Hospital at Home | Guiding Principles for Service Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dental Statistics - NHS Registration and Participation Statistics up to 30 September 2018

Information Services Division Dental Statistics - NHS Registration and Participation Statistics up to 30 September 2018 Publication date 22 January 2019 A National Statistics publication for Scotland Information Services Division This is a National Statistics Publication National Statistics status means that the official statistics meet the highest standards of trustworthiness, quality and public value. They are identified by the quality mark shown above. They comply with the Code of Practice for statistics and are awarded National Statistics status following an assessment by the UK Statistics Authority’s regulatory arm. The Authority considers whether the statistics meet the highest standards of Code compliance, including the value they add to public decisions and debate. Find out more about the Code of Practice at: https://www.statisticsauthority.gov.uk/osr/code-of-practice/ Find out more about National Statistics at: https://www.statisticsauthority.gov.uk/national-statistician/types-of-official-statistics/ 1 Information Services Division Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 3 Main Points ............................................................................................................................ 5 Results and Commentary ....................................................................................................... 6 Registration ....................................................................................................................... -

The Buchanan Centre 126 – 130 Main Street Coatbridge ML5

Church Street Medical Practice The Buchanan Centre 126 – 130 Main Street Coatbridge ML5 3BJ Surgery Opening Hours Monday 8am – 6pm Tuesday 8am – 6pm Wednesday 8am – 6pm Thursday 8am – 6pm Friday 8am – 6pm Saturday and Sunday - Closed In case of EMERGENCY outwith these times telephone 01236 422678 We operate extended hours every Monday and Tuesday between 7.30am to 8.30am and 6pm to 6:45pm. These are strictly pre-booked GP and Nurse appointments only Nearest:- Bus South Circular Road (5 mins) Train Sunnyside Station (10 mins) Coatbridge Central (10 mins) Taxi Main Street (1 min) Car Park Throughout Town Centre (some payable) Telephone: 01236 422678 Fax: 01236 703481 Contents 1.0 Introduction Welcome to the Church Street Practice Page 2 Practice History Page 2 The Doctors Page 2 Practice Nurses Page 3 Administrative Team Page 4 Practice Attached Staff Page 5 2.0 To See Your Doctor Appointments Page 6 Chaperones Page 6 3.0 General Information Telephone System Page 7 Zero Tolerance Page 7 Confidentiality Page 7 Complaints Page 8 Failure to attend Page 9 Home Visits Page 9 Out of Hours Service Page 9 Repeat Prescriptions Page 10 Research/Clinical trials Page 10 Newly Registered Patients Page 10 Carers Page 11 UK Armed Service Veteran Page 11 Change of Address Page 11 Private Medicals Page 11 Disabled Access Page 11 4.0 The Data Protection Act Page 12&13 5.0 Useful Contacts Page 14 1.0 INTRODUCTIONINTRODUCTION Welcome To Church Street Medical Practice This booklet is to welcome you to our practice and to help you gain maximum benefit from the services provided. -

Nhs Lanarkshire Patient Access Policy

NHS LANARKSHIRE PATIENT ACCESS POLICY 1. BACKGROUND NHS Lanarkshire is required by Scottish Government to deliver a consistent, safe, equitable and patient centred service to Lanarkshire patients within national waiting time standards. The current waiting time standards are: • 12 weeks for new outpatient appointment • 6 weeks for the eight diagnostic tests and investigations • 18 weeks Referral to Treatment for 90% of patients • The legal 12 week Treatment Time Guarantee NHS Lanarkshire is required from 1 October 2012 to comply with the Patient Rights (Scotland) Act 2011 that places a legal responsibility on the NHS Board to ensure that all patients due to receive planned treatment on a day case or inpatient basis receive treatment within 12 weeks of the patient agreeing to the treatment. The Patient Access Policy sets out the approach that NHS Lanarkshire will follow to book outpatient, day case, inpatient and diagnostic appointments, what patients can expect in terms of advance notification and the number and type of offers of appointment they can expect to receive. It describes the locations from which services are routinely delivered by NHS Lanarkshire. The Patient Access Policy also sets out the implications to the patient of cancelled appointments and also non-attendance at clinic and /or treatment. In addition, it describes actions available to patients when they are dissatisfied with the service that they receive. NHS Lanarkshire is committed to improving the patient journey and patient experience through improved process, effective use of new technology and through maximising available capacity. Effective communication with patients is essential to achieving that and NHS Lanarkshire will use all available options including letter, email and text to keep in contact with patients. -

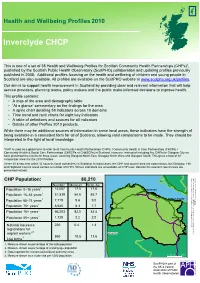

Inverclyde CHCP

Inverclyde CHCP Inverclyde Health 2010 Health and Wellbeing Profiles published by the Scottish Public Observatory Health presented instead. of CHPs number areas andcontain aCouncil Highland areasnestThese autho38 councils within 32 (local comparator areasfor Profiles.2010 the for presentedhave threeareas,results coverin the Community Health &(CHSCPs Social Care Partnerships used toCommu*CHP is all global term toas refer a interpretedin the lightoflocal knowledge. being availablea in consistent form for allofSco While there be may additional sources of informatio This profile contains: serviceproviders, planning teams, policy makers an aim Our is to support health improvement in Scotlan published in Additional2008. profiles focusingon This is setof a one Healthof38 andWellbeing Pro Scotland available.are also All areavailprofiles CHP CHP Population: 80,210 4. Measure shown as a crude rate per 1,000 populati 1,000 perrate crude a as shown Measure 4. author (local council reported for relevant Data 3. popul age working of percentage as shown Measure 2. populat total the of percentage as shown Measure 1. Population Population 75+ years Population 65–74 years Population 16–64 years Population 0–15 years Population Population 85+ years Population 16+ years Live births workers migrant registrations for National insurance • • • • • • ‘At glance’a commentary theon findings for the a Aof thearea map demographyand table A spinechart detailing indicatorsacross59 10 do A table of definitions sourcesand for allindicat Time andtrend rank eightcharts for key indicator Details Profilesof other products.2010 4 2,3 1 1 1 1 1 1 Number Measure Scot. Av. 860220 10.6 1,72966,203 0.4 6,645 2.2 82.5 7,71951,839 8.3 14,007 9.6 64.6 17.5 ity)area g Glasgow North Glasgow North Westg andEast,Glasgow Glasgo on ion rities) in Scotland. -

Appendix 4: a Guide to Public Health

Scottish Public Health Network Appendix 4: A guide to public health Foundations for well-being: reconnecting public health and housing. A Practical Guide to Improving Health and Reducing Inequalities. Emily Tweed, lead author on behalf of the ScotPHN Health and Housing Advisory Group with contributions from Alison McCann and Julie Arnot January 2017 1 Appendix 4: A guide to public health This section aims to provide housing colleagues with a ‘user’s guide’ to the public health sector in Scotland, in order to inform joint working. It provides an overview of public health’s role; key concepts; workforce; and structure in Scotland. 4.1 What is public health? Various definitions of public health have been proposed: “The science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life, and promoting health through the organised efforts of society.” Sir Donald Acheson, 1988 “What we as a society do collectively to assure the conditions in which people can be healthy.” US Institute of Medicine, 1988 “Collective action for sustained population-wide health improvement” Bonita and Beaglehole, 2004 What they have in common is the recognition that public health: defines health in the broadest sense, encompassing physical, mental, and social wellbeing and resilience, rather than just the mere absence of disease; has a population focus, working to understand and influence what makes communities, cities, regions, and countries healthy or unhealthy; recognises the power of socioeconomic, cultural, environmental, and commercial influences on health, and works to address or harness them; works to improve health through collective action and shared responsibility, including in partnership with colleagues and organisations outwith the health sector. -

The Governance of the NHS in Scotland - Ensuring Delivery of the Best Healthcare for Scotland Published in Scotland by the Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body

Published 2 July 2018 SP Paper 367 7th report (Session 5) Health and Sport Committee Comataidh Slàinte is Spòrs The Governance of the NHS in Scotland - ensuring delivery of the best healthcare for Scotland Published in Scotland by the Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body. All documents are available on the Scottish For information on the Scottish Parliament contact Parliament website at: Public Information on: http://www.parliament.scot/abouttheparliament/ Telephone: 0131 348 5000 91279.aspx Textphone: 0800 092 7100 Email: [email protected] © Parliamentary copyright. Scottish Parliament Corporate Body The Scottish Parliament's copyright policy can be found on the website — www.parliament.scot Health and Sport Committee The Governance of the NHS in Scotland - ensuring delivery of the best healthcare for Scotland, 7th report (Session 5) Contents Introduction ____________________________________________________________1 Staff Governance________________________________________________________3 Staff Governance Standard _______________________________________________3 Monitoring views of NHS Scotland staff______________________________________4 Staff Governance - themes raised in evidence ________________________________4 Pressure on staff - what witnesses told us __________________________________5 Consultation and staff relations __________________________________________6 Discrimination, bullying and harassment _________________________________7 Whistleblowing_________________________________________________________8 Confidence to -

![[Name of Public Authority]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8285/name-of-public-authority-308285.webp)

[Name of Public Authority]

SCOTTISH FIRE AND RESCUE SERVICE GUIDE TO INFORMATION AVAILABLE THROUGH THE MODEL PUBLICATION SCHEME 2013 The Freedom of Information (Scotland) Act 2002 (the Act) requires Scottish public authorities to produce and maintain a publication scheme. Authorities are under a legal obligation to: publish the classes of information that they make routinely available tell the public how to access the information and what it might cost. The Scottish Fire and Rescue Service has adopted the Model Publication Scheme 2013 produced by the Scottish Information Commissioner. The scheme has the Commissioner’s approval until 31 May 2017. You can see this scheme on our website or by contacting us at the address below. The purpose of this Guide to Information is to: allow you to see what information is available (and what is not available) in relation to each class. state what charges may be applied. explain how you can find the information easily. provide contact details for enquiries and to get help with accessing the information. explain how to request information we hold that has not been published. Availability and formats The information we publish through the model scheme is, wherever possible, available on our website. We offer alternative arrangements for people who do not want to, or cannot, access the information online or by inspection at our premises. For example, we can usually arrange to send information to you in paper copy (although there may be a charge for this). Exempt information We will publish the information we hold that falls within the classes of information below. If a document contains information that is exempt under Scotland’s freedom of information laws (for example sensitive personal information or a trade secret), we may remove or redact the information before publication but we will explain why. -

GP Registration Form 2020

APPLICATION TO REGISTER PERMANENTLY WITH A GENERAL MEDICAL PRACTICE ALL FIELDS MARKED * ARE MANDATORY AND MUST BE COMPLETED AS FULLY AS POSSIBLE 1. PERSONAL DETAILS ,VWKLV\RXU¿UVWUHJLVWUDWLRQZLWKD Yes No Will you be in the area for more Yes No GP Practice in the UK? than 3 months? ,Iµ1R¶SOHDVHFRPSOHWHDWHPSRUDU\UHVLGHQWIRUP Male * Female * Date of birth * Address * Title * Surname * Forenames * Previous surname * Postcode * Telephone # Email address # Mobile # WKHGDWDVXSSOLHGLQWKHVH¿HOGVZLOOQRWEHLQSXWWRRUXSGDWHGLQWKH&RPPXQLW\+HDOWK,QGH[ &+, EXWZLOOEHKHOGRQWKH*33UDFWLFH¶VV\VWHP The following information can be found on your current medical card : Community Health Index (CHI) number * NHS number * The following information can be found on your ELUWKFHUWL¿FDWH : Town of birth * Country of birth * Registered district of birth Mother’s maiden name 6FRWODQGRQO\ 2. HELP US TO TRACE YOUR PREVIOUS GP HEALTH RECORDS BY PROVIDING THE FOLLOWING INFORMATION Address in UK when you were last registered with a GP * Name and address of previous GP Practice in UK * Postcode * Postcode * If you are from abroad: 'DWH\RX¿UVWFDPHWROLYHLQWKH8. If previously resident in the UK, date of leaving * Your most recent country of residence If you have served in the British Armed Forces: Service Number Enlistment date * Are you a Reservist? Yes No If yes provide your address before enlisting * Leaving date * Postcode * ,VWKLV\RXU¿UVWUHJLVWUDWLRQZLWKD*3VLQFHOHDYLQJWKHDUPHGIRUFHV" Yes No 1 *06*359 3. VOLUNTARY AUTHORISATION FOR ORGAN OR TISSUE DONATION <RXKDYHDFKRLFHDERXWRUJDQRUWLVVXHGRQDWLRQDIWHU\RXUGHDWK7RILQGRXWPRUHDERXWZK\LWLVLPSRUWDQWWKDW\RXWDNHWKHWLPHWRPDNH\RXUGRQDWLRQ GHFLVLRQDQGUHFRUGLWJRWRwww.organdonationscotland.org 4. HOW WE USE INFORMATION The information you have provided will be used by NHS Scotland to carry out its various functions and services including scheduling appointments, ordering tests, hospital referrals and sending correspondence. -

NHS Guidlines

NHSScotland Identity guidelines Identikit Introduction In December 2000, Susan Deacon MSP, In this publication, the Minister said: “The public relate to and recognise Minister for Health and Community Care, the NHS. They believe their care is launched ‘Our National Health: provided by a national health service and staff take pride in the fact that a plan for action, a plan for change’ they work for the NHS. Research tells us that the variety of differently which set out a clear direction for the NHS named NHS bodies confuses the in Scotland with the aims of improving public and alienates staff. As part of our proposals to rebuild the National people’s health and creating a 21st century Health Service we will promote a new identity for the NHS in Scotland.” health service. The guidelines that follow provide an essential design toolkit to establish “Alongside the changes in NHS this new identity. The guidelines cover signage, vehicles, uniforms, stationery, boardrooms, we will re-establish literature, forms and other items. The a national identity for the aim is to replace, over time, the array of existing identities within NHS NHS in Scotland.” organisations with the single NHS identity while avoiding wastage and unnecessary expenditure. Our National Health: a plan for action, a plan for change section 3/page 31 2 Contents Section 1 Our national identity 4 Exclusion zone 6 Minimum size 6 Section 2 Identity structure 7 Essential elements 9 Identity variants 10 Caring device 12 Positioning the identity 14 Other identities 15 Working in partnership 16 Section 3 Identities for ideas & initiatives 17 Initiatives 18 Section 4 NHSScotland typefaces 19 Stone Sans 20 Arial 24 Garamond 25 Times New Roman 26 Literature 27 Section 5 Colour 28 Using colour 29 Primary colours 30 Colour palette 31 Tints 32 Printing the identity 33 3 Section One Our national identity Together, the initials ‘NHS’ and the caring symbol form the foundations of our identity. -

HMICS Effective Practice Submission

HMICS Effective Practice submission Title Strathclyde Police and Grampian Police Body Worn Video Force Details CI John Laing, Strathclyde Police, CI Nick Topping, Grampian Police What was the problem / Targeting violence and anti-social behaviour is a national operational priority of the issue Scottish Policing Assessment 2011/15 which contributes to the Scottish Government National Outcome “we live our lives safe from crime disorder and danger. It is also a force and local policing priority which features in local authority single outcome agreements and community planning partnership strategies. Renfrewshire was chosen for this initiative as it has a particularly high level of violence and anti-social behaviour and has a number areas of deprivation including Ferguslie Park (ranked 2 in the SIMD 2009) . Its geography also includes rural areas that are not served by fixed site cctv systems and a number of cycle tracks where mobile cctv is ineffective. Northfield/Mastrick in Grampian were similarly chosen for high levels of violence as well as being one of the most socially deprived in the force area. Public space CCTV plays a significant role in the prevention, detection and prosecution of crime (A national strategy for CCTV in Scotland 2011). Research into a previous National pilot of BWV by the Home Office Police and Crime Standards Directorate (Guidance for the Police use of Body Worn Video Devices - July 2007) highlighted some early results in terms of crime reduction and increased public reassurance as well as reductions in paperwork and court attendance from increased guilty pleas associated with the use of this technology. -

NHS Grampian Community Pharmacist Locum Information Pack

NHS Grampian Community Pharmacist Locum Information Pack NHS Grampian Community Pharmacist Locum Information Pack Contents Page No 1. The Pharmacy and Medicines Directorate (P&MD) ......................................... 3 2. Controlled Drug Accountable Officers Team .................................................... 3 3. To Register as a Locum ................................................................................... 3 4. NHS Mail Account ............................................................................................ 3 5. PCR Login ........................................................................................................ 3 6. Community Pharmacy Website ........................................................................ 4 7. Community Pharmacy Services and Associated Patient Group Directions (PGDs)........................................................................................................................ 4 8. Locally Negotiated Services ............................................................................. 8 9. Palliative Care Network .................................................................................. 10 10. Special Preparations and Unlicensed Medicines ........................................... 10 11. Storage of vaccines & refrigerated products .................................................. 11 12. Central Stores - Order Forms ......................................................................... 11 13. Translation Tools .......................................................................................... -

Anticipatory Care Planning in Scotland

Anticipatory Care Planning in Scotland Supporting people to plan ahead and discuss their wishes for future care March 2020 © Healthcare Improvement Scotland 2020 Published March 2020 This document is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Licence. This allows for the copy and redistribution of this document as long as Healthcare Improvement Scotland is fully acknowledged and given credit. The material must not be remixed, transformed or built upon in any way. To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ www.healthcareimprovementscotland.org 1 Contents Contents ..................................................................................................................................... 2 Summary .................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 4 Anticipatory Care Planning ........................................................................................................ 5 Adopting ACP in Scotland .......................................................................................................... 6 Anticipatory Care Plans – evidence review ............................................................................. 10 How can we further improve ACP in Scotland? ......................................................................