BROSELEY LOCAL HISTORY SOCIETY Journal No. 32 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ACTON SCOTT St Margaret Diocese of Hereford SO45368943

ACTON SCOTT St Margaret Diocese of Hereford SO45368943 There are no fewer than 6 ancient or veteran yews among the 13 that grow here. They form a cluster (numbers 5 to 10) at the west end of the churchyard. The majority of these older trees appeared to be male. Photos and girths are from 2012. Tree 5 is multi-stemmed from a short bole. It is only when viewed from the farmyard below that its size can be appreciated, with a root system that reaches the ground at the base of an 8' high wall. It was not possible to measure this tree. Tree 6 grows on the left side of the gate leading from the church- yard to the farmyard. Inclusion of the almost separated branch growing at the edge of the bole would create a girth of 26/28'. Excluding it gives a girth closer to 22'. The photo on the left shows the tree’s vast root system seen from the farmyard below. Tree 7 (left) grows on the right side of the gate. It is a solid tree, with a girth of approximately 17'. Tree 8 is the only yew that does not mark the churchyard perimeter. It is an ancient hollow tree with fine internal stems. Girth was 20' 4'' at 1', but it has been larger. It is the only tree singled out in The King’s England c1938 where Mee wrote that ‘among the fine yews in the churchyard is a grand veteran 21' round out-topping the massive 13th century tower’. It is seen here in 1998 (left) and 2012 (right). -

De Quincey Fields

De Quincey Fields A prestigious development of three, four and five bedroom homes in the picturesque village of Upton Magna www.shropshire-homes.com De Quincey Fields Located on the edge of the picturesque village of Upton Magna, De Quincey Fields is a development of 31 family homes, ranging from the exclusive Vanburgh on a plot of almost half an acre to the cottage style Corndon. Twenty-one of these homes are being offered for sale, the remainder are being retained by the Sundorne Estate and will be rented to local people. Upton Magna has a history dating back to the Domesday Book. It combines a wealth of attractive architecture and a superb rural location with easy access to Shrewsbury and Telford. The village has a thriving community based around a successful primary school, St Lucia’s Parish Church, a village pub and restaurant, and a busy village hall. It is close to Haughmond Hill, Haughmond Abbey and Attingham Park, all offering opportunities for recreation and leisure. All homes at De Quincey Fields are available to purchase with assistance from Help to Help Buy. This may enable many purchasers to benefit from a 20% Shared Equity Loan and to Buy purchase a new home with a 5% deposit. Please ask our Sales Negotiator for details. Image: Tim Ward Shropshire Homes is a local company with a well-deserved reputation for creating quality homes in keeping with their environment. The company has an impressive range of prestigious and sensitive projects to its credit and has won awards from the Royal Town Planning Institute, Shrewsbury & Atcham Borough Council and Shrewsbury Civic Society, along with titles in the British Housebuilder of the Year Awards. -

2013 Parish Plan.Indd

Withington Parish Plan 2013 1 Contents 3 Introduction 4 Review of 2008/9 Parish Plan 5 2013 Parish Plan objectives 6 Analysis of 2013 Parish Plan questionnaire 8 A brief history of Withington 12 Index of parish properties and map 14 The Countryside Code 15 Rights of Way 16 Village amenities and contacts 2 The Withington Parish Plan 2013 The Withington Parish Five Year Plan was first published in 2003 then revised and re- published in July 2008 and has now been updated in 2013. The Parish Plan is an important document as it states the views of the residents of Withington Parish and its future direction. It also feeds directly into the Shrewsbury Area Place Plan, which is used by Shropshire Council Departments when reviewing requirements for such projects as road improvement, housing and commercial planning, water and sewerage. This updated plan was produced by analysing answers to the questionnaire distributed to each household in March 2013. Of the 91 questionnaires distributed, 59 were completed and returned. The Shropshire Rural Community Council (RCC) carried out an independent analysis of the results using computer software specifically designed for this purpose. The Parish Plan is also published on the Withington website www.withingtonshropshire.co.uk 3 Withington 2008 Parish Plan: Review of progress Progress was determined by asking Parishioners to indicate their level of satisfaction as to whether the 8 objectives contained in the 2008 Parish Plan had been achieved (see table below) OBJECTIVE ACHIEVEMENTS HOUSING AND Oppose any further housing or commer- • All housing/commercial development applications have COMMERCIAL cial development. -

The Marches Evidence Base for VES 2019

THE MARCHES EVIDENCE BASE APRIL 2019 BLUE SAIL THE MARCHES EVIDENCE BASE APRIL 2019 CONTENTS 1 ABOUT THIS PAPER .................................................................................. 3 2 VOLUME & VALUE ................................................................................... 4 3 THE ACCOMMODATION OFFER ................................................................ 9 4 VISITOR ATTRACTIONS ........................................................................... 15 5 FESTIVALS AND EVENTS ......................................................................... 17 6 CULTURAL OFFER ................................................................................... 22 7 ACTIVITIES ............................................................................................. 29 2 BLUE SAIL THE MARCHES EVIDENCE BASE APRIL 2019 1 ABOUT THIS PAPER This paper sets out the key data and information used to inform the Visitor Economy Strategy. It looks at the information provided to us by the client group and additional desk research undertaken by Blue Sail. This paper is a snapshot in time. The Marches needs to separately establish and maintain a base of core data and information to benchmark performance. Where data collected by different local authorities uses different methodologies and/or relates to different years, we’ve looked at third party sources, e.g. Visit Britain, to enable us to provide a Marches-wide picture, to compare like with like and to illustrate how the Marches compares. 3 BLUE SAIL THE MARCHES EVIDENCE -

4 Forum Descriptions 2014

Shropshire Voluntary and Community Sector Assembly Forums of Interest Shropshire Housing Support Forum The Housing Support Forum is set up to provide an arena for discussing housing related support issues for both providers, clients and voluntary/statutory services. It acts as a collective voice for housing support in Shropshire. The Forum shares areas of concern, good working practices, information on emerging legislation and new areas of work. The Forum plays an important role in helping to shape service delivery in Shropshire. The five main aims of the Forum are: To protect and promote our service users interests, rights, and involvement. To promote collaborative and partnership working between Providers. To promote collaborative working with other voluntary agencies and statutory services. To promote best practice in the delivery of the service. To promote high standards and encourage all providers to contribute to a continuous improvement to Shropshire housing support services The forum meets 4 times a year in Shrewsbury. Membership is open to all providers of housing related support, partner agencies and representatives from service user groups. This includes small charities up to big national housing support providers. There are usually between 20-25 representatives at any one meeting. For information about the Shropshire Housing Support Forum please email Hilary Paddock at: [email protected] Shropshire Community Transport Consortium The Shropshire Community Transport Consortium was formed in November 2004 as a medium for Community Transport Operators to share information, discuss pertinent issues affecting them and their service users and to allow them to collectively promote Community Transport in Shropshire. In 2008 the Consortium agreed to become a Forum on Interest of the Voluntary and Community Sector Assembly (VCSA). -

Shropshire's Churchyard Yews

’CHURCHYARD YEWS painted by Rev. Edward Williams M.A. more than two hundred years ago photographs by Tim Hills between 1997 and 2012 Between 1786 and 1791 Rev. Edward Williams made a record of most of ’parish churches. He was described in The Gentlem’ magazine vol 153 as “ excellent ” who had also “much of ” We are told in The annals and magazine of natural history, zoology and botany - vol 1 p183 that his studies included “ catalogue of all the plants which he had detected during many years' careful herborization of the county of ”for which “accuracy is well known, and perfect reli- ance can be placed on any plant which he ” Williams work thus gives us a rare opportunity to see some of Shropshir’churchyard yew trees as they appeared two hundred and twenty years ago. The examples below give us reason to be confident in the accuracy of his recording. The yew at Boningale (left) now has a girth of about 13ft, while that at Bucknell (centre) now has a girth of about 19ft, and the Norbury giant (right) has a girth above 33ft. His attention to detail is illustrated in this example at Tasley. In the painting we can clearly see that sections of the bole are leaning outwards, a process which has led to the distinctive yew we see today. On the following pages, 28 of the yews in ’paintings are seen as they appeared two hundred and twenty years ago and at they are now. We are grateful to Shropshire Archives for granting us permission to use their material in this way. -

Notice of Election Double Column

NOTICE OF ELECTION Shropshire Council Election of Parish Councillors for the Parish listed below Number of Parish Councillors Parish to be elected Upton Magna Parish Council Seven 1. Forms of nomination for the above election may be obtained from the Clerk to the Parish Council, or the Returning Officer, at The Shirehall, Abbey Foregate, Shrewsbury, SY2 6ND, who will, at the request of an elector for any electoral area, prepare a nomination paper for signature. 2. Nomination papers must be hand-delivered to the Returning Officer, Shirehall, Abbey Foregate, Shrewsbury, Shropshire, SY2 6ND on any day after the date of this notice, but no later than 4 pm on Tuesday, 4th April 2017. Alternatively, candidates may submit their nomination papers at the following locations on specified dates, between the time shown below:- SHREWSBURY Bridgnorth Room, The Shirehall, Abbey Foregate, Shrewsbury - 9.00am to 5.00pm On Tuesday 14th March, Wednesday 15th March, Friday 17th March, Monday 20th March, Tuesday 21st March, Thursday 23rd March, Friday 24th March, Monday 27th March, Tuesday 28th March, Wednesday 29th March and Friday 31st March. - 9.00am to 7.00pm On Thursday 16th March, Wednesday 22nd March, Thursday 30th March and Monday 3rd April. - 9.00am to 4.00pm On Tuesday 4th April. OSWESTRY Council Chamber, Castle View - 8.45am to 6.00pm On Tuesday 14th March and Thursday 23rd March. - 8.45am to 5.30pm On Wednesday 29th March. WEM Edinburgh House, New Street - 9.15am to 4.30pm On Wednesday 15th March, Monday 20th March and Thursday 30th March. LUDLOW Helena Lane Day Care Centre - 8.45am to 4.00pm On Thursday 16th March and Wednesday 22nd March. -

Rural Settlement List 2014

National Non Domestic Rates RURAL SETTLEMENT LIST 2014 1 1. Background Legislation With effect from 1st April 1998, the Local Government Finance and Rating Act 1997 introduced a scheme of mandatory rate relief for certain kinds of hereditament situated in ‘rural settlements’. A ‘rural settlement’ is defined as a settlement that has a population of not more than 3,000 on 31st December immediately before the chargeable year in question. The Non-Domestic Rating (Rural Settlements) (England) (Amendment) Order 2009 (S.I. 2009/3176) prescribes the following hereditaments as being eligible with effect from 1st April 2010:- Sole food shop within a rural settlement and has a RV of less than £8,500; Sole general store within a rural settlement and has a RV of less than £8,500; Sole post office within a rural settlement and has a RV of less than £8,500; Sole public house within a rural settlement and has a RV of less than £12,500; Sole petrol filling station within a rural settlement and has a RV of less than £12,500; Section 47 of the Local Government Finance Act 1988 provides that a billing authority may grant discretionary relief for hereditaments to which mandatory relief applies, and additionally to any hereditament within a rural settlement which is used for purposes which are of benefit to the local community. Sections 42A and 42B of Schedule 1 of the Local Government and Rating Act 1997 dictate that each Billing Authority must prepare and maintain a Rural Settlement List, which is to identify any settlements which:- a) Are wholly or partly within the authority’s area; b) Appear to have a population of not more than 3,000 on 31st December immediately before the chargeable financial year in question; and c) Are, in that financial year, wholly or partly, within an area designated for the purpose. -

Chairman's Letter

CHAIRMAN’S LETTER Dear Members Welcome to the Shropshire Centre Caravan and Motorhome Club in this my 3rd year as Chairman. I look forward to continuing in my role and working with our new and growing committee and hope to see as many of you as possible on the rally field soon. I have been caravanning for a few years now along with my wife Michelle and my children Charlotte and Alfie and now our new addition Bailey our Cockapoo Puppy. Rallying is a great way to have a great family holiday and relax, meet new people and see parts of the countryside you would never normally visit. A caravan rally is just a temporary site for the weekend with friends. With or without electricity, you can have a great time in your caravan away from the grid. Just ask us and any of our regular ralliers, you can survive without being fully connected to the grid. My family and I look forward to meeting you and if you haven’t rallied before and have any concerns, just come and see us on one of our rallies, either with or without your van, just to see what it’s all about. A great way to meet new friends and catch up with old ones. See you soon Mark Lloyd Chairman CHAIRMAN’S CHARITY 2019 During the year we will once again be collecting donations for Troop Aid. When service personnel are injured either on training exercise or in combat they return to the United Kingdom without their personal effects or clothing. -

SHROPSHIRE. (&ELLY's Widows, Being the Interest of £Roo

~54 TUGFORD,.. SHROPSHIRE. (&ELLY's widows, being the interest of £roo. Captain Charles Bald- Office), via Munslow. The nearest money order offices wyn Childe J.P. of Kinlet Hall is lord m the manor of the are at Munslow & Church Stretton & telegraph office at entire parish and sole landowner. The soil is red clay; the Church Stretton. WALL LETTER Box in Rectory wall, subsoil varies from sandstone to gravel. The chief crops cleared at 3,40 p.m. week days only are wheat, barley, oats and turnips. The acreage is 1,312; CARRIER.-Maddox, from Bauldon, passes through to Lud- rateable value, £1,461 ; the population in 1881 was no, low on mon. & Bridgnorth on sat BAUCOT is a township I mile west. Parish Clerk, Samuel Jones. The children of this parish attend the schools at Munslow & Letters are received through Craven .Arms (Railway Sub- Abdon Farmer Nathaniel, farmer 1 Wall George, farmer & miller (water) Tugford. Gwilt Thomas, farmer Woodhoose Rev. Richard B.A. Rectory Jones Saml. blacksmith&; parish clerk Baucot.. Dodson William, wheelwright, Balaam's Morris John, farmer Marsh Thomas, farmer & overseer heath Price William, shopkeeper ShirleyJane (Mrs.)&; Richd.Wm.farmrs UFFINGTON is a parish and village, pleasantly seated canopies, and a timber ceiling of the 14th century: the 3 miles east from Shrewsbury and 2! miles north-west from most perfect portion now left is the infirmary hall, with a Upton Magna station on the Great Western and London and turreted western gable on the south side of the base court; North Western joint line from Shrewsbury -

About the Cycle Rides

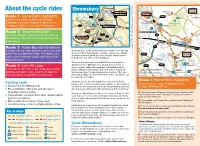

Sundorne Harlescott Route 45 Rodington About the cycle rides Shrewsbury Sundorne Mercian Way Heath Haughmond to Whitchurch START Route 1 Abbey START Route 2 START Route 1 Home Farm Highlights B5067 A49 B5067 Castlefields Somerwood Rodington Route 81 Gentle route following Route 81 through Monkmoor Uffington and Upton Magna to Home Farm, A518 Pimley Manor Haughmond B4386 Hill River Attingham. Option to extend to Rodington. Town Centre START Route 3 Uffington Roden Kingsland Withington Route 2 Around Attingham Route 44 SHREWSBURY This ride combines some places of interest in Route 32 A49 START Route 4 Sutton A458 Route 81 Shrewsbury with visits to Attingham Park and B4380 Meole Brace to Wellington A49 Home Farm. A5 Upton Magna A5 River Tern Walcot Route 3 Acton Burnell Adventure © Crown copyright and database rights 2012 Ordnance Survey 100049049 A5 A longer ride for more experienced cyclists with Shrewsbury is a very attractive historic market town nestled in a loop of the River Severn. The town centre has a largely Berwick Route 45 great views of Wenlock Edge, The Wrekin and A5064 Mercian Way You are not permitted to copy, sub-licence, distribute or sell any of this data third parties in form unaltered medieval street plan and features several timber River Severn Wharf to Coalport B4394 visits to Acton Burnell Castle and Venus Pool framed 15th and 16th century buildings. Emstrey Nature Reserve Home Farm The town was founded around 800AD and has played a B4380 significant role in British history, having been the site of A458 Attingham Park Uckington Route 4 Lyth Hill Loop many conflicts, particularly between the English and the A rewarding ride, with a few challenging climbs Welsh. -

National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act, 1949

10316 THE LONDON GAZETTE, 18TH SEPTEMBER 1970 Register Unit No. Name of Common Rural District CL 80 Stapeley Common (a) (b) Clun and Bishop's Castle. 81 Batchcott Common (a) (c) Ludlow. 82 The Recreation Ground and Allotments, Norbury (a) (b) ... Clun and Bishop's Castle. 83 War Memorial, Albrighton (a) Shifnal. 84 Wyre Common (a) (b) (c) ... ... Bridgnorth. 85 The Common, Hungry Hatton (a) (b) ... ... ... ... Market Dray ton. 86 Land at Hungry Hatton (a) (b) ... ... ... ... ... Market Dray ton. 87 Marl Hole, Lockley Wood (a) Market Drayton. 88 Lightwood Coppice (a) ... ... ... Market Drayton. 89 Hope Bowdler Hill (a) (b) Ludlow. 90 The Recreation Ground and Garden Allotment, Chelmarsh (a) Bridgnorth. 91 Baveny Wood Common (a) ... ... Bridgnorth. 92 Old Quarry, Stanton Lacy (a) ... ... Ludlow. 93 Clenchacre, Brosd'ey (a) ... ... Brignorth. 94 The Grove, Bridgnorth (a) (c) Brignorth. 95 The Knapps (a) ... ... ... ... ... Atcham. 96 Cramer Gutter (a) (6) ... ... Bridgnorth. 97 The Quabbs (a) (&) Clun and Bishop's Castle. 98 Gospel Oak (a) ... Wellington. 99 The Pound, Much Wenlock (a) Bridgnorth. 100 Land opposite Mount Bradford, St. Martins (a) ... Oswestry. 101 The Tumps (a) North Shropshire. 102 Homer Common (a) (c) ... ... ... ... Bridgnorth. 103 Ragleth Hill (a) (b) Ludlow. 104 Old Pinfold, Hordley (a) ' North Shropshire. 105 Land at Little Ness (a) ... Atcham. 106 Gravel Hole, Dudleston (a) ... ... ... North Shropshire. 107 The Turbary, Dudleston (a) ... ... ... ... ... North Shropshire. 108 The Turbary, Dudleston (a) North Shropshire. 109 Part O.S. No. 252, Longmynd (a) (6) Clun and Bishop's Castle. 110 The Moss, Lower Hopton (a) ... ... ... ... ... Atcham. 111 Henley Common (Part) (a) ... ... ... ... Ludlow. 2. Register of Town or Village Greens Register Unit No.