Policy Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Green Space in Horfield and Lockleaze

Horfield Lockleaze_new_Covers 16/06/2010 13:58 Page 1 Horfield and Lockleaze Draft Area Green Space Plan Ideas and Options Paper Horfield and Lockleaze Area Green Space Plan A spatial and investment plan for the next 20 years Horfield Lockleaze_new_Covers 09/06/2010 11:29 Page 2 Horfield and Lockleaze Draft Area Green Space Plan If you would like this Vision for Green Space in informationBristol in a different format, for example, Braille, audio CD, large print, electronic disc, BSL Henbury & Southmead DVD or community Avonmouth & Kingsweston languages, please contact Horfield & Lockleaze us on 0117 922 3719 Henleaze, Westbury-on-Trym & Stoke Bishop Redland, Frome Vale, Cotham & Hillfields & Eastville Bishopston Ashley, Easton & Lawrence Hill St George East & West Cabot, Clifton & Clifton East Bedminster & Brislington Southville East & West Knowle, Filwood & Windmill Hill Hartcliffe, Hengrove & Stockwood Bishopsworth & Whitchurch Park N © Crown Copyright. All rights reserved. Bristol City Council. Licence No. 100023406 2008. 0 1km • raising quality • setting standards • providing variety • encouraging use • Horfield Lockleaze_new_text 09/06/2010 11:42 Page 1 Ideas and Options Paper Horfield and Lockleaze Area Green Space Plan Contents Vision for Green Space in Bristol Section Page Park Page Gainsborough Square Park 8 1. Introduction 2 A city with good quality, Monks Park 9 2. Background 3 Horfield Common, including the Ardagh 10-11 attractive, enjoyable and Blake Road Open Space and 12 Rowlandson Gardens Open Space accessible green spaces which 3. Investment ideas and options to 7 Bonnington Walk Playing Fields 13 improve each open space within the area meet the diverse needs of all Dorian Road Playing Fields 14 4. -

Bristol Local Plan Review: Policies and Site Allocations Proposed to Be

Bristol Local Plan Review: Policies and site allocations proposed to be retained The following Bristol Local Plan policies and site allocations were proposed to be retained in the Bristol Local Plan Review consultation (March 2019). Core Strategy (July 2011) Policies • BCS7: Centres and retailing • BCS9: Green Infrastructure • BCS12: Community facilities • BCS16: Flood risk and water management • BCS21: Quality urban design • BCS22: Conservation and the historic environment Site Allocations and Development Management Policies (June 2014) Community Facilities policies • DM5: Protection of Community Facilities • DM6: Public Houses Centres and Retailing policies • DM7: Town Centre Uses • DM8: Shopping areas and frontages • DM9: Local centres • DM10: Food and drink uses and the evening economy • DM11: Markets Health policies • DM14: The Health Impacts of Development Green Infrastructure policies • DM15: Green Infrastructure Provision • DM16: Open Space for Recreation Bristol Local Plan Review: Policies and site allocations proposed to be retained • DM17: Development involving existing green infrastructure (Trees and Urban Landscape) • DM19: Development and Nature Conservation • DM20: Regionally Important Geological Sites • DM21: Private Gardens • DM22: Development Adjacent to Waterways Transport and Movement policies • DM23: Transport Development Management • DM25: Greenways Design and Conservation policies • DM27: Layout and form • DM28: Public Realm • DM29: Design of New Buildings • DM30: Alterations to Existing Buildings • DM31: Heritage -

Green Space in Ashley, Easton and Lawrence Hill

Ashley Easton Lawrence Hill AGSP_new_Covers 09/06/2010 11:24 Page 1 Ideas and Options Paper Ashley, Easton and Lawrence Hill Area Green Space Plan Ideas and Options Paper Ashley, Easton and Lawrence Hill Area Green Space Plan A spatial and investment plan for the next 20 years • raising quality • setting standards • providing variety • encouraging use • 1 Ashley Easton Lawrence Hill AGSP_new_Covers 09/06/2010 11:24 Page 2 Ideas and Options Paper Ashley, Easton and Lawrence Hill Area Green Space Plan If you would like this Vision for Green Space in informationBristol in a different format, for example, Braille, audio CD, large print, electronic disc, BSL Henbury & Southmead DVD or community Avonmouth & Kingsweston languages, please contact Horfield & Lockleaze us on 0117 922 3719 Henleaze, Westbury-on-Trym & Stoke Bishop Redland, Frome Vale, Cotham & Hillfields & Eastville Bishopston Ashley, Easton & Lawrence Hill St George East & West Cabot, Clifton & Clifton East Bedminster & Brislington Southville East & West Knowle, Filwood & Windmill Hill Hartcliffe, Hengrove & Stockwood Bishopsworth & Whitchurch Park N © Crown Copyright. All rights reserved. Bristol City Council. Licence No. 100023406 2008. 0 1km • raising quality • setting standards • providing variety • encouraging use • Ashley Easton Lawrence Hill AGSP_new_text 09/06/2010 11:18 Page 1 Ideas and Options Paper Ashley, Easton and Lawrence Hill Area Green Space Plan Contents Vision for Green Space in Bristol Section Page Park Page A city with good quality, 1. Introduction 2 Riverside Park and Peel Street Green Space 9 Rawnsley Park 10-12 attractive, enjoyable and 2. Background 3 Mina Road Park 13 accessible green spaces which Hassell Drive Open Space 14-15 meet the diverse needs of all 3. -

Professor Philip Alston United Nations Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and Human Rights

Professor Philip Alston United Nations Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and Human Rights By email Our Ref: ZA37220 7 November 2018 Dear Professor Alston I am writing regarding your inquiry into poverty in the United Kingdom and in particular the challenges facing so-called peripheral estates in large cities. This week you have been in Bristol, one of the wealthiest cites in the United Kingdom and the only one of the ten Core Cities which is a net contributor to the UK Treasury. However, Bristol is also an unequal city and I am convinced that the actions of central government since 2010 have made this worse. The constituency which I am proud to represent, Bristol South, has the highest number of social security claimants in the city, the poorest health outcomes and the lowest educational attainment. The southern part of my constituency also suffers from extremely poor transport links to the rest of the city and higher crime than most areas. Thousands of people depend on national or local government for financial and other support, support which has been dramatically reduced since 2010. They have been hit disproportionately by the austerity imposed by the Conservative/Liberal Democrat coalition government 2010-15 and the Conservative government since 2015. The electoral ward of Hartcliffe and Withywood is the most south-eastern part of the city where it meets the countryside of North Somerset. It contains five of the ten most deprived communities in Bristol as defined by the Bristol City Council Local Super Output Area (LSOAs) Indices of Multiple Deprivation 2015. Nearby Filwood ward has a further three of these ten most deprived LSOAs. -

515 Bus Service Valid from January 2019

.travelwest.info www BD11449 DesignedandprintedonsustainablysourcedmaterialbyBristolDesign,CityCouncil–January2019 on 0117 922 2910 922 0117 on CD-ROM or plain text please contact Bristol City Council Council City Bristol contact please text plain or CD-ROM Braille, audio tape, large print, easy English, BSL video, video, BSL English, easy print, large tape, audio Braille, If you would like this information in another language, language, another in information this like would you If Hartcliffe – Imperial Park Imperial – Hartcliffe Whitchurch – Hengrove Park – Park Hengrove – Whitchurch Stockwood – Hengrove – Hengrove – Stockwood Valid from January 2019 January from Valid Bus Service Bus 515 www.travelwest.info/bus other bus services in Bristol is available at: available is Bristol in services bus other Timetable, route and fares information for service 515 and and 515 service for information fares and route Timetable, Produced by Sustainable Transport. Sustainable by Produced www.bristolcommunitytransport.org.uk w: [email protected] e: contract by Bristol Community Transport. Community Bristol by contract 0117 941 3713 941 0117 t: under operated is and Council City Bristol please contact Bristol Community Transport: Community Bristol contact please Service 515 is financially supported by by supported financially is 515 Service enquiries property lost and information fares For 0 37 A SS PA holidays. public [email protected] Y e: B N O ST except Saturday to Monday operates service The A 2910 922 0117 t: G N LO Information -

Agenda Item No. 3 Filwood, Knowle and Windmill Hill

AGENDA ITEM NO. 3 FILWOOD, KNOWLE AND WINDMILL HILL NEIGHBOURHOOD PARTNERSHIP 6.00 PM ON 13TH MARCH 2012 AT KNOWLE WEST MEDIA CENTRE, LEINSTER AVENUE, FILWOOD, BRISTOL BS4 1NL PRESENT: Ward Councillors: Councillor Chris Jackson and Jeff Lovell Filwood Ward Councillor Gary Hopkins and Christopher Davies Knowle Ward Councillor Mark Bailey and Alf Havvock Windmill Hill Ward Other members of the Partnership: Les Bowen Resident Denise Britt Resident Nancy Carlton Resident Ken Jones Resident Ann Smith Resident Judith Brown Equalities Rep Inspector Colin Salmon Avon & Somerset Police Also Present: Helen Adshed Windmill Hill Resident Helen Bone Windmill Hill Resident G. I Brown Windmill Hill BOPF Karen Blong Democratic Services Naomi Button Hengrove Park Leisure Centre James Dowling BCC Highways Iris Eiting Filwood Resident Richard Fletcher Environment and Leisure, BCC Kurt James Area Coordinator, Bristol City Council Ian Onions Evening Post Paul Owens KWRF Programme Manager, BCC Bob Slader Knowle Resident Andy Tyas Major Projects Team Manager, BCC APOLOGIES: Suzanne Audrey Windmill Hill Resident Lee Reed Equalities Representative John Scott Resident Item No: 1. WELCOME AND INTRODUCTIONS The Chair, Councillor Christopher Jackson welcomed everyone to the meeting and introductions were made. The Chair requested a change to the agenda in order to accommodate the public speaker which the Neighbourhood Partnership Agreed. 2. DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST There were no declarations of interest. 3. PUBLIC FORUM AND REQUESTS FOR LOCAL ACTION a) Eldon Terrance Bike Locker Proposal Helen Adshead, a resident of Eldon Terrace presented information related to a bike locker proposal and highlighted the current problems for bike storage in the area. -

The Impacts of Mayoral Governance in Bristol

The Bristol Civic Leadership Project The Impacts of Mayoral Governance in Bristol Robin Hambleton and David Sweeting September 2015 The Bristol Civic Leadership Project The Impacts of Mayoral Governance in Bristol Robin Hambleton and David Sweeting September 2015 Contents List of tables 4 List of figures 5 Executive summary 6 1 Introduction: what this report is about 8 2 Context: the debate about directly elected mayors in the UK 11 3 The Bristol Civic Leadership Project 15 4 Leadership in the community 21 5 Effective representation of the citizen 26 6 Legitimacy and accountability 31 7 Effectiveness in decision-making and implementation 34 8 Effective scrutiny of policy and performance 39 9 Responsiveness to local people 43 10 Strategic choices for urban governance in Bristol in 2025 45 Notes 50 Appendix 1: Survey research methods 51 Appendix 2: Socio-economic geography of Bristol 54 Appendix 3: Citizens’ Panel survey, 2012 and 2014, percent agree, by 56 ward socio-economic category Appendix 4: Civic Leaders’ survey, 2012 and 2014, percent agree, by 59 realm of leadership About the authors 61 Acknowledgements 62 3 List of tables 1 Bristol wards by socio-economic category 17 2 Citizens’ Panel survey, 2012 and 2014, leadership in the community, 21 percent agree 3 Civic Leaders’ survey, 2012 and 2014, leadership in the community, 23 percent agree 4 Citizens’ Panel survey, 2012 and 2014, effective representation of the 26 citizen, percent agree 5 Civic Leaders’ survey, 2012 and 2014, effective representation of the 28 citizen, percent agree, -

ID Description Cost (000) 15/16 16/17 17/18 SOUTH S1 Filwood Quietway

ID Description Cost (000) 15/16 16/17 17/18 SOUTH S1 Filwood Quietway Creating a direct and convenient route from Filwood Green and Hengrove development areas to the Brunel Mile and the Enterprise Zone. To include a new bridge 2,300 250 250 1,800 from Clarence Rd to Whitehouse St and a route to Victoria Park (linking with Malago Quietway) to Filwood. Route to be determined with local communities, but significantly improving access to Northern Slopes for all path users. S2 Malago Quietway Upgrade to create a more direct and convenient route from Whitchurch Way to Victoria Park to link with the new Filwood Quietway. Improvements along the 600 250 250 100 Malago and at crossings. Improved path through Victoria Park, linking to the new Filwood Quietway. S3 Family Cycling Centre Capital works attached to the Filwood / Hengrove family cycling centre to offer bikeability to children, parents and carers. Including specially adapted cycles. 250 250 NORTH N1 Southmead Quietway Quiet streets, and on road routes to create a legible route between 'the Arches' and Southmead Hospital with investigation into improving the A38 south to the city 100 100 centre as part of a corridor approach. N2 Frome Quietway Segregated traffic free route along Blackberry Hill to complete this key route. Supporting new housing and employment developments in the area with the North 800 400 400 Fringe. N3 Safer Street Spaces' Create a Bristol 'template' for neighbourhoods with pilot area in Easton. Light touch traffic calming and surface treatments, decluttering, build outs and planting to 200 50 50 100 reduced speeds and through traffic. -

Portishead Branch Line (Metrowest Phase 1)

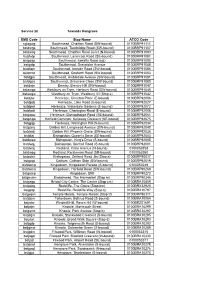

Portishead Branch Line (MetroWest Phase 1) TR040011 Applicant: North Somerset District Council 6.25, Environmental Statement, Volume 4, Technical Appendices, Appendix 16.1: Transport Assessment (Part 6 of 18) – Appendix B, Committed Developments The Infrastructure Planning (Applications: Prescribed Forms and Procedure) Regulations 2009, Regulation 5(2)(a) Planning Act 2008 Author: CH2M Date: November 2019 PORTISHEAD BRANCH LINE DCO SCHEME (METROWEST PHASE 1) ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT Transport Assessment Appendix B List of Committed Developments Prepared for West of England Councils June 2018 1 The Square Temple Quay Bristol BS1 6DG Document History Portishead Branch Line DCO Scheme (MetroWest Phase 1) Transport Assessment Appendix B: List of Committed Developments Reference Number: 674946.CS.70.01/TA Client Name: West of England Councils This document has been issued and amended as follows: Version Date Description Created by Verified by Approved by 01 February 2016 Draft JE HS HS 02 June 2018 Final JE HS HS UA Ref Area Further Detail BCC O10_877 Former Courage Brewery Counterslip Redcliff Bristol BCC O10_1067 Former Imperial Tobacco Office Building Hengrove Way Bristol BS14 0HR BCC O10_878A Part 2 ND10 The Zone Anvil Street Bristol BS2 0LT BCC O10_565 Land Bounded By Redcliff Street, St Thomas Street And Three Queens Lane, Redcliffe Bristol BCC O10_1159 Pring & St Hill Ltd Malago Road Bristol BS3 4JH BCC O10_1206 80 Stokes Croft Bristol BS1 3QY BCC O10_1235 Ashton Vale And Former Alderman Moore Allotments Off Ashton Road (B3128) Bristol BCC O10_1243 Paintworks Bristol BS4 3EH BCC O10_1245 Sainsburys Winterstoke Road Bristol BS3 2NS BCC O10_1029 Former Post Office Sorting Depot Cattle Market Road Bristol BS1 1BX BCC O10_878E Plot ND9 Temple Quay 2 Avon Street Bristol BCC O10_541 Huller House/South Warehouse, Redcliff Backs. -

Bristol City Council Portfolio Location Ward Tree Species Planted 2012

Bristol City Council Portfolio Location Ward Tree Species Planted 2012-13 Highways -South A37 Stockwood Ulmus 'New Horizon' Highways -South A37 Stockwood Ulmus 'New Horizon' Highways -South A37 Stockwood Ulmus 'New Horizon' Highways -South A37 Stockwood Ulmus 'New Horizon' Highways -South A37 Stockwood Ulmus 'New Horizon' Highways -South A37 Stockwood Ulmus 'New Horizon' Highways -South A37 Stockwood Ulmus 'New Horizon' Highways -South A37 Stockwood Ulmus 'New Horizon' Highways -South A37 Stockwood Ulmus 'New Horizon' Highways -South A37 Stockwood Ulmus 'New Horizon' Highways -South A37 Stockwood Ulmus 'New Horizon' Highways -South A37 Stockwood Ulmus 'New Horizon' Highways -South A37 Stockwood Ulmus 'New Horizon' Highways -South A37 Stockwood Ulmus 'New Horizon' Highways -South A37 Stockwood Ulmus 'New Horizon' Highways -South A37 Stockwood Ulmus 'New Horizon' Highways -South A37 Stockwood Ulmus 'New Horizon' Highways -South A37 Stockwood Ulmus 'New Horizon' Highways -South A37 Stockwood Ulmus 'New Horizon' Highways -South A37 Stockwood Ulmus 'New Horizon' Highways -South A37 Stockwood Ulmus 'New Horizon' Highways -South A37 Stockwood Ulmus 'New Horizon' Highways -South A37 Stockwood Ulmus 'New Horizon' Highways -South A37 Stockwood Ulmus 'New Horizon' Highways -South A37 Stockwood Ulmus 'New Horizon' Highways -South A37 Stockwood Ulmus 'New Horizon' Highways -South A37 Stockwood Ulmus 'New Horizon' Highways -South A37 Stockwood Ulmus 'New Horizon' Highways -South A37 Stockwood Ulmus 'New Horizon' Highways -South A37 Stockwood Ulmus -

Step 1: What Is the Proposal? Please Explain Your Proposal in Plain English, Avoiding Acronyms and Jargon

Bristol City Council Equality Impact Assessment Form – St Werburgh’s Primary School Input (Please refer to the Equality Impact Assessment guidance when completing this form) Name of proposal Draft Model Risk Assessment for Schools Re- Opening after Covid-19 Closure Directorate and Service Area People , Education Services Name of Lead Officer Christina Czarkowski Crouch Step 1: What is the proposal? Please explain your proposal in Plain English, avoiding acronyms and jargon. This section should explain how the proposal will impact service users, staff and/or the wider community. 1.1 What is the proposal? The model risk assessment for School Re-Opening, has been prepared to assist Schools negotiate the various Public Health England guidance in relation to the risks associated with the COVID 19 virus. The assessment has been prepared to help Schools instigate suitable control measures to help protect the School’s Staff / Pupils and Visitors. The risk assessment has been fully completed for the planned wider opening of St Werburgh’s Primary School to children in Reception, Year 1 and Year 6. The proposal is to open for small groups of pupils in Reception, Year 1 and Year 6 initially on a part time basis form Monday 8th June if the government and Bristol City Council advise that it is safe for us to do so. This will ensure that children can be in a familiar setting with familiar staff and come back into school in a phased way. Each group of children will operate as a ‘bubble’ which will not come into contact with or interact with other ‘bubbles’ of children. -

SMS Codes Are Different in Each Direction

Service 20 Towards Hengrove SMS Code Stop Name ATCO Code sglagwg Southmead, Charlton Road (SW-bound) 0170BRP91111 bstdwgp Southmead, Turnbridge Road (SW-bound) 0100BRP91107 bstdwag Southmead, Charlton Road Junct (N-bound) 0100BRP91093 bstdwtp Southmead, Lanercost Road (SE-bound) 0100BRP91091 bstgdap Southmead, Jarratts Road (adj) 0100BRP91090 bstgatp Southmead, Greystoke Avenue 0100BRP91088 bstdtam Southmead, Arnside Road (SW-bound) 0100BRP91086 bstdmtd Southmead, Gosforth Road (SW-bound) 0100BRP91083 bstdjpa Southmead, Ambleside Avenue (SW-bound) 0100BRP91081 bstdgpa Southmead, Grasmere Close (SW-bound) 0100BRP91080 bstdaja Brentry, Brentry Hill (SW-bound) 0100BRP91047 bstawgp Westbury on Trym, Henbury Road (SW-bound) 0100BRP91045 bstawgw Westbury on Trym, Westbury Vil (Stop e) 0100BRP91042 bstdjtw Henleaze, Cheriton Place (E-bound) 0100BRP92006 bstdpdj Henleaze, Lake Road (E-bound) 0100BRP92027 bstdpwt Henleaze, Waterdale Gardens (E-bound) 0100BRP92072 bstdwdt Henleaze, Cherington Road (E-bound) 0100BRP92008 bstgapw Henleaze, Bishopthorpe Road (SE-bound) 0100BRP92061 bstgmga Horfield Common, Kellaway Crescent (SE-bound) 0100BRP92075 bstgpjg Henleaze, Wellington Hill (N-bound) 0100BRP92034 bstgamj Golden Hill, Longmead Avenue (SW-bound) 0100BRP92040 bstdwdj Golden Hill, Phoenix Grove (SW-bound) 0100BRP92036 bstdtaj Bishopston, Queen’s Drive (SE-bound) 0100BRP92003 bstdwaw Bishopston, King’s Drive (S-bound) 0100BRP92005 bstdwgj Bishopston, Birchall Road (S-bound) 0100BRP92001 bstdwaj Redland, Clare Avenue (N-bound) 0100053258 bstdwpg Redland,