchdown pass; he played the concert with taped-up fingers. • 1966/November 11 – attended John Coltrane concert at Temple University; mentioned in numerous sources as a life-changing experience • 1967/June – graduated from Cheltenham High School • 1967-68 – at Indiana University for three semesters[?] • n.d. – First steady gigs r&b keyboard/organist Edwin Birdsong (no known recordings exist of this period) • 1968/March 8-9 – Indiana University Jazz Septet (aka “Mrs. Seamon’s Sound Band”) performs at Notre Dame Jazz Festival; is favored to win, but is disqualified from the finals for playing rock music. • 1968 – Recorded Score with Randy Brecker [1st commercial recording] • 1969 – age 20, moved to New York City • 1969 – appeared on Randy Brecker album Score, his first commercial release • 1970 – co-founder of jazz-rock band Dreams with Randy, trombonist Barry Rogers, drummer Billy Cobham, bassist Doug Lubahn. Recorded Dreams. Miles Davis attended some gigs prior to recording Jack Johnson. -

TOSHIKO AKIYOSHI NEA Jazz Master (2007)

1 Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. TOSHIKO AKIYOSHI NEA Jazz Master (2007) Interviewee: Toshiko Akiyoshi 穐吉敏子 (December 12, 1929 - ) Interviewer: Dr. Anthony Brown with recording engineer Ken Kimery Dates: June 29, 2008 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution Description: Transcript 97 pp. Brown: Today is June 29th, 2008, and this is the oral history interview conducted with Toshiko Akiyoshi in her house on 38 W. 94th Street in Manhattan, New York. Good afternoon, Toshiko-san! Akiyoshi: Good afternoon! Brown: At long last, I‟m so honored to be able to conduct this oral history interview with you. It‟s been about ten years since we last saw each other—we had a chance to talk at the Monterey Jazz Festival—but this interview we want you to tell your life history, so we want to start at the very beginning, starting [with] as much information as you can tell us about your family. First, if you can give us your birth name, your complete birth name. Akiyoshi: To-shi-ko. Brown: Akiyoshi. Akiyoshi: Just the way you pronounced. Brown: Oh, okay [laughs]. So, Toshiko Akiyoshi. For additional information contact the Archives Center at 202.633.3270 or [email protected] 2 Akiyoshi: Yes. Brown: And does “Toshiko” mean anything special in Japanese? Akiyoshi: Well, I think,…all names, as you know, Japanese names depends on the kanji [Chinese ideographs]. Different kanji means different [things], pronounce it the same way. And mine is “Toshiko,” [which means] something like “sensitive,” “susceptible,” something to do with a dark sort of nature. -

A Strayhorn Centennial Salute NJJS Presents an Afternoon of Billy Strayhorn’S Music at Morristown’S Mayo PAC See Page 26

Volume 43 • Issue 7 July/August 2015 Journal of the New Jersey Jazz Society Dedicated to the performance, promotion and preservation of jazz. Michael Hashim leads the Billy Strayhorn Orchestra at the Mayo Performing Arts Center in Morristown on June 14. Photo by Mitchell Seidel. A Strayhorn Centennial Salute NJJS presents an afternoon of Billy Strayhorn’s music at Morristown’s Mayo PAC See page 26. New JerseyJazzSociety in this issue: New JerSey JAzz SocIety Prez Sez. 2 Bulletin Board ......................2 NJJS Calendar ......................3 Jazz Trivia .........................4 Mail Box. 4 Prez Sez Editor’s Pick/Deadlines/NJJS Info .......6 Crow’s Nest. 46 By Mike Katz President, NJJS Change of Address/Support NJJS/ Volunteer/Join NJJS. 47 NJJS/Pee Wee T-shirts. 48 hope that everyone who is reading this is July 31. It will also be a first for us, as Jackie New/Renewed Members ............48 I having a great summer so far and/or has made Wetcher and I will be spending a couple of days StorIeS plans for their upcoming summer vacation. I also there. Billy Strayhorn Tribute ...........cover hope that those plans include the Morristown Jazz At six o’clock, the music turns to the blues with Big Band in the Sky ..................8 and Blues Festival, which will be taking place on the always entertaining Roomful of Blues followed Talking Jazz: Roseanna Vitro. 12 Saturday, August 15 on the Morristown Green. Noteworthy ......................24 by the legendary blues hall of fame harmonica President Emeritus Writes ...........28 The festival is returning for the fifth season and player Charlie Musselwhite and his all-star band 92nd St. -

The Commissioned Flute Choir Pieces Presented By

THE COMMISSIONED FLUTE CHOIR PIECES PRESENTED BY UNIVERSITY/COLLEGE FLUTE CHOIRS AND NFA SPONSORED FLUTE CHOIRS AT NATIONAL FLUTE ASSOCIATION ANNUAL CONVENTIONS WITH A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE FLUTE CHOIR AND ITS REPERTOIRE DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Yoon Hee Kim Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2013 D.M.A. Document Committee: Katherine Borst Jones, Advisor Dr. Russel C. Mikkelson Dr. Charles M. Atkinson Karen Pierson Copyright by Yoon Hee Kim 2013 Abstract The National Flute Association (NFA) sponsors a range of non-performance and performance competitions for performers of all ages. Non-performance competitions are: a Flute Choir Composition Competition, Graduate Research, and Newly Published Music. Performance competitions are: Young Artist Competition, High School Soloist Competition, Convention Performers Competition, Flute Choirs Competitions, Professional, Collegiate, High School, and Jazz Flute Big Band, and a Masterclass Competition. These competitions provide opportunities for flutists ranging from amateurs to professionals. University/college flute choirs perform original manuscripts, arrangements and transcriptions, as well as the commissioned pieces, frequently at conventions, thus expanding substantially the repertoire for flute choir. The purpose of my work is to document commissioned repertoire for flute choir, music for five or more flutes, presented by university/college flute choirs and NFA sponsored flute choirs at NFA annual conventions. Composer, title, premiere and publication information, conductor, performer and instrumentation will be included in an annotated bibliography format. A brief history of the flute choir and its repertoire, as well as a history of NFA-sponsored flute choir (1973–2012) will be included in this document. -

Musica Jazz Autore Titolo Ubicazione

MUSICA JAZZ AUTORE TITOLO UBICAZIONE AA.VV. Blues for Dummies MSJ/CD BLU AA.VV. \The \\metronomes MSJ/CD MET AA.VV. Beat & Be Bop MSJ/CD BEA AA.VV. Casino lights '99 MSJ/CD CAS AA.VV. Casino lights '99 MSJ/CD CAS AA.VV. Victor Jazz History vol. 13 MSJ/CD VIC AA.VV. Blue'60s MSJ/CD BLU AA.VV. 8 Bold Souls MSJ/CD EIG AA.VV. Original Mambo Kings (The) MSJ/CD MAM AA.VV. Woodstock Jazz Festival 1 MSJ/CD WOO AA.VV. New Orleans MSJ/CD NEW AA.VV. Woodstock Jazz Festival 2 MSJ/CD WOO AA.VV. Real birth of Fusion (The) MSJ/CD REA AA.VV. \Le \\grandi trombe del Jazz MSJ/CD GRA AA.VV. Real birth of Fusion two (The) MSJ/CD REA AA.VV. Saint-Germain-des-Pres Cafe III: the finest electro-jazz compilationMSJ/CD SAI AA.VV. Celebrating the music of Weather Report MSJ/CD CEL AA.VV. Night and Day : The Cole Porter Songbook MSJ/CD NIG AA.VV. \L'\\album jazz più bello del mondo MSJ/CD ALB AA.VV. \L'\\album jazz più bello del mondo MSJ/CD ALB AA.VV. Blues jam in Chicago MSJ/CD BLU AA.VV. Blues jam in Chicago MSJ/CD BLU AA.VV. Saint-Germain-des-Pres Cafe II: the finest electro-jazz compilationMSJ/CD SAI Adderley, Cannonball Cannonball Adderley MSJ/CD ADD Aires Tango Origenes [CD] MSJ/CD AIR Al Caiola Serenade In Blue MSJ/CD ALC Allison, Mose Jazz Profile MSJ/CD ALL Allison, Mose Greatest Hits MSJ/CD ALL Allyson, Karrin Footprints MSJ/CD ALL Anikulapo Kuti, Fela Teacher dont't teach me nonsense MSJ/CD ANI Armstrong, Louis Louis In New York MSJ/CD ARM Armstrong, Louis Louis Armstrong live in Europe MSJ/CD ARM Armstrong, Louis Satchmo MSJ/CD ARM Armstrong, Louis -

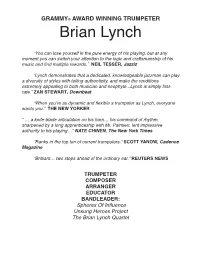

2013 Brian Lynch Full Press Kit(Bio-Discog

GRAMMY© AWARD WINNING TRUMPETER Brian Lynch “You can lose yourself in the pure energy of his playing, but at any moment you can switch your attention to the logic and craftsmanship of his music and find multiple rewards.” NEIL TESSER, Jazziz “Lynch demonstrates that a dedicated, knowledgeable jazzman can play a diversity of styles with telling authenticity, and make the renditions extremely appealing to both musician and neophyte...Lynch is simply first- rate.” ZAN STEWART, Downbeat “When you’re as dynamic and flexible a trumpeter as Lynch, everyone wants you.” THE NEW YORKER “ … a knife-blade articulation on his horn… his command of rhythm, sharpened by a long apprenticeship with Mr. Palmieri, lent impressive authority to his playing…” NATE CHINEN, The New York Times “Ranks in the top ten of current trumpeters.” SCOTT YANOW, Cadence Magazine “Brilliant… two steps ahead of the ordinary ear.” REUTERS NEWS TRUMPETER COMPOSER ARRANGER EDUCATOR BANDLEADER: Spheres Of Influence Unsung Heroes Project The Brian Lynch Quartet Brian Lynch "This is a new millennium, and a lot of music has gone down," Brian Lynch said several years ago. "I think that to be a jazz musician now means drawing on a wider variety of things than 30 or 40 years ago. Not to play a little bit of this or a little bit of that, but to blend everything together into something that has integrity and sounds good. Not to sound like a pastiche or shifting styles; but like someone with a lot of range and understanding." Trumpeter and Grammy© Award Winner Brian Lynch brings to his music an unparalleled depth and breadth of experience. -

Clarence Williams

MUNI 2017-2 – Flute 1-2 Shooting the Pistol (Clarence Williams) 1:26 / 1:17 Clarence Williams Orchestra: Ed Allen-co; Charlie Irvis-tb; possibly Arville Harris-cl, as; Alberto Socarras-fl; Clarence Williams-p; Cyrus St. Clair-tu New York, July 1927 78 Paramount 12517, matrix number 2837-2 / CD Frog DGF37 3 I’ll Take Romance (Ben Oakland) 2:39 Bud Shank-fl; Len Mercer and His Strings Bud Shank With Len Mercer Strings: Giulio Libano (trumpet) Appio Squajella (flute, French horn) Glauco Masetti (alto sax) Bud Shank (alto sax, flute) Eraldo Volonte (tenor sax) Fausto Pepetti (baritone sax) Bruno De Filippi (guitar) Don Prell (bass) Jimmy Pratt (drums) with unidentified harp and strings, Len Mercer (arranger, conductor) Milan, Italy, April 4 & 5, 1958 LP World Pacific WP-1251, Music (It) EPM 20096, LPM 2052 4-5 What’ll I Do (Irving Berlin) 1:26 / 1:23 Bud Shank-fl; Bob Cooper-ob; Bud Shank - Bob Cooper Quintet: Bud Shank (alto sax, flute) Bob Cooper (tenor sax, oboe) Howard Roberts (guitar) Don Prell (bass) Chuck Flores (drums) Capitol Studios, Hollywood, CA, first session, November 29, 1956 LP Pacific Jazz X-634, PJ 1226, matr. ST-1894 / CD Mosaic MS-010 6-7 Flute Bag (Rufus Harley) 2:06 / 2:15 Herbie Mann.fl; Rufus Harley-bagpipes; Roy Ayers (vibes) Oliver Collins (piano) James Glenn (bass) Billy Abner (drums) "Village Theatre", NYC, 2nd show, June 3, 1967 LP Atlantic SD 1497, matr. 12589 8-10 Moment’s Notice (John Coltrane) 4:58 / 1:04 / 0:52 Hubert Laws-fl; Ronnie Laws-ts; Bob James-p, elp, arranger; Gene Bertoncini-g; Ron Carter-b; Steve -

The Ultimate Super Mage ™ by Dean Shomshak

The Ultimate Super Mage ™ by Dean Shomshak HERO PLUS™ The Ultimate Super Mage™ Version 1.1 by Dean Shomshak Editor/Developer: Bruce Harlick Illustrations: Storn Cook Charts: Scott A.H. Ruggels Solitaire Illustration: Greg Smith Pagemaking & Layout: Bruce Harlick Graphic Design: Karl Wu Editorial Contributions: Steve Peterson, Ray Greer, George MacDonald, Steven S. Long Proof Reader: Maggi Perkins Managing Editor: Bruce Harlick Copyright @1996 by Hero Games. All rights reserved. Hero System, Fantasy Hero, Champions, Hero Games and Star Hero are all registered trademarks of Hero Games. Acrobat and the Acrobat logo are trademarks of Adobe Systems Incorporated which may be registered in certain jurisdictions. All other trademarks and registered trademarks are properties of their owners. Published by Hero Plus, a division of Hero Games. Hero Plus Hero Plus is an electronic publishing company, using the latest technology to bring products to customers more efficiently, more rapidly, and at competitive prices. Hero Plus can be reached at [email protected]. Let us know what you think! Send us your mailing address (email and snail mail) and we’ll make sure you’re informed of our latest products. Visit our Web Site at http://www.herogames.com Contents Introduction .............................................7 The White School.............................................. 27 How To Use This Book .................................. 7 The Black School............................................... 27 A Personal Disclaimer................................... -

Savoy and Regent Label Discography

Discography of the Savoy/Regent and Associated Labels Savoy was formed in Newark New Jersey in 1942 by Herman Lubinsky and Fred Mendelsohn. Lubinsky acquired Mendelsohn’s interest in June 1949. Mendelsohn continued as producer for years afterward. Savoy recorded jazz, R&B, blues, gospel and classical. The head of sales was Hy Siegel. Production was by Ralph Bass, Ozzie Cadena, Leroy Kirkland, Lee Magid, Fred Mendelsohn, Teddy Reig and Gus Statiras. The subsidiary Regent was extablished in 1948. Regent recorded the same types of music that Savoy did but later in its operation it became Savoy’s budget label. The Gospel label was formed in Newark NJ in 1958 and recorded and released gospel music. The Sharp label was formed in Newark NJ in 1959 and released R&B and gospel music. The Dee Gee label was started in Detroit Michigan in 1951 by Dizzy Gillespie and Divid Usher. Dee Gee recorded jazz, R&B, and popular music. The label was acquired by Savoy records in the late 1950’s and moved to Newark NJ. The Signal label was formed in 1956 by Jules Colomby, Harold Goldberg and Don Schlitten in New York City. The label recorded jazz and was acquired by Savoy in the late 1950’s. There were no releases on Signal after being bought by Savoy. The Savoy and associated label discography was compiled using our record collections, Schwann Catalogs from 1949 to 1982, a Phono-Log from 1963. Some album numbers and all unissued album information is from “The Savoy Label Discography” by Michel Ruppli. -

It's All Good

SEPTEMBER 2014—ISSUE 149 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM JASON MORAN IT’S ALL GOOD... CHARLIE IN MEMORIAMHADEN 1937-2014 JOE • SYLVIE • BOBBY • MATT • EVENT TEMPERLEY COURVOISIER NAUGHTON DENNIS CALENDAR SEPTEMBER 2014 BILLY COBHAM SPECTRUM 40 ODEAN POPE, PHAROAH SANDERS, YOUN SUN NAH TALIB KWELI LIVE W/ BAND SEPT 2 - 7 JAMES CARTER, GERI ALLEN, REGGIE & ULF WAKENIUS DUO SEPT 18 - 19 WORKMAN, JEFF “TAIN” WATTS - LIVE ALBUM RECORDING SEPT 15 - 16 SEPT 9 - 14 ROY HARGROVE QUINTET THE COOKERS: DONALD HARRISON, KENNY WERNER: COALITION w/ CHICK COREA & THE VIGIL SEPT 20 - 21 BILLY HARPER, EDDIE HENDERSON, DAVID SÁNCHEZ, MIGUEL ZENÓN & SEPT 30 - OCT 5 DAVID WEISS, GEORGE CABLES, MORE - ALBUM RELEASE CECIL MCBEE, BILLY HART ALBUM RELEASE SEPT 23 - 24 SEPT 26 - 28 TY STEPHENS (8PM) / REBEL TUMBAO (10:30PM) SEPT 1 • MARK GUILIANA’S BEAT MUSIC - LABEL LAUNCH/RECORD RELEASE SHOW SEPT 8 GATO BARBIERI SEPT 17 • JANE BUNNETT & MAQUEQUE SEPT 22 • LOU DONALDSON QUARTET SEPT 25 LIL JOHN ROBERTS CD RELEASE SHOW (8PM) / THE REVELATIONS SALUTE BOBBY WOMACK (10:30PM) SEPT 29 SUNDAY BRUNCH MORDY FERBER TRIO SEPT 7 • THE DIZZY GILLESPIE™ ALL STARS SEPT 14 LATE NIGHT GROOVE SERIES THE FLOWDOWN SEPT 5 • EAST GIPSY BAND w/ TIM RIES SEPT 6 • LEE HOGANS SEPT 12 • JOSH DAVID & JUDAH TRIBE SEPT 13 RABBI DARKSIDE SEPT 19 • LEX SADLER SEPT 20 • SUGABUSH SEPT 26 • BROWN RICE FAMILY SEPT 27 Facebook “f” Logo CMYK / .eps Facebook “f” Logo CMYK / .eps with Hutch or different things like that. like things different or Hutch with sometimes. -

SELECTED SOLOS of CHARLIE HADEN: TRANSCRIPTIONS and ANALYSIS

SELECTED SOLOS of CHARLIE HADEN: TRANSCRIPTIONS and ANALYSIS By JONATHAN ZWARTZ A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy (Music) August 2006 School of Music, Faculty of Arts, The Australian National University I hereby state that this thesis is entirely my own original work. Acknowledgements I would like to sincerely thank the following people for their assistance in this folio.Mike Price, Nick Hoorweg, Jenny Lindsay, Dylan Cumow, Jane Lindsay, Peter Dasent, Sally Zwartz. Abstract Charlie Haden is a unique bassist in jazz today. He has an instantly identifiable sound, and broad stylistic taste in both the music that he records and the musicians he records with. The one constant throughout his recorded work is his own distinctive musical style. I was attracted to Charlie Haden’s playing because of his individual approach, particularly his soloing style on more traditional song forms as opposed to the freer jazz forms that he became famous for play ing and soloing on in the earlier part of his career. For the purpose of this analysis, I chose duet settings for the reason that duets are more intimate by nature and perhaps because of that, more revealing. Haden has a reputation for simplicity in his soloing. Indeed, he employs no great theatrical displays of technical virtuosity like other bass soloists. However, my analysis of Haden’s performances show that he is a master soloist in command of his instrument and the musical principles of harmony, melody and rhythm, all incorporated within the particular piece he’s soloing on, coupled with the uncanny ability to ‘tell a story’ when he solos.