Semitic Gutturals and Distinctive Feature Theory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feature Geometry in Disordered Phonologies

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by IUScholarWorks CLINICAL LINGUISTICS & PHONETICS, 1991, VOL. 5, NO. 4, 329-337 Feature geometry in disordered phonologies STEVEN B. CHIN and DANIEL A. DINNSEN Department of Linguistics, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN 47405, USA (Received 29 January 1991; accepted 8 May 1991) Abstract Two types of systems are in general use for the description and classification of consonants in disordered phonological systems: conventional place-voice-man- ner and standard distinctive features. This paper proposes the use of a third model, feature geometry, which is an analysis framework recently developed in the linguistic study of primary languages. Feature geometry allows for relatively independent behaviour of individual distinctive features, but also organizes them into hierarchies in order to capture the fact that features very often act together in rules. Application of the feature geometry to the study of the phonologies of 40 misarticulating children, specifically to the phenomena of apparent cluster coalescence, fricative/affricate alternations, and alveolar stop/glottal stop alter- nations, reveals that feature geometry provides better explanations for represen- tations and rules in disordered systems than either of the other two frameworks. Keywords: Feature geometry, distinctive features, functional misarticulation, phonological disorders. For personal use only. Introduction Two types of systems are in general use for the description and classification of consonants in disordered phonological systems. These are first, systems using place of articulation, voicing, and manner of articulation; and second, systems using distinctive features. The choice of using one or the other type of description is often more a matter of training tradition rather than true theoretical inclination. -

Module 30: Distinctive Features-II

Module 30: Distinctive Features-II . Objectives: • To carry over from the previous module and make the student familiar with some novel concepts relating to distinctive features, such as ambiguity and underspecification • To show the student the rationale of the proposals for distinctive features through exercises Topics: 30.1 Introduction 30.2 Dorsal features 30.3 Contour features 30.4 Prosodic features 30.5 Ambiguous features 30.6 Contrastive and redundant features: Underspecification 30.7 Summary 30.1 Introduction You were introduced to the notion of distinctive features in phonology in the preceding module. The need for the notion and the development of the theory of distinctive features arose, as we saw, on account of the problem of characterizing natural classes of sounds in structural phonology. As phonological processes involve natural classes of sounds, phonological analysis without the characterization of natural classes is unable to explain the naturalness of phonological processes as well as the distinction between a possible and impossible process. In the present module you will be further introduced to a discussion of some of the inadequacies of the best known account of distinctive features. Towards the end of the module, some aspects of uncertain interpretations of a few distinctive features will be taken up for caution. Finally the notion of Underspecification of features will be taken up for brief elaboration, as it relates to the theory in its earlier as well as later versions. 1 The main goal in presenting these topics is to have them put in one place because of their relevance to the topics that will be taken up for critical discussion in the course on Advanced Phonology. -

LINGUISTICS 221 Lecture #3 DISTINCTIVE FEATURES Part 1. an Utterance Is Composed of a Sequence of Discrete Segments. Is the Segm

LINGUISTICS 221 Lecture #3 DISTINCTIVE FEATURES Part 1. An utterance is composed of a sequence of discrete segments. Is the segment indivisible? Is the segment the smallest unit of phonological analysis? If it is, segments ought to differ randomly from one another. Yet this is not true: pt k prs What is the relationship between members of the two groups? p t k - the members of this set have an internal relationship: they are all voiceles stops. p r s - no such relationship exists p b d s bilabial bilabial alveolar alveolar stop stop stop fricative voiceless voiced voiced voiceless SIMILARITIES AND DIFFERENCES! Segments may be viewed as composed of sets of properties rather than indivisible entities. We can show the relationship by listing the properties of each segment. DISTINCTIVE FEATURES • enable us to describe the segments in the world’s languages: all segments in any language can be characterized in some unique combination of features • identifies groups of segments → natural segment classes: they play a role in phonological processes and constraints • distinctive features must be referred to in terms of phonetic -- articulatory or acoustic -- characteristics. 1 Requirements on distinctive feature systems (p. 66): • they must be capable of characterizing natural segment classes • they must be capable of describing all segmental contrasts in all languages • they should be definable in phonetic terms The features fulfill three functions: a. They are capable of describing the segment: a phonetic function b. They serve to differentiate lexical items: a phonological function c. They define natural segment classes: i.e. those segments which as a group undergo similar phonological processes. -

Part 1: Introduction to The

PREVIEW OF THE IPA HANDBOOK Handbook of the International Phonetic Association: A guide to the use of the International Phonetic Alphabet PARTI Introduction to the IPA 1. What is the International Phonetic Alphabet? The aim of the International Phonetic Association is to promote the scientific study of phonetics and the various practical applications of that science. For both these it is necessary to have a consistent way of representing the sounds of language in written form. From its foundation in 1886 the Association has been concerned to develop a system of notation which would be convenient to use, but comprehensive enough to cope with the wide variety of sounds found in the languages of the world; and to encourage the use of thjs notation as widely as possible among those concerned with language. The system is generally known as the International Phonetic Alphabet. Both the Association and its Alphabet are widely referred to by the abbreviation IPA, but here 'IPA' will be used only for the Alphabet. The IPA is based on the Roman alphabet, which has the advantage of being widely familiar, but also includes letters and additional symbols from a variety of other sources. These additions are necessary because the variety of sounds in languages is much greater than the number of letters in the Roman alphabet. The use of sequences of phonetic symbols to represent speech is known as transcription. The IPA can be used for many different purposes. For instance, it can be used as a way to show pronunciation in a dictionary, to record a language in linguistic fieldwork, to form the basis of a writing system for a language, or to annotate acoustic and other displays in the analysis of speech. -

Dominance in Coronal Nasal Place Assimilation: the Case of Classical Arabic

http://elr.sciedupress.com English Linguistics Research Vol. 9, No. 3; 2020 Dominance in Coronal Nasal Place Assimilation: The Case of Classical Arabic Zainab Sa’aida Correspondence: Zainab Sa’aida, Department of English, Tafila Technical University, Tafila 66110, Jordan. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6645-6957, E-mail: [email protected] Received: August 16, 2020 Accepted: Sep. 15, 2020 Online Published: Sep. 21, 2020 doi:10.5430/elr.v9n3p25 URL: https://doi.org/10.5430/elr.v9n3p25 Abstract The aim of this study is to investigate place assimilation processes of coronal nasal in classical Arabic. I hypothesise that coronal nasal behaves differently in different assimilatory situations in classical Arabic. Data of the study were collected from the Holy Quran. It was referred to Quran.com for the pronunciations and translations of the data. Data of the study were analysed from the perspective of Mohanan’s dominance in assimilation model. Findings of the study have revealed that coronal nasal shows different assimilatory behaviours when it occurs in different syllable positions. Coronal nasal onset seems to fail to assimilate a whole or a portion of the matrix of a preceding obstruent or sonorant coda within a phonological word. However, coronal nasal in the coda position shows different phonological behaviours. Keywords: assimilation, dominance, coronal nasal, onset, coda, classical Arabic 1. Introduction An assimilatory situation in natural languages has two elements in which one element dominates the other. Nasal place assimilation occurs when a nasal phoneme takes on place features of an adjacent consonant. This study aims at investigating place assimilation processes of coronal nasal in classical Arabic (CA, henceforth). -

''Phonetic Bases of Distinctive Features'': Introduction

”Phonetic bases of distinctive features”: Introduction George N. Clements, Pierre Hallé To cite this version: George N. Clements, Pierre Hallé. ”Phonetic bases of distinctive features”: Introduction. Journal of Phonetics, Elsevier, 2010, 1 (38), pp.3-9. 10.1016/j.wocn.2010.01.004. halshs-00684211 HAL Id: halshs-00684211 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00684211 Submitted on 4 Apr 2012 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Journal of Phonetics special issue "Phonetic Bases of Distinctive Features" Introduction G. N. Clements and P. A. Hallé Laboratoire de Phonétique et Phonologie (LPP) CNRS/Paris 3 Sorbonne-nouvelle, Paris, France 2 1. Presentation Distinctive features have long been involved in the study of spoken language, and in one form or another remain central to the study of phonological patterning within and across languages. However, their phonetic nature as well as their role in mental representation, speech production, and speech processing has been a matter of less agreement. Many phoneticians consider features to be too abstract for the purposes of phonetic study, and have tended to explore alternative models for representing speech (e.g., gestures, prototypes, exemplars). -

An Ultrasound Investigation of Secondary Velarization in Russian

An Ultrasound Investigation of Secondary Velarization in Russian by Natallia Litvin B.A., Minsk State Linguistic University, 2009 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Linguistics Natallia Litvin, 2014 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee An Ultrasound Investigation of Secondary Velarization in Russian by Natallia Litvin BA, Minsk State Linguistic University, 2009 Supervisory Committee Dr. Sonya Bird (Department of Linguistics) Supervisor Dr. John H. Esling (Department of Linguistics) Departmental Member iii Abstract Supervisory Committee Dr. Sonya Bird (Department of Linguistics) Supervisor Dr. John H. Esling (Department of Linguistics) Departmental Member The present study aims to resolve previous disputes about whether or not non-palatalized consonants exhibit secondary velarization in Russian, and if so what this corresponds to articulatorily. Three questions are asked: 1) are Russian non-palatalized consonants velarized or not? If so, 2) what are the articulatory properties of velarization? and 3) how is the presence or absence of secondary velarization affected by adjacent vowels? To answer these questions, laryngeal and lingual ultrasound investigations were conducted on a range of non-palatalized consonants across different vowel contexts. The results of the study show that 1) Russian non- palatalized consonants are not pharyngealized in the sense of Esling (1996, 1999, 2005), 2) /l/ and /f/ are uvularized, 3) /s/ and /ʂ/ can feature either uvularization or velarization. The study also shows that secondary articulations of Russian non-palatalized consonants are inherent rather than dependent on vowel context. -

Human Beatboxing : a Preliminary Study on Temporal Reduction

Human Beatboxing : A preliminary study on temporal reduction. Alexis Dehais Underdown1, Paul Vignes1, Lise Crevier Buchman1,2 & Didier Demolin1 1 Laboratoire de Phonétique et Phonologie (Sorbonne Nouvelle / CNRS), 2 Hopital Foch, Univ. VSQ. [email protected] 1. Introduction Speech rate is known to be a factor of reduction affecting supralaryngeal gestures [4] [6] [1] and laryngeal gestures [5] depending on the prosodic structure [3]. An acoustic study [2] showed that beatboxing rate has articulatory effects on hi-hats in medial and final positions but that the overall production was not found to be affected. In the present study we are presenting an experiment based on a beatboxing speeding up paradigm. We used a single metric and rhythmical pattern to create various beatboxed patterns (BP). Human Beatboxing (HBB) seems to rely on different articulatory skills than speech because it does not obey to linguistic constraints. How do beatboxing rate affect sound duration ? We expect that (1) the faster the production, the shorter sound duration (2) affricates, trills and fricatives will shorten more than stops (3) position in the pattern influences sound reduction. 2. Methods A 32 y.o. professional beatboxer took part in the experiment. The recorded material was controlled in terms of sound pattern and rhythm. Indeed, to facilitate the comparison of beatboxing recordings we used only one metric pattern that we transposed into 12 Beatbox patterns (BP). Table 1 shows an example of two of the 12 BP created for the study. There is only one voiced sound (i.e. [ɓ]) in the corpus. Table 1 : Example of the structure of a Beatboxed Pattern Metric Rhythm Low High Long High Low Low High Long High Positions 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 BP1 [p’] [͡ts’] [↓k͡ L̥ ] [͡ts’] [p’] [p’] [͡ts’] [↓k͡ L̥ ] [͡ts’] BP2 [↓ʙ̥ ˡ] [͡ts’] [ʡhə̥ ] [͡ts’] [↓p] [↓ʙ̥ ˡ] [͡ts’] [ʡhə̥ ] [͡ts’] Concerning the rhythm, it was controlled using a vibrating metronome placed on his wrist. -

17. Distinctive Features : the Blackwell Companion to Phonology

Bibliographic Details The Blackwell Companion to Phonology Edited by: Marc van Oostendorp, Colin J. Ewen, Elizabeth Hume and Keren Rice eISBN:17. Distinctive 9781405184236 Features JeffPrintJeff MielkeMielkepublication date: 2011 Sections 1 Introduction 2 Building a model of phonological behavior 3 Proposed features 4 One model or many? 5 New types of experimental evidence Notes REFERENCES 1 Introduction Distinctive feature theory is an effort to identify the phonetic dimensions that are important for lexical contrasts and phonological patterns in human languages. The set of features and its explanatory role have both expanded over the years, with features being used to define not only the contrasts but the groupings of sounds involved in rules and phonotactic restrictions, as well as the changes involved in rules. Distinctive features have been used to account for a wide range of phonological phenomena, and this chapter overviews the incremental steps by which the feature model has changed, along with some of the evidence for these steps. An important point is that many of the steps involve non-obvious connections, something that is harder to see in hindsight. Recognizing that these steps are not obvious is important in order to see the insights that have been made in the history of distinctive feature theory, and to see that these claims are associated with differing degrees of evidence, despite often being assumed to be correct. The structure of the chapter is as follows. §2 describes the series of non-obvious claims that led to modern distinctive feature theory, and §3 briefly describes the particular features that have been proposed. -

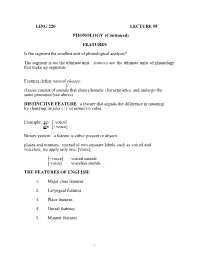

LING 220 LECTURE #8 PHONOLOGY (Continued) FEATURES Is The

LING 220 LECTURE #8 PHONOLOGY (Continued) FEATURES Is the segment the smallest unit of phonological analysis? The segment is not the ultimate unit: features are the ultimate units of phonology that make up segments. Features define natural classes: ↓ classes consist of sounds that share phonetic characteristics, and undergo the same processes (see above). DISTINCTIVE FEATURE: a feature that signals the difference in meaning by changing its plus (+) or minus (-) value. Example: tip [-voice] dip [+voice] Binary system: a feature is either present or absent. pluses and minuses: instead of two separate labels, such as voiced and voiceless, we apply only one: [voice] [+voice] voiced sounds [-voice] voiceless sounds THE FEATURES OF ENGLISH: 1. Major class features 2. Laryngeal features 3. Place features 4. Dorsal features 5. Manner features 1 1. MAJOR CLASS FEATURES: they distinguish between consonants, glides, and vowels. obstruents, nasals and liquids (Obstruents: oral stops, fricatives and affricates) [consonantal]: sounds produced with a major obstruction in the oral tract obstruents, liquids and nasals are [+consonantal] [syllabic]:a feature that characterizes vowels and syllabic liquids and nasals [sonorant]: a feature that refers to the resonant quality of the sound. vowels, glides, liquids and nasals are [+sonorant] STUDY Table 3.30 on p. 89. 2. LARYNGEAL FEATURES: they represent the states of the glottis. [voice] voiced sounds: [+voice] voiceless sounds: [-voice] [spread glottis] ([SG]): this feature distinguishes between aspirated and unaspirated consonants. aspirated consonants: [+SG] unaspirated consonants: [-SG] [constricted glottis] ([CG]): sounds made with the glottis closed. glottal stop [÷]: [+CG] 2 3. PLACE FEATURES: they refer to the place of articulation. -

An Autosegmental Account of Melodic Processes in Jordanian Rural Arabic

International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature E-ISSN: 2200-3592 & P-ISSN: 2200-3452 www.ijalel.aiac.org.au An Autosegmental Account of Melodic Processes in Jordanian Rural Arabic Zainab Sa’aida* Department of English, Tafila Technical University, P.O. Box 179, Tafila 66110, Jordan Corresponding Author: Zainab Sa’aida, E-mail: [email protected] ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history This study aims at providing an autosegmental account of feature spread in assimilatory situations Received: October 02, 2020 in Jordanian rural Arabic. I hypothesise that in any assimilatory situation in Jordanian rural Arabic Accepted: December 23, 2020 the undergoer assimilates a whole or a portion of the matrix of the trigger. I also hypothesise Published: January 31, 2021 that assimilation in Jordanian rural Arabic is motivated by violation of the obligatory contour Volume: 10 Issue: 1 principle on a specific tier or by spread of a feature from a trigger to a compatible undergoer. Advance access: January 2021 Data of the study were analysed in the framework of autosegmental phonology with focus on the notion of dominance in assimilation. Findings of the study have revealed that an undergoer assimilates a whole of the matrix of a trigger in the assimilation of /t/ of the detransitivizing Conflicts of interest: None prefix /Ɂɪt-/, coronal sonorant assimilation, and inter-dentalization of dentals. However, partial Funding: None assimilation occurs in the processes of nasal place assimilation, anticipatory labialization, and palatalization of plosives. Findings have revealed that assimilation occurs when the obligatory contour principle is violated on the place tier. Violation is then resolved by deletion of the place node in the leftmost matrix and by right-to-left spread of a feature from rightmost matrix to leftmost matrix. -

On Distinctive Features and Their Articulatory Implementation Author(S): Morris Halle Source: Natural Language & Linguistic Theory, Vol

On Distinctive Features and Their Articulatory Implementation Author(s): Morris Halle Source: Natural Language & Linguistic Theory, Vol. 1, No. 1 (1983), pp. 91-105 Published by: Springer Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4047515 Accessed: 14-04-2018 01:04 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Springer is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Natural Language & Linguistic Theory This content downloaded from 18.9.61.111 on Sat, 14 Apr 2018 01:04:26 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms MORRIS HALLE ON DISTINCTIVE FEATURES AND THEIR ARTICULATORY IMPLEMENTATION To the memory of Beatrice Hall 1. One of the first observations that students in an introductory phonetics course make is that the-gestures which the vocal tract executes in producing a given sound are readily analyzable into more elementary components or sub-gestures which, in combination with other sub-gestures, are also utilized in the production of other speech sounds. Thus, we find identical lip closure in each sound of the set [pbm], whereas the sounds in the set [kg] are all produced by the tongue body making contact with the velum.