Branches Vol 13

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Strangers No More: “When Harry Met [Dante]…”](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1371/strangers-no-more-when-harry-met-dante-31371.webp)

Strangers No More: “When Harry Met [Dante]…”

Kate Dowling Bryn Mawr School, Baltimore, MD Dante Senior Elective at Gilman School Strangers No More: “When Harry Met [Dante]…” If Dante were to listen to “Stranger with the Melody” at this point on his journey, I think he would be able to relate it a lot to his sense of moving into a different part of his life. Right now, Dante is overcome with emotion, as he has lost Vergil but also been reunited with Beatrice and made it to Paradise. The stranger in the poem reminds me a lot of Vergil, since at the beginning of the song his presence seems almost godlike. When the anonymous voice comes through the walls to Harry, it seems like it is not even attached to a real person; instead, this man appeared just for Harry, as if he was meant to hear his song. Just like this stranger, Vergil appears to Dante and seems almighty. Through Inferno he knows everything and can tell Dante exactly what to do. On Mount Purgatory, Vergil is more unsure, but he still manages to get Dante to the top successfully. Vergil cannot stay with Dante forever, though, and soon we see how Vergil is limited by his Paganism and restricted to his place in Limbo. Just like Vergil, this unknown singer is limited, in this case by his own emotions. The singer can only repeat the same words over and over again, and he seems lost because he can never move on from them. He never will be able to either, because he says that only his girl can tell him the words, while he can just play the music. -

Radio Essentials 2012

Artist Song Series Issue Track 44 When Your Heart Stops BeatingHitz Radio Issue 81 14 112 Dance With Me Hitz Radio Issue 19 12 112 Peaches & Cream Hitz Radio Issue 13 11 311 Don't Tread On Me Hitz Radio Issue 64 8 311 Love Song Hitz Radio Issue 48 5 - Happy Birthday To You Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 21 - Wedding Processional Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 22 - Wedding Recessional Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 23 10 Years Beautiful Hitz Radio Issue 99 6 10 Years Burnout Modern Rock RadioJul-18 10 10 Years Wasteland Hitz Radio Issue 68 4 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night Radio Essential IssueSeries 44 Disc 44 4 1975, The Chocolate Modern Rock RadioDec-13 12 1975, The Girls Mainstream RadioNov-14 8 1975, The Give Yourself A Try Modern Rock RadioSep-18 20 1975, The Love It If We Made It Modern Rock RadioJan-19 16 1975, The Love Me Modern Rock RadioJan-16 10 1975, The Sex Modern Rock RadioMar-14 18 1975, The Somebody Else Modern Rock RadioOct-16 21 1975, The The City Modern Rock RadioFeb-14 12 1975, The The Sound Modern Rock RadioJun-16 10 2 Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love Radio Essential IssueSeries 22 Disc 22 4 2 Pistols She Got It Hitz Radio Issue 96 16 2 Unlimited Get Ready For This Radio Essential IssueSeries 23 Disc 23 3 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone Radio Essential IssueSeries 22 Disc 22 16 21 Savage Feat. J. Cole a lot Mainstream RadioMay-19 11 3 Deep Can't Get Over You Hitz Radio Issue 16 6 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun Hitz Radio Issue 46 6 3 Doors Down Be Like That Hitz Radio Issue 16 2 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes Hitz Radio Issue 62 16 3 Doors Down Duck And Run Hitz Radio Issue 12 15 3 Doors Down Here Without You Hitz Radio Issue 41 14 3 Doors Down In The Dark Modern Rock RadioMar-16 10 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time Hitz Radio Issue 95 3 3 Doors Down Kryptonite Hitz Radio Issue 3 9 3 Doors Down Let Me Go Hitz Radio Issue 57 15 3 Doors Down One Light Modern Rock RadioJan-13 6 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone Hitz Radio Issue 31 2 3 Doors Down Feat. -

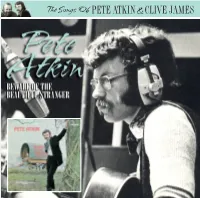

The Songs of PETE ATKIN&CLIVE JAMES

EDSS 1029 PA BOTBS booklet 6/1/09 17:38 Page 2 EDSS 1029 The Songs Of PETE ATKIN&CLIVE JAMES 28 1 EDSS 1029 PA BOTBS booklet 6/1/09 17:38 Page 4 Beware Of The Beautiful Arranged by Pete Atkin Project co-ordination – Val Jennings Strings arranged by Nick Harrison CD package – Jools at Mac Concept Stranger Produced by Don Paul CD mastering – Alchemy Engineered by Tom Allom Ephemera courtesy of the collections of Fontana 6309 011, 1970. Re-issued on RCA Recorded at Regent Sound A, Tottenham Pete Atkin and Clive James SF 8387 in 1973 in a re-designed sleeve with CD front cover main photo and strapline photo – “Touch Has A Memory” replaced by “Be Street, London W1, on 31st March and 1st & 2nd April 1970 Sophie Baker Careful When They Offer You The Moon”, and Huge thanks – Pete Atkin, Clive James, Simon Mixed between 2 pm and 6 pm with “Sunrise” as the second song. Platz, Steve Birkill, Ronen Guha on 2nd April 1970 and Caroline Cook “Be Careful When They Offer You The Moon” and “A Man Who’s Been Around” For everything (and we mean everything) relating to were recorded at Tin Pan Alley Studio, Pete Atkin’s works, visit www.peteatkin.com, but Denmark Street on 11th August 1970 make sure you’ve got plenty of time to spend! Then of course, you’ll want to visit Credits – British Rail, Arthur Guinness, www.clivejames.com William Hazlitt, John Keats, Meade Lux Lewis, Garcia Lorca, Odham’s Junior Pete Atkin’s albums on the Encyclopaedia, Auguste Renoir, William Edsel label: Shakespeare and Duke Ellington (there never was another). -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

Madonna: Like a Crone

ROCK ON: WOMEN, AGEING AND POPULAR MUSIC MADONNA: LIKE A CRONE Reaching fifty in 2008 was a watershed year not just for Madonna, but also for her millions of fans. She is a vital figure for women across generations: through her performances she has popularised feminist politics and debate, and promoted a message of sexual empowerment. Much of her career has hinged on this concept of self-liberation and sexual expressiveness. As a young star she was powerfully seductive - one of the first female performers in the pop mainstream to capitalise on video as a marketing tool, and to make that nexus between sex, pop and commerce so explicit. She also challenged notions of the male/female gaze with her book Sex, and videos like 'Justify My Love'. Much of her allure was centred around her visual image, and her ability to combine an inclusive sexuality with compelling costume changes and personae. Female stars in her wake, from Britney Spears to Lady Gaga, have been clearly influenced by her ideas on performance and sexuality However, becoming a mature woman and a mother has presented her with a dilemma. She is fiercely competitive and it is a matter of personal pride to 'stay on top' in the singles market. But in having to compete with younger women, she is subject to the same pressures to look young, slim and beautiful. As a result, she has to continually sculpt and resculpt her body through rigorous workouts and diet regimes. The sculpted body first emerged when she shed the voluptuous 'Toy Boy' look of her early career for her 'Open Your Heart' video. -

Madonna's Postmodern Revolution

Journal of Literature and Art Studies, January 2021, Vol. 11, No. 1, 26-32 doi: 10.17265/2159-5836/2021.01.004 D DAVID PUBLISHING The Rebel Madame: Madonna’s Postmodern Revolution Diego Santos Vieira de Jesus ESPM-Rio, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil The aim is to examine Madonna’s revolution regarding gender, sexuality, politics, and religion with the focus on her songs, videos, and live performances. The main argument indicates that Madonna has used postmodern strategies of representation to challenge the foundational truths of sex and gender, promote gender deconstruction and sexual multiplicity, create political sites of resistance, question the Catholic dissociation between the physical and the divine, and bring visual and musical influences from multiple cultures and marginalized identities. Keywords: Madonna, postmodernism, pop culture, sex, gender, sexuality, politics, religion, spirituality Introduction Madonna is not only the world’s highest earning female entertainer, but a pop culture icon. Her career is based on an overall direction that incorporates vision, customer and industry insight, leveraging competences and weaknesses, consistent implementation, and a drive towards continuous renewal. She constructed herself often rewriting her past, organized her own cult borrowing from multiple subaltern subcultures, and targeted different audiences. As a postmodern icon, Madonna also reflects social contradictions and attitudes toward sexuality and religion and addresses the complexities of race and gender. Her use of multiple media—music, concert tours, films, and videos—shows how images and symbols associated with multiracial, LGBT, and feminist groups were inserted into the mainstream. She gave voice to political interventions in mass popular culture, although many critics argue that subaltern voices were co-opted to provide maximum profit. -

THE LIVING YEARS 1 Timbaland

Artist - Track Count mike & the mechanics - THE LIVING YEARS 1 timbaland - nelly furtado - justin - GIVE IT TO ME 1 wet wet wet - LOVE IS ALL AROUND 1 justin timberlake - MY LOVE 1 john mayer - WAITING ON THE WORLD TO CHANGE 1 duran duran - I DON'T WANT YOUR LOVE 1 tom walker - LEAVE A LIGHT ON 1 a fine frenzy - ALMOST LOVER 1 mariah carey - VISION OF LOVE 1 aura dione - SOMETHING FROM NOTHING 1 linkin park - NEW DIVIDE (from Transformers 2) 1 phil collins - GOING BACK 1 keane - SILENCED BY NIGHT 1 sigala - EASY LOVE 1 murray head - ONE NIGHT IN BANGKOK 1 celine dion - ONE HEART 1 reporter milan - STAJERSKA 1 michael jackson - siedah garrett - I JUST CAN'T STOP LOVING YOU 1 martin garrix feat usher - DON'T LOOK DOWN 1 k'naan - WAVIN' FLAG (OFFICIAL 2010 WORLD CUP SONG) 1 jennifer lopez & pitbull - DANCE AGAIN 1 maroon 5 - THIS SUMMER'S GONNA HURT 1 happy mondays - STEP ON 1 abc - THE NIGHT YOU MURDERED LOVE 1 heart - ALL I WANNA DO IS MAKING LOVE 1 huey lewis & the news - STUCK WITH YOU 1 ultravox - VIENNA 1 queen - HAMMER TO FALL 1 stock aitken waterman - ROADBLOCK 1 yazoo - ONLY YOU 1 billy idol - REBEL YELL 1 ashford & simpson - SOLID 1 loverboy - HEAVEN IN YOUR EYES 1 kaoma - LAMBADA 1 david guetta/sia - LET'S LOVE 1 rita ora/gunna - BIG 1 you me at six - ADRENALINE 1 shakira - UNDERNEATH YOUR CLOTHES 1 gwen stefani - LET ME REINTRODUCE MYSELF 1 cado - VSE, KAR JE TAM 1 atomic kitten - WHOLE AGAIN 1 dionne bromfield feat lil twist - FOOLIN 1 macy gray - STILL 1 sixpence none the richer - THERE SHE GOES 1 maraaya - DREVO 1 will young - FRIDAY'S CHILD 1 christina aguilera - WHAT A GIRL WANTS 1 jan plestenjak - lara - SOBA 102 1 barry white - YOU'RE THE FIRST THE LAST MY EVERYTHING 1 parni valjak - PROKLETA NEDELJA 1 pitbull - GIVE ME EVERYTHING TONIGHT 1 the champs - TEQUILA 1 colonia - ZA TVOJE SNENE OCI 1 nick kamen - I PROMISED MYSELF 1 gina g. -

The Foreigner

THE FOREIGNER By Larry Shue The Characters S/Sgt. "FROGGY" LeSUEUR CHARLIE BAKER BETTY MEEKS REV. DAVID MARSHALL LEE CATHERINE SIMMS OWEN MUSSER ELLARD SIMMS The Place: Betty Meeks' Fishing Lodge Resort, Tilghman County, Georgia, U.S.A. The Time: The Recent Past ACT I Scene 1: Evening. Scene 2: The following morning. ACT II Scene 1: Afernoon, two days later. Scene 2: That evening. 2 ACT I SCENE 1 In the darkness, rain and thunder. As the lights come up, we find ourselves in what was once the living-room of a log farmhouse, now adapted for service as a parlor for paying guests —middle-income summer people, mostly, who come to fish, and swim, and play a little cards at night, and to fill up on Betty Meeks' away-from-home cooking. We might think it still a living-room were it not for the presence of a small counter with modest candy and tobacco displays, a guest register, and a bell. Also, there is about one sofa too many, a small stove and its woodbin, and a coffee-table, on which a bowl of apples rests. Though we wouldn't know it from the first two dialects we hear, the fact is that we are in Tilghman County, Georgia, U.S.A. — two hours by good road south out of Atlanta, then pull off at Cooley's Food and Bait and call for directions. It used to be that Omer Meeks, who owned the lake house, would then have driven down and led you up the hill in his Dodge pickup. -

SONV3IH3PW a Sasaioni Soanisa Va Sazuvm Só a Svavzuvw SVQIA

noz ap sopnjsg SONV3IH3PW a sasaiONi soanisa III va sazuvM só a svavzuvw SVQIA ^0 A 7 p,. sopnjsg 3P 'The most gripping book Fve read in ages . Fascinating, HUGO HAMILTON disturbing and often very funny.' RODDY DOYLE In one of the finest memoirs to have emerged frorn Ireland THE in many years, the.acclaimed novelist Hugo Hamilton brings alive his German—Irish childhood in 1950s Dublin. Between his father's strict Irish nationalism and the softly SPECKLED spoken stories of his mother's German past, this little boy tells the tale of a whole family's homesickness for a country, and a language, they can call their own. PEOPLE 'An extraordinary achievement ... A wonderful, subtle, 'A wonderful book . thoughtful and compelling, problematic and humane book. It is about Ireland as well as smart and original, beautifully written.' about a particular family, but it is also about alternatives and complexities anywhere.' NICK HORNBY, SVNDAY 'TIMES GEORGE SZIRTES, 1R1SH TIMES 'This story about a battle over language and defeat 'in the language wars' is also a victory for eloquent writmg, crafty and cunning in its apparent sirnplicity.' HERMIONE LEE, GUARDIAN 'Hamilton's first masterpiece. To read The Speckled People is to remember why great wríting matters. A book for our times, and probably of ali time.' JOSEPH O'CONNOR, DAÍLY MA1L ISBN 978-0-00-714311-f) FSC li 9 41 LOVE THIS BOOK? WWW.SOOKARMY.COM mother told us not to be só interested in blood and took it away on the shovel. It's só cold, we stay in one room by the fire where it's nice and warm, but if you go from that room up to the Seven bedroom, it's like going out on the street and you need your coat on. -

Pdf, 312.59 KB

00:00:00 Music Transition “Crown Ones” off the album Stepfather by People Under The Stairs. 00:00:05 Oliver Wang Host Hello, I’m Oliver Wang. 00:00:07 Morgan Host And I’m Morgan Rhodes. You’re listening to Heat Rocks. Rhodes 00:00:09 Oliver Host Every episode we invite a guest to join us to talk about a heat rock, hot lava. And today we are going to be joining hands to take it back to 1994 and Two—or maybe it’s just II, I don’t know—the second album by the R&B mega smash group, Boyz II Men. 00:00:30 Music Music “Thank You” off the album II by Boyz II Men. Smooth, funky R&B. (I like this, I like this, I like...) I was young And didn't have nowhere to run I needed to wake up and see (and see) What's in front of me (na-na-na) There has to be a better way Sing it again a better way To show... 00:00:50 Morgan Host Boyz II Men going off, not too hard, not too soft— [Oliver says “ooo” appreciatively.] —could easily be considered a bit of a mantra for Shawn, Wanya, Nathan, and Michael, two tenors, a baritone, and a bass singer from Philly, after their debut album. The one that introduced us to their steez, and their melodies. This one went hella platinum. The follow-up, II. This album had hits that can be divided into three sections. Section one, couple’s therapy. -

Madonna - 1982 - 2009 : the Lyrics Book - 1 SOMMAIRE

Madonna - 1982 - 2009 : The Lyrics Book - www.madonnalex.net 1 SOMMAIRE P.03 P.21 P.51 P.06 P.26 P.56 P.09 P.28 P.59 P.10 P.35 P.66 P.14 P.40 P.74 P.15 P.42 P.17 P.47 Madonna - 1982 - 2009 : The Lyrics Book - www.madonnalex.net 2 ‘Cause you got the best of me Chorus: Borderline feels like I’m going to lose my mind You just keep on pushing my love over the borderline (repeat chorus again) Keep on pushing me baby Don’t you know you drive me crazy You just keep on pushing my love over the borderline Something in your eyes is makin’ such a fool of me When you hold me in your arms you love me till I just can’t see But then you let me down, when I look around, baby you just can’t be found Stop driving me away, I just wanna stay, There’s something I just got to say Just try to understand, I’ve given all I can, ‘Cause you got the best of me (chorus) Keep on pushing me baby MADONNA / Don’t you know you drive me crazy You just keep on pushing my love over the borderline THE FIRST ALBUM Look what your love has done to me 1982 Come on baby set me free You just keep on pushing my love over the borderline You cause me so much pain, I think I’m going insane What does it take to make you see? LUCKY STAR You just keep on pushing my love over the borderline written by Madonna 5:38 You must be my Lucky Star ‘Cause you shine on me wherever you are I just think of you and I start to glow BURNING UP And I need your light written by Madonna 3:45 Don’t put me off ‘cause I’m on fire And baby you know And I can’t quench my desire Don’t you know that I’m burning -

THE COLLECTED POEMS of HENRIK IBSEN Translated by John Northam

1 THE COLLECTED POEMS OF HENRIK IBSEN Translated by John Northam 2 PREFACE With the exception of a relatively small number of pieces, Ibsen’s copious output as a poet has been little regarded, even in Norway. The English-reading public has been denied access to the whole corpus. That is regrettable, because in it can be traced interesting developments, in style, material and ideas related to the later prose works, and there are several poems, witty, moving, thought provoking, that are attractive in their own right. The earliest poems, written in Grimstad, where Ibsen worked as an assistant to the local apothecary, are what one would expect of a novice. Resignation, Doubt and Hope, Moonlight Voyage on the Sea are, as their titles suggest, exercises in the conventional, introverted melancholy of the unrecognised young poet. Moonlight Mood, To the Star express a yearning for the typically ethereal, unattainable beloved. In The Giant Oak and To Hungary Ibsen exhorts Norway and Hungary to resist the actual and immediate threat of Prussian aggression, but does so in the entirely conventional imagery of the heroic Viking past. From early on, however, signs begin to appear of a more personal and immediate engagement with real life. There is, for instance, a telling juxtaposition of two poems, each of them inspired by a female visitation. It is Over is undeviatingly an exercise in romantic glamour: the poet, wandering by moonlight mid the ruins of a great palace, is visited by the wraith of the noble lady once its occupant; whereupon the ruins are restored to their old splendour.