Thomas Arnold, Christian Manliness and the Problem of Boyhood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yasha Gall, Julian Sorell Huxley, 1887-1975

Julian Sorell Huxley, 1887-1975 Yasha Gall Published by Nauka, St. Petersburg, Russia, 2004 Reproduced as an e-book with kind permission of Nauka Science editor: Academician AL Takhtajan Preface by the Science Editor The 20th century was the epoch of discovery in evolutionary biology, marked by many fundamental investigations. Of special significance were the works of AN Severtsov, SS Chetverikov, S Wright, JBS Haldane, G De Beer JS Huxley and R Goldschmidt. Among the general works on evolutionary theory, the one of greatest breadth was Julian Huxley’s book Evolution: The Modern Synthesis (1942). Huxley was one of the first to analyze the mechanisms of macro-evolutionary processes and discuss the evolutionary role of neoteny in terms of developmental genetics (the speed of gene action). Neoteny—the most important mechanism of heritable variation of ontogenesis—has great macro-evolutionary consequences. A Russian translation of Huxley’s book on evolution was prepared for publication by Professor VV Alpatov. The manuscript of the translation had already been sent to production when the August session of the VASKNIL in 1948 burst forth—a destructive moment in the history of biology in our country. The publication was halted, and the manuscript disappeared. I remember well a meeting with Huxley in 1945 in Moscow and Leningrad during the celebratory jubilee at the Academy of Sciences. He was deeply disturbed by the “blossoming” of Lysenkoist obscurantism in biology. It is also important to note that in the 1950s Huxley developed original concepts for controlling the birth rate of the Earth’s population. He openly declared the necessity of forming an international institute at the United Nations, since the global ecosystem already could not sustain the pressure of human “activity” and, together with humanity, might itself die. -

General Information for Applicants Facilities Manager the Princethorpe Foundation the Princethorpe Foundation, Which Is Administ

General information for applicants Facilities Manager The Princethorpe Foundation The Princethorpe Foundation, which is administered by lay trustees, provides co-educational, independent, day schooling in the Catholic tradition for some thirteen hundred children from age two to eighteen years. The senior school, Princethorpe College, (HMC 11 - 18) is about 7 miles from Leamington, Coventry and Rugby, with the junior schools, Crescent (IAPS) about seven miles away in Rugby, and Crackley Hall School (ISA and IAPS) and Little Crackers Nursery about nine miles away in Kenilworth. The Foundation’s schools are characterised by their strong Christian ethos and pride themselves on providing a caring, stimulating environment in which children’s individual needs are met and their talents, confidence and self-esteem are developed. The Schools Princethorpe College opened in 1966 and occupies a fine former Benedictine monastery which was built in the 1830s in 200 acres of parkland. The origins of the school date back to 1957 when the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart opened St Bede’s College in Leamington Spa; the subsequent move to Princethorpe gave an opportunity for expansion. The school became a lay foundation in 2001, when it merged with St Joseph’s School in Kenilworth, resulting in the consolidation of a junior school and nursery on the Kenilworth campus. Crackley Hall is a significant feeder for Princethorpe. In September 2016, The Crescent School, a stand-alone prep school for seventy years in Rugby, also merged with the Princethorpe Foundation. Princethorpe life extends well beyond just exam preparation. The gospel values of love, service, commitment and forgiveness are central to everything which the school does, underscored by the school motto, Christus Regnet – may Christ reign. -

Letters from Arthur Penrhyn Stanley, (NLW MS 12877C.)

Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Cymorth chwilio | Finding Aid - Letters from Arthur Penrhyn Stanley, (NLW MS 12877C.) Cynhyrchir gan Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Argraffwyd: Mai 08, 2017 Printed: May 08, 2017 Wrth lunio'r disgrifiad hwn dilynwyd canllawiau ANW a seiliwyd ar ISAD(G) Ail Argraffiad; rheolau AACR2; ac LCSH Description follows NLW guidelines based on ISAD(G) 2nd ed.; AACR2; and LCSH https://archifau.llyfrgell.cymru/index.php/letters-from-arthur-penrhyn-stanley archives.library .wales/index.php/letters-from-arthur-penrhyn-stanley Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Allt Penglais Aberystwyth Ceredigion United Kingdom SY23 3BU 01970 632 800 01970 615 709 [email protected] www.llgc.org.uk Letters from Arthur Penrhyn Stanley, Tabl cynnwys | Table of contents Gwybodaeth grynodeb | Summary information .............................................................................................. 3 Natur a chynnwys | Scope and content .......................................................................................................... 3 Nodiadau | Notes ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Pwyntiau mynediad | Access points ............................................................................................................... 4 Llyfryddiaeth | Bibliography .......................................................................................................................... -

Tom Brown's Schooldays

TOM BROWN’S SCHOOLDAYS: DISCOVERING A VICTORIAN HEADMASTER IN RUGBY PUBLIC SCHOOL * CORTÉS GRANELL , Ana María Universitat de València Departament de Filologia Anglesa i Alemanya [email protected] Fecha de recepción: 11 de julio de 2013 Fecha de aceptación: 27 de julio de 2013 Título: Los días de escuela de Tom Brown: Descubriendo a un director victoriano en la Escuela Pública Rugby Resumen: Este artículo presenta la hipótesis que Thomas Arnold (1795-1842) mejoró y modeló al niño inglés medio para el Imperio Británico mientras que desempeñaba la función de director en la escuela pública Rugby (1828-1842). El estudio comienza por la introducción de la escuela pública en cuanto a su evolución y causas, además del nacimiento del mito de Arnold. La novela Tom Brown’s Schooldays de Thomas Hughes sirve para desarrollar nuestro entendimiento de lo genuino inglés a través del examen de una escuela pública modelo y sus constituyentes. Hemos realizado un análisis del personaje de Thomas Arnold mediante la comparación de un estudio de caso a partir de la novela de Hughes y dos películas adaptadas por Robert Stevenson (1940) y David Moore (2005). En las conclusiones ofrecemos la tesis que Thomas Arnold sólo pudo inculcar sus ideas por medio del antiguo sistema de los prefectos. Palabras clave: escuela pública, Rugby, Thomas Arnold, Thomas Hughes, inglés, prefecto. * This article was submitted for the subject Bachelor’s Degree Final Dissertation, and was supervised by Dr Laura Monrós Gaspar, lecturer in English Literature at the English and German Studies Department at the Universitat de València. Philologica Urcitana Revista Semestral de Iniciación a la Investigación en Filología Vol. -

The Armstrong Browning Library Newsletter God Is the Perfect Poet

The Armstrong Browning Library Newsletter God is the perfect poet. – Paracelsus by Robert Browning NUMBER 51 SPRING/SUMMER 2007 WACO, TEXAS Ann Miller to be Honored at ABL For more than half a century, the find inspiration. She wrote to her sister late Professor Ann Vardaman Miller of spending most of the summer there was connected to Baylor’s English in the “monastery like an eagle’s nest Department—first as a student (she . in the midst of mountains, rocks, earned a B.A. in 1949, serving as an precipices, waterfalls, drifts of snow, assistant to Dr. A. J. Armstrong, and a and magnificent chestnut forests.” master’s in 1951) and eventually as a Master Teacher of English herself. So Getting to Vallombrosa was not it is fitting that a former student has easy. First, the Brownings had to stepped forward to provide a tribute obtain permission for the visit from to the legendary Miller in Armstrong the Archbishop of Florence and the Browning Library, the location of her Abbot-General. Then, the trip itself first campus office. was arduous—it involved sitting in a wine basket while being dragged up the An anonymous donor has begun the cliffs by oxen. At the top, the scenery process of dedicating a stained glass was all the Brownings had dreamed window in the Cox Reception Hall, on of, but disappointment awaited Barrett the ground floor of the library, to Miller. Browning. The monks of the monastery The Vallombrosa Window in ABL’s Cox Reception The hall is already home to five windows, could not be persuaded to allow a woman Hall will be dedicated to the late Ann Miller, a Baylor professor and former student of Dr. -

UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Bower of Books: Reading Children in Nineteenth-Century British Literature Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/89q0q765 Author Browning, Catherine Cronquist Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Bower of Books: Reading Children in Nineteenth-Century British Literature By Catherine Cronquist Browning A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Ian Duncan, Chair Professor Catherine Gallagher Professor Paula Fass Fall 2013 Bower of Books: Reading Children in Nineteenth-Century British Literature © 2013 by Catherine Cronquist Browning Abstract Bower of Books: Reading Children in Nineteenth-Century British Literature by Catherine Cronquist Browning Doctor of Philosophy in English University of California, Berkeley Professor Ian Duncan, Chair Bower of Books: Reading Children in Nineteenth-Century British Literature analyzes the history of the child as a textual subject, particularly in the British Victorian period. Nineteenth-century literature develops an association between the reader and the child, linking the humanistic self- fashioning catalyzed by textual study to the educational development of children. I explore the function of the reading and readable child subject in four key Victorian genres, the educational treatise, the Bildungsroman, the child fantasy novel, and the autobiography. I argue that the literate children of nineteenth century prose narrative assert control over their self-definition by creatively misreading and assertively rewriting the narratives generated by adults. The early induction of Victorian children into the symbolic register of language provides an opportunity for them to constitute themselves, not as ingenuous neophytes, but as the inheritors of literary history and tradition. -

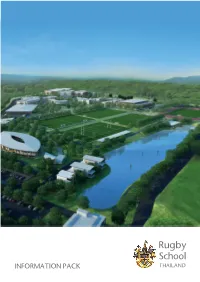

Information Pack Contents

INFORMATION PACK CONTENTS 1 OUR FOUNDING HEAD MASTER 3 RUGBY SCHOOL THAILAND 4 THE SCHOOL SITE 6 7 LIVING IN THAILAND 8 THE TEEPSUWAN FAMILY 9 RUGBY SCHOOL UK 10 “THE WHOLE PERSON IS THE WHOLE POINT” 11 REMUNERATION PACKAGE 12 HOW TO APPLY OUR FOUNDING HEAD MASTER NIGEL WESTLAKE Nigel Westlake has had 30 years experience in the UK independent education sector, 15 years as a Head. He qualified initially as a solicitor, before switching careers to become a schoolmaster at Sunningdale, The Old Malthouse and Aldro prep schools. His roles included Head of English and Drama, Director of Sport, Boarding Housemaster and Deputy Head. Whilst Head Master at Packwood Haugh and Brambletye Prep Schools, he oversaw significant increases in pupil intake and record scholarships. Nigel’s wife, Jo, is a trained concert pianist and was a highly-successful Director of Music at Packwood Haugh. She began her class music teaching career at Bangkok Patana – a highly-regarded international school in Thailand. By the time Rugby school Thailand opens, Nigel will have been involved in the development of the project for two years. He says: “I believe Rugby School Thailand offers a unique opportunity to bring the very best of the UK independent sector to Thailand. The quality of the site, the commitment of the owners and the support of Rugby School UK combine to offer something very distinct and very special. “Of course, a further key ingredient is an outstanding school staff. We are seeking to appoint teachers with character, teachers who can inspire, teachers who are prepared to go the extra mile to help the children flourish. -

Brave New World Book Notes

Brave New World Book Notes Brave New World by Aldous Huxley The following sections of this BookRags Literature Study Guide is offprint from Gale's For Students Series: Presenting Analysis, Context, and Criticism on Commonly Studied Works: Introduction, Author Biography, Plot Summary, Characters, Themes, Style, Historical Context, Critical Overview, Criticism and Critical Essays, Media Adaptations, Topics for Further Study, Compare & Contrast, What Do I Read Next?, For Further Study, and Sources. (c)1998-2002; (c)2002 by Gale. Gale is an imprint of The Gale Group, Inc., a division of Thomson Learning, Inc. Gale and Design and Thomson Learning are trademarks used herein under license. The following sections, if they exist, are offprint from Beacham's Encyclopedia of Popular Fiction: "Social Concerns", "Thematic Overview", "Techniques", "Literary Precedents", "Key Questions", "Related Titles", "Adaptations", "Related Web Sites". (c)1994-2005, by Walton Beacham. The following sections, if they exist, are offprint from Beacham's Guide to Literature for Young Adults: "About the Author", "Overview", "Setting", "Literary Qualities", "Social Sensitivity", "Topics for Discussion", "Ideas for Reports and Papers". (c)1994-2005, by Walton Beacham. All other sections in this Literature Study Guide are owned and copyrighted by BookRags, Inc. Contents Brave New World Book Notes ...................................................................................................... 1 Contents ..................................................................................................................................... -

Tom Brown's Schooldays and the Development of "Muscular Christianity" Author(S): William E

American Society of Church History Tom Brown's Schooldays and the Development of "Muscular Christianity" Author(s): William E. Winn Source: Church History, Vol. 29, No. 1 (Mar., 1960), pp. 64-73 Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of the American Society of Church History Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3161617 . Accessed: 24/07/2011 20:08 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at . http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=cup. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Cambridge University Press and American Society of Church History are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Church History. -

Information Pack Contents

INFORMATION PACK CONTENTS 1 HEAD OF PREP AND FOUNDING HEAD MASTER 3 HEAD OF SENIOR SCHOOL 4 RUGBY SCHOOL THAILAND 6 THE SCHOOL SITE 7 LIVING IN THAILAND 9 THE TEEPSUWAN FAMILY 10 RUGBY SCHOOL UK 11 “THE WHOLE PERSON IS THE WHOLE POINT” 12 REMUNERATION PACKAGE AND HOW TO APPLY HEAD OF PREP AND FOUNDING HEAD MASTER NIGEL WESTLAKE Nigel Westlake has had 30 years experience in the UK independent education sector, 15 years as a Head. He qualified initially as a solicitor, before switching careers to become a schoolmaster at Sunningdale, The Old Malthouse and Aldro prep schools. His roles included Head of English and Drama, Director of Sport, Boarding Housemaster and Deputy Head. Whilst Head Master at Packwood Haugh and Brambletye Prep Schools, he oversaw significant increases in pupil intake and record scholarships. Nigel’s wife, Jo, is a trained concert pianist and was a highly-successful Director of Music at Packwood Haugh. She began her class music teaching career at Bangkok Patana – a highly-regarded international school in Thailand. As Founding Head, Nigel has been involved in the development of Rugby School Thailand for two years prior to its opening in September 2017. He says: “I believe Rugby School Thailand offers a unique opportunity to bring the very best of the UK independent sector to Thailand. The quality of the site, the commitment of the owners and the support of Rugby School UK combine to offer something very distinct and very special. “Of course, a further key ingredient is an outstanding school staff. We are seeking to appoint teachers with character, teachers who can inspire, teachers who are prepared to go the extra mile to help the children flourish. -

Rugby School CA

RUGBY BOROUGH COUNCIL RUGBY SCHOOL CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL June 2010 CONTENTS Page 1 Introduction 3 2 Location and context 5 3 General character and form 7 4 Landscape setting 8 5 Historic development 10 6 Archaeology 12 7 Architecture, buildings and features 14 8 Detailed Architectural Assessment 16 Area 1: Rugby School, Oak Street, Barby Road 17 Area 2: Horton Crescent 23 Area 3: Hillmorton Road, Moultaire Road, Church Walk, Elsee Road 26 9 Contribution of unlisted buildings 31 10 Street furniture 32 11 Key views and vistas 33 12 Existence of any neutral areas 34 13 Conclusions 34 14 Preservation and enhancement 35 15 Appendices 37 2 INTRODUCTION Rugby School Conservation Area is a designation which borders the Town Centre, Bilton Road and Hillmorton/Whitehall and Clifton Road Conservation Areas. It occupies a prominent location and acts as a transition between the commercial, education and residential areas on the southern edge of the town centre. The area is dominated by the monumental scale Gothic buildings of William Butterfield on Lawrence Sheriff Street and Dunchurch Road. Along Barby Road, Horton Crescent and Hillmorton Road Gothic, Arts and Crafts and classical buildings occupy large landscaped sites. In the northern part of the Conservation Area there are late Victorian/Edwardian dwellings. The Conservation Area lies at an important location with roads leading to Dunchurch, Hillmorton and Barby from the gyratory, which lies to the west. Roads are a key visual element in the designation with buildings set abutting on the north-west and western boundaries. The area is dominated by the school with classrooms, dormitories and playing fields prominently sited. -

Sydney Smith (1771-1845)

26 HE LOVES LIBERTY—BUT NOT TOO MUCH OF IT SYDNEY SMITH (1771-1845) hile strong emotions flood many of Robert Burns’s letters, a cool wit gives Wlife and charm to most of Sydney Smith’s. Their attractiveness increases as he ad- vances from obscurity as a young curate and tu- tor to fame as a polemicist and a renowned wit. His collected correspondence has the structure of a funnel. Beginning with his reports on the two sons of the parliamentarian Michael Hicks Beach, whom he successsively lives with and instructs in Edinburgh, it expands to cover, first, his en- gagement with figures of the Scottish Enlightenment, and then his close in- volvement with the English Whig aristocracy and the causes they promote, and his public foray into the politics of the Anglican Church. During his residence in Edinburgh from 1798 to 1803, Smith forms friendships with Francis Jeffrey and other intellectuals: together they found the Edinburgh Review, which becomes the leading liberal journal in Britain, a kingdom that still suffers from a paranoid fear that even mild reforms can lead in time to atrocities akin to those of the French Revolution. In 1803, as a recently married man and a new father, he reluctantly leaves the Scottish capital in search of support for his growing family, and moves to London. Here he preaches, gives highly popular lectures on moral philosophy, and is soon in demand as a captivating guest at dinner parties. Before long, he is intimate at Holland House, the social centre of the Whigs, whose reform- ist zeal he shares.