Credit Lines As Insurance: Evidence from Bangladesh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Present Status of Fish Biodiversity and Abundance in Shiba River, Bangladesh

Univ. J. zool. Rajshahi. Univ. Vol. 35, 2016, pp. 7-15 ISSN 1023-6104 http://journals.sfu.ca/bd/index.php/UJZRU © Rajshahi University Zoological Society Present status of fish biodiversity and abundance in Shiba river, Bangladesh D.A. Khanom, T Khatun, M.A.S. Jewel*, M.D. Hossain and M.M. Rahman Department of Fisheries, University of Rajshahi, Rajshahi 6205, Bangladesh Abstract: The study was conducted to investigate the abundance and present status of fish biodiversity in the Shiba river at Tanore Upazila of Rajshahi district, Bangladesh. The study was conducted from November, 2016 to February, 2017. A total of 30 species of fishes were recorded belonging to nine orders, 15 families and 26 genera. Cypriniformes and Siluriformes were the most diversified groups in terms of species. Among 30 species, nine species under the order Cypriniformes, nine species of Siluriformes, five species of Perciformes, two species of Channiformes, two species of Mastacembeliformes, one species of Beloniformes, one species of Clupeiformes, one species of Osteoglossiformes and one species of Decapoda, Crustacea were found. Machrobrachium lamarrei of the family Palaemonidae under Decapoda order was the most dominant species contributing 26.29% of the total catch. In the Shiba river only 6.65% threatened fish species were found, and among them 1.57% were endangered and 4.96% were vulnerable. The mean values of Shannon-Weaver diversity (H), Margalef’s richness (D) and Pielou’s (e) evenness were found as 1.86, 2.22 and 0.74, respectively. Relationship between Shannon-Weaver diversity index (H) and pollution indicates the river as light to moderate polluted. -

Socio-Economic and Livelihood Status of Fishermen Around the Atrai And

International Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Studies 2015; 2(6): 402-408 ISSN: 2347-5129 (ICV-Poland) Impact Value: 5.62 Socio-economic and livelihood status of fishermen (GIF) Impact Factor: 0.352 around the Atrai and Kankra Rivers of Chirirbandar IJFAS 2015; 2(6): 402-408 © 2015 IJFAS Upazila under Dinajpur District www.fisheriesjournal.com Received: 20-05-2015 Accepted: 23-06-2015 Salim Reza, Md. Sazzad Hossain, Ujjwal Hossain, Md. Abu Zafar Salim Reza Department of Aquaculture, Abstract Faculty of Fisheries, Bangladesh The study was conducted to investigate the socio-economic and livelihood status of the fishermen around Agricultural University, the Atrai and Kankra rivers at Chirirbandar Upazila, Dinajpur from October, 2013 to January 2014. Mymensingh-2202. Twenty five fishermen were randomly selected from the areas who were solely involved in fishing in the rivers. Several PRA tools were used to collect the data from the fishing communities such as, personal Md. Sazzad Hossain interview, crosscheck interview with extension agents, older persons, transect walk and case study. The Department of Aquaculture, data interpretations showed that 60% respondent’s primary occupation were fishing, majority of them Faculty of Fisheries, Bangladesh were middle age group (31-45 yrs) and mostly were landless or marginal land holders. All of the Agricultural University, respondents were male of which 84% were Muslims and rests were Hindus. About 88% fishermen were Mymensingh-2202. married and average size of middle household (56%) was more than the national average (4.4%). Ujjwal Hossain Moreover, 64% family was nuclear, 44% fishermen were illiterate and 36% can only sign. -

Environment and Fish Fauna of the Atrai River: Global and Local Conservation Perspective

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 24 March 2017 Version of attached le: Published Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Chaki, N. and Jahan, S. and Fahad, M.F.H. and Galib, S.M. and Mohsin, A.B.M. (2014) 'Environment and sh fauna of the Atrai River : global and local conservation perspective.', Journal of sheries., 2 (3). pp. 163-172. Further information on publisher's website: https://doi.org/10.17017/jsh.v2i3.2014.46 Publisher's copyright statement: c Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 3.0 License Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk Journal of Fisheries eISSN 2311-3111 Volume 2 Issue 3 Pages: 163-172 December 2014 pISSN 2311-729X Peer Reviewed | Open Access | Online First Original article DOI: dx.doi.org/10.17017/jfish.v2i3.2014.46 Environment and fish fauna of the Atrai River: global and local conservation perspective Nipa Chaki 1 Sayka Jahan 2 Md. -

Parameters Associated with Growth Factors of Five Fish Species in the Atrai River, TL Vs

Available online at www.banglajol.info Bangladesh J. Sci. Ind. Res. 53(2), 155-160, 2018 To estimate the condition (Fulton’s, CFf and relative body due to geographical variation but are within the limits for G. secluded from another species may be due to morphometrics Gupta BK, Sarkar UK, Bhardwaj SK and Pal A (2011), Le Cren ED (1951), The length-weight relationships and weight, BWr) and form (a3.0) factors, regression parameters a cenia (5.50-6.65 cm, Chaki et al., 2013), S. bacaila and body shape controlled by a number of environmental and Condition factor, length-weight and length-weight seasonal cycle in gonad weight and condition in the and b were obtained from previously calculated LWRs (log (3.40-15.20 cm, Masud and Singh, 2015) and S. phulo heredity factors (Cadrin, 2000) that were not measured during relationships of an endangered fish Ompok pabda perch (Perca fluviatilis), J Anim Ecol. 20: 201-219. Parameters associated with growth factors of five fish species in the Atrai River, TL vs. log BW) followed by Islam and Mia (2016). Where, the (6.00-10.70 cm and 1.36-7.21 g, Siddik et al., 2016), this study. (Hamilton 1822) (Silurifomes: Siluridae) from the DOI: 10.2307/1540 earlier values of a and b are noted as 0.010 and 2.899 for A. respectively. As there is a first record on length and body River Gomti, a tributary of the River Ganga, India, J Dinajpur, Bangladesh jaya, 0.006 and 3.059 for G. cenia, 0.012 and 3.004 for G. -

Suspended Sediment Transport in the Ganges-Brahmaputra

SUSPENDED SEDIMENT TRANSPORT IN THE GANGES-BRAHMAPUTRA RIVER SYSTEM, BANGLADESH A Thesis by STEPHANIE KIMBERLY RICE Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE August 2007 Major Subject: Oceanography SUSPENDED SEDIMENT TRANSPORT IN THE GANGES-BRAHMAPUTRA RIVER SYSTEM, BANGLADESH A Thesis by STEPHANIE KIMBERLY RICE Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Approved by: Co-Chairs of Committee, Beth L. Mullenbach Wilford D. Gardner Committee Members, Mary Jo Richardson Head of Department, Robert R. Stickney August 2007 Major Subject: Oceanography iii ABSTRACT Suspended Sediment Transport in the Ganges-Brahmaputra River System, Bangladesh. (August 2007) Stephanie Kimberly Rice, B.S., The University of Mississippi Co-Chairs of Advisory Committee: Dr. Beth L. Mullenbach Dr. Wilford D. Gardner An examination of suspended sediment concentrations throughout the Ganges- Brahmaputra River System was conducted to assess the spatial variability of river sediment in the world’s largest sediment dispersal system. During the high-discharge monsoon season, suspended sediment concentrations vary widely throughout different geomorphological classes of rivers (main river channels, tributaries, and distributaries). An analysis of the sediment loads in these classes indicates that 7% of the suspended load in the system is diverted from the Ganges and Ganges-Brahmaputra rivers into southern distributaries. Suspended sediment concentrations are also used to calculate annual suspended sediment loads of the main river channels. These calculations show that the Ganges carries 262 million tons/year and the Brahmaputra carries 387 million tons/year. -

Download the Full Paper

Int. J. Biosci. 2021 International Journal of Biosciences | IJB | ISSN: 2220-6655 (Print) 2222-5234 (Online) http://www.innspub.net Vol. 18, No. 4, p. 164-172, 2021 RESEARCH PAPER OPEN ACCESS Livelihood status and vulnerabilities of small scale Fishermen around the Padma River of Rajshahi District Rubaiya Pervin*1, Mousumi Sarker Chhanda2, Sabina Yeasmin1, Kaniz Fatema1, Nipa Gupta2 1Department of Fisheries Management, Hajee Mohammad Danesh Science and Technology University, Dinajpur, Bangladesh 2Depatment of Aquaculture, Hajee Mohammad Danesh Science and Technology University, Dinajpur, Bangladesh Key words: Padma River, Livelihood status, Fishermen, Constraints, Suggestions http://dx.doi.org/10.12692/ijb/18.4.164-172 Article published on April 30, 2021 Abstract The investigation was conducted on the livelihood status of small scale fishermen around the Padma river in Rajshahi district from July 2016 to February 2017. Hundred fishermen were surveyed randomly with a structured questionnaire. The livelihood status of fishermen was studied in terms of age, family, occupation, education, housing and health condition, credit and income. It was found that most of the fishermen were belonged to the age groups of 20-35 years (50%) represented by 85% Muslims. Majority of them (62%) lived in joint family and average household size was 6-7 people. Educational status revealed that 66% were illiterate. Fishermen houses were found to be of two types namely semi-constructed and unconstructed and among them 77% houses were connected with electricity. About 85% fishermen were landless represented by 95% rearing livestock. Regarding health and sanitation 85% fishermen used sanitary latrines. About 83% fishermen were solely depends on fishing and annual income of 50% fishermen was 50,000 to 60,000 TK. -

A Study of Social Justice and Development of Rajwar in Barind Region

A Study of Social Justice and development of Rajwar in Barind region M.Phil Thesis Researcher Hosne-Ara-Afroz A Dissertation Submitted to the Department of Anthropology, University of Dhaka for the degree of Master of Philosophy in Anthropology Department of Anthropology University of Dhaka June, 2016 A Study of Social Justice and development of Rajwar in Barind region M.Phil Thesis Researcher Hosne-Ara-Afroz Department of Anthropology University of Dhaka. June, 2016 A Study of Social Justice and development of Rajwar in Barind region M.Phil Thesis Researcher Hosne-Ara-Afroz Master of Philosophy in Anthropology University of Dhaka Department of Anthropology University of Dhaka Supervisor Dr. Md. Ahsan Ali Professor Department of Anthropology University of Dhaka Department of Anthropology University of Dhaka June, 2016 DECLARATION I do hereby declare that, I have written this M.phil thesis myself, it is an original work and that it has not been submitted to any other University for a degree. No part of it, in any form, has been published in any book or journal. Hosne-Ara- Afroz M.phil. Fellow Department of Anthropology University of Dhaka. June 2016 Page | i ‡dvb t (Awdm) 9661900-59/6688 Phone: (off.) 9661900-59-6688 b„weÁvbwefvM Fax: 880-2-8615583 E-mail: 1) [email protected] XvKvwek¦we`¨vjq 2) [email protected] XvKv-1000, evsjv‡`k DEPARTMENT OF ZvwiL ANTHROPOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF DHAKA DHAKA-1000,BANGLADESH Date: 29/06/2016 CERTIFICATE I do hereby certify that Hosne-Ara-Afroz, my M.phil supervisee has written this M.phil thesis herself, it is an original work and that it has not been submitted to any other university for a degree. -

Comparative Physiography of the Lower Ganges and Lower Mississippi Valleys

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1955 Comparative Physiography of the Lower Ganges and Lower Mississippi Valleys. S. Ali ibne hamid Rizvi Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Rizvi, S. Ali ibne hamid, "Comparative Physiography of the Lower Ganges and Lower Mississippi Valleys." (1955). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 109. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/109 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMPARATIVE PHYSIOGRAPHY OF THE LOWER GANGES AND LOWER MISSISSIPPI VALLEYS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Geography ^ by 9. Ali IJt**Hr Rizvi B*. A., Muslim University, l9Mf M. A*, Muslim University, 191*6 M. A., Muslim University, 191*6 May, 1955 EXAMINATION AND THESIS REPORT Candidate: ^ A li X. H. R iz v i Major Field: G eography Title of Thesis: Comparison Between Lower Mississippi and Lower Ganges* Brahmaputra Valleys Approved: Major Prj for And Chairman Dean of Gri ualc School EXAMINING COMMITTEE: 2m ----------- - m t o R ^ / q Date of Examination: ACKNOWLEDGMENT The author wishes to tender his sincere gratitude to Dr. Richard J. Russell for his direction and supervision of the work at every stage; to Dr. -

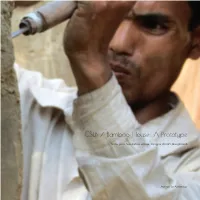

CSEB / Bamboo House: a Prototype

CSEB / Bamboo House: A Prototype Nobu para, Sundarban village, Dinajpur district, Bangladesh Author: Jo Ashbridge CSEB / Bamboo House: A Prototype Nobu para, Sundarban village, Dinajpur district, Bangladesh PRINTED BY Bob Books Ltd. 241a Portobello Road, London, W11 1LT, United Kingdom +44 (0)844 880 6800 First printed: 2014 (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0 Material in this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted, but acknowledgement is requested, together with a reference to the document number. A copy of the publication containing the quotation or reprint should be sent to Jo Ashbridge, [email protected] All content has been created by the author unless otherwise stated. Author: Jo Ashbridge Photographers: Jo Ashbridge / Philippa Battye / Pilvi Halttunen CSEB / Bamboo House: A Prototype Nobu para, Sundarban village, Dinajpur district, Bangladesh Funding Financial support for the research project was made possible by the RIBA Boyd Auger Scholarship 2012. In 2007, Mrs Margot Auger donated a sum of money to the RIBA in memory of her late husband, architect and civil engineer Boyd Auger. The Scholarship was first awarded in 2008 and has funded eight talented students since. The opportunity honours Boyd Auger’s belief that architects learn as they travel and, as such, it supports young people who wish to undertake imaginative and original research during periods -

Research Environmental Flow Assessment for the Main Rivers of the North-West Zone of Bangladesh

Contents lists available at Journal homepage: http://twasp.info/journal/home Research Environmental Flow Assessment for the Main Rivers of the North-West Zone of Bangladesh Afeefa Rahman1, Chiranjib Roy2*, Ashequr Rahman2, Fahad Jamil2, Md. Shariful Islam3 1Department of Water Resources Engineering, Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology, Dhaka, Bangladesh 2Department of Civil Engineering, University of Asia Pacific, Dhaka, Bangladesh 3Department of Civil Engineering, Rajshahi University of Engineering and Technology, Bangladesh *Corresponding Author : C Roy Email: [email protected] Published online : 12 March, 2019 Abstract:This research work has been carried out to assess the e-flow of the Padma, Jamuna, Teesta and Atrai. The first objective of this study is to identify the methodology among the established environment flow measurement techniques for these rivers in order to assess the flow-demand for fisheries, navigation as well as conspicuously maintenance of Sundarbans ecosystem. However, The main objective of this study is to observe the environmental flow assessment in a balanced and systematic way by the hydrological method to documentation on the subject, to examine its physical and numerical concepts and to trace the most recent trends in environmental flow assessment related research including the emerging interactions of hydrological methods with flow of water and other related fields. In this study, these observations have been accomplished mainly based on the Hydrological Method consisting of four distinct approaches. Moreover, the Flow Duration Curve analysis has also been adopted in order to get better understanding about the E- flow of the subjective rivers in the north-west zone of Bangladesh. Based on the study, the overall analysis reveals that the Padma river demands1083 m3/s of mean annual flow during January, February and March and 21676 m3/s of mean annual flow demands during August and September in Bangladesh. -

Credit Lines As Insurance: Evidence from Bangladesh

Credit Lines as Insurance: Evidence from Bangladesh Gregory Lane∗ October 1, 2018 [JOB MARKET PAPER] (Click here for the latest version) Abstract When insurance markets are absent, theory suggests that households can use credit lines to insure them- selves against adverse income shocks. However, in many developing countries access to credit in the aftermath of shocks is scarce as negatively affected households are frequently denied loans. In this paper I test whether a new financial product that offers guaranteed credit access after a shock, allows household to insure them- selves against risk. To this end, I run a large scale RCT in Bangladesh with one of the country's largest microcredit institutions. Microfinance clients were randomly pre-approved for loans that are made avail- able in the event of local flooding. I show that this unique type of microcredit improves household welfare through two channels: an ex-ante insurance effect where households increase investment in risky production and an ex-post effect where households are better able to maintain consumption and asset levels after a shock. I also document that households value this product, taking costly action to preserve their guaranteed access. Importantly, extension of this additional credit improves loan repayment rates and MFI profitability, suggesting that this product can be sustainably extended to households already connected to microcredit networks. ∗Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, UC Berkeley. Email: [email protected] gratefully acknowledge the financial support of BASIS and Feed the Future. I would like to thank my partner BRAC for their collaboration, and in particular Hitoishi Chakma, Monirul Hoque, and Faiza Farah Tuba for their invaluable assistance. -

A Checklist of Fish Species from Three Rivers in Northwestern Bangladesh Based on a Seven-Year Survey

PLATINUM The Journal of Threatened Taxa (JoTT) is dedicated to building evidence for conservaton globally by publishing peer-reviewed artcles online OPEN ACCESS every month at a reasonably rapid rate at www.threatenedtaxa.org. All artcles published in JoTT are registered under Creatve Commons Atributon 4.0 Internatonal License unless otherwise mentoned. JoTT allows allows unrestricted use, reproducton, and distributon of artcles in any medium by providing adequate credit to the author(s) and the source of publicaton. Journal of Threatened Taxa Building evidence for conservaton globally www.threatenedtaxa.org ISSN 0974-7907 (Online) | ISSN 0974-7893 (Print) Short Communication A checklist of fish species from three rivers in northwestern Bangladesh based on a seven-year survey Imran Parvez, Mohammad Ashraful Alam, Mohammad Mahbubul Hassan, Yeasmin Ara, Imran Hoshan & Abu Syed Mohammad Kibria 26 April 2019 | Vol. 11 | No. 6 | Pages: 13786–13794 DOI: 10.11609/jot.4303.11.6.13786-13794 For Focus, Scope, Aims, Policies, and Guidelines visit htps://threatenedtaxa.org/index.php/JoTT/about/editorialPolicies#custom-0 For Artcle Submission Guidelines, visit htps://threatenedtaxa.org/index.php/JoTT/about/submissions#onlineSubmissions For Policies against Scientfc Misconduct, visit htps://threatenedtaxa.org/index.php/JoTT/about/editorialPolicies#custom-2 For reprints, contact <[email protected]> The opinions expressed by the authors do not refect the views of the Journal of Threatened Taxa, Wildlife Informaton Liaison Development Society, Zoo Outreach Organizaton, or any of the partners. The journal, the publisher, the host, and the part- Publisher & Host ners are not responsible for the accuracy of the politcal boundaries shown in the maps by the authors.