Get Downfield Before the Ball Lands, Pos- Mation Would Be Required to Properly Appropriate Sibly Reducing Return Opportunities, Thus Increasing Blame for These Mishaps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rebuilding of New Orleans

Lighting The Road To Freedom Data Zone Page 8 August Wilson’s Fences “The People’s Paper” September 23, 2006 40th Year Volume 36 www.ladatanews.com The Soul of New Orleans 100 Days and Counting The Rebuilding of New Orleans Page 2 VOTER PROTECTION HOTLINE 1-866-OUR-VOTE For the Louisiana Primary Elections TrailBlazer | The Ameede Family Saturday, September 30th, 2006 Page 4 Page September 3, 006 New Orleans Data News Weekly www.ladatanews.com COVER STORY Ray Nagin and Rebuilding New Orleans: One-Hundred Days and Counting Written By: Edwin Buggage | Photos By: Glenn Summers Like sand passing through an perceive as apathy on the part housing many residents of Class, Race and the LRA they fighting over who controls hourglass so goes the days of the of every level of government is public housing have voiced Race and class have been at the what when it should be just about lives of many New Orleanians; overflowing. While clearly some concerns about there right to center of the debate about what helping people?” where for many visible signs of progress has occurred; the return to the city. They see a happened in the city during and Months after the mayoral progress is an anomaly and the question becomes is it moving blind eye being turned to their after Hurricane Katrina. Jerome election, a bitter battle as Nagin road home seems one paved fast enough? plight as they’ve staged protests Booker, a displaced New Orleans pulled an upset victory against with obstacles and frustrations. in Iberville and more recently resident from the hollow shell of insurmountable odds, much One wouldn’t be hard pressed to A question of housing the still unoccupied St. -

Ladainian TOMLINSON

THE NEW LA STADIUM THE CHARGERS ARE BRINGING THE FIGHT TO INGLEWOOD. The new LA Stadium at Hollywood Park, home of your Los Angeles Chargers in 2020, will deliver a revolutionary football experience custom-designed for the LA fan. The new Los Angeles Stadium at Hollywood Park will have the first ever, completely covered, open-air stadium with a clear view of the sky. The campus will feature 25 acres of park providing rare and expansive open space in the center of LA. The 70,000-seat stadium will be the center of a vibrant mixed-use development, just 3 miles from LAX. The low-profile building will sit 100 feet below ground level. The video board will provide a 360-degree double-sided 4K digital display viewing experience. There will be several clubs within the stadium, all offering LA-inspired premium dining and private entrances. Many concourse and club spaces will have patios bathed in sunlight. Champions Plaza will host pregame activities and special events, and feature a 6,000-seat performance venue. Entry and exit will be easy, and there will be more than 10,500 parking spaces on site. For more information on becoming a 2020 LA Stadium Season Ticket Member, visit FightforLA.com II OWNERSHIP, COACHING AND ADMINISTRATION 20182018 THE NEW LA STADIUM CHARGERSSCHEDULESCHEDULEGOGO BOLTSBOLTS PRESEASON WEEK DATE OPPONENT TIME NETWORK THE CHARGERS ARE 1 Sat. Aug. 11 @ Cardinals 7:00 pm KABC BRINGING THE FIGHT 2 Sat. Aug. 18 SEAHAWKS 7:00 pm KABC 3 Sat. Aug. 25 SAINTS 5:00 pm CBS * TO INGLEWOOD. -

INDIANAPOLIS COLTS WEEKLY PRESS RELEASE Indiana Farm Bureau Football Center P.O

INDIANAPOLIS COLTS WEEKLY PRESS RELEASE Indiana Farm Bureau Football Center P.O. Box 535000 Indianapolis, IN 46253 www.colts.com REGULAR SEASON WEEK 6 INDIANAPOLIS COLTS (3-2) VS. NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS (4-0) 8:30 P.M. EDT | SUNDAY, OCT. 18, 2015 | LUCAS OIL STADIUM COLTS HOST DEFENDING SUPER BOWL BROADCAST INFORMATION CHAMPION NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS TV coverage: NBC The Indianapolis Colts will host the New England Play-by-Play: Al Michaels Patriots on Sunday Night Football on NBC. Color Analyst: Cris Collinsworth Game time is set for 8:30 p.m. at Lucas Oil Sta- dium. Sideline: Michele Tafoya Radio coverage: WFNI & WLHK The matchup will mark the 75th all-time meeting between the teams in the regular season, with Play-by-Play: Bob Lamey the Patriots holding a 46-28 advantage. Color Analyst: Jim Sorgi Sideline: Matt Taylor Last week, the Colts defeated the Texans, 27- 20, on Thursday Night Football in Houston. The Radio coverage: Westwood One Sports victory gave the Colts their 16th consecutive win Colts Wide Receiver within the AFC South Division, which set a new Play-by-Play: Kevin Kugler Andre Johnson NFL record and is currently the longest active Color Analyst: James Lofton streak in the league. Quarterback Matt Hasselbeck started for the second consecutive INDIANAPOLIS COLTS 2015 SCHEDULE week and completed 18-of-29 passes for 213 yards and two touch- downs. Indianapolis got off to a quick 13-0 lead after kicker Adam PRESEASON (1-3) Vinatieri connected on two field goals and wide receiver Andre John- Day Date Opponent TV Time/Result son caught a touchdown. -

The Fifth Down

Members get half off on June 2006 Vol. 44, No. 2 Outland book Inside this issue coming in fall The Football Writers Association of President’s Column America is extremely excited about the publication of 60 Years of the Outland, Page 2 which is a compilation of stories on the 59 players who have won the Outland Tro- phy since the award’s inception in 1946. Long-time FWAA member Gene Duf- Tony Barnhart and Dennis fey worked on the book for two years, in- Dodd collect awards terviewing most of the living winners, spin- ning their individual tales and recording Page 3 their thoughts on winning major-college football’s third oldest individual award. The 270-page book is expected to go on-sale this fall online at www.fwaa.com. All-America team checklist Order forms also will be included in the Football Hall of Fame, and 33 are in the 2006-07 FWAA Directory, which will be College Football Hall of Fame. Dr. Outland Pages 4-5 mailed to members in late August. also has been inducted posthumously into As part of the celebration of 60 years the prestigious Hall, raising the number to 34 “Outland Trophy Family members” to of Outland Trophy winners, FWAA mem- bers will be able to purchase the book at be so honored . half the retail price of $25.00. Seven Outland Trophy winners have Nagurski Award watch list Ever since the late Dr. John Outland been No. 1 picks overall in NFL Drafts deeded the award to the FWAA shortly over the years, while others have domi- Page 6 before his death, the Outland Trophy has nated college football and pursued greater honored the best interior linemen in col- heights in other areas upon graduation. -

1-1-17 at Los Angeles.Indd

WEEK 17 GAME RELEASE #AZvsLA Mark Dalton - Vice President, Media Relations Chris Melvin - Director, Media Relations Mike Helm - Manag er, Media Relations Matt Storey - Media Relations Coordinator Morgan Tholen - Media Relations Assistant ARIZONA CARDINALS (6-8-1) VS. LOS ANGELES RAMS (4-11) L.A. Memorial Coliseum | Jan. 1, 2017 | 2:25 PM THIS WEEK’S GAME ARIZONA CARDINALS - 2016 SCHEDULE The Cardinals conclude the 2016 season this week with a trip to Los Ange- Regular Season les to face the Rams at the LA Memorial Coliseum. It will be the Cardinals Date Opponent Loca on AZ Time fi rst road game against the Los Angeles Rams since 1994, when they met in Sep. 11 NEW ENGLAND+ Univ. of Phoenix Stadium L, 21-23 Anaheim in the season opener. Sep. 18 TAMPA BAY Univ. of Phoenix Stadium W, 40-7 Last week, Arizona defeated the Seahawks 34-31 at CenturyLink Field to im- Sep. 25 @ Buff alo New Era Field L, 18-33 prove its record to 6-8-1. The victory marked the Cardinals second straight Oct. 2 LOS ANGELES Univ. of Phoenix Stadium L, 13-17 win at Sea le and third in the last four years. QB Carson Palmer improved to 3-0 as Arizona’s star ng QB in Sea le. Oct. 6 @ San Francisco# Levi’s Stadium W, 33-21 Oct. 17 NY JETS^ Univ. of Phoenix Stadium W, 28-3 The Cardinals jumped out to a 14-0 lead a er Palmer connected with J.J. Oct. 23 SEATTLE+ Univ. of Phoenix Stadium T, 6-6 Nelson on an 80-yard TD pass in the second quarter and they held a 14-3 lead at the half. -

Houston Texans at New England Patriots

THURSDAY NIGHT NOTES: HOUSTON TEXANS AT NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS September 22, 2016 Week 3 begins on Thursday night with the New England Patriots hosting the Houston Texans (CBS, NFL Network, Twitter; 8:25 PM ET) at Gillette Stadium. The Patriots and Texans both enter Thursday’s matchup with 2-0 records. In Week 2, New England defeated Miami 31-24 while Houston topped Kansas City 19-12. The Patriots have won 27 of their past 29 games at home (including the postseason) and five of their past six regular-season contests against Houston. The Texans are aiming for their first 3-0 start since 2012. Houston head coach BILL O’BRIEN was an assistant under Patriots head coach BILL BELICHICK with New England from 2007-11. REGULAR SEASON SERIES TEXANS PATRIOTS SERIES LEADER 5-1 STREAKS Past 3 COACHES VS. OPP. Bill O’Brien: 0-1 Bill Belichick: 5-1 LAST WEEK W 19-12 vs. Kansas City W 31-24 vs. Miami LAST GAME 12/13/15: Patriots 27 at Texans 6. New England QB Tom Brady throws for 226 yards & 2 TDs. Patriots TE Rob Gronkowski has 4 catches for 87 yards & TD. LAST GAME AT SITE 12/10/12: Patriots 42, Texans 14. New England QB Tom Brady throws for 296 yards & 4 TDs. Patriots RB Stevan Ridley adds 72 rushing yards & TD. REFEREE Walt Coleman BROADCAST CBS/NFLN/Twitter (8:25 PM ET): Jim Nantz, Phil Simms and Tracy Wolfson (Field reporter). Westwood One: Ian Eagle, Tony Boselli. STATS PASSING Brock Osweiler: 41-68-499-3-3-79.2 Jacoby Brissett (R): 6-9-92-0-0-100.2 OR Jimmy Garoppolo: 42-60-498-4-0-117.2 RUSHING Lamar Miller: 53-189-3.6-0 LeGarrette Blount: 51-193-3.8-2 RECEIVING DeAndre Hopkins: 12-167-13.9-2 Julian Edelman: 14-142-10.1-0 OFFENSE 347.5 414.0 TAKE/GIVE +1 +1 DEFENSE 274.5 401.5 SACKS John Simon: 2.5 3 tied: 1 INTs Andre Hal: 1 Jamie Collins, Duron Harmon: 1 PUNTING Shane Lechler: 49.2 Ryan Allen: 36.2 KICKING Nick Novak: 24 (3/3 PAT; 7/8 FG) Stephen Gostkowski: 18 (6/6 PAT; 4/5 FG) NOTES TEXANS: Aim for 2nd 3-0 start in team history (2012)…Head coach BILL O’BRIEN was assistant with NE from 2007- 11…QB BROCK OSWEILER won only career start vs. -

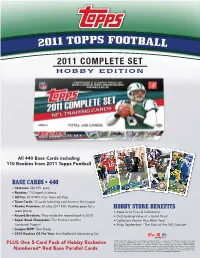

2011 Topps Football 2011 Complete Set Hobby Edition

2011 TOPPS FOOTBALL 2011 COMPLETE SET HOBBY EDITION All 440 Base Cards including 110 Rookies from 2011 Topps Football BASE CARDS • 440 • Veterans: 262 NFL pros. • Rookies: 110 hopeful talents. • All-Pro: 2010 NFL First Team All-Pros. • Team Cards: 32 cards featuring each team in the league. • Rookie Premiere: 30 elite 2011 NFL Rookies pose for a HOBBY STORE BENEFITS team photo. • Appeals to Fans & Collectors! • Record Breakers: They made the record book in 2010. • Outstanding Value at a Great Price! • Super Bowl Champions: The Packers and the • Collectors Return Year After Year! Lombardi Trophy! • Ships September - The Start of the NFL Season! • League MVP: Tom Brady • 2010 Rookies Of The Year: Sam Bradford & Ndamukong Suh ® TM & © 2011 The Topps Company, Inc. Topps and Topps Football are trademarks of The Topps Company, Inc. All rights reserved. © 2011 NFL Properties, LLC. Team Names/Logos/Indicia are trademarks of the teams indicated. All other PLUS One 5-Card Pack of Hobby Exclusive NFL-related trademarks are trademarks of the National Football League. Officially Licensed Product of NFL PLAYERS | NFLPLAYERS.COM. Please note that you must obtain the approval of the National Football League Properties in promotional materials that incorporate any marks, designs, logos, etc. of the National Football League or any of its teams, unless the Numbered* Red Base Parallel Cards material is merely an exact depiction of the authorized product you purchase from us. Topps does not, in any manner, make any representations as to whether its cards will attain any future value. NO PURCHASE NECESSARY. PLUS ONE 5-CARD PACK OF HOBBY EXCLUSIVE NUMBERED RED BASE PARALLEL CARDS 2011 COMPLETE SET CHECKLIST 1 Aaron Rodgers 69 Tyron Smith 137 Team Card 205 John Kuhn 273 LeGarrette Blount 341 Braylon Edwards 409 D.J. -

Giants Qb Eli Manning, Rams Dt Aaron Donald & Cardinals K

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 12/16/15 http://twitter.com/nfl345 GIANTS QB ELI MANNING, RAMS DT AARON DONALD & CARDINALS K CHANDLER CATANZARO NAMED NFC PLAYERS OF WEEK 14 Quarterback ELI MANNING of the New York Giants, defensive tackle AARON DONALD of the St. Louis Rams and kicker CHANDLER CATANZARO of the Arizona Cardinals are the NFC Offensive, Defensive and Special Teams Players of the Week for games played the 14th week of the 2015 season (December 10, 13-14), the NFL announced today. OFFENSE: QB ELI MANNING, NEW YORK GIANTS Manning completed 27 of 31 passes (career-high 87.1 percent) for 337 yards with four touchdowns and no interceptions for a career-best 151.5 passer rating in the Giants’ 31-24 win at Miami. Manning’s 87.1 completion percentage is the highest by a Giants quarterback in a regular-season game (minimum 20 attempts) and the second-best mark in franchise history behind PHIL SIMMS’ 88.0 completion percentage (22 of 25) in Super Bowl XXI. He is the first Giants quarterback to have a passer rating of at least 150 in a game since 2002 (KERRY COLLINS, 158.3 on December 22). Manning threw touchdown passes to ODELL BECKHAM JR. (84 and six yards), RUEBEN RANDLE (six yards) and WILL TYE (five yards). Manning’s 84-yard touchdown pass to Beckham with 11:13 remaining in the fourth quarter broke a 24-24 tie and proved to be the game-winning score. He has six touchdown passes of at least 50 yards this season, the most in the NFL. -

Weekly Release Vs December 8, 2016 5:25 P.M

WEEKLY RELEASE VS DECEMBER 8, 2016 5:25 P.M. PT | ARROWHEAD STADIUM OAKLAND RAIDERS WEEKLY RELEASE 1220 HARBOR BAY PARKWAY | ALAMEDA, CA 94502 | RAIDERS.COM WEEK 14 | DECEMBER 8, 2016 | 5:25 P.M. PT | ARROWHEAD STADIUM VS. 10-2 9-3 GAME PREVIEW THE SETTING The Oakland Raiders will travel on a short week to play a Date: Thursday, December 8, 2016 primetime divisional game against the Kansas City Chiefs at Ar- Kickoff: 5:25 p.m. PT rowhead Stadium on Thursday, Dec. 8 at 5:25 p.m. PT. Thursday’s Site: Arrowhead Stadium (1972) contest between the two long-time rivals pits the AFC West’s top Capacity/Surface: 79,541/Natural Grass two teams, with the Raiders leading the division at 10-2 and the Regular Season: Chiefs lead, 59-51-2 Chiefs in second at 9-3. The game begins a stretch run for the Postseason: Chiefs lead, 2-1 Raiders that sees them play three of their final four games on the road, with all three road games coming against AFC West oppo- nents. The game will be the final matchup between the Raiders and Chiefs this year, as the Chiefs won the first game in Oakland RAIDERS ON THE ROAD back in Week 6. Last week, Oakland earned a win at home, com- This season, the Raiders have come up big away from their home ing back from a 15-point deficit in to beat the Buffalo Bills, 38-24. stadium. In six games played away from Oakland (five road games Kansas City won a road game against the Atlanta Falcons, 29-28. -

Rams Patriots Rams Offense Rams Defense

New England Patriots vs Los Angeles Rams Sunday, February 03, 2019 at Mercedes-Benz Stadium RAMS RAMS OFFENSE RAMS DEFENSE PATRIOTS No Name Pos WR 83 J.Reynolds 11 K.Hodge DE 90 M.Brockers 94 J.Franklin No Name Pos 4 Zuerlein, Greg K TE 89 T.Higbee 81 G.Everett 82 J.Mundt NT 93 N.Suh 92 T.Smart 69 S.Joseph 2 Hoyer, Brian QB 6 Hekker, Johnny P 3 Gostkowski, Stephen K 11 Hodge, Khadarel WR LT 77 A.Whitworth 70 J.Noteboom DT 99 A.Donald 95 E.Westbrooks 6 Allen, Ryan P 12 Cooks, Brandin WR LG 76 R.Saffold 64 J.Demby WILL 56 D.Fowler 96 M.Longacre 45 O.Okoronkwo 11 Edelman, Julian WR 14 Mannion, Sean QB 12 Brady, Tom QB 16 Goff, Jared QB C 65 J.Sullivan 55 Br.Allen OLB 50 S.Ebukam 53 J.Lawler 49 T.Young 13 Dorsett, Phillip WR 17 Woods, Robert WR RG 66 A.Blythe ILB 58 C.Littleton 54 B.Hager 59 M.Kiser 15 Hogan, Chris WR 19 Natson, JoJo WR 18 Slater, Matt WR 20 Joyner, Lamarcus S RT 79 R.Havenstein ILB 26 M.Barron 52 R.Wilson 21 Harmon, Duron DB 21 Talib, Aqib CB WR 12 B.Cooks 19 J.Natson LCB 22 M.Peters 37 S.Shields 31 D.Williams 22 Melifonwu, Obi DB 22 Peters, Marcus CB 23 Chung, Patrick S 23 Robey, Nickell CB WR 17 R.Woods RCB 21 A.Talib 32 T.Hill 23 N.Robey 24 Gilmore, Stephon CB 24 Countess, Blake DB QB 16 J.Goff 14 S.Mannion SS 43 J.Johnson 24 B.Countess 26 Michel, Sony RB 26 Barron, Mark LB 27 Jackson, J.C. -

2011 GATORS in the NFL 35 Players, 429 Games Played, 271

2012 FLORIDA FOOTBALL TABLE OF CONTENTS 2012 SCHEDULE COACHES Roster All-Time Results September 2-3 Roster 107-114 Year-by-Year Scores 1 Bowling Green Gainesville, Fla. 115-116 Year-by-Year Records 8 at Texas A&M* College Station, Texas Coaching Staff 117 All-Time vs. Opponents 15 at Tennessee* Knoxville, Tenn. 4-7 Head Coach Will Muschamp 118-120 Series History vs. SEC, FSU, Miami 22 Kentucky* Gainesville, Fla. 10 Tim Davis (OL) 121-122 Ben Hill Griffin Stadium at Florida Field 29 Bye 11 D.J. Durkin (LB/Special Teams) 123-127 Miscellaneous History PLAYERS 12 Aubrey Hill (WR/Recruiting Coord.) 128-138 Bowl Game History October 13 Derek Lewis (TE) 6 LSU* Gainesville, Fla. 14 Brent Pease (Offensive Coord./QB) Record Book 13 at Vanderbilt* Nashville, Tenn. 15 Dan Quinn (Defensive Coord./DL) 139-140 Year-by-Year Stats 20 South Carolina* Gainesville, Fla. 16 Travaris Robinson (DB) 141-144 Yearly Leaders 27 vs. Georgia* Jacksonville, Fla. 17 Brian White (RB) 145 Bowl Records 18 Bryant Young (DL) 146-148 Rushing November 19 Jeff Dillman (Director of Strength & Cond.) 149-150 Passing 3 Missouri* Gainesville, Fla. 2011 RECAP 19 Support Staff 151-153 Receiving 10 UL-Lafayette (Homecoming) Gainesville, Fla. 154 Total Offense 17 Jacksonville State Gainesville, Fla. 2012 Florida Gators 155 Kicking 24 at Florida State Tallahassee, Fla. 20-45 Returning Player Bios 156 Returns, Scoring 46-48 2012 Signing Class 157 Punting December 158 Defense 1 SEC Championship Atlanta, Ga. 2011 Season Review 160 National and SEC Record Holders *Southeastern Conference Game HISTORY 49-58 Season Stats 161-164 Game Superlatives 59-65 Game-by-Game Review 165 UF Stat Champions 166 Team Records CREDITS Championship History 167 Season Bests The official 2012 University of Florida Football Media Guide has 66-68 National Championships 168-170 Miscellaneous Charts been published by the University Athletic Association, Inc. -

History and Records

HISTORY AND RECORDS YEAR -BY-YEAR CHAMPIONS DIVISIONAL CHAMPIONS (SINCE 1997) Mid-American Conference Champions West Division Champions 2015 NIU/Toledo/WMU/CMU (6-2) 2015 Bowling Green (7-1) ! 1967 Toledo (5-1) 2014 Northern Illinois (7-1) 2013 Northern Illinois (8-0) 2014 Northern Illinois (7-1) ! 1966 Miami (5-1) 2012 Northern Illinois (8-0) 2013 Bowling Green (7-1) ! 1965 Bowling Green/Miami (5-1) 2011 Northern Illinois/Toledo (7-1) 2010 Northern Illinois (8-0) 2012 Northern Illinois (8-0) ! 1964 Bowling Green (5-1) 2009 Central Michigan (8-0) 2008 Ball State (8-0) 2011 Northern Illinois (7-1) ! 1963 Ohio (5-1) 2007 C. Michigan/Ball State (4-1) 2010 Miami (7-1) ! 1962 Bowling Green (5-0-1) 2006 Central Michigan (7-1) 2005 NIU/UT (6-2) 2009 Central Michigan (8-0) ! 1961 Bowling Green (5-1) 2004 Toledo/NIU (7-1) 2008 Buffalo (5-3) ! 2003 Bowling Green (7-1) 1960 Ohio (6-0) 2002 Toledo/NIU (7-1) 2007 Central Michigan (7-1) ! 1959 Bowling Green (6-0) 2001 UT/NIU/BSU (4-1) 2000 WMU/Toledo (4-1) 2006 Central Michigan (7-1) ! 1958 Miami (5-0) 1999 WMU (6-2) 2005 Akron (5-3) ! 1957 Miami (5-0) 1998 Toledo (6-2) 1997 Toledo (7-1) 2004 Toledo (7-1) ! 1956 Bowling Green (5-0-1) East Division Champions 2003 Miami (8-0) ! 1955 Miami (5-0) 2015 Bowling Green (7-1) 2014 Bowling Green (5-3) 2002 Marshall (7-1) ! 1954 Miami (4-0) 2013 Bowling Green (7-1) 2001 Toledo (5-2) ! 1953 Ohio (5-0-1) 2012 Kent State (8-0) 2011 Ohio (6-2) 2000 Marshall (5-3) ! 1952 Cincinnati (3-0) 2010 Miami (7-1) 2009 Ohio/Temple (7-1) 1999 Marshall (8-0) ! 1951 Cincinnati