THE SOMERSETSHIRE COAL CANAL CAISSON LOCK Hugh Torrens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Ward and the K&A Canal

JohnWard and the Kennet and Avon Canal MichaelCorfield ln the progress of any great enterprise the record of events John Ward was a native of Staffordshire, born in Cheadle on that led to its fruition are often to be found in the off icial 30 June 1756, who came to Marlborough in Wiltshire to minutes of the concern. Behind those bland words lies a succeed his uncle, Charles Bill as agent to the Earl of weaith of controversy. lf the real reason for a particular Ailesbury. He became a leading citÌzen of Marlborough, course of action ís to be understood, then it is necessary to founded the Marlborough Bank and, as an attorney, started get beyond the official record and to have a víew ínto the a firm of solicitors which still practices in the town as committee room er the parlours of the members. To Ward Merriman's and Co; he was elected a memher of the examine the course of an event we need to find a personal Corporation and was Mayor several times. correspondence to or from someone tntimately connected with the event. The Ward family had a historic connection with the development of inland water transport. Whether or not ln the planning of the Kennet and Avon Canal we are John Ward was connected with the Earls of Dudley has yet fortunate that the læding landowner in the Marlborough to be demonstrated. However, one of the first proposals to area walthe Earl of Ailesbury, a leadíng figure ín court unite the Rivers Severn and Trent was proposed by Congreve circles whose duties kept him from his Savernake es'tates for in the 17th century in a pamphlet addressed to Sir Edward long periods. -

Openness & Accountability Mailing List

Openness & Accountability Mailing List AINA Amateur Rowing Association Anglers Conservation Association APCO Association of Waterway Cruising Clubs British Boating Federation British Canoe Union British Marine Federation Canal & Boat Builder’s Association CCPR Commercial Boat Operators Association Community Boats Association Country Landowners Association Cyclist’s Touring Club Historic Narrow Boat Owners Club Inland Waterways Association IWAAC Local Government Association NAHFAC National Association of Boat Owners National Community Boats Association National Federation of Anglers Parliamentary Waterways Group Rambler’s Association The Yacht Harbour Association Residential Boat Owner’s Association Royal Yachting Association Southern Canals Association Steam Boat Association Thames Boating Trades Association Thames Traditional Boat Society The Barge Association Upper Avon Navigation Trust Wooden Canal Boat Society ABSE AINA Amber Valley Borough Council Ash Tree Boat Club Ashby Canal Association Ashby Canal Trust Association of Canal Enterprises Aylesbury Canal Society 1 Aylesbury Vale District Council B&MK Trust Barnsley, Dearne & & Dover Canal Trust Barnet Borough Council Basingstoke Canal Authority Basingstoke Canal Authority Basingstoke Canal Authority Bassetlaw District Council Bath North East Somerset Council Bedford & Milton Keynes Waterway Trust Bedford Rivers Users Group Bedfordshire County Council Birmingham City Council Boat Museum Society Chair Bolton Metropolitan Council Borough of Milton Keynes Brent Council Bridge 19-40 -

Heritage Report 2015-2016

Heritage Report 2015/2016 November 2016 November 1 The Canal & River Trust cares for 2,000 miles of historic canals and river navigations in England and Wales – an internationally important landscape of heritage assets that is free for everyone to enjoy. Note: from August 2016 the Central Shires Waterways was absorbed into neighbouring waterways. 2 Case Studies The following case studies are included in the Report: Engine Arm Aqueduct Re-lining 7 Saul Junction Lock New Gates 8 Graffiti Removal in London 12 Winter Floods 2015 13 Nantwich Aqueduct Repairs 14 Grantham Canal Restoration 15 Re-lining Goytre Aqueduct 16 Dundas Toll House Restored 17 EveryMileCounts Project 18 Recovering Naburn Locks Workshops 19 Birmingham Roundhouse Partnership 20 Rebuilding a Dry Stone Wall 21 Art Meets Heritage 22 Heritage Training 23 Vale Royal Cottages Refurbishment 24 Diglis Workshop Re-used 25 Aldcliffe Yard Redevelopment 26 3 Foreword Managing and conserving the waterways heritage is one of the Trust’s most important objectives. In 2015/16 we again saw excellent work carried out to historic structures by our staff, volunteers and contractors. We also faced the challenges of the winter floods in late 2015 which caused significant damage to a number of our waterways and resulted in the failure of the Grade II listed Elland Bridge. On the property side of our business, for which we rely for much of our income, we made strong progress at a number of sites, including the high quality development at Aldcliffe Road on the Lancaster Canal. Our residential heritage refurbishment programme continues to roll forward and we have other schemes in the pipeline. -

Pearce Higgins, Selwyn Archive List

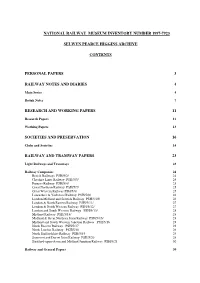

NATIONAL RAILWAY MUSEUM INVENTORY NUMBER 1997-7923 SELWYN PEARCE HIGGINS ARCHIVE CONTENTS PERSONAL PAPERS 3 RAILWAY NOTES AND DIARIES 4 Main Series 4 Rough Notes 7 RESEARCH AND WORKING PAPERS 11 Research Papers 11 Working Papers 13 SOCIETIES AND PRESERVATION 16 Clubs and Societies 16 RAILWAY AND TRAMWAY PAPERS 23 Light Railways and Tramways 23 Railway Companies 24 British Railways PSH/5/2/ 24 Cheshire Lines Railway PSH/5/3/ 24 Furness Railway PSH/5/4/ 25 Great Northern Railway PSH/5/7/ 25 Great Western Railway PSH/5/8/ 25 Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway PSH/5/9/ 26 London Midland and Scottish Railway PSH/5/10/ 26 London & North Eastern Railway PSH/5/11/ 27 London & North Western Railway PSH/5/12/ 27 London and South Western Railway PSH/5/13/ 28 Midland Railway PSH/5/14/ 28 Midland & Great Northern Joint Railway PSH/5/15/ 28 Midland and South Western Junction Railway PSH/5/16 28 North Eastern Railway PSH/5/17 29 North London Railway PSH/5/18 29 North Staffordshire Railway PSH/5/19 29 Somerset and Dorset Joint Railway PSH/5/20 29 Stratford-upon-Avon and Midland Junction Railway PSH/5/21 30 Railway and General Papers 30 EARLY LOCOMOTIVES AND LOCOMOTIVES BUILDING 51 Locomotives 51 Locomotive Builders 52 Individual firms 54 Rolling Stock Builders 67 SIGNALLING AND PERMANENT WAY 68 MISCELLANEOUS NOTEBOOKS AND PAPERS 69 Notebooks 69 Papers, Files and Volumes 85 CORRESPONDENCE 87 PAPERS OF J F BRUTON, J H WALKER AND W H WRIGHT 93 EPHEMERA 96 MAPS AND PLANS 114 POSTCARDS 118 POSTERS AND NOTICES 120 TIMETABLES 123 MISCELLANEOUS ITEMS 134 INDEX 137 Original catalogue prepared by Richard Durack, Curator Archive Collections, National Railway Museum 1996. -

Bath Avon River Economy

BATH AVON River Corridor Group BATH AVON RIVER ECONOMY FIRST REPORT OF BATH & NORTH EAST SOMERSET COUNCIL ADVISORY GROUP SUMMER 2011 Group Members The Bath Avon River Corridor Economy Advisory Group held its Inaugural Meeting in the Guildhall in Bath on 29th October 2010. Group members were nominated by Councillor Terry Gazzard or John Betty, Director of Development and Major Projects and North East Somerset Council, for their particular skills and relevant experience. Those present were: Michael Davis For experience in restoring the Kennet and Avon Canal Edward Nash For experience in urban regeneration and design management Jeremy Douch For experience in transport planning David Laming For experience in using the river for boating James Hurley Representing Low Carbon South West and for experience in resource efficiency Steve Tomlin For experience in reclamation of materials John Webb Representing Inland Waterways Association and the Kennet and Avon Canal Trust and experienced in Waterways management Nikki Wood For experience in water ecology Councillor Bryan Chalker For experience in Bath’s heritage and representing the Conservative Political Group Councillor Ian Gilchrist For experience in sustainability issues and representing the Liberal Democrats Political Group Melanie Birwe/ Tom Blackman For Bath and North East Somerset Council – liaison with Major Projects Office Steve Tomlin stood down in early 2011. CONTENTS 1. Introduction 9. The Role of the River in Flood Resilience 2. Executive Summary 10. Renewable Energy and Spatial Sustainability 3. The Problem and Its History 11. Creating Growth Points for Change a) The Geographic History b) The Challenges and Opportunities Now 12. Drivers of Economic Development c) The Regeneration Model • The Visitor Offer • University Sector 4. -

Discover Dundas Aqueduct

Discover Dundas Aqueduct The spectacular Dundas Aqueduct on the Claverton Kennet & Pumping Kennet & Avon Canal Bath Avon Canal Station is a Scheduled Ancient 6 3 Monument. That means A d it’s as important as a o Stonehenge! R r e t s n i m r River Avon a Dundas Crane Dundas W Basin Aqueduct Tollhouse lock keeper’s cottage Ken net & Avo n C Somerset an Coal Lift al Bridge Somerset Coal Canal (Somersetshire Coal Canal Society) Church Lane Bradford-on-Avon Avoncliff Aqueduct Little adventures on your doorstep Angel Fish Brass Knocker Basin STAY SAFE: Stay Away From Brassknocker the Edge Hill Map not to scale: covers approx 1.4 miles/2.4km A little bit of history John Rennie designed the Dundas Aqueduct and it’s regarded as his finest architectural achievement. He built it to carry the Kennet & Avon Canal across the wide Avon valley without the need for locks. Opened in 1805, it’s named after Charles Dundas, first chair of the Kennet & Avon Canal Company. Best of all it’s FREE!* ve thi Fi ngs to d o at D unda s Aque Information Walk down into the valley and view the aqueductduct Brassknocker Hill from below. It’s built of Bath stone that was Monkton Combe transported by the canal from local quarries. Bath BA2 7JD Look out for old canal features such as the crane for loading and unloading goods, and the lift bridge Parking at the entrance to the Somerset Coal Canal. Toilets Hire a bike and visit Avoncliff Aqueduct also built Restaurant by John Rennie and opened in 1801. -

Swansea Canal

Swansea Canal Clydach to Pontardawe Playing Fields Restoration Feasibility Study Swansea Canal Society 2013 Swansea Canal Clydach to Pontardawe Playing Fields Restoration Feasibility Study Client: Swansea Canal Society Funding: Inland Waterways Association Prepared By Patrick Moss Jennifer Smith Tamarisk Kay Nick Dowling Authorised for Issue By Patrick Moss Moss Naylor Young Limited 5 Oakdene Gardens Marple Stockport SK6 6PN Town Planning, Transport Planning, Waterway Regeneration Executive Summary This report, prepared by Moss Naylor Young Limited, has been commissioned by the Swansea Canal Society to examine a proposal to restore the Swansea Canal between Clydach and Trebanos. It examines at outline level the practicality, cost and potential benefits of restoration of the Swansea Canal from Clydach to Trebanos. This length of approximately four kilometres is assessed as a free standing scheme although it could also form part of the restoration of a longer length of canal if that were to proceed. This study has used as its core baseline document the Feasibility Report undertaken by WS Atkins in 2002. The genesis of this latest project is an apparent opportunity to reclaim the line of the canal through a depot site just to the east of the town of Clydach. The restoration is straight forward from an engineering perspective: the only significant obstacle is the infilling of the canal route across the depot site, and the canal line is more or less clear across this. The works to conceal the lock have, as far as can be ascertained, also worked to preserve it. Re-excavation of the canal and the lock would result in a continuous waterway linking the canal either side of the site. -

Weigh-House the Magazine of The

WEIGH-HOUSE THE MAGAZINE OF THE SOMERSETSHIRE COAL CANAL SOCIETY Website: http://www.coalcanal.org No 61 NOVEMBER 2011 Weigh-House 61 Weigh-House 61 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE The Somersetshire Coal Canal Society was founded in 1992 to: CHAIRMAN – PATRICK MOSS ‘FOCUS AN INTEREST ON THE PAST, PRESENT AND 3, Beech Court, Stonebridge Drive, Frome, Somerset BA11 2TY FUTURE OF THE OLD SOMERSETSHIRE COAL CANAL’ ( 07736 859882 E-mail: [email protected] VICE CHAIRMAN – DERRICK HUNT The Society became a registered charity in 1995 and now has the 43, Greenland Mills, Bradford on Avon, Wiltshire BA15 1BL Objects: ( 01225 863066 E-mail: [email protected] 1) To advance the education of the general public in the history of the SECRETARY – VACANT Somersetshire Coal Canal 2) The preservation and restoration of the Somersetshire Coal Canal TREASURER – DAVID CHALMERS and its structures for the benefit of the public ‘Shalom’ 40, Greenleaze, Knowle Park, Bristol BS4 2TL ( 0117 972 0423 MEMBERSHIP SECRETARY – JOHN BISHOP ******************************************************************************************* 73, Holcombe Green, Upper Weston, Bath BA14HY Registered Charity No 1047303 o ( 01225 428738 E-mail: [email protected] Registered under the Data Protection Act 1984 N A2697068 Affiliated to the Inland Waterways Association No 0005276 SECRETARY TO THE COMMITTEE – JOHN DITCHAM Inland Revenue reference code for tax purposes: CAD72QG 8, Entry Rise, Combe Down, Bath BA2 5LR ( 01225 832441 ******************************************************************************************* -

Walk West Again

This e-book has been laid out so that each walk starts on a left hand-page, to make printing the individual walks easier. You will have to use the PDF page numbers when you print, rather than the individual page numbers. When viewing on-screen, clicking on a walk below will take you to that walk in the book (pity it can’t take you straight to the start point of the walk itself!) As always, I’d be pleased to hear of any errors in the text or changes to the walks themselves. Happy walking! Walk Page Walks of up to 6 miles 1 East Bristol – Wick Rocks 1 2 West Bristol – The Bluebell Walk 3 3 Bristol – Snuff Mills & Oldbury Court 5 4 South Bristol – Dundry Hill 7 5 The Mendips – Burrington Ham 9 6 Chipping Sodbury – Three Sodburys 11 7 The Cotswolds – Two Hawkesburys 13 8 West Bristol – Blaise & Shirehampton 15 Walks of 6–8 miles 9 South Bristol – The Somerset Coal Canal (part 1) 17 10 South Bristol – The Somerset Coal Canal (part 2) 20 11 The Cotswolds – The Source of the Thames 23 12 Bristol – Conham & The Avon 26 13 The Wye Valley – Tintern 28 14 South Bristol – Backwell & Brockley 31 15 North Somerset – The Gordano Valley 33 Walks of 8–10 miles 16 South Gloucestershire – The Severn Estuary 36 17 Gloucestershire – Westonbirt & Highgrove 38 18 South Cotswolds – Slaughterford 41 19 The Cotswolds – Kingscote & Nailsworth 44 20 Gwent – Llanfoist 47 21 The Cotswolds – Painswick & Haresfield Beacon 50 22 Bath – Kelston & The Avon Valley 53 23 Somerset – The Somerset Levels 55 24 The Mendips – Wells & Wookey Hole 58 25 Gwent – Blaenavon & Blorenge -

G R O U P N E W S CONTENTS Editorial

NEWSLETTER 63 SPRING/SUMMER 2011 G R O U P N E W S CONTENTS Editorial.......................................................................................................................................................................... 1 MEETING REPORTS..................................................................................................................................................... 2 VISIT : THE VICTORIA ART GALLERY ......................................................................................................................... 2 THE INDUSTRIAL HERITAGE OF BATH: .................................................................................................................... 3 ACHIEVEMENTS AND PROSPECTS............................................................................................................................... 3 BATH AND THE ROYAL BATH AND WEST................................................................................................................ 4 THE KENNET AND AVON CANAL: ITS SIGNIFICANCE FOR BATH...................................................................... 6 WALK: BAILBROOK VILLAGE ....................................................................................................................................... 7 WALK: THE SOMERSET COAL CANAL. MIDFORD TO COMBE HAY................................................................... 8 BOOK REVIEWS & RECENT PUBLICATIONS................................................................................................... -

Memorandum to the Board

DECISION REPORT CRT80 TEXT IN RED CONFIDENTIAL MEMORANDUM TO THE BOARD GOVERNANCE REVIEW – MAY 2014 Report by the Chief Executive - May 2014 1.0 CONTEXT 1.1 Under the Canal & River Trust Rule 1.10, the composition and methods of appointment to the Council, which are defined by the Rules, are to be reviewed within three years from the date of appointment of the first Council and thereafter at least every seven years. 1.2 First Council was appointed in March 2012 and the review therefore needs to be completed by March 2015. Any changes should also be in place well in advance of preparations for the next elections to Council which are now proposed to take place in autumn 2015. 2.0 PROCESS 2.1 It is proposed that the Review is led by the Appointments Committee, working with members of the Executive and Secretariat nominated by the Chief Executive. 2.2 Under Rule 11.1, any changes to the Rules will be made by Council following a recommendation from the Trustees. The Appointments Committee recommendations would be considered by Trustees and once approved go to the Council for their agreement. 3.0 SCOPE 3.1 The main focus of this Review would be the Trust Rules as they relate to the Council. The Review will consider the outcome of the Council Election Consultation. The consultation is available http://canalrivertrust.org.uk/media/library/5254.pdf. The Council considered the response to the consultation at the March 2014 meeting. 3.2 The headline issues for consideration will be: size and make-up of Council – to include a possible increase in the size of Council from 35 to allow for election of members to represent Friends and Volunteers, or the inclusion of representatives from any new constituency groups identified. -

Canal Cruis Es 'PENNINE MOON RAKER' Why Not Join Us for a While on a Relaxing Canal B Oat Trip in Saddleworth?

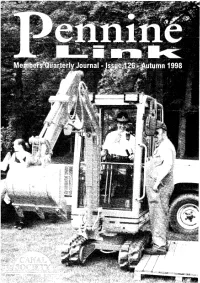

HCS Council Members Huddersfield Canal Society Ltd., 239, Mossley Road, Ashton-under-Lyne, Lancashire, OL6 6LN. Tel: 0161 339 1332 Fax: 0161 343 2262 Frank Smith : General Secretary e-mail: [email protected] David Sumner 4 Whiteoak Close, Marple, Stockport, Cheshire, SK6 6NT. Chairman Tel: 0161 449 9084 Trevor Ellis 20 Batley Avenue, Marsh, Huddersfield, HD1 4NA. Vice-Chairman Tel: 01484 534666 John Sully 5 Primley Park Road, Leeds, West Yorkshire, LS17 7HR. Treasurer Tel: 01132 685600 Jack Carr 19 Sycamore Avenue, Euxton, Chorley, Lancashire, PR7 6JR. West Side Social Chairman Tel: 01257 265786 Keith Gibson Syke Cottage, Scholes Moor Road, Scholes, Holmfirth, HD7 1SN. Chairman, HCS Restoration Ltd. Tel: 01484 681245 Josephine Young H.C.S. Ltd., 239 Mossley Road, Ashton-u-Lyne, Lancs., OL6 6LN. Membership Secretary Tel: 0161 339 1332 Brian Minor 45 Gorton Street, Peel Green, Eccles, Manchester, M30 7LZ. Festival Officer Tel: 0161 288 5324 Alec Ramsden 16 Edgemoor Road, Honley, Huddersfield, West Yorks, HD7 2HP. Press Officer Tel: 01484 662246 Pat Riley 1 Warlow Crest, Greenfield, Oldham, Lancashire,OL3 7HD. Sales Officer Tel: c/o H.C.S. on 0161 339 1332 Ken Wright Bridge House, Dobcross, Oldham, Lancashire, OL3 5NL. Editor- Pennine Link Tel: 01457 873599 Vince Willey 45 Egmont Street, Mossley, Ashton-u-Lyne, Lanes, OL5 9NB. Boats Officer Tel: c/o H.C.S. on 0161 339 1332 Alwyn Ogborn 10 Rothesay Avenue, Dukinfield, Cheshire, SK16 SAD. Special Events Co-ordinator Tel: 0161 339 0872 Alien Brett 31 Woodlands Road, Milnrow, Rochdale, Lancashire, OL 16 4EY. General Member Tel: 01706 641203 Keith Noble The Dene, Triangle, Sowerby Bridge, West Yorkshire, HX6 3EA.