The Lace Bobbins of East Devon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Palmetto Tatters Guild Glossary of Tatting Terms (Not All Inclusive!)

Palmetto Tatters Guild Glossary of Tatting Terms (not all inclusive!) Tat Days Written * or or To denote repeating lines of a pattern. Example: Rep directions or # or § from * 7 times & ( ) Eg. R: 5 + 5 – 5 – 5 (last P of prev R). Modern B Bead (Also see other bead notation below) notation BTS Bare Thread Space B or +B Put bead on picot before joining BBB B or BBB|B Three beads on knotting thread, and one bead on core thread Ch Chain ^ Construction picot or very small picot CTM Continuous Thread Method D Dimple: i.e. 1st Half Double Stitch X4, 2nd Half Double Stitch X4 dds or { } daisy double stitch DNRW DO NOT Reverse Work DS Double Stitch DP Down Picot: 2 of 1st HS, P, 2 of 2nd HS DPB Down Picot with a Bead: 2 of 1st HS, B, 2 of 2nd HS HMSR Half Moon Split Ring: Fold the second half of the Split Ring inward before closing so that the second side and first side arch in the same direction HR Half Ring: A ring which is only partially closed, so it looks like half of a ring 1st HS First Half of Double Stitch 2nd HS Second Half of Double Stitch JK Josephine Knot (Ring made of only the 1st Half of Double Stitch OR only the 2nd Half of Double Stitch) LJ or Sh+ or SLJ Lock Join or Shuttle join or Shuttle Lock Join LPPCh Last Picot of Previous Chain LPPR Last Picot of Previous Ring LS Lock Stitch: First Half of DS is NOT flipped, Second Half is flipped, as usual LCh Make a series of Lock Stitches to form a Lock Chain MP or FP Mock Picot or False Picot MR Maltese Ring Pearl Ch Chain made with pearl tatting technique (picots on both sides of the chain, made using three threads) P or - Picot Page 1 of 4 PLJ or ‘PULLED LOOP’ join or ‘PULLED LOCK’ join since it is actually a lock join made after placing thread under a finished ring and pulling this thread through a picot. -

NEEDLE LACES Battenberg, Point & Reticella Including Princess Lace 3Rd Edition

NEEDLE LACES BATTENBERG, POINT & RETICELLA INCLUDING PRINCESS LACE 3RD EDITION EDITED BY JULES & KAETHE KLIOT LACIS PUBLICATIONS BERKELEY, CA 94703 PREFACE The great and increasing interest felt throughout the country in the subject of LACE MAKING has led to the preparation of the present work. The Editor has drawn freely from all sources of information, and has availed himself of the suggestions of the best lace-makers. The object of this little volume is to afford plain, practical directions by means of which any lady may become possessed of beautiful specimens of Modern Lace Work by a very slight expenditure of time and patience. The moderate cost of materials and the beauty and value of the articles produced are destined to confer on lace making a lasting popularity. from “MANUAL FOR LACE MAKING” 1878 NEEDLE LACES BATTENBERG, POINT & RETICELLA INLUDING PRINCESS LACE True Battenberg lace can be distinguished from the later laces CONTENTS by the buttonholed bars, also called Raleigh bars. The other contemporary forms of tape lace use the Sorrento or twisted thread bar as the connecting element. Renaissance Lace is INTRODUCTION 3 the most common name used to refer to tape lace using these BATTENBERG AND POINT LACE 6 simpler stitches. Stitches 7 Designs 38 The earliest product of machine made lace was tulle or the PRINCESS LACE 44 RETICELLA LACE 46 net which was incorporated in both the appliqued hand BATTENBERG LACE PATTERNS 54 made laces and later the elaborate Leavers laces. It would not be long before the narrow tapes, in fancier versions, would be combined with this tulle to create a popular form INTRODUCTION of tape lace, Princess Lace, which became and remains the present incarnation of Belgian Lace, combining machine This book is a republication of portions of several manuals made tapes and motifs, hand applied to machine made tulle printed between 1878 and 1938 dealing with varieties of and embellished with net embroidery. -

Bobbin Lace You Need a Pattern Known As a Pricking

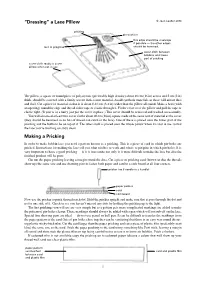

“Dressing” a Lace Pillow © Jean Leader 2014 pricking pin-cushion this edge should be a selvage if possible — the other edges lace in progress should be hemmed. cover cloth between bobbins and lower part of pricking cover cloth ready to cover pillow when not in use The pillow, a square or round piece of polystyrene (preferably high density) about 40 cm (16 in) across and 5 cm (2 in) thick, should be covered with a firmly woven dark cotton material. Avoid synthetic materials as these will attract dust and fluff. Cut a piece of material so that it is about 8-10 cm (3-4 in) wider than the pillow all round. Make a hem (with an opening) round the edge and thread either tape or elastic through it. Fit the cover over the pillow and pull the tape or elastic tight. (If you’re in a hurry just pin the cover in place.) This cover should be removed and washed occasionally. You will also need at least two cover cloths about 40 cm (16 in) square made of the same sort of material as the cover (they should be hemmed so no bits of thread can catch in the lace). One of these is placed over the lower part of the pricking and the bobbins lie on top of it. The other cloth is placed over the whole pillow when it is not in use so that the lace you’re working on stays clean. Making a Pricking In order to make bobbin lace you need a pattern known as a pricking. -

Powerhouse Museum Lace Collection: Glossary of Terms Used in the Documentation – Blue Files and Collection Notebooks

Book Appendix Glossary 12-02 Powerhouse Museum Lace Collection: Glossary of terms used in the documentation – Blue files and collection notebooks. Rosemary Shepherd: 1983 to 2003 The following references were used in the documentation. For needle laces: Therese de Dillmont, The Complete Encyclopaedia of Needlework, Running Press reprint, Philadelphia, 1971 For bobbin laces: Bridget M Cook and Geraldine Stott, The Book of Bobbin Lace Stitches, A H & A W Reed, Sydney, 1980 The principal historical reference: Santina Levey, Lace a History, Victoria and Albert Museum and W H Maney, Leeds, 1983 In compiling the glossary reference was also made to Alexandra Stillwell’s Illustrated dictionary of lacemaking, Cassell, London 1996 General lace and lacemaking terms A border, flounce or edging is a length of lace with one shaped edge (headside) and one straight edge (footside). The headside shaping may be as insignificant as a straight or undulating line of picots, or as pronounced as deep ‘van Dyke’ scallops. ‘Border’ is used for laces to 100mm and ‘flounce’ for laces wider than 100 mm and these are the terms used in the documentation of the Powerhouse collection. The term ‘lace edging’ is often used elsewhere instead of border, for very narrow laces. An insertion is usually a length of lace with two straight edges (footsides) which are stitched directly onto the mounting fabric, the fabric then being cut away behind the lace. Ocasionally lace insertions are shaped (for example, square or triangular motifs for use on household linen) in which case they are entirely enclosed by a footside. See also ‘panel’ and ‘engrelure’ A lace panel is usually has finished edges, enclosing a specially designed motif. -

Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace Identification

Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace DATS in partnership with the V&A DATS DRESS AND TEXTILE SPECIALISTS 1 Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace Text copyright © Jeremy Farrell, 2007 Image copyrights as specified in each section. This information pack has been produced to accompany a one-day workshop of the same name held at The Museum of Costume and Textiles, Nottingham on 21st February 2008. The workshop is one of three produced in collaboration between DATS and the V&A, funded by the Renaissance Subject Specialist Network Implementation Grant Programme, administered by the MLA. The purpose of the workshops is to enable participants to improve the documentation and interpretation of collections and make them accessible to the widest audiences. Participants will have the chance to study objects at first hand to help increase their confidence in identifying textile materials and techniques. This information pack is intended as a means of sharing the knowledge communicated in the workshops with colleagues and the public. Other workshops / information packs in the series: Identifying Textile Types and Weaves 1750 -1950 Identifying Printed Textiles in Dress 1740-1890 Front cover image: Detail of a triangular shawl of white cotton Pusher lace made by William Vickers of Nottingham, 1870. The Pusher machine cannot put in the outline which has to be put in by hand or by embroidering machine. The outline here was put in by hand by a woman in Youlgreave, Derbyshire. (NCM 1912-13 © Nottingham City Museums) 2 Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace Contents Page 1. List of illustrations 1 2. Introduction 3 3. The main types of hand and machine lace 5 4. -

Annual Report 2010-2011

Incorporating community services in Exeter, East and Mid Devon AAnnualnnual RReporteport 2010 - 2011 Northern Devon Healthcare NHS Trust 2 CContentsontents Introduction . 3 Trust background . 4 Our area . 7 Our community . 7 Transforming Community Services (TCS) . 7 Our values . 7 Our vision . 7 Patient experience . 9 What you thought in 2010-11 . 10 Telling us what you think . .12 Investment in services for patients . 13 Keeping patients informed . 15 Outpatient reminder scheme launched in April 2011 . 15 Involving patients and the public in improving services . 16 Patient Safety . .17 Safe care in a safe environment . .18 Doing the rounds . 18 Preventing infections . 18 Norovirus . 18 A learning culture . 19 High ratings from staff . .20 Performance . 21 Value for money . 22 Accountability . 22 Keeping waiting times down . 22 Meeting the latest standards . 22 Customer relations . 23 Effective training and induction . .24 Dealing with violence and aggression . 24 Operating and Financial Review . 25 Statement of Internal Control . 39 Remuneration report . .46 Head of Intenal Audit opinion . 50 Accounts . 56 Annual Report 2010 - 11 3 IIntroductionntroduction Running a complex organisation is about ensuring that standards are maintained and improved at the everyday level while taking the right decisions for the longer term. The key in both hospital and community-based services is to safeguard the quality of care and treatment for patients. That underpins everything we do. And as this report shows, there were some real advances last year. For example, our new service for people with wet, age-related macular degeneration (WAMD) – a common cause of blindness – was recognised as among the best in the South West. -

East Devon Conservative Association

East Devon Conservative Association Link 9c Mill Park Industrial Estate White Cross Road Woodbury Salterton EX5 1EL Tel: 01395 233503 Email: [email protected] August 2013 Printed & promoted by Lucille Baker on behalf of EDCA both of 9c Mill Park, EX5 1EL THE CASE FOR A REFERENDUM It has been nearly 40 years since the British people last had their say on Europe. In that time, so much has changed - the countries involved, the powers devolved, the benefits and costs of membership. People feel that the EU is heading in a direction they never signed up for. It is right to negotiate a fresh settlement in the EU that is better for Britain - and then put the result to the British people in an in-out SUPPORT THE CAMPAIGN: referendum by the end of 2017. This isn't just a www.letbritaindecide.com Conservative campaign - it's for everyone who believes that we need a different relationship with the EU and that the British people deserve SOUTH WEST MEP CANDIDATE a say. RESULTS Over the last month, Conservative members have been balloted to choose the candidates and their position on the ballot paper for next year’s European Elections. Conservatives are the only party to have backed the campaign to ‘Let Britain Decide’ in a referendum on the EU, following a renegotiation, by the end of 2017. Conservative MEPs have joined David Cameron in standing up for Britain in Europe, something Labour failed to do in over a decade in office. Grant Shapps, Conservative Party Chairman, said; “For 13 years Labour handed power to Brussels. -

Dorset and East Devon Coast for Inclusion in the World Heritage List

Nomination of the Dorset and East Devon Coast for inclusion in the World Heritage List © Dorset County Council 2000 Dorset County Council, Devon County Council and the Dorset Coast Forum June 2000 Published by Dorset County Council on behalf of Dorset County Council, Devon County Council and the Dorset Coast Forum. Publication of this nomination has been supported by English Nature and the Countryside Agency, and has been advised by the Joint Nature Conservation Committee and the British Geological Survey. Maps reproduced from Ordnance Survey maps with the permission of the Controller of HMSO. © Crown Copyright. All rights reserved. Licence Number: LA 076 570. Maps and diagrams reproduced/derived from British Geological Survey material with the permission of the British Geological Survey. © NERC. All rights reserved. Permit Number: IPR/4-2. Design and production by Sillson Communications +44 (0)1929 552233. Cover: Duria antiquior (A more ancient Dorset) by Henry De la Beche, c. 1830. The first published reconstruction of a past environment, based on the Lower Jurassic rocks and fossils of the Dorset and East Devon Coast. © Dorset County Council 2000 In April 1999 the Government announced that the Dorset and East Devon Coast would be one of the twenty-five cultural and natural sites to be included on the United Kingdom’s new Tentative List of sites for future nomination for World Heritage status. Eighteen sites from the United Kingdom and its Overseas Territories have already been inscribed on the World Heritage List, although only two other natural sites within the UK, St Kilda and the Giant’s Causeway, have been granted this status to date. -

All About Macramé History of Macramé

August 2019 Newsletter All about Macramé For August we thought we would ring the changes and dedicate this edition of the newsletter to a fibre art that was popular in the 1970’s and 80’s for making wall hangings and potholders but which has recently made a resurgence in fibre art. Some customers have also found that the weaversbazaar cotton and linen warps are ideally suited to macramé. So we have all been having a go. Dianne Miles, one of the weaversbazaar tutors, has extensive experience in Macramé and has designed a one day course to show how the techniques can be incorporated into Tapestry for stunning effect – more details below. So we would like to show you some of the best work going on and introduce you to some of the cross overs with other textile art. History of Macramé The earliest recorded macramé knots appear in decorative carvings of the Babylonians and Assyrians. Macramé was introduced to Europe via Spain during its conquest by the Moors and the word is believed to derive from a 13th century Arabic weavers term meaning fringe as the knots were used to turn excess yarn into decorative edges to finish hand woven fabrics. Probably introduced to England by Queen Mary in the late 17th century it was also practiced by sailors who made decorative objects (such as hammocks, belts etc.) whilst at sea thereby disseminating it even further afield when they sold their work in port. It was also known as McNamara’s Lace. The Victorians loved macramé for “rich trimming” for clothing and household items with a favourite book being “Sylvia’s Book of Macramé Lace” which is still available today. -

Pelvic Floor Muscles (Women)

The pelvic floor muscles (women) Bladder and Bowel Care Service East Devon − Franklyn House, St Thomas, Exeter Tel: 01392 208478 South Devon − Newton Abbot Hospital Tel: 01626 324685 North and Mid Devon − Crown Yealm House, South Molton Tel: 01392 675336 Other formats If you need this information in another format such as audio CD, Braille, large print, high contrast, British Sign Language or translated into another language, please contact the PALS desk on 01271 314090 or at [email protected]. What and where are they? The pelvic floor muscles are at the bottom of your pelvis. They attach to the pubic bone at the front to the coccyx (tail bone) at the back. What does the pelvic floor do? The muscles of the pelvic floor work like a hammock, to support the pelvic organs (bladder, womb and bowel). The pelvic floor muscles also help close the outlets from the bladder and bowel, keeping you clean and dry. Strong pelvic floor muscles can also help increase sexual enjoyment. Leaflet number: 047 / Version number: 3 / Review due date: December 2022 1 of 4 Northern Devon Healthcare NHS Trust Why do I need to exercise my pelvic floor? All muscles need to be exercised to stay strong. The pelvic floor muscles can be weakened in several ways, e.g. • Childbirth and pregnancy • Excess weight • Chest problems causing coughs • Long term constipation • Ageing Strengthening the pelvic floor can improve bladder and bowel control, and also support the pelvic organs, helping to prevent prolapse. How do I find my pelvic floor? Sit comfortably on a firm chair and try to keep breathing normally. -

African Lace

Introduction Does changing an original material destroy its traditional context? If a material assumes new meaning or significance in a new context, is this inherently an appropriation of the object? What loss does this cause, and is it a positive change, a negative one, or neither? This lexicon revolves around African Lace. Through an analysis of this particular material, I broadly explain, craftsmanship, authenticity and reasons behind an object’s creation, including why and how it is made, from which materials, and how the object translates into a specific environment. Various kinds of objects are created in and relate to specific places and time periods. If situated in an environment in which it did not originate, the meaning of an object changes. In fact, the object is used from a new perspective. Although it is possible to reuse an object as a source of inspiration or research, it cannot be used as it was in its previous context. Thus, it is necessary to rethink the authenticity of an object when it is removed from its past context. History is important and can explain a materials origin, and it therefore warrants further attention. A lack of knowledge results in a loss of authenticity and originality of a historical material. In view of this, I develop this Lexicon to elaborate on the importance of this historical attention. It is interesting to consider how an object can influence a user in relation to emotional or even material value. The extent of this influence is uncertain, but it is a crucial aspect since any situation could diminish the value and the meaning of an object. -

Sheila Machines in Switzerland Are Busy As I Write, Re- Running Some Old Favorites

Bear in Mind An electronic newsletter from Bear Threads Ltd. Volume 10 – Issue 6 June/July 2018 From The Editor – however, is that we will be introducing some gorgeous NEW embroideries in our next issue – “A rainy day in Georgia” indeed as Alberto dumps August. These are beautiful designs and very more rain on our soggy ground. But a great much in line with our two-part feature on Broidere stitching week as well, as we are officially into Anglaise. summer, albeit not by the calendar!!! I gathered supplies for my summer stitching projects before And put the date of Sunday, September 9, 2018 on the Memorial Day weekend, my porches are clean your calendar NOW to make sure you can see us and everything ready for summer sipping and at the Birmingham Creative Sewing Market. I stitching. assure you, it would be tragic not to be one of the first to see the new Swiss Broderie Anglaise Remember that we publish ‘Bear In Mind’ 10 times embroideries, as well as our newest lace set. And a year, combining June and July as well as for icing on the cake we will have certain Maline November and December. So this issue is really laces available for ½ price – guess that your eyes not late, but rather we are stretching the lazy days and ears perked up!!! of summer. We have definitely not been lazy here at the office, as the website now has been updated So for now, enjoy your summer, be saving your with the newsletter index, our newest lace set, and money for September, and all the past newsletters.