Crisis Study Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baltic Towns030306

Seventeenth Century Baltic Merchants is one of the most frequented waters in the world - if not the Tmost frequented – and has been so for the last thousand years. Shipping and trade routes over the Baltic Sea have a long tradition. During the Middle Ages the Hanseatic League dominated trade in the Baltic region. When the German Hansa definitely lost its position in the sixteenth century, other actors started struggling for the control of the Baltic Sea and, above all, its port towns. Among those coun- tries were, for example, Russia, Poland, Denmark and Sweden. Since Finland was a part of the Swedish realm, ”the eastern half of the realm”, Sweden held positions on both the east and west coasts. From 1561, when the town of Reval and adjacent areas sought protection under the Swedish Crown, ex- pansion began along the southeastern and southern coasts of the Baltic. By the end of the Thirty Years War in 1648, Sweden had gained control and was the dom- inating great power of the Baltic Sea region. When the Danish areas in the south- ern part of the Scandinavian Peninsula were taken in 1660, Sweden’s policies were fulfilled. Until the fall of Sweden’s Great Power status in 1718, the realm kept, if not the objective ”Dominium Maris Baltici” so at least ”Mare Clausum”. 1 The strong military and political position did not, however, correspond with an economic dominance. Michael Roberts has declared that Sweden’s control of the Baltic after 1681 was ultimately dependent on the good will of the maritime powers, whose interests Sweden could not afford to ignore.2 In financing the wars, the Swedish government frequently used loans from Dutch and German merchants.3 Moreover, the strong expansion of the Swedish mining industries 1 Rystad, Göran: Dominium Maris Baltici – dröm och verklighet /Mare nostrum. -

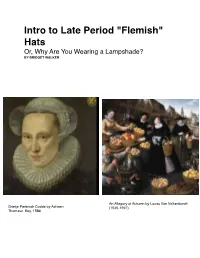

"Flemish" Hats Or, Why Are You Wearing a Lampshade? by BRIDGET WALKER

Intro to Late Period "Flemish" Hats Or, Why Are You Wearing a Lampshade? BY BRIDGET WALKER An Allegory of Autumn by Lucas Van Valkenborch Grietje Pietersdr Codde by Adriaen (1535-1597) Thomasz. Key, 1586 Where Are We Again? This is the coast of modern day Belgium and The Netherlands, with the east coast of England included for scale. According to Fynes Moryson, an Englishman traveling through the area in the 1590s, the cities of Bruges and Ghent are in Flanders, the city of Antwerp belongs to the Dutchy of the Brabant, and the city of Amsterdam is in South Holland. However, he explains, Ghent and Bruges were the major trading centers in the early 1500s. Consequently, foreigners often refer to the entire area as "Flemish". Antwerp is approximately fifty miles from Bruges and a hundred miles from Amsterdam. Hairstyles The Cook by PieterAertsen, 1559 Market Scene by Pieter Aertsen Upper class women rarely have their portraits painted without their headdresses. Luckily, Antwerp's many genre paintings can give us a clue. The hair is put up in what is most likely a form of hair taping. In the example on the left, the braids might be simply wrapped around the head. However, the woman on the right has her braids too far back for that. They must be sewn or pinned on. The hair at the front is occasionally padded in rolls out over the temples, but is much more likely to remain close to the head. At the end of the 1600s, when the French and English often dressed the hair over the forehead, the ladies of the Netherlands continued to pull their hair back smoothly. -

On the Regulatory Function and Historical Significance of the Peace of Augsburg (1555) in Religious Conflicts

Cultural and Religious Studies, October 2019, Vol. 7, No. 10, 571-585 doi: 10.17265/2328-2177/2019.10.003 D DAVID PUBLISHING On the Regulatory Function and Historical Significance of the Peace of Augsburg (1555) in Religious Conflicts WANG Yinhong China University of Political Science and Law, Beijing, China In 1555, the Imperial Diet in Augsburg passed a resolution to extend the application of decrees concerning peace and order of the Holy Roman Empire to religious issues, trying to achieve religious peace and order of the Empire. The Peace of Augsburg (1555) explicitly recognizes the legal existence of Lutheranism and stipulates the “religious freedom” of Imperial Estates, “cuius regio, eius religio” principle, and its exceptions. However, due to the lack of effective mechanism and measures to guarantee the compliance with the Peace of Augsburg (1555), its regulatory function can only be realized through “commitment”. The Peace of Augsburg (1555) is mainly formulated to pursue the peace and order of the Empire and also reflects the fundamental principle of compromise. However, the concepts such as “religious tolerance” and “right protection” contained therein are not original intention of the Peace of Augsburg (1555) or the subjective wishes of all parties thereto. Keywords: Holy Roman Empire, Imperial Diet in Augsburg, the Peace of Augsburg (1555), “cuius regio, eius religio” principle On October 31, 1517, Martin Luther published his Disputatio Pro Declaratione Virtutis Indulgentiarum (Disputation on the Power of Indulgences in English, also known as the Ninety-Five Theses) at the Schlosskirche in Wittenberg, which was spread to the most German areas of Holy Roman Empire in a short time-frame and became the prelude to the Reformation in German areas. -

The Czechs and the Lands of the Bohemian Crown

6 Rebellion and Catastrophe The Thirty Years’ War was the last great religious war in Europe, and the first Europe-wide conflict of balance-of-power politics. Beginning with the Bohemian rebellion in 1618, the war grew into a confrontation between the German Protestant princes and the Holy Roman Emperor, and finally became a contest between France and the Habsburgs’ two dynastic monarchies, involving practically all other powers. The war may be divided into four phases: the Bohemian-Palatinate War (1618– 23), the Danish War (1625–29), the Swedish War (1630–35), and the Franco-Swedish War (1635–48). When the war finally ended with the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, the treaties set the groundwork for the system of international relations still in effect today. The outcome of the war integrated the Bohemian crownlands more fully with the other Habsburg possessions in a family empire that aspired to maintain its position as one of the powers in the international state system. This aspiration involved recurrent conflicts, on one side with the Turks, and on the other with Louis XIV’s France. .......................... 10888$ $CH6 08-05-04 15:18:33 PS PAGE 68 Rebellion and Catastrophe 69 VAE VICTIS!: THE BOHEMIAN CROWNLANDS IN THE THIRTY YEARS’ WAR After the Battle of the White Mountain and Frederick’s flight from Prague (his brief reign earned him the epithet ‘‘The Winter King’’), the last garrisons loyal to the Estates in southern and western Bohemia surrendered in May 1622. Even before these victories Ferdinand II began to settle accounts with his Bohemian opponents. -

SCS News Fall 2004, Volume 3, Number 1

Swedish Colonial News Volume 3, Number 1 Fall 2004 Preserving the legacy of the New Sweden Colony in America The Faces of New Sweden now in print Kim-Eric Williams After more than two years of work, the long-awaited The Faces of New Sweden is now available and was premiered at the New Sweden History Conference on November 20 in Wilmington, DE. It is a perfect-bound book and includes many full color reproductions of the recently rediscovered paintings of Pastor Erik Björk and his wife Christina Stalcop. Erik Björk was one of the three Church of Sweden priests sent to America in 1697 by Jesper Svedberg and King Carl IX to revive the churches and serve the remaining Swedes on the Delaware. He was pastor at Holy Trinity (Old Swedes’) Church in Wilmington from 1697 until 1713. The portraits of Björk and his wife seem to date to 1712 and are by America’s first portrait painter, Gustavus (Gustaf) Hesselius, who was the brother of the next two Swedish priests to serve in Wilmington, Andreas Hesselius and Samuel Hesselius. The family background of the painter Gustavus Hesselius and the families of Erik Björk and Christina Stalcop is told by the author Hans Ling of Uppsala, Sweden, legal advisor to the National Heritage Board and a Forefather member of the Swedish Colonial Society. In this Issue... continued on page 6 HISTORIC SITE OBSERVATIONS Delaware National Printzhof Bricks 5 Coastal Heritage 16 FOREFATHERS Park DELEGATION 2 Pål Jönsson Mullica 7 to Sweden 2004 FOREFATHERS Dr. Peter S. Craig this land was surveyed and patented. -

A History of Oysters in Maine (1600S-1970S) Randy Lackovic University of Maine, [email protected]

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Darling Marine Center Historical Documents Darling Marine Center Historical Collections 3-2019 A History of Oysters in Maine (1600s-1970s) Randy Lackovic University of Maine, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/dmc_documents Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, and the United States History Commons Repository Citation Lackovic, Randy, "A History of Oysters in Maine (1600s-1970s)" (2019). Darling Marine Center Historical Documents. 22. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/dmc_documents/22 This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Darling Marine Center Historical Documents by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A History of Oysters in Maine (1600s-1970s) This is a history of oyster abundance in Maine, and the subsequent decline of oyster abundance. It is a history of oystering, oyster fisheries, and oyster commerce in Maine. It is a history of the transplanting of oysters to Maine, and experiments with oysters in Maine, and of oyster culture in Maine. This history takes place from the 1600s to the 1970s. 17th Century {}{}{}{} In early days, oysters were to be found in lavish abundance along all the Atlantic coast, though Ingersoll says it was at least a small number of oysters on the Gulf of Maine coast.86, 87 Champlain wrote that in 1604, "All the harbors, bays, and coasts from Chouacoet (Saco) are filled with every variety of fish. -

Civ V Civiliza Tion Over View

Unique Unit Unique U/B/I Civ Leader (Replaces) (Replaces/Improves) Special Ability Minuteman B-17 America Washington (Musketman) (Bomber) Manifest Destiny: All land military units have +1 sight range. 50% discount when purchasing tiles. Camel Archer Bazaar Arabia Harun al-Rashid Trade Caravans: Caravans have 50% greater range and Arabia spreads religion along trade routes at double the (Knight) (Market) normal rate. Siege Tower Royal Library Assyria Ashurbanipal (Catapult) (Library) Treasures of Nineveh: Steal an enemy technology when taking a city. Can be used only once per city. Hussar Coffee House Austria Maria Theresa (Cavalry) (Windmill) Diplomatic Marriage: Can spend Gold to annex or puppet an allied City-State. Jaguar Floating Gardens Aztecs Montezuma (Warrior) (Water Mill) Sacrificial Captives: Gain Culture for the empire from each enemy unit killed. Bowman Walls of Babylon Babylon Nebuchadnezzar II Ingenuity: Receive a free Great Scientist when you discover Writing. Earn Great Scientists at double the normal (Archer) (Walls) rate. Pracinhas Brazilwood Camp Brazil Pedro II (WWII Infantry) (Improves Jungle) Carnival: Tourism output doubled and spawn rate of Great Artists (all types) increased during Golden Ages. Cataphract Dromon Byzantium Theodora (Horseman) (Tireme) Patriarchate of Constantinople: Choose one more Belief than normal when you found a Religion. Forest Elephant Quinquereme Carthage Dido Phoenician Heritage: All coastal Cities get a free Harbor. Units may cross mountains after the first Great General is (Horseman) (Tireme) earned, taking 50 HP damage if they end a turn on a mountain. Pictish Warrior Ceilidh Hall Celts Boudicca Druidic Lore: +1 Faith per city with an adjacent unimproved Forest. Bonus increases to +2 Faith in Cities with 3 (Spearman) (Opera House) more more adjacent unimproved Forest tiles. -

Soldiering and the Making of Finnish Manhood

Soldiering and the Making of Finnish Manhood Conscription and Masculinity in Interwar Finland, 1918–1939 ANDERS AHLBÄCK Doctoral Thesis in General History ÅBO AKADEMI UNIVERSITY 2010 © Anders Ahlbäck Author’s address: History Dept. of Åbo Akademi University Fabriksgatan 2 FIN-20500 Åbo Finland e-mail: [email protected] ISBN 978-952-12-2508-6 (paperback) ISBN 978-952-12-2509-3 (pdf) Printed by Uniprint, Turku Table of Contents Acknowledgements v 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Images and experiences of conscripted soldiering 1 1.2 Topics in earlier research: The militarisation of modern masculinity 8 1.3 Theory and method: Conscription as a contested arena of masculinity 26 1.4 Demarcation: Soldiering and citizenship as homosocial enactments 39 2 The politics of conscription 48 2.1 Military debate on the verge of a revolution 52 2.2 The Civil War and the creation of the “White Army” 62 2.3 The militiaman challenging the cadre army soldier 72 2.4 From public indignation to closing ranks around the army 87 2.5 Conclusion: Reluctant militarisation 96 3 War heroes as war teachers 100 3.1 The narrative construction of the Jägers as war heroes 102 3.2 Absent women and distant domesticity 116 3.3 Heroic officers and their counter-images 118 3.4 Forgetfulness in the hero myth 124 3.5 The Jäger officers as military educators 127 3.6 Conclusion: The uses of war heroes 139 4 Educating the citizen-soldier 146 4.1 Civic education and the Suomen Sotilas magazine 147 4.2 The man-soldier-citizen amalgamation 154 4.3 History, forefathers and the spirit of sacrifice -

Female Education in the Late Sixteenth and Early Seventeenth Centuries in England and Wales: a Study of Attitudes and Practi Ce

FEMALE EDUCATION IN THE LATE SIXTEENTH AND EARLY SEVENTEENTH CENTURIES IN ENGLAND AND WALES: A STUDY OF ATTITUDES AND PRACTI CE Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy: January 1996 Caroline Mary Kynaston Bowden Institute of Education, University of London \ 2 ABSTRACT OF THESIS This thesis provides a study of attitudes and practice in respect of female education in England and Wales in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. It begins with a review of primary and secondary sources, and throughout draws substantially upon personal documents consulted in collections of family papers covering a wide geographical area. These documents, it is argued are broadly representative of gentry families. Chapter Two examines the education of daughters; Chapter Three the role of women in marriage; Chapter Four motherhood. Each of these chapters examines the links between education and the roles girls and women fulfilled. Throughout these three chapters, contrasts and comparisons are drawn between prescriptive advice and practice. Chapter Five considers the difficult issue of standards in the education of girls and women, while the final chapter examines some of the outcomes of education in terms of women as intermediaries in informal power networks, estate and farm managers and educational benefactors and founders. The thesis draws conclusions in respect of the importance of education in permitting the developing role of women in both private and public spheres and examines the reasons for such changes. It also challenges existing theories regarding the differences between Catholic and Protestant attitudes to girls' education. A substantial appendix listing some 870 educated and literate women of the period is provided, both to demonstrate the major sources for this study and to provide a basis for future research. -

Germany (1914)

THE MAKING OF THE NATIONS GERMANY VOLUMES ALREADY PUBLISHED IN THIS SERIES FRANCE By Cecil Headlam, m.a. COXTAIXING 32 FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS AND 16 MAPS AND SMALLER FIGURES IN THE TEXT " It is a sound and readable sketch, which has the signal merit of keeping^ what is salient to the front." British Weekly. SCOTLAND By Prof. Robert S. Rait CONTAINING 32 FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS AND 11 MAPS AND SMALLER FIGURES IN THE TEXT of "His 'Scotland' is an equally careful piece work, sound in historical fact, critical and dispassionate, and dealing, for the most part, with just those periods in which it is possible to trace a real advance in the national develop- ment."—Athenceum. SOUTH AMERICA By W. H. KoEBEL CONTAINING 32 FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS AND 10 MAPS AND SMALLER FIGURES IN THE TEXT " Mr. Koebel has done his work well, and by laying stress on the trend of Governments and peoples rather than on lists of Governors or Presidents, and by knowing generally what to omit, he has contrived to produce a book which meets an obvious need. ' —Morning Post. A. AND C. BLACK, 4 SOHO SQUARE, LONDON, W. AGENTS AMERICA .... THE MACMILLAN COMPANY 64 & 66 FIFTH AVENUE. NEW YORK AUSTEALA8IA . OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS 20- FLINDERS Lane. MELBOURNE CANADA THE MACMILLAN COMPANY OF CANADA. LTD. St. Marti.n's House, 70 Bond street, TORONTO RiDLA MACMILLAN 4 COMPANY, LTD. MACMILLAN BUILDING, BOMBAY 309 Bow Bazaar STREBT, CALCUTTA ^. Rischgits QUEEN LOUISE (lT7G-lS10), WinOW OF FREDERICK -WILLIAM III. OF PRUSSIA. Her patriotism anil self-sacrifice after the disaster of Jena have given her a liigli place in the affections of the German nation. -

Ch. 3 Section 4: Life in the English Colonies Colonial Governments the English Colonies in North America All Had Their Own Governments

Ch. 3 Section 4: Life in the English Colonies Colonial Governments The English colonies in North America all had their own governments. Each government was given power by a charter. The English monarch had ultimate authority over all of the colonies. A group of royal advisers called the Privy Council set English colonial policies. Colonial Governors and Legislatures Each colony had a governor who served as head of the government. Most governors were assisted by an advisory council. In royal colonies the English king or queen selected the governor and the council members. In proprietary colonies, the proprietors chose all of these officials. In a few colonies, such as Connecticut, the people elected the governor. In some colonies the people also elected representatives to help make laws and set policy. These officials served on assemblies. Each colonial assembly passed laws that had to be approved first by the advisory council and then by the governor. Established in 1619, Virginia's assembly was the first colonial legislature in North America. At first it met as a single body, but was later split into two houses. The first house was known as the Council of State. The governor's advisory council and the London Company selected its members. The House of Burgesses was the assembly's second house. The members were elected by colonists. It was the first democratically elected body in the English colonies. In New England the center of politics was the town meeting. In town meetings people talked about and decided on issues of local interest, such as paying for schools. -

Holy Roman Empire

WAR & CONQUEST THE THIRTY YEARS WAR 1618-1648 1 V1V2 WAR & CONQUEST THE THIRTY YEARS WAR 1618-1648 CONTENT Historical Background Bohemian-Palatine War (1618–1623) Danish intervention (1625–1629) Swedish intervention (1630–1635) French intervention (1635 –1648) Peace of Westphalia SPECIAL RULES DEPLOYMENT Belligerents Commanders ARMY LISTS Baden Bohemia Brandenburg-Prussia Brunswick-Lüneburg Catholic League Croatia Denmark-Norway (1625-9) Denmark-Norway (1643-45) Electorate of the Palatinate (Kurpfalz) England France Hessen-Kassel Holy Roman Empire Hungarian Anti-Habsburg Rebels Hungary & Transylvania Ottoman Empire Polish-Lithuanian (1618-31) Later Polish (1632 -48) Protestant Mercenary (1618-26) Saxony Scotland Spain Sweden (1618 -29) Sweden (1630 -48) United Provinces Zaporozhian Cossacks BATTLES ORDERS OF BATTLE MISCELLANEOUS Community Manufacturers Thanks Books Many thanks to Siegfried Bajohr and the Kurpfalz Feldherren for the pictures of painted figures. You can see them and much more here: http://www.kurpfalz-feldherren.de/ Also thanks to the members of the Grimsby Wargames club for the pictures of painted figures. Homepage with a nice gallery this : http://grimsbywargamessociety.webs.com/ 2 V1V2 WAR & CONQUEST THE THIRTY YEARS WAR 1618-1648 3 V1V2 WAR & CONQUEST THE THIRTY YEARS WAR 1618-1648 The rulers of the nations neighboring the Holy Roman Empire HISTORICAL BACKGROUND also contributed to the outbreak of the Thirty Years' War: Spain was interested in the German states because it held the territories of the Spanish Netherlands on the western border of the Empire and states within Italy which were connected by land through the Spanish Road. The Dutch revolted against the Spanish domination during the 1560s, leading to a protracted war of independence that led to a truce only in 1609.