Cake and Cockhors€

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Village Magazine for Byfield December/January 2021

The Byword A Village Magazine for Byfield December/January 2021 We wish all our readers a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year Magazine and Parish Information A magazine published by Holy Cross Church, Byfield, for all the residents in the village. The magazines are issued in February, April, June, August, October and December. Contributions are always welcome: copy to the Editor by the first Sunday of the preceding month, please. Editor: Miss Pam Hicks ([email protected]) Tel: 261257 Advertising: Mrs Lyn Grennan, 35 The Twistle Tel: 261596 Distribution: Mrs Lyn Grennan, 35 The Twistle Tel: 261596 Parish Church of Holy Cross: Rector Lay Reader Mrs Lesley Palmer Tel: 264374 Churchwardens: Mrs Chris Cross, 28 Bell Lane Tel: 260764 Mrs Lyn Grennan, 35 The Twistle Tel: 261596 Hon. Treasurer: Miss Pam Hicks, 1 Edwards Close Tel: 261257 Deputy Treasurer: Mrs Diana Charters Tel: 261725 Baptisms, Banns, Marriages, Funerals: Contact a churchwarden as above Choir Practice: Wednesdays at 7.00pm. Organist: Choir Mistress: Mrs Alison Buck ([email protected]) Tel: 260977 Bell ringing Practice: Fridays at 7.30pm but suspended at present due to Covid-19 Tower Captain: Mr James Grennan Tel: 261596 Methodist Church: Minister: Revd. Lin Francis ([email protected]) Tel: 01295 262602 R.C. Church of the Sacred Heart, Main Street, Aston le Walls: Parish Priest: Father John Conroy, The Presbytery, Aston le Walls Tel: 01295 660592 Stagecoach (Banbury) 01865 772250 Useful Telephone Numbers TRANSCO Gas 0800 111 999 Anglian Water 0800 771 881 Byfield Medical -

Sunshine Tour 2021 List of Registered Venues

Sunshine Tour 2021 List of Registered Venues *To search for a venue - type 'CTRL F' and type the centre/county name or address. Show/Club/Centre County Show Address Post Code Website Clarence Esplanade, Southsea, All Stars Jumping Events Hampshire Portsmouth PO5 3PE All Stars jumping events Facebook Graceland'S Equestrian Centre, Crutch Alvechurch Riding Club Worcestershire Lane, Elmbridge, Droitwich WR9 0BR www.alvechurchridingclub.co.uk Sallow Lane, Larling Anvil Park Stud Norfolk NR16 2QU www.anvil-park-stud.co.uk APHS London Counties Horse Pachesham Equestrian Centre Show Surrey KT22 0AL www.aphs.org.uk Astley Show Field, Astley Lane, Ardsley Horse And Pony Club West Yorkshire Swillington, Leeds LS26 8HF www.ardsleyhpc.co.uk Gaston Farm, School Hill, Slindon , Arundel And District Riding Club West Sussex Arundel BN18 0RS www.arundelridingclub.com Aspley Guise And District Riding Wing Dressage & Jumping Centre, Club Bedfordshire Cublington Road, Leighton Buzzard LU7 0LB www.aspleyguiseridingclub.com Aspley Guise And District Riding Addington Equestrian Centre, Club Bedfordshire Buckinghamshire MK18 2JR www.aspleyguiseridingclub.com Barleylands Ec Barleylands Road Basildon Barleylands Arena Essex Essex SS15 4BG Www.barleylandsarena.co.uk Main Road Rettendon Common Beechwood Equestrian Centre Essex CM38DY Beechwood Equestrian Centre Fairoak Grange Equestrian Centre, Berkshire County Riding Club Berkshire Ashford Hill, Berkshire RG19 8BL www.berkscountyrc.co.uk The Polegrove, Brockley Road, Bexhill On Bexhill Horse Show East Sussex Sea -

LAND SOUTH of WOOD FORD ROAD, BYFIELD, N ORTHAMPTONSHIRE Residential Travel Plan

LAND SOUTH OF WOODFORD ROAD, BYFIELD, NORTHAMPTONSHIRE Residential Travel Plan – Revision A LAND SOUTH OF WOODFORD ROAD, BYFIELD, NORTHAMPTONSHIRE, NN11 6XD Residential Travel Plan Revision A Revision A Revision – Client: Byfield Medical Centre Engineer: Create Consulting Engineers Ltd ROAD, BYFIELD, NORTHAMPTONSHIRE 109-112 Temple Chambers Travel Plan 3-7 Temple Avenue London EC4Y 0HA Tel: 020 7822 2300 Email: [email protected] Web: www.createconsultingengineers.co.uk Residential Report By: Fiona Blackley, MA (Hons), MSc, MCIHT, MILT Checked By: Sarah Simpson, BA (Hons), MSc (Eng), CEng, MCIHT Reference: FB/CC/P16-1149/01 Rev A Date: February 2017 LAND SOUTH OF WOODFORD OF LAND SOUTH Land South of Woodford Road, Byfield, Northamptonshire, NN11 6XD Residential Travel Plan LAND SOUTH OF WOODFORD ROAD, BYFIELD, NORTHAMPTONSHIRE, NN11 6XD Residential Travel Plan Revision A Contents 1.0 Introduction 2.0 Policy and Guidance 3.0 Site Assessment 4.0 Proposed Development 5.0 Objectives and Targets 6.0 Travel Plan Measures 7.0 Management and Monitoring 8.0 Disclaimer Appendices A. Bus service 200 timetable B. Northamptonshire Bus Map Registration of Amendments Revision Revision Revision Amendment Details and Date Prepared By Approved By A Updated to include final layout and development details FB SS 21.07.17 Ref: FB/CC/P16-1149/01 Rev A Page 1 Land South of Woodford Road, Byfield, Northamptonshire, NN11 6XD Residential Travel Plan 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Create Consulting Engineers Ltd was instructed by Byfield Medical Centre to prepare a Travel Plan in support of the proposed development on land south of Woodford Road, Byfield, Northamptonshire. -

HS2 Newsletter Chipping Warden to Lower Boddington

Contact our HS2 Helpdesk team on 08081 434 434 HS2 Update Chipping Warden to Lower Boddington | July 2021 High Speed Two (HS2) is the new high speed railway for Britain. In response to COVID -19 we have worked hard to ensure that our working practices are fully aligned with the Site Operating Procedures produced by the Construction Leadership Council. These procedures have been endorsed by Public Health England. We will be keeping our local website www.hs2innorthants.co.uk up to date with information on our works in the local area. Update on our works Our activity in the Chipping Warden area is well underway. The storage areas, office and welfare accommodation at Chipping Warden compound are nearly finished. We have also cleared Join us online… vegetation and started earthworks on the Chipping Warden airfield. Over the summer our activity will increase in the Edgcote, Chipping Virtual one-to-one Warden and Lower Boddington areas and you can expect to see meetings - July 2021 the following works in the local area: We would like to invite • Utility works including trial holes; you to book an • Land surveys to measure land levels; appointment for a virtual • Ground Investigations (GI); one-to-one meeting with • Continued construction of the office accommodation and welfare our engagement team. facilities at Chipping Warden compound; They will be available to • The installation of a concrete batching plant; answer your questions • Further localised clearance of vegetation and fencing along the about the HS2 line of the route; programme and works in • Construction of access and haul roads to move people and your area. -

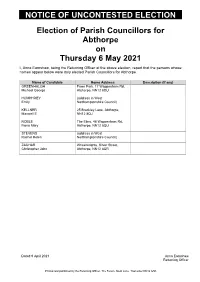

Notice of Uncontested Elections

NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Election of Parish Councillors for Abthorpe on Thursday 6 May 2021 I, Anna Earnshaw, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Abthorpe. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) GREENHALGH Fawe Park, 17 Wappenham Rd, Michael George Abthorpe, NN12 8QU HUMPHREY (address in West Emily Northamptonshire Council) KELLNER 25 Brackley Lane, Abthorpe, Maxwell E NN12 8QJ NOBLE The Elms, 48 Wappenham Rd, Fiona Mary Abthorpe, NN12 8QU STEVENS (address in West Rachel Helen Northamptonshire Council) ZACHAR Wheelwrights, Silver Street, Christopher John Abthorpe, NN12 8QR Dated 9 April 2021 Anna Earnshaw Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, The Forum, Moat Lane, Towcester NN12 6AD NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Election of Parish Councillors for Ashton on Thursday 6 May 2021 I, Anna Earnshaw, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Ashton. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) BULLOCK Old Manor Farm House, Roade Peter Charles Hill, Ashton, Northants, NN7 2JH DAY 8D Hartwell Road, Ashton, NN7 Bernard Ralph 2JR MCALLISTER (address in West Northants) Sarah Ann ROYCHOUDHURY `Wits End`, 8B Hartwell Road, Jeremy Sonjoy Ashton, Northamptonshire, NN7 2JR SHANAHAN (address in West Independent Neil Northamptonshire Council) Dated 9 April 2021 Anna Earnshaw Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, The Forum, Moat Lane, Towcester NN12 6AD NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Election of Parish Councillors for Aston Le Walls on Thursday 6 May 2021 I, Anna Earnshaw, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Aston Le Walls. -

In Parliament House of Commons Session 2013-14

1126 IN PARLIAMENT HOUSE OF COMMONS SESSION 2013-14 HIGH SPEED RAIL (LONDON - WEST MIDLANDS) BILL Against - on Merits - Praying to be heard By Counsel. &c. To the Honourable the Commons ofthe United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland in Parliament assembled. The humble Petition of Aston-le-Walls Parish Council SHEWETH as follow:- 1. A BiU (hereinafter referred to as "the BiU") has been introduced and is now pending in your honourable House intituled "A Bill to make provision for a railway between Euston in London and a junction with the West Coast Main Line at Handsacre in Staffordshire, with a spur from Old Oak Common in the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham to a junction with the Channel Tunnel Rail Link at York Way in the London Borough of Islington and a spur from Water Orton in Warwickshire to Curzon Street in Birmingham; and for connected purposes." 2. The Bill is presented by Mr. Secretary McLoughlin, supported by The Prime Minister, The Deputy Prime Minister, Mr. Chancellor of the Exchequer, Secretary Theresa May, Secretary Vince Cable, Secretary Iain Duncan Smith, Secretary Eric Pickles, Secretary Owen Paterson, Secretary Edward Davey, and Mr. Robert GoodwilL Clauses of the Bill 3. Clauses 1 to 36, together with Schedules 1-26 set out the BiU's objectives in relation to the construction and operation of the railway mentioned in paragraph 1 above. They include provision for the construction of works, highways and road traffic matters, the compulsory acquisition of land and other provisions relating to the use of land, planning permission, heritage issues, trees and noise. -

Public Session

PUBLIC SESSION MINUTES OF ORAL EVIDENCE taken before HIGH SPEED RAIL COMMITTEE On the HIGH SPEED RAIL (LONDON – WEST MIDLANDS) BILL Wednesday, 28 January (Afternoon) In Committee Room 5 PRESENT: Mr Robert Syms (Chair) Mr Henry Bellingham Sir Peter Bottomley Ian Mearns Mr Michael Thornton _____________ IN ATTENDANCE Mr Timothy Mould QC, Lead Counsel, Department for Transport Witnesses: Ms Joanna Wilson, Aston-le-Walls Parish Council Mr Maurice Cole, Thorpe Mandeville Parish Council Mr Ken Christy Ms Beryl Christy _____________ IN PUBLIC SESSION INDEX Subject Page Aston-le-Walls Parish Council Submissions from Ms Wilson 3 Submissions from Mr Mould 11 Thorpe Mandeville Parish Council Submissions from Mr Cole 18 Submissions from Mr Mould 26 Closing submissions from Mr Cole 29 Ken Christy and Beryl Christy Submissions from Mr Christy 31 Submission by Mr Mould 34 Closing submissions from Mr Christy 37 2 (at 14.00) 1. CHAIR: Welcome back this afternoon to the HS2 Select Committee. We hear this afternoon from Aston-le-Walls Parish Council and Joanna Wilson. Are you going to do an introduction, Mr Mould? 2. MR MOULD QC (DfT): I’m not going to introduce Ms Wilson’s petition. She’s going to deal with that. But can I just announce one thing, which I think will be of interest to the Committee and also to petitioners generally? It’s just to say that we have published a slightly revised version of information paper (E1), which is the information paper that explains the approach of the project to the control of environmental impacts, and it deals amongst other things with the environmental minimal requirements, which as you know have been a source of particular interest to petitioners. -

In Parliament House of Commons Session 2013-14

1521 IN PARLIAMENT HOUSE OF COMMONS SESSION 2013-14 HIGH SPEED RAIL (LONDON - WEST MIDLANDS) BILL Against - on Merits - [By Counsel], &c. To the Honourable the Commons of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland in Pariiament assembled. THE HUMBLE PETITION of: MR AND MRS DAVID FRUSHER SHEWETH as follows:- 1. A Bill (hereinafter referred to as "the Bill") has been introduced and is now pending in your Honourable House intituled "A Bill to make provision for a railway between Euston in London and a junction with the West Coast Main Line at Handsacre in Staffordshire, with a spur from Old Oak Common in the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham to a junction with the Channel Tunnel Rail Link at York Way in the London Borough of Islington and a spur from Water Orton in WanA/ickshire to Curzon Street in Birmingham; and for connected purposes." 2. The Bill is presented by Mr Secretary McLoughlin (referred to ih this Petition as the Promoter). 3. Clauses 1 to 3 of the Bill combined with Schedules 1 to 4 provide for that content relating to the proposed works in construction and maintenance including a schedule of the works and highway matters. 4. Clauses 4 to 18 of the Bill, along with Schedules 5 to 15 contain the prescriptions for compulsory acquisition, the temporary use of land for the duration and the access issues with creation or amendment of public rights of way. Compensation consideration is also deliberated within these Clauses. 5. Clauses 19 to 36 Of the Bill, and Schedules 16 to 26 make reference to the planning requirements and measures throughout the process, to include the deregulation of permanent site specific features. -

I Am Smarticus – BOBI Submission

Taking the fight to COVID-19 Understanding how the UK’s response to COVID-19 compares with that of other countries and why 1 Contents 1. Analytical approach and rationale 2. Executive Summary 3. How the UK measures up 4. The drivers of case and death rates internationally 5. The drivers of case and death rates in England 6. Gladiators, are you ready? 2 1. Analytical approach and rationale 3 In our analysis, we have answered the brief and have gone beyond it, in an engaging way An analysis of the global COVID-19 data, compared with and contrasted to the UK data • A good overview of the data, showing the key issues around the global pandemic The Brief • Commentary on the information • Tease out and answer questions that arise • Give the user the ability to interact with the data The key drivers/predicters of success in fighting the pandemic • Which countries did better and why? • How could we segment countries, based on their success in fighting We decided to go the pandemic beyond the brief • Which regions within England did better and why? 4 Before we started our analysis, we checked and filtered the world data for consistency 1. Countries removed 2. Consistent time period 3. Variables removed Non-country locations (e.g. continents) The majority of countries reported data We decided to concentrate on new cases were removed as it was not known how this from week 15 of 2020 (w/c 06/04/2020) and and new deaths as the most meaningful data was calculated. week 8 of 2021 (w/e 21/02/2021). -

A Railway Memorabilia Walk

WOW! W H A T ’ S O N I N W O O D F O R D ISSUE 150 July/Aug 2016 www.Woodford-Halse-VillageSignpost.co.uk twitter@woodfordVSP A Railway Memorabilia Walk July Events Short Mat Bowls Club This walk gives you a chance to see some of the remnants of the Meet each Monday (2-4pm) and Wednesday (7.30-9pm) in days when Woodford Halse was a major railway centre. the Dryden Hall. Contact Alan Williams for more information (Tel. 261824). The walk starts at “The Old Station Store” on Station Road (A). Here you can 5th Woodford and Hinton WI buy the late Jim Anscomb’s book “Woodford-cum-Membris and the Great On Tuesday 5 July we will be having a Bowls Evening. For details contact Diane Kenny on 01327 262454. Visitors Central Railway” (£6.50). always welcome. In this description of the walk I have given page references so that you can compare the 6th Woodford Halse Garden Club present with the heyday of the railway. On Wednesday 6 July we will be visiting Cramden Nurseries, If you look down Station Road, towards Hinton, where the old railway bridge crosses the Kingsthorpe. For details contact Coral Snow on 07486 road is where the station was. You can still see the blocked-up doorway behind which steps 388396. Pre-booking essential. Visitors £2.00. led up to the platforms. 10th Charity Cream Teas Come along and enjoy a cream tea or slice of cake in our Walk down Cherwell Terrace, past the rows of railway terraces. -

Greatworth to Lower Boddington HS2 London-West Midlands May 2013

PHASE ONE DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL STATEMENT Community Forum Area Report 15 | Greatworth to Lower Boddington HS2 London-West Midlands May 2013 ENGINE FOR GROWTH DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL STATEMENT Community Forum Area Report ENGINE FOR GROWTH 15 I Greatworth to Lower Boddington High Speed Two (HS2) Limited, 2nd Floor, Eland House, Bressenden Place, London SW1E 5DU Telephone 020 7944 4908 General email enquiries: [email protected] Website: www.hs2.org.uk © Crown copyright, 2013, except where otherwise stated Copyright in the typographical arrangement rests with the Crown. You may re-use this information (not including logos or third-party material) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or e-mail: [email protected]. Where we have identified any third-party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. To order further copies contact: DfT Publications Tel: 0300 123 1102 Web: www.dft.gov.uk/orderingpublications Product code: ES/26 Printed in Great Britain on paper containing at least 75% recycled fibre. CFA Report – Greatworth to Lower Boddington/No 15 I Contents Contents Draft Volume 2: Community Forum Area Report – Greatworth to Lower Boddington/No 15 5 Part A: Introduction 6 1 Introduction 7 1.1 Introduction to HS2 7 1.2 Purpose of this report 7 1.3 Structure of -

Countyconnect Welland Service 2 Countyconnect Daventry Service Countyconnect Brackley/ Towcester Service 3 Countyconnect Brackle

CountyConnect CountyConnect owlo free Rscaner myor ro er. r de i ov pr our y om r f r nne a c s QR e e r f a d oa wnl do Welland Service Daventry Service n a c ou y or r nne a c s t l nbui i n a e v ha s phone Rcoe dg irect e esite. o smrt t mar s t Mos . e t i webs he t o t t c e r di go nd a ode c QR 1 2 he t n a c s o t a mer a c phone t l nbui i our y e us n a c ou Y Arthingworth Hothorpe Adstone Ashley Husbands Bosworth Ashby St Ledgers Brampton Ash* (Leics)* Aston-le-Walls Braybrooke* Kelmarsh* Badby* Clipston Maidwell Brauston Cold Ashby Marston Trussell Brockhall Coton Middleton Cottesbrooke Naseby Canons Ashby Cottingham Sibbertoft Charwelton* Dingley* Stoke Albany* Church Stowe Draughton Sulby Cold Ashby East Carlton Sutton Bassett Cold Higham East Farndon Teeton Coton Thornby Crick* Guilsborough* Welford D * Harrington Weston-by-Welland Dodford Halselbech Wilbarston* East Haddon* Hollowell Everdon Elkington Served by a regular service Served by a regular service Bus Services 10 Daventry - Rugby Bus Services ia Middlemore, Barby, Kilsby and D 60 Northampton - Welford 11 Daventry - Long Buckby ia Hollowell, Guilsborough, Thornby and Naesby 1 Daventry - 67 Market Harborough - Corby 60 Northampton - Welford ia Sutton Bassett, Weston by Welland,Ashley, ia Hollowell, Guilsborough, Thornby and Naesby Dingley, StokeAlbany, East Carlton & Cottingham 65 Daventry - Leamington Spa ia St verton X7 Leicester - Market Harborough - Northampton 96 Rugby - Northampton Via Dirft, Crick, West Haddon, Watford, Long Buckby East Haddon 200 Daventry