Sanitation Nepal Will Tillett 01-2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal

SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Acknowledgements The completion of both this and the earlier feasibility report follows extensive consultation with the National Planning Commission, Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF, World Bank, and New ERA, together with members of the Statistics and Evidence for Policy, Planning and Results (SEPPR) working group from the International Development Partners Group (IDPG) and made up of people from Asian Development Bank (ADB), Department for International Development (DFID), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), WFP, and the World Bank. WFP, UNICEF and the World Bank commissioned this research. The statistical analysis has been undertaken by Professor Stephen Haslett, Systemetrics Research Associates and Institute of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, New Zealand and Associate Prof Geoffrey Jones, Dr. Maris Isidro and Alison Sefton of the Institute of Fundamental Sciences - Statistics, Massey University, New Zealand. We gratefully acknowledge the considerable assistance provided at all stages by the Central Bureau of Statistics. Special thanks to Bikash Bista, Rudra Suwal, Dilli Raj Joshi, Devendra Karanjit, Bed Dhakal, Lok Khatri and Pushpa Raj Paudel. See Appendix E for the full list of people consulted. First published: December 2014 Design and processed by: Print Communication, 4241355 ISBN: 978-9937-3000-976 Suggested citation: Haslett, S., Jones, G., Isidro, M., and Sefton, A. (2014) Small Area Estimation of Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commissions Secretariat, World Food Programme, UNICEF and World Bank, Kathmandu, Nepal, December 2014. -

TSLC PMT Result

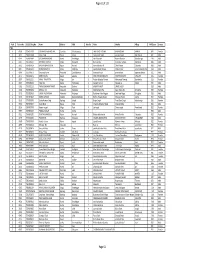

Page 62 of 132 Rank Token No SLC/SEE Reg No Name District Palika WardNo Father Mother Village PMTScore Gender TSLC 1 42060 7574O15075 SOBHA BOHARA BOHARA Darchula Rithachaupata 3 HARI SINGH BOHARA BIMA BOHARA AMKUR 890.1 Female 2 39231 7569013048 Sanju Singh Bajura Gotree 9 Gyanendra Singh Jansara Singh Manikanda 902.7 Male 3 40574 7559004049 LOGAJAN BHANDARI Humla ShreeNagar 1 Hari Bhandari Amani Bhandari Bhandari gau 907 Male 4 40374 6560016016 DHANRAJ TAMATA Mugu Dhainakot 8 Bali Tamata Puni kala Tamata Dalitbada 908.2 Male 5 36515 7569004014 BHUVAN BAHADUR BK Bajura Martadi 3 Karna bahadur bk Dhauli lawar Chaurata 908.5 Male 6 43877 6960005019 NANDA SINGH B K Mugu Kotdanda 9 Jaya bahadur tiruwa Muga tiruwa Luee kotdanda mugu 910.4 Male 7 40945 7535076072 Saroj raut kurmi Rautahat GarudaBairiya 7 biswanath raut pramila devi pipariya dostiya 911.3 Male 8 42712 7569023079 NISHA BUDHa Bajura Sappata 6 GAN BAHADUR BUDHA AABHARI BUDHA CHUDARI 911.4 Female 9 35970 7260012119 RAMU TAMATATA Mugu Seri 5 Padam Bahadur Tamata Manamata Tamata Bamkanda 912.6 Female 10 36673 7375025003 Akbar Od Baitadi Pancheswor 3 Ganesh ram od Kalawati od Kalauti 915.4 Male 11 40529 7335011133 PRAMOD KUMAR PANDIT Rautahat Dharhari 5 MISHRI PANDIT URMILA DEVI 915.8 Male 12 42683 7525055002 BIMALA RAI Nuwakot Madanpur 4 Man Bahadur Rai Gauri Maya Rai Ghodghad 915.9 Female 13 42758 7525055016 SABIN AALE MAGAR Nuwakot Madanpur 4 Raj Kumar Aale Magqar Devi Aale Magar Ghodghad 915.9 Male 14 42459 7217094014 SOBHA DHAKAL Dolakha GhangSukathokar 2 Bishnu Prasad Dhakal -

PMT Result 2075 List.Xlsx

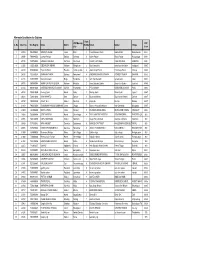

Alternate Candidates for Diploma Ward VDC/Municip PMT S. No. Token No SLC Reg No Name District Numbe Father Mother Village ality Score r 1 29169 7063002034 NIRMAYA SHAHI Jumla Birat 3 Prem Bahadur Shahi Kabita Shahi Barkotebada 968.1 2 30698 7468080053 Laxman Pariyar Bardiya Sorhawa 9 Kuber Pariyar Bhula Pariyar Puspanagar 968.1 3 30798 7374036042 RAMESH BOHARA Darchula Sharmauli 1 HARDEV BOHARA HIRA BOHARA SARMOLI 968.1 4 33026 7100271008 SIDDHA DHUNGANA Achham Mangalsen 5 Moti Ram jaishi manshara devi jaishi kudabasti 968.2 5 33372 6724003049 Rajendra Bulun Rasuwa Laharepouwa 4 Jawan Singh Bulun Charimaya Bulun dhunge 968.2 6 28436 7429362034 SHANKAR THAPA Bajhang Patadewal 8 KRISHNA BAHADUR THAPA SITADEVI THAPA BAYANA 968.3 7 33115 7429729007 niraj kumar karki Mugu Kotdanda 6 ram chandra karki raj kala karki luwai 968.4 8 30775 7369007044 MANOJ BAHADUR BUDHA Achham Risidaha 2 Amar Bahadur Budha Dewa Devi Budha Sanikhet 968.6 9 29144 6662015026 LOKENDRA BAHADUR SINGH Dailekh Chamunda 1 PURA SINGH KARNASHILA SHAHI Palta 968.7 10 30158 7459010030 khemraj Sarki Humla Maila 2 Manrup Sarki Dhauli Sarki tajakot 968.7 11 30416 7436010092 AJAY MAHATO Bara Dahiyar 6 Bayanath Mahato Bigni Sahani Malahi Dahiyar 968.7 12 30792 7462050002 JAGAT B. K Kalikot Ranchuli 2 Anipal bk Biuri bk Ratada 968.7 13 31833 7463020058 SURENDRA PRASAD SIMKHADE Jumla Dhapa 7 Ganesh Prasad Simkhade Ram Simkhade Bistabada 968.7 14 35029 7363004002 NISHA HAMAL Jumla Narakot 2 DHARMAL BDR HAMAL DHAN LAXMI HAMAL NARAKOT 968.7 15 28683 7359004084 SITA PHADERA Humla ShreeNagar -

Pray for Nepal

Pray for Nepal Humla Mugu Jumla Kalikot Dolpa Karnali, Mugu Greetings in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, Thank-You for committing to join with us to pray for the well-being of every village in our wonderful country. Jesus modeled his love for every village when he was going from one city and village to another with his disciples. Next, Jesus would mentor his disciples to do the same by sending them out to all the villages. Later, he would monitor the work of the disciples and the 70 as they were sent out two-by-two to all the villages. (Luke 8-10) But, how can we pray for the 3,984 VDCs in our Country? In the time of Nehemiah, his brother brought him news that the walls of Jerusalem were torn down. The wall represented protection, safety, blessing, and a future. Nehemiah prayed, fasted, and repented for the sins of the people. God answered Nehemiah’s prayers. The huge task to re-build the walls became possible through God’s blessings, each person building in front of their own houses, and the builders continuing even in the face of great persecution. For us, each village is like a brick in the wall. Let us pray for every village so that there are no holes in the wall. Each person praying for the villages in their respective areas would ensure a systematic approach so that all the villages of the state would be covered in prayer. Some have asked, “How do you eat an Elephant?” (How do you work on a giant project?) Others have answered, “One bite at a time.” (One step at a time - in small pieces). -

Notice Fifth Lot for All PMT Upto 2075.10.13 Selected & Alternate 2Nd Quintile

मत / / गतेको "गोरखाप दैनक "मा काशत सुचना अनुसार ावधक श ालयहमा डलोमा तहमा भनाx भएर वगत (चार पटक ) मा परयोजनाले सुचना काशन गदाx तो"कएको #यादभ$ आवेदन दताx गराउन छु टेका व(याथ*हले छा$वि-तृ आवेदन (Scholarship Application) फाराम परयोजनाको वेवसाइट www.event.gov.np बाट डाउनलोड गर2 भरेर श ालयले मा3णत गर2 प"रयोजना स%चवालय , वु'नगरमा मत /( /() काया* य समयभ दताx गराउनुहोला । सो5ह सुचना अनुसार डलोमा तहमा बाँक8 रहेका 99 कोटामा छा$वि-तमाृ छनोट गन: योजनका लाग पुवx काशन भएको पएमट2 यो;यता<म अनुसारको =>?@ जनाको नामावल2 । नोट : आवेदन फाराम प"रयोजनाका पुवx सुचनाह1 अनुसार दताx ग"रसकेका 2व3याथ5ह1ले भनु x नपन6 । Selected candidates for Diploma Ward Token VDC/Municipa PMT SN. SLC Reg No Name District Numb Father Mother Village No lity Score er 1 34871 7416018187 SRIJANA KUMARI MAHATO Siraha RamnagarMirchaiya 7 BINDESHWAR MAHATO SUDI RAM DULARI DEVI BAN KARYALAYA CHOWK884.5 2 28644 7259004015 DANSINGH ROKAYA Humla ShreeNagar 5 Barkhe Rokaya Gorikala Parki Rokaya Village 899 3 28719 7059004006 BANDANA PHADERA Humla ShreeNagar 4 Netra Phadera Pushi Phadera Phadera Gaun 905 4 32936 7224003027 JEEWAN KUMAR NEUPANE Rasuwa Dhaibung 4 Khem Raj Neupane Chet Kumari Neupane Katunje 907.5 5 32696 7063022017 KAMAL ROKAYA Jumla Lihi(Rara) 6 MAN BAHADUR ROKAYA MANMA ROKAYA LIHI 910 6 32817 7124013003 Ghyu Jyalmo Tamang Rasuwa Gatlang 8 Kawa Tamang Dawa Chamo Tamang Gre 910.5 7 29380 6562005014 Dipak Kumar Shahi Kalikot Jubika 6 Harsa Bahadur Shahi Padma Shahi Jubitha 911.7 8 30311 7372001067 DEEPA PARIYAR Doti Dipayal Silgadhi N.P.5 DILIP PARIYAR NIRMALA PARIYAR SILGADI 915.5 -

Project/Programme Proposal

DATE OF RECEIPT: ADAPTATION FUND PROJECT/PROGRAM ID: (For Adaptation Fund Board Secretariat Use Only) PROJECT/PROGRAMME PROPOSAL PART I: PROJECT/PROGRAMME INFORMATION PROJECT/PROGRAM CATEGORY: PROJECT COUNTRY/IES: NEPAL SECTOR/S: FOOD SECURITY AND AGRICULTURE TITLE OF PROJECT/PROGRAM: ADAPTING TO CLIMATE INDUCED THREATS TO FOOD PRODUCTION AND FOOD SECURITY IN THE KARNALI REGION OF NEPAL TYPE OF IMPLEMENTING ENTITY: MULTILATERAL IMPLEMENTING ENTITY IMPLEMENTING ENTITY: WORLD FOOD PROGRAM EXECUTING ENTITY/IES: MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT, SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY MINISTRY OF FEDERAL AFFAIRS AND LOCAL DEVELOPMENT AMOUNT OF FINANCING REQUESTED: USD 9,473,637 (over 3 years) 1 PROJECT BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT: Nepal is a landlocked country straddling the Himalayas and Tibetan plateau to the north and the dry Indian plains to the South. Its 147,181 square kilometres of land contain immense geophysical and ethnic diversity. Based on elevation, geology and terrain the country is divided in to five physiographic regions (figure below). On average it extends 885 kilometres east-west and 193 south-north direction. Altitudinal variation across this 193km is vast; from an average of 80m in the southern plains or Tarai to 8,848 in the northern High Himalayas. The Tarai plains occupy around 17% of the land, the hills around 68% and the high mountains around 15%.1 Administratively Nepal is divided into five development regions, 14 zones and 75 districts. In these 75 districts, there are 58 Municipalities and 3,915 Village Development Committees. Nepal’s population of 27 million is ethnically diverse. The major ethnic groups are mosaics of people originating from Indo-Aryan and Tibeto-Burmese races. -

RFP NO: (WFP/NEP/2018/CP001) This Request for Proposals

REQUEST FOR PROPOSALS (RFP) RFP NO: (WFP/NEP/2018/CP001) This Request for Proposals (RFP) is to establish operational partnerships with UN World Food Programme (WFP) for its Adaptation for Food Security Project (AFSP) in Jumla, Kalikot and Mugu districts, Karnali Province of Nepal. The United Nations World Food Programme (WFP) in Nepal invites your organization to submit proposals for the implementation of Adaptation Fund (AF) funded project entitled “Adapting to Climate- Induced Threats to Food Production and Food Security in the Karnali region of Nepal" in Jumla, Kalikot and Mugu districts. A. CLOSING DATE: Close of Business on 10 December 2018. B. GENERAL INFORMATION/TERMS AND CONDITIONS FOR PROPOSAL SUBMISSION a) We would like to draw your attention to the procedures established by WFP. Please carefully note and adhere to the terms and conditions mentioned in this document. b) This RfP is open to Nepali Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) working in Nepal. Local NGOs from the same project district will be given preference. c) Offers must include: Profile of the organization in the provided format/template. d) One organization is eligible to submit the proposal for only one district among Jumla, Kalikot and Mugu districts. e) The proposer will not be permitted to take advantage of any errors or omissions in this note. Should the proposer discover any errors or omissions, they must notify WFP accordingly. f) The proposals submitted by the proposers who meet the minimum eligibility criteria will only be considered for further evaluation. g) WFP reserves the right to reject any or all proposals without providing any reason whatsoever and has no obligation to accept any offer made. -

Food Security Bulletin 26

Nepal Food Security Bulletin Issue 26, October - December 2009 Situation Summary Figure 1. Percentage of population food insecure • The recent completion of the major harvest period of the year has improved the overall short-term food security situation 17.0% across the country. At a national level WFP household surveys revealed that food stocks and consumption levels have seen 16.5% an improvement since late last year when the harvest begun. • However, a number of districts in the Karnali and Far Western 16.0% Hills are suffering high or severe levels of food insecurity due to successive periods of drought, poor recent harvest, 15.5% insufficient supply of food in local markets and overall lack of economic opportunity. Over 50 percent of households 15.0% surveyed reported crop losses at 30-70 percent. • WFP Food for Work programming, which targeted 1.6 million 14.5% people in 2008/09, has significantly reduced the portion of Oct-Dec 08 Jan-Mar 09 Apr-Jun 09 Jul-Sep 09 Oct-Dec09 the total population which are highly and severely food Harvesting of the Summer crop and initiation of new WFP insecure. However, 145 VDCs across 12 districts of Nepal Food/Cash for Work programming have reduced the (mostly in the Mid– and Far-Western Regions but including 2 number of food insecure in the East in Sankhuwasabha) have been identified by the NeKSAP District Food Security Networks as being highly or severely food insecure. In these areas the estimated population which are unable to sustain their basic food consumption needs is 395,500. -

The Current Food Security Qtr

Nepal Food Security Bulletin Issue 25, July - October 2009 Situation Summary • The total number of food insecure people across Nepal is Figure 1. Percentage of population food insecure estimated to be 3.7 million, this represents approximately 16.4% of the rural population. WFP Nepal is feeding 1.6 17.0% million people which has had a significant impact on reducing 2009 winter drought this figure. 16.5% • July—August is typically a period of heightened food insecurity across Nepal. This year’s lean period was particularly severe in several areas of the country due to the 2008/09 winter 16.0% drought which led to reduced household food stocks and in the worst affected areas household food shortages. 15.5% • During the coming months, short term food security should continue to improve across most of Nepal as the current 15.0% harvest of summer crops (paddy, millet and maize) will be completed. However, the longer term outlook is that food security will decline within the next 6 months as summer crop 14.5% production at a national level is expected to be generally weak. Oct-Dec 09 Jan-Mar 09 Apr-Jun 09 Jul-Sep 09 Poor summer crop production is the result of late plantation (caused by late monsoon rains) combined with erratic and generally low rainfall during the monsoon. • Of the 476 households surveyed by WFP between July and September, summer crop losses of more than 30% have been experienced or are expected by more than 40% of households. Of critical concern is the situation in Bajura, Achham, Darchula, Jumla, Humla, Mugu, Dailekh, Rukum, and Taplejung where the main summer crops (paddy,millet and/or maize) have failed by 30-70% across multiple VDCs. -

Global Initiative on Out-Of-School Children

ALL CHILDREN IN SCHOOL Global Initiative on Out-of-School Children NEPAL COUNTRY STUDY JULY 2016 Government of Nepal Ministry of Education, Singh Darbar Kathmandu, Nepal Telephone: +977 1 4200381 www.moe.gov.np United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), Institute for Statistics P.O. Box 6128, Succursale Centre-Ville Montreal Quebec H3C 3J7 Canada Telephone: +1 514 343 6880 Email: [email protected] www.uis.unesco.org United Nations Children´s Fund Nepal Country Office United Nations House Harihar Bhawan, Pulchowk Lalitpur, Nepal Telephone: +977 1 5523200 www.unicef.org.np All rights reserved © United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) 2016 Cover photo: © UNICEF Nepal/2016/ NShrestha Suggested citation: Ministry of Education, United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), Global Initiative on Out of School Children – Nepal Country Study, July 2016, UNICEF, Kathmandu, Nepal, 2016. ALL CHILDREN IN SCHOOL Global Initiative on Out-of-School Children © UNICEF Nepal/2016/NShrestha NEPAL COUNTRY STUDY JULY 2016 Tel.: Government of Nepal MINISTRY OF EDUCATION Singha Durbar Ref. No.: Kathmandu, Nepal Foreword Nepal has made significant progress in achieving good results in school enrolment by having more children in school over the past decade, in spite of the unstable situation in the country. However, there are still many challenges related to equity when the net enrolment data are disaggregated at the district and school level, which are crucial and cannot be generalized. As per Flash Monitoring Report 2014- 15, the net enrolment rate for girls is high in primary school at 93.6%, it is 59.5% in lower secondary school, 42.5% in secondary school and only 8.1% in higher secondary school, which show that fewer girls complete the full cycle of education. -

RFP Documents Before the Proposal Submission Date

REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL RFP 01 F/Y 2066/67 Monitoring and Evaluation of the Basic Telecommunication Service Licensee of license no:- Basic 03 (Nepal Satellite Telecom Pvt. Ltd) October 2009 RFA Selection of Consultant Basic-03 2/ 73 Section 1. Letter of Invitation Nepal Telecommunications Authority Bluestar Office Complex, Tripureshwor, Kathmandu Dear Mr./Ms 1. Nepal Telecommunications Authority (NTA) invites proposals to provide the consulting services on Monitoring and Evaluation of the Basic Telecommunication Service Licensee of license no:- Basic 03 (Nepal Satellite Telecom Pvt. Ltd) with the objective to supervise the implementation of the Roll out Obligation of the Licensee. More details on the services are provided in the Terms of References . 2. A firm/consultant will be selected under Least Cost Selection (LCS) method and procedures described in this RFP 3. The RFP includes the following documents: Section 1 - Letter of Invitation Section 2 - Instructions to Consultants (including Data Sheet) Section 3 - Technical Proposal - Standard Forms Section 4 - Financial Proposal - Standard Forms Section 5 - Terms of Reference Section 6 - Standard Forms of Contract 4. Please inform us in writing at the following address before the closing date mentioned in this RFP (a) Whether you will submit a proposal alone or in association which shall be in the form of a Joint Venture with joint and several liabilities. 5. NTA reserves all rights to accept or reject any or all proposals without assigning any reason whatsoever. Yours sincerely, _____________________________ Mr. Bhesh Raj Kanel Chairman, Nepal Telecommunications Authority Date :- 5th November 2009 RFA Selection of Consultant Basic-03 3/ 73 Section 2. -

Mcpms Result of Lbs for FY 2065-66

Government of Nepal Ministry of Local Development Secretariat of Local Body Fiscal Commission (LBFC) Minimum Conditions(MCs) and Performance Measurements (PMs) assessment result of all LBs for the FY 2065-66 and its effects in capital grant allocation for the FY 2067-68 1.DDCs Name of DDCs receiving 30 % more formula based capital grant S.N. Name PMs score Rewards to staffs ( Rs,000) 1 Palpa 90 150 2 Dhankuta 85 150 3 Udayapur 81 150 Name of DDCs receiving 25 % more formula based capital grant S.N Name PMs score Rewards to staffs ( Rs,000) 1 Gulmi 79 125 2 Syangja 79 125 3 Kaski 77 125 4 Salyan 76 125 5 Humla 75 125 6 Makwanpur 75 125 7 Baglung 74 125 8 Jhapa 74 125 9 Morang 73 125 10 Taplejung 71 125 11 Jumla 70 125 12 Ramechap 69 125 13 Dolakha 68 125 14 Khotang 68 125 15 Myagdi 68 125 16 Sindhupalchok 68 125 17 Bardia 67 125 18 Kavrepalanchok 67 125 19 Nawalparasi 67 125 20 Pyuthan 67 125 21 Banke 66 125 22 Chitwan 66 125 23 Tanahun 66 125 Name of DDCs receiving 20 % more formula based capital grant S.N Name PMs score Rewards to staffs ( Rs,000) 1 Terhathum 65 100 2 Arghakhanchi 64 100 3 Kailali 64 100 4 Kathmandu 64 100 5 Parbat 64 100 6 Bhaktapur 63 100 7 Dadeldhura 63 100 8 Jajarkot 63 100 9 Panchthar 63 100 10 Parsa 63 100 11 Baitadi 62 100 12 Dailekh 62 100 13 Darchula 62 100 14 Dang 61 100 15 Lalitpur 61 100 16 Surkhet 61 100 17 Gorkha 60 100 18 Illam 60 100 19 Rukum 60 100 20 Bara 58 100 21 Dhading 58 100 22 Doti 57 100 23 Sindhuli 57 100 24 Dolpa 55 100 25 Mugu 54 100 26 Okhaldhunga 53 100 27 Rautahat 53 100 28 Achham 52 100