Pedro's Patter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

June 2015 2 a Letter from the Chairman

The Rotating Beacon The Newsletter of the UK Section of IFFR June 2015 2 A letter from the Chairman Dear Flying Rotarians It’s almost half way through the was an eye opening experience to flying year and I have been privi- witness the dedication of a thor- leged to attend a number of excel- oughly dedicated trainer and his staff lent flying events. We started the as they brought the horses in their year with a visit to the RAF Mu- care into peak condition. seum at Cosford. The threatened CBs and heavy showers restricted Angus and I have also managed to the number flying in and those that join the German/Austrian Section at did made an early get away. The Kassel and the Benelux Section at museum is an amazing place. I Ypres. I found the latter weekend a never knew that the UK built so most moving experience. To see the many different aircraft in the post simple inscription “Known unto war period. Many were prototypes God” on so many grave stones was while others went into production something I will never forget. but had a limited run. One of these was the Short Belfast where only Looking forward to the second part of 10 were built. The significance of the year Alan Peaford has set up an the one on display was that one of outstanding meeting at Biggin Hill on our members who was there, Colin September 15. I cannot imagine a Ferguson, had flown it during his fuller day of flying related activity. -

RAM Index As at 1 September 2021

RAM Index As at 1 September 2021. Use “Ctrl F” to search Current to Vol 74 Item Vol Page Item Vol Page This Index is set out under the Aircraft armour 65 12 following headings. Airbus A300 16 12 Airbus A340 accident 43 9 Airbus A350 37 6 Aircraft. Airbus A350-1000 56 12 Anthony Element. Airbus A400 Avalon 2013 2 Airbus Beluga 66 6 Arthur Fry Airbus KC-30A 36 12 Bases/Units. Air Cam 47 8 Biographies. Alenia C-27 39 6 All the RAAF’s aircraft – 2021 73 6 Computer Tips. ANA’s DC3 73 8 Courses. Ansett’s Caribou 8 3 DVA Issues. ARDU Mirage 59 5 Avro Ansons mid air crash 65 3 Equipment. Avro Lancaster 30 16 Gatherings. 69 16 General. Avro Vulcan 9 10 Health Issues. B B2 Spirit bomber 63 12 In Memory Of. B-24 Liberator 39 9 Jeff Pedrina’s Patter. 46 9 B-32 Dominator 65 12 John Laming. Beaufighter 61 9 Opinions. Bell P-59 38 9 Page 3 Girls. Black Hawk chopper 74 6 Bloodhound Missile 38 20 People I meet. 41 10 People, photos of. Bloodhounds at Darwin 48 3 Reunions/News. Boeing 307 11 8 Scootaville 55 16 Boeing 707 – how and why 47 10 Sick Parade. Boeing 707 lost in accident 56 5 Sporting Teams. Boeing 737 Max problems 65 16 Squadrons. Boeing 737 VIP 12 11 Boeing 737 Wedgetail 20 10 Survey results. Boeing new 777X 64 16 Videos Boeing 787 53 9 Where are they now Boeing B-29 12 6 Boeing B-52 32 15 Boeing C-17 66 9 Boeing KC-46A 65 16 Aircraft Boeing’s Phantom Eye 43 8 10 Sqn Neptune 70 3 Boeing Sea Knight (UH-46) 53 8 34 Squadron Elephant walk 69 9 Boomerang 64 14 A A2-295 goes to Scottsdale 48 6 C C-130A wing repair problems 33 11 A2-767 35 13 CAC CA-31 Trainer project 63 8 36 14 CAC Kangaroo 72 5 A2-771 to Amberley museum 32 20 Canberra A84-201 43 15 A2-1022 to Caloundra RSL 36 14 67 15 37 16 Canberra – 2 Sqn pre-flight 62 5 38 13 Canberra – engine change 62 5 39 12 Canberras firing up at Amberley 72 3 A4-208 at Oakey 8 3 Caribou A4-147 crash at Tapini 71 6 A4-233 Caribou landing on nose wheel 6 8 Caribou A4-173 accident at Ba To 71 17 A4-1022 being rebuilt 1967 71 5 Caribou A4-208 71 8 AIM-7 Sparrow missile 70 3 Page 1 of 153 RAM Index As at 1 September 2021. -

Autumn 2017 Editor and Contributing Author: Gordon R Birkett

ADF Serials Telegraph News News for those interested in Australian Military Aircraft History and Serials Volume 7: Issue 2: Autumn 2017 Editor and contributing Author: Gordon R Birkett, Message Starts: In this Issue: News Briefs: from various sources. Gordon Birkett @2016 Story: RAAF AIRCRAFT MARKINGS SINCE 1950 SQUADRON MARKINGS – PART 2- The Canberra: by John Bennett @2016 Story: The Losses of Coomalie 43,it Could Have Been a Lot Worse by Garry "Shep" Shepherdson @2016 Story: Striking the Japanese, before and after the Doolittle Raid, and a Aussie witness to the big Bomb Written by Gordon Birkett @2017 Story : The fatigue failure of seemingly minor components: Loss of F-111C A8-136 : Written by Gordon R Birkett@2016 Curtiss Wright Corner: P-40E-CU A29-78 : Gordon R Birkett@2016 Odd Shots Special: Supermarine Spitfire MkVC RAAF Crack ups Gordon R Birkett@2016 Message Traffic Selections: Please address any questions to: [email protected] Message Board – Current hot topics: These boards can be accessed at: www.adf-messageboard.com.au/invboard/ News Briefs 16th December 2016: The small fleet of four Australian based C-27J aircraft of No 35 Squadron, RAAF , based at Richmond, NSW, has attained initial Operational Capability (IOC) on this date 18th December 2016: 0609hrs, TNI-AU C-130H A-1334 crashed, killing all 13 on board in the mountainous district of Minimo, Jayawijaya after taking off from Timika, West Papua Province. This particular aircraft was Ex RAAF A97-005 which was handed over to the TNI-AU, only ten months prior, on the 8th February 2016. -

Part 2 — Aircraft Type Designators (Decode) Partie 2 — Indicatifs De Types D'aéronef (Décodage) Parte 2 — Designadores De Tipos De Aeronave (Descifrado) Часть 2

2-1 PART 2 — AIRCRAFT TYPE DESIGNATORS (DECODE) PARTIE 2 — INDICATIFS DE TYPES D'AÉRONEF (DÉCODAGE) PARTE 2 — DESIGNADORES DE TIPOS DE AERONAVE (DESCIFRADO) ЧАСТЬ 2. УСЛОВНЫЕ ОБОЗНАЧЕНИЯ ТИПОВ ВОЗДУШНЫХ СУДОВ ( ДЕКОДИРОВАНИЕ ) DESIGNATOR MANUFACTURER, MODEL DESCRIPTION WTC DESIGNATOR MANUFACTURER, MODEL DESCRIPTION WTC INDICATIF CONSTRUCTEUR, MODÈLE DESCRIPTION WTC INDICATIF CONSTRUCTEUR, MODÈLE DESCRIPTION WTC DESIGNADOR FABRICANTE, MODELO DESCRIPCIÓN WTC DESIGNADOR FABRICANTE, MODELO DESCRIPCIÓN WTC УСЛ . ИЗГОТОВИТЕЛЬ , МОДЕЛЬ ВОЗДУШНОГО WTC УСЛ . ИЗГОТОВИТЕЛЬ , МОДЕЛЬ ВОЗДУШНОГО WTC ОБОЗНАЧЕНИЕ ОБОЗНАЧЕНИЕ A1 DOUGLAS, Skyraider L1P M NORTH AMERICAN ROCKWELL, Quail CommanderL1P L DOUGLAS, AD Skyraider L1P M NORTH AMERICAN ROCKWELL, A-9 Sparrow L1P L DOUGLAS, EA-1 Skyraider L1P M Commander NORTH AMERICAN ROCKWELL, A-9 Quail CommanderL1P L A2RT KAZAN, Ansat 2RT H2T L NORTH AMERICAN ROCKWELL, Sparrow CommanderL1P L A3 DOUGLAS, TA-3 Skywarrior L2J M DOUGLAS, NRA-3 SkywarriorL2J M A10 FAIRCHILD (1), OA-10 Thunderbolt 2 L2J M DOUGLAS, A-3 Skywarrior L2J M FAIRCHILD (1), A-10 Thunderbolt 2L2J M FAIRCHILD (1), Thunderbolt 2L2J M DOUGLAS, ERA-3 SkywarriorL2J M AVIADESIGN, A-16 Sport Falcon L1P L DOUGLAS, Skywarrior L2J M A16 AEROPRACT, A-19 L1P L A3ST AIRBUS, Super Transporter L2J H A19 AIRBUS, Beluga L2J H A20 DOUGLAS, Havoc L2P M DOUGLAS, A-20 Havoc L2P M AIRBUS, A-300ST Super TransporterL2J H AEROPRACT, Solo L1P L AIRBUS, A-300ST Beluga L2J H A21 SATIC, Beluga L2J H AEROPRACT, A-21 Solo L1P L SATIC, Super Transporter L2J H A22 SADLER, Piranha -

Print This Page

RAAF Radschool Association Magazine – Vol 39 Page 12 Iroquois A2-1022 On Friday the 16th March, 2012, an Iroquois aircraft with RAAF serial number A2-1022, was ceremoniously dedicated at the Caloundra (Qld) RSL. Miraculously, it was the only fine day that the Sunshine Coast had had for weeks and it hasn't stopped raining since. It was suggested that the reason for this was because God was a 9Sqn Framie in a previous life. A2-1022 was one of the early B model Iroquois aircraft purchased and flown by the RAAF and in itself, was not all that special. The RAAF bought the B Models in 3 batches, the 300 series were delivered in 1962, the 700 series in 1963 and the 1000 series were delivered in 1964. A2- 1022 was of the third series and was just an Iroquois helicopter, an airframe with an engine, rotor, seats etc, much the same as all the other sixteen thousand or so that were built by the Bell helicopter company all those years ago – it was nothing out of the ordinary. So why did so many people give up their Friday to come and stand around in the hot sun for an hour or more just to see this one?? The reason they did was because there is quite a story associated with this particular aircraft and as is usually the case, the story is more about the people who flew it, flew in it and who fixed it – not about the aircraft itself. It belonged to 9 Squadron which arrived in Vietnam, in a roundabout route, in June 1966 with 8 of this type of aircraft and was given the task of providing tactical air transport support for the Australian Task Force. -

THE RAAF at Long Tan

THE RAAF AT Long Tan DR CHRIS CLARK THE RAAF AT LONG TAN Dr Chris Clark This paper is an edited transcript of a seminar that was presented on behalf of the Air Power Development Centre on Wednesday, 20 July 2010. August 18 marks the anniversary of the Battle actually demonstrates that it has been this way for of Long Tan in 1966, which was arguably the most many decades. Given the unprepared circumstances famous action fought during the ten-year Australian in which D Company found itself forced to mount a commitment to the Vietnam War. While some other defence, it was only logical that survival would depend actions, such as the battle for the fire support bases upon the support the infantry could obtain from other Coral and Balmoral in May 1968, were probably elements of 1ATF, and even allied forces in the area. comparable in size and ferocity, these are not so well This it got from a regiment of 105mm howitzers, one known and certainly not as celebrated. It was at Long unit of which was a New Zealand battery, operating Tan that D Company of 6th Battalion, Royal Australian from the task force base at Nui Dat, and also from a Regiment (6RAR), part of the 1st Australian Task US battery of 155mm medium guns. The artillery Force (1ATF), encountered an enemy force believed ended up firing some 3500 rounds over the course of to have numbered between 2500 and 3000 Viet Cong the battle, an average of about 20 rounds a minute. and resisted annihilation for some three hours until reached by relieving forces. -

BULLETIN PO Box 5784 Stafford Heights 4053 Website

ROYAL AUSTRALIAN SURVEY CORPS ASSOCIATION Queensland Branch BULLETIN PO Box 5784 Stafford Heights 4053 Website: www.rasurvey.org ANZAC EDITION – No 52 APRIL 2013 CALENDER 2013 25 April – Anzac Day – Dawn service at Enoggera (location TBA) and City march. 26 May – Gourmet BBQ at the home of Tony & Loretta Gee (to be confirmed) 27 June – Colonel Alex Laing Memorial Dinner at the United Service Club. 7 September – Annual Reunion and AGM (location TBA) December – Drinks at I Topo and Derek Chambers Award presentation. ANZAC DAY Join your mates for our Anzac Day celebration on Wednesday 25 April. Again we start with the Dawn Service at 0500h at the Enoggera Engineer Memorial –.now relocated temporally to the vicinity of the old 8/9 Battalion area. The previous 2CER buildings including the Sportman’s Club fronting Samford Road have been demolished for re-building. Our President Alex Cairney is to place the Association wreath. Further details on Dawn Service location will be emailed to Brisbane based members later. WW2 veterans will march ‘in block’ at the front with those who cannot march following in busses or vehicles. The City parade commences at 1000h with the Air Force leading, then Navy then Army.. RASvy Associationn is listed as number 63 in the post WW2 group, which means we should step off not later than1030h but best be there by 1000h. We are positioned immediately after the Aust Water Tpt Assn and before the RASigs Assn . FUP is in George St. between Charlotte and Elizabeth Streets. Keep an eye open for our distinctive Banner. -

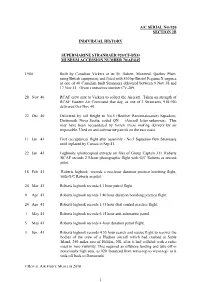

A/C Serial No.920 Section 2B

A/C SERIAL NO.920 SECTION 2B INDIVIDUAL HISTORY SUPERMARINE STRANRAER 920/CF-BXO MUSEUM ACCESSION NUMBER 70/AF/645 1940 Built by Canadian Vickers at its St. Hubert, Montreal, Quebec Plant, using British equipment, and fitted with 810 hp Bristol Pegasus X engines as one of 40 Canadian built Stranraers delivered between 9 Nov 38 and 17 Nov 41. Given contractors number CV-209. 28 Nov 40 RCAF crew sent to Vickers to collect the Aircraft. Taken on strength of RCAF Eastern Air Command that day, as one of 3 Stranraers, 918-920 delivered Oct-Nov 40. 22 Dec 40 Delivered by rail freight to No.5 (Bomber Reconnaissance) Squadron, Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, coded QN (Aircraft letter unknown). This may have been necessitated by frozen rivers making delivery by air impossible. Used on anti-submarine patrols on the east coast. 11 Jan 41 First (acceptance) flight after assembly - No.5 Squadron flew Stranraers until replaced by Cansos in Sep 41. 22 Jan 41 Logbooks (photocopied extracts on file) of Group Captain J.H. Roberts RCAF records 2.5-hour photographic flight with G/C Roberts as second pilot. 18 Feb 41 Roberts logbook records a two-hour duration practice bombing flight, with G/C Roberts as pilot. 24 Mar 41 Roberts logbook records 4.1 hour patrol flight. 9 Apr 41 Roberts logbook records 1.40 hour duration bombing practice flight. 24 Apr 41 Roberts logbook records 1.35 hour dual control practice flight. 1 May 41 Roberts logbook records 6.15 hour anti-submarine patrol. 5 May 41 Roberts logbook records 4-hour duration patrol flight. -

No. 82 Wing RAAF

Article Talk Read Edit View history Search Wikipedia No. 82 Wing RAAF From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia No. 82 Wing is the strike and reconnaissance wing of the Royal Australian Air Force Main page No. 82 Wing RAAF Contents (RAAF). It is headquartered at RAAF Base Amberley, Queensland. Coming under Featured content the control of Air Combat Group, the wing operates F/A-18F Super Hornet multirole Current events fighters and Pilatus PC-9 forward air control aircraft. Its units include Nos. 1 and 6 Random article Squadrons, operating the Super Hornet, and No. 4 Squadron, operating the PC-9. Donate to Wikipedia Wikipedia store Formed in August 1944, No. 82 Wing operated B-24 Liberator heavy bombers in the South West Pacific theatre of World War II. Initially comprising two flying units, Interaction Nos. 21 and 24 Squadrons, the wing was augmented by 23 Squadron in 1945. After Help the war its operational units became Nos. 1, 2 and 6 Squadrons. It re-equipped with About Wikipedia Avro Lincolns in 1948 and, from 1953, English Electric Canberra jets. Both types Community portal No. 82 Wing's crest saw action in the Malayan Emergency during the 1950s; the Canberras were also Recent changes Active 1944–current Contact page deployed in the Vietnam War from 1967 to 1971. Country Australia Between 1970 and 1973, as a stop-gap pending delivery of the long-delayed Tools Branch Royal Australian Air Force General Dynamics F-111C swing-wing bomber, Nos. 1 and 6 Squadrons flew leased What links here Role Precision strike; reconnaissance Related changes F-4E Phantoms. -

The Bloated Aircraft Industry the Aircraft Workers Protest Decided

THE ECONOMIC WEEKLY January 23, 1965 to the Chief Minister, is also not with the Centre. What will be tried though, siderations will dictate petty favours, out significance. are small acts of defiance, which if nobody seems to be particularly pushed through, could build confi bothered. And the opposition is still* It is now rumoured that a new align dence, rally the cohorts and lead to weak enough to be treated as irrele ment is taking shape in the Andhra bigger things. vant. Congress power elite. A C Subba Reddy from Nellore and a strong man But what is all the quarrel about? All this is creating a vacuum both in his own right seems to be emerging Perhaps, Sanjeeva Reddy is all for the inside the Congress and in the South as the direct plenipotentiary of Andh- Durgapur line while Brahmananda as a whole. It is a peculiar problem ra's man in the all-India Syndicate. Reddy insists on loyalty to the Bhuba- since the vacuum seems pretty full of Against this powerful combination, neswar approach? Even to pose the noises, scramblings, posturings and the Brahmananda Reddy is forming an axis conflict in this context causes Homeric like. Moreover, if nature is said to with APCC President Thimma Reddy mifth. To their credit it must be abhore vacuum the Congress politi and Finance Minister Chenna Reddy. said that the protagonists do not even cians seem to thrive within one. The These positions have not crystallised take the trouble to put on any ideo danger is that the people may well as yet and each is rather warily feel logical togas. -

The Perennial Thorn

MIKE HOOKS Shorts: THE PERENNIAL THORN In his latest article on the political aspects of some of the most significant episodes in the evolution of Britain’s post-war aircraft industry, Prof KEITH HAYWARD FRAeS turns his attention to a company that posed a particularly awkward problem for several UK govern- ments owing to its unique ownership structure and politically sensitive geographical location HORT BROTHERS, often abbreviated & Harland Ltd, sponsored by the Air Ministry, just to Shorts, was a thorny problem before moving entirely to Belfast in 1948. for successive British governments. The post-1945 environment was not kind to As a uniquely state-owned aircraft Shorts. Its flying-boat expertise was obsolete and manufacturer from 1943 — and later its comparatively conventional design offering Slocated in Northern Ireland, a politically sensitive for the “V-bomber” specification — the Sperrin — part of the UK — Shorts faced a problematic was quickly superseded by Vickers’ Valiant. The future that could not be left to the “invisible company’s single-engined carrier-based Seamew ABOVE Shorts designed and built two prototypes — XG900 and XG905 — of the S.C.1 experimental jet-powered vertical take-off and landing (VTOL) aircraft, fitted with four vertical-lift engines and one horizontally mounted for hand” of market forces. This kept the company anti-submarine aircraft was not a success either. conventional flight. Both had completed transitional flights from vertical to horizontal flight by the end of 1960. out of both the rationalisation of the 1960s and One bright spot, however, was the development later, nationalisation in the 1970s. The political of a capability in electronic technology that a 15 per cent share of Shorts in support of the a link with a mainland company remained context of Shorts was acutely underlined by the would eventually provide an entrée into work Britannia contract. -

Empennage Statistics and Sizing Methods for Dorsal Fins

AERO_TN_TailSizing_13-04-15 Aircraft Design and Systems Group (AERO) Department of Automotive and Aeronautical Engineering Hamburg University of Applied Sciences Berliner Tor 9 D - 20099 Hamburg Empennage Statistics and Sizing Methods for Dorsal Fins Priyanka Barua Tahir Sousa Dieter Scholz 2013-04-15 Technical Note AERO_TN_TailSizing_13-04-15 Dokumentationsblatt 1. Berichts-Nr. 2. Auftragstitel 3. ISSN / ISBN AERO_TN_TailSizing Airport2030 --- (Effizienter Flughafen 2030) 4. Sachtitel und Untertitel 5. Abschlussdatum Empennage Statistics and 2013-04-15 Sizing Methods for Dorsal Fins 6. Ber. Nr. Auftragnehmer AERO_TN_TailSizing 7. Autor(en) (Vorname, Name, E-Mail) 8. Förderkennzeichen Priyanka Barua 03CL01G Tahir Sousa 9. Kassenzeichen Dieter Scholz 810302101951 10. Durchführende Institution (Name, Anschrift) 11. Berichtsart Aircraft Design and Systems Group (AERO) Technische Niederschrift Department Fahrzeugtechnik und Flugzeugbau 12. Berichtszeitraum Fakultät Technik und Informatik 2012-10-15 – 2013-04-15 Hochschule für Angewandte Wissenschaften Hamburg (HAW) Berliner Tor 9, D - 20099 Hamburg 13. Seitenzahl 145 14. Auftraggeber (Name, Anschrift) 15. Literaturangaben Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF) 81 Heinemannstraße 2, D - 53175 Bonn - Bad Godesberg 16. Tabellen 48 Projektträger Jülich Forschungszentrum Jülich GmbH 17. Bilder Wilhelm-Johnen-Straße, D - 52438 Jülich 76 18. Zusätzliche Angaben Sprache: Englisch. URL: http://Reports_at_AERO.ProfScholz.de 19. Kurzfassung Dieser Bericht beschreibt verbesserte Methoden zur Abschätzung von Parametern des Höhen- und Seitenleitwerks. Weiterhin werden parameter der Rückenflossen aus den Parametern des a aSeitenleitwerks abgeleitet um den Vorentwurf zu unterstützen. Basis sind Statistiken aufbauend auf aDaten, die aus Dreiseitenansichten gewonnen werden. Die betrachteten Parameter sind Leitwerksvolumenbeiwert,a Streckung, Zuspitzung, Pfeilwinkel, relative Profildicke für Höhen- und Seitenleitwerk,a sowie die Profiltiefe und Spannweite von Höhen- und Seitenruder.