Edinburgh Research Explorer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PATTO – the JOHN HALSEY INTERVIEW

PATTO – the JOHN HALSEY INTERVIEW Patto, apart from being one of the finest (purely subjective, of course) bands this country ever produced, were not blessed with good fortune. Forever on the verge of making it really big, they broke up after six years of knocking on the door and finding no-one home. Subsequently, two of their number died while the other two were involved in a terrible car smash which left one with severe physical injuries and the other with severe mental problems. Drummer John Halsey is now the only Patto member who could possible give us an interview. Mike Patto and Ollie Halsall are both gone, while bassist Clive Griffiths apparently doesn't even recall being in a band! Despite bearing the scars of the accident (Halsey walks with a pronounced limp), John was only too pleased to submit to a Terrascopic grilling - an interview which took place in the wonderful Suffolk pub he runs with his wife Elaine. Bancroft and I spent a lovely afternoon and evening with the Halseys, B & B'd in the shadow of a 12th Century church cupboard and returned to London the next morning with one of the most enjoyable interviews either of us has ever done. John Halsey: I started playing drums because two mates who lived in my road in North Finchley (N. London), where I'm from, wanted to form a group. This was years and years ago, 1958, 1959. Want to see the photo? PT: Oh, look at that! 1959! Me, with a microphone inside me guitar that used to go out through me Mum's tape recorder, and if you put 'Record' and 'Play' on together, it'd act like an amplifier. -

The Moody Blues at Ironstone Amphitheatre | Murphys, California | 6/18/2017 (Concert Review + Photos)

7/5/2017 The Moody Blues at Ironstone Amphitheatre | Murphys, California | 6/18/2017 (Concert Review + Photos) The Moody Blues at Ironstone Amphitheatre | Murphys, California | 6/18/2017 (Concert Review + Photos) JUNE 20, 2017 BY JASON DEBORD Fans of The Moody Blues got to experience the band like never before on Sunday night at Ironstone Amphitheatre.c Featuring “an evening with…” style concert presentation, The Moody Blues played two full sets in front of the massive crowd in attendance, the Úrst with various hits from their career and the second presenting a track by track playing of every songs from their groundbreaking album, Days of Future Passed, which celebrates it’s 50th anniversary this year.c They looked and sounded great, and there was a lot of magic in the air as they recreated this landmark album live on stage. http://rocksubculture.com/2017/06/20/the-moody-blues-at-ironstone-amphitheatre-murphys-california-6182017-concert-review-photos/ 1/10 7/5/2017 The Moody Blues at Ironstone Amphitheatre | Murphys, California | 6/18/2017 (Concert Review + Photos) What: Days of Future Passed 50th Anniversary Tour Who: The Moody Blues Venue: Ironstone Amphitheatre at Ironstone Vineyards Where: Murphys, California Promoter: Richter Entertainment Group When: June 18, 2017 Seating: (house photographer) Richter Entertainment Group’s Summer Concert Season at Ironstone Amphitheatre in Murphys in 2017 features Toby Keith, Boston, Joan Jett & The Blackhearts, John Mellencamp, The Moody Blues, Jason Mraz, Lindsey Buckingham and Christine McVie, matchbox twenty, Counting Crows, Steve Miller Band, Peter Frampton, Willie Nelson, Kenny G, George Benson, and more!c It’s all taking place in June, July, August and September this year. -

Book Review with TTU Libraries Cover Page

BOOK REVIEW: BEYOND AND BEFORE: THE FORMATIVE YEARS OF YES BY PETER BANKS The Texas Tech community has made this publication openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters to us. Citation Weiner, R.G. (2008). [Review of the book Beyond and Before: The Formative Years of Yes by Peter Banks]. Popular Music and Society, 31(1), 136-139. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007769908591748 Citable Link http://hdl.handle.net/2346/1546 Terms of Use CC-BY Title page template design credit to Harvard DASH. 136 Book Reviews Hammond’s myopic vision, his unrelenting determination, and his deep personal sorrows, but to his friends and supporters Hammond was a trying project. Perhaps, as Prial suggests, Hammond’s relationship to the Vanderbilts did him more good in his early years in music than his social skills. There are questions unanswered and undeveloped in this biography related to Hammond the man, such as his falling out with Aretha Franklin or his quick parting with Dylan. Each chapter of this book comes (another assault on your pocketbook) with a wonderful ‘‘discography’’ that should slow down the pace of reading but will contribute to a great start in building a library of American music of the 20th century. It is quite something how much music Hammond had a role in, and this portion of the book is an important reminder of the times and genres Hammond touched. As with all biographies there are problems and limitations. For those of us raised in the second half of the century, The Producer fails to deliver the same magic surrounding the discovery and signing of ‘‘our’’ heroes as it does around the early stars. -

Moody Blues Release

Adrian Bohm Presents…… THE MOODY BLUES WORLD TOUR 2005 MELBOURNE PALAIS THEATRE SUNDAY APRIL 10 SYDNEY STATE THEATRE TUESDAY APRIL 12 WEDNESDAY APRIL 13 THURSDAY APRIL 14 BRISBANE CONVENTION CENTRE SATURDAY APRIL 16 With a career that spans almost 40 years The Moody Blues are one of the most enduring rock bands in music history. They have generated a legendary list of hit songs that are regarded as some of the most groundbreaking and innovative music of our time. Justin Hayward, John Lodge and Graeme Edge continue their magical music legacy with the first Australian tour in 18 years. A legendary band with an incredible list of hits including NIGHTS IN WHITE SATIN, RIDE MY SEE SAW, THE STORY IN YOUR EYES, ISN’T LIFE STRANGE, QUESTION, I’M JUST A SINGER IN A ROCK AND ROLL BAND, to name few. The Moody Blues have sold over 55 millions albums and received multi platinum and gold albums and have, over the course of several decades, performed sold out tours, making them one of the top grossing album and touring bands ever. The Moody Blues first album DAYS OF FUTURE PASSED was released in 1967 and was a ground breaking concept album that for the first time fused an orchestra with electric guitars. The album was so unique in its approach that it became a landmark moment in popular music history. Their record company, Decca Records had requested that the band record an album to test stereo recording, which was in its infancy at the time. Decca being a mainly classical label asked the Moody Blues to record a rock version of Dvorak’s 9th Symphony. -

The Musical Characteristics of the Beatles

The Musical Characteristics of the Beatles The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Education Bureau 2009 The Musical Characteristics of the Beatles Michael Saffle Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. All rights reserved. No part of this publication can be reproduced in any form or by any means, or otherwise, without the prior written consent of the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. Content 1 The Beatles: An Introduction 1 2 The Beatles as Composers/Performers: A Summary 7 3 Five Representative Songs and Song Pairs by the Beatles 8 3.1 “Love Me Do” and “Please Please Me” (1962) 8 3.2 “Michelle” and “Yesterday” (1965) 12 3.3 “Taxman” and “Eleanor Rigby” (1966) 14 3.4 “When I’m Sixty-Four” (1967) 16 3.5 “Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds” (1967) 18 4 The Beatles: Concluding Observations 21 5 Listening Materials 23 6 Musical Scores 23 7 Reading List 24 8 References for Further Study 25 9 Appendix 27 (Blank Page) 1 The Beatles: An Introduction The Beatles—sometimes referred to as the ‘Fab Four’—have been more influential than any other popular-music ensemble in history. Between 1962, when they made their first recordings, and 1970, when they disbanded, the Beatles drew upon several styles, including rock ‘n’ roll, to produce rock: today a term that almost defines today’s popular music. In 1963 their successes in England as live performers and recording artists inspired Beatlemania, which calls to mind the Lisztomania associated with the spectacular success of Franz Liszt’s 1842 German concert tour. -

Music & Entertainment

Hugo Marsh Neil Thomas Forrester Director Shuttleworth Director Director Music & Entertainment Tuesday 18th & Wednesday 19th May 2021 at 10:00 Viewing by strict appointment from 6th May For enquires relating to the Special Auction Services auction, please contact: Plenty Close Off Hambridge Road NEWBURY RG14 5RL Telephone: 01635 580595 Email: [email protected] www.specialauctionservices.com David Martin Dave Howe Music & Music & Entertainment Entertainment Due to the nature of the items in this auction, buyers must satisfy themselves concerning their authenticity prior to bidding and returns will not be accepted, subject to our Terms and Conditions. Additional images are available on request. Buyers Premium with SAS & SAS LIVE: 20% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 24% of the Hammer Price the-saleroom.com Premium: 25% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 30% of the Hammer Price 10. Iron Maiden Box Set, The First Start of Day One Ten Years Box Set - twenty 12” singles in ten Double Packs released 1990 on EMI (no cat number) - Box was only available The Iron Maiden sections in this auction by mail order with tokens collected from comprise the first part of Peter Boden’s buying the records - some wear to edges Iron Maiden collection (the second part and corners of the Box, Sleeves and vinyl will be auctioned in July) mainly Excellent to EX+ Peter was an Iron Maiden Superfan and £100-150 avid memorabilia collector and the items 4. Iron Maiden LP, The X Factor coming up in this and the July auction 11. Iron Maiden Picture Disc, were his pride and joy, carefully collected Double Album - UK Clear Vinyl release 1995 on EMI (EMD 1087) - Gatefold Sleeve Seventh Son of a Seventh Son - UK Picture over 30 years. -

ENT Hayward Prepdf

Twenty-First Century Troubadour: Justin Hayward on French Connections, Songwriting, and Literature Interview with Barbara Havercroft Born in 1946 in Swindon, England, Justin Hayward is the lead singer, song- writer, and guitarist with the legendary band The Moody Blues. His renowned, highly successful career in music is now in its sixth decade, and is characterized by excellence and innovation in popular music. The Moody Blues have sold more than seventy million albums and have been awarded more than a dozen platinum and gold discs. Justin Hayward has also released seven solo albums and has received numerous prestigious awards, such as the Ivor Novello Award for Outstanding Achievement in Music, awarded in May 20131. The following telephone interview was conducted at the University of Toronto on Monday, June 10, 2013. Barbara Havercroft §1 After you and John Lodge joined the Moody Blues in August, 1966, the band continued performing the rhythm and blues music played by the previous incarnation of the group. At this point, in the late sixties, you and your four band- mates decided to travel to Belgium to work. Why did you choose Belgium? Were there conditions in Belgium that were conducive to the band’s metamorphosis and the conception of new material, including the Days of Future Passed composi- tions2? Justin Hayward Actually, the band’s metamorphosis came a bit later. You must remember that nothing is planned in this band. We just stumble into things and lucky accidents and great big slices of luck happen to us. So there was no plan. We went to Belgium playing the old rhythm and blues set, which we continued playing for about three or four months after John and I joined [the group] and we simply weren’t very good at it. -

Walsh Proposes Coordinating Unit, Claims Support Campus Carnival

(ftmmcirttntt Haflg (Eamjjua Serving Storrs Since 1896 VOL. LXXX NO. 65 STORRS, CONNECTICUT TUESDAY, FEBRUARY I, 1977 Region Walsh proposes lucks out in crisis coordinating unit, United Press International New England's heavy reliance claims support upon oil for heating homes, businesses and factories is ironi- By JOHN HILL men! OK Walsh's proposal Mon- cally paying dividends this harsh Campus News Staff day, but said the four students on winter and residents of the region A bill to reorganize public a lb-member council members consider themselves lucky com- higher education in a manner sounded "impractical at first." pared to people in the Midwest, similar to a plan endorsed by the Jacobs said if student trustees Pennsylvania and New York. UConn Board of Trustees has served two-year terms as they do New England has had more than been submitted to the legisla- now on UConn's board. "It would its share of snow, cold and ice this ture's Education Committee, with lead to a lot of student trustee winter, but the problem with the bill's sponsor claiming turnover." heating oil, although its cost enough support to have the plan "Problems like this will have to continues to escalate, has not enacted as law. be resolved before I can comment reached the crisis stage as far as State Rep. Robert "Skip" on it." Jacobs said. supplies are concerned. Walsh. D-Coventry. the sponsor Education Committee co- However, preparations are und- of last year's ill-fated regents' chairman State Rep. Abraham er way on several fronts to cope plan, has submitted a bill that Glassman. -

The Moody Blues Tour / Set List Project - Updated April 9, 2006

The Moody Blues Tour / Set List Project - updated April 9, 2006 compiled by Linda Bangert Please send any additions or corrections to Linda Bangert ([email protected]) and notice of any broken links to Neil Ottenstein ([email protected]). This listing of tour dates, set lists, opening acts, additional musicians was derived from many sources, as noted on each file. Of particular help were "Higher and Higher" magazine and their website at www.moodies- magazine.com and the Moody Blues Official Fan Club (OFC) Newsletters. For a complete listing of people who contributed, click here. Particular thanks go to Neil Ottenstein, who hosts these pages, and to Bob Hardy, who helped me get these pages converted to html. One-off live performances, either of the band as a whole or of individual members, are not included in this listing, but generally can be found in the Moody Blues FAQ in Section 8.7 - What guest appearances have the band members made on albums, television, concerts, music videos or print media? under the sub-headings of "Visual Appearances" or "Charity Appearances". The current version of the FAQ can be found at www.toadmail.com/~notten/FAQ-TOC.htm I've construed "additional musicians" to be those who played on stage in addition to the members of the Moody Blues. Although Patrick Moraz was legally determined to be a contract player, and not a member of the Moody Blues, I have omitted him from the listing of additional musicians for brevity. Moraz toured with the Moody Blues from 1978 through 1990. From 1965-1966 The Moody Blues were Denny Laine, Clint Warwick, Mike Pinder, Ray Thomas and Graeme Edge, although Warwick left the band sometime in 1966 and was briefly replaced with Rod Clarke. -

The Ed Palermo Big Band Is Making America Un-Great Again with A

Bio information: THE ED PALERMO BIG BAND Title: THE GREAT UN-AMERICAN SONGBOOK VOLUMES 1 & 2 (Cuneiform Rune 435/436) Format: 2xCD / DIGITAL Cuneiform Promotion Dept: (301) 589-8894 / Fax (301) 589-1819 Press and world radio: [email protected] | North American and world radio: [email protected] www.cuneiformrecords.com FILE UNDER: JAZZ / BIG BAND JAZZ The Ed Palermo Big Band is Making America Un-Great Again with a Brilliant Blast of Anglophilia, transforming British Rock Treasures into Wildly Inventive Jazz Vehicles on the Double Album: The Great Un-American Songbook Volumes 1 & 2 From the Beatles, Rolling Stones and Jeff Beck to King Crimson, Traffic, and Jethro Tull, Palermo’s 18-piece ensemble Storms the British Invasion and Plants the American Flag (upside down) Crazy times call for outrageous music, and few jazz ensembles are better prepared to meet the surreality of this reality-TV-era than the antic and epically creative Ed Palermo Big Band. The New Jersey saxophonist, composer and arranger is best known for his celebrated performances interpreting the ingenious compositions of Frank Zappa, an extensive body of work documented on previous Cuneiform albums such as 2006’s Take Your Clothes Off When You Dance and 2009’s Eddy Loves Frank. His fifth project for the label, The Great Un-American Songbook Volumes 1 & 2 is a love letter to the rockers who ruled the AM and FM airwaves in the 1960s via successive waves of the British Invasion. Featuring largely the same stellar cast of players as last year’s gloriously eclectic One Child Left Behind, the 18-piece EPBB lovingly reinvents songs famous and obscure, leaving them readily recognizable and utterly transformed. -

A Brief History of Analog Synthesis Ondioline

Product Information Document Synthesizers and Samplers K-2 Analog and Semi-Modular Synthesizer with Dual VCOs, Ring Modulator, External Signal Processor, 16-Voice Poly Chain and Eurorack Format ## Amazing analog synthesizer with dual VCO design allows for insanely fat music creation ## Authentic reproduction of original circuitry with matched transistors A Brief History of and JFETs Analog Synthesis ## Pure analog signal path based on The modern synthesizer’s evolution authentic VCO, VCF and VCA designs began in 1919, when a Russian physicist ## Semi-modular architecture named Lev Termen (also known as with default routings requires no patching for immediate Léon Theremin) invented one of the performance first electronic musical instruments – ## First and second generation filter the Theremin. It was a simple oscillator design (high pass/low pass with peak/resonance) that was played by moving the performer’s hand in the vicinity of the ## 4 variable oscillator shapes with variable pulse widths and ring instrument’s antenna. An outstanding modulation for ultimate sounds example of the Theremin’s use can be ## Dedicated and fully analog heard on the Beach Boys iconic smash triangle/square wave LFO hit “Good Vibrations”. ## 2 analog Envelope Generators for modulation of VCF and VCA ## 16-voice Poly Chain allows Ondioline combining multiple synthesizers for In the late 1930s, French musician up to 16 voice polyphony Georges Jenny invented what he called ## Complete Eurorack solution – the Ondioline, a monophonic electronic main module can be transferred keyboard capable of generating a wide range to a standard Eurorack case of sounds. The keyboard even allowed the player to produce natural-sounding vibrato by ## 36 controls give you direct and real-time access to all important depressing a key and using side-to-side finger parameters movements. -

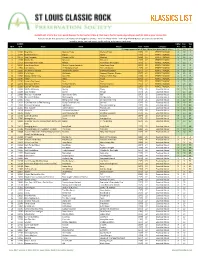

KLASSICS LIST Criteria

KLASSICS LIST criteria: 8 or more points (two per fan list, two for U-Man A-Z list, two to five for Top 95, depending on quartile); 1984 or prior release date Sources: ten fan lists (online and otherwise; see last page for details) + 2011-12 U-Man A-Z list + 2014 Top 95 KSHE Klassics (as voted on by listeners) sorted by points, Fan Lists count, Top 95 ranking, artist name, track name SLCRPS UMan Fan Top ID # ID # Track Artist Album Year Points Category A-Z Lists 95 35 songs appeared on all lists, these have green count info >> X 10 n 1 12404 Blue Mist Mama's Pride Mama's Pride 1975 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 1 2 12299 Dead And Gone Gypsy Gypsy 1970 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 2 3 11672 Two Hangmen Mason Proffit Wanted 1969 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 5 4 11578 Movin' On Missouri Missouri 1977 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 6 5 11717 Remember the Future Nektar Remember the Future 1973 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 7 6 10024 Lake Shore Drive Aliotta Haynes Jeremiah Lake Shore Drive 1971 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 9 7 11654 Last Illusion J.F. Murphy & Salt The Last Illusion 1973 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 12 8 13195 The Martian Boogie Brownsville Station Brownsville Station 1977 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 13 9 13202 Fly At Night Chilliwack Dreams, Dreams, Dreams 1977 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 14 10 11696 Mama Let Him Play Doucette Mama Let Him Play 1978 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 15 11 11547 Tower Angel Angel 1975 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 19 12 11730 From A Dry Camel Dust Dust 1971 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 20 13 12131 Rosewood Bitters Michael Stanley Michael Stanley 1972 27 PERFECT