The Story of Comfort Air Conditioning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Apple Blossom Times

Town of Newfane Historical Society’s Apple Blossom Times Since 1975 Summer 2021 rental info., date Inside This Issue Summertime’s in the air availability and President’s Letter From the desk of our President more. Minute History Hello friends- We have made it through winter and now If you are reading this, we head full speed into warmer days, thank goodness! May 16: Drive-Thru dear member, know that all of us at the Chowder Fundraiser With uncertainty still in the air concerning the Newfane Historical pandemic, we are moving our 44th Apple Blossom Member Update Society appreciate Festival to 2022. We won’t leave you hanging, however, your support, and Summer Fun Fact as we are doing a drive-thru chowder fundraiser on anxiously await for May 16. It is a first-come, first-serve basis, so don’t History of the Electric Fan the days when we’ll miss out! Art Gladow’s famous chicken chowder all come together WNY Native Etymologies has always been a staple of our apple festivals, and again to celebrate is the first food to sell out annually. So swing by that Support our Historial Society local history in person. As I sign off, I will leave you Sunday for some chowder and to say hello to some of our with this, to put a smile on your face. Recipe Rewind hardworking trustees and volunteers! What do ghosts like to eat in the summer? Calendar With warmer weather upon us, I’d also like to I Scream. remind everyone that the Van Horn Mansion and Country Village are available for private rentals. -

A History of Heat in the Subtropical American South

Mississippi State University Scholars Junction Theses and Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1-1-2017 By Degree: A History of Heat in the Subtropical American South Jason Hauser Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsjunction.msstate.edu/td Recommended Citation Hauser, Jason, "By Degree: A History of Heat in the Subtropical American South" (2017). Theses and Dissertations. 943. https://scholarsjunction.msstate.edu/td/943 This Dissertation - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Scholars Junction. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholars Junction. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Template A v3.0 (beta): Created by J. Nail 06/2015 By degree: A history of heat in the subtropical American south By TITLE PAGE Jason Hauser A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Mississippi State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in United States History in the Department of History Mississippi State, Mississippi August 2017 Copyright by COPYRIGHT PAGE Jason Hauser 2017 By degree: A history of heat in the subtropical American south By APPROVAL PAGE Jason Hauser Approved: ____________________________________ James C. Giesen (Major Professor) ____________________________________ Mark D. Hersey (Minor Professor) ____________________________________ Anne E. Marshall (Committee Member) ____________________________________ Alan I Marcus (Committee Member) ____________________________________ Alexandra E. Hui (Committee Member) ____________________________________ Stephen C. Brain (Graduate Coordinator) ____________________________________ Rick Travis Dean College of Arts and Sciences Name: Jason Hauser ABSTRACT Date of Degree: August 11, 2017 Institution: Mississippi State University Major Field: United States History Major Professor: James C. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination

NPS Form 10-900 (3-82) OMB No. 1024-0018 Expires 10-31-87 United States Department off the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Places received Inventory Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections____________ 1. Name historic Rockefeller Center and or common 2. Location Bounded by Fifth Avenue, West 48th Street, Avenue of the street & number Americas, and West 51st Street____________________ __ not for publication city, town New York ___ vicinity of state New York code county New York code 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public x occupied agriculture museum x building(s) x private unoccupied x commercial park structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible _ x entertainment religious object in process x yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military other: 4. Owner of Property name RCP Associates, Rockefeller Group Incorporated street & number 1230 Avenue of the Americas city, town New York __ vicinity of state New York 10020 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Surrogates' Court, New York Hall of Records street & number 31 Chambers Street city, town New York state New York 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Music Hall only: National Register title of Historic Places has this property been determined eligible? yes no date 1978 federal state county local depository for survey records National Park Service, 1100 L Street, NW ^^ city, town Washington_________________ __________ _ _ state____DC 7. Description Condition Check one Check one x excellent deteriorated unaltered x original s ite good ruins x altered moved date fair unexposed Describe the present and original (iff known) physical appearance The Rockefeller Center complex was the final result of an ill-fated plan to build a new Metropolitan Opera House in mid-town Manhattan. -

Air Conditioning and Refrigeration Chronology

Air Conditioning and Refrigeration C H R O N O L O G Y Significant dates pertaining to Air Conditioning and Refrigeration revised May 4, 2006 Assembled by Bernard Nagengast for American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air Conditioning Engineers Additions by Gerald Groff, Dr.-Ing. Wolf Eberhard Kraus and International Institute of Refrigeration End of 3rd. Century B.C. Philon of Byzantium invented an apparatus for measuring temperature. 1550 Doctor, Blas Villafranca, mentioned process for cooling wine and water by adding potassium nitrate About 1597 Galileo’s ‘air thermoscope’ Beginning of 17th Century Francis Bacon gave several formulae for refrigeration mixtures 1624 The word thermometer first appears in literature in a book by J. Leurechon, La Recreation Mathematique 1631 Rey proposed a liquid thermometer (water) Mid 17th Century Alcohol thermometers were known in Florence 1657 The Accademia del Cimento, in Florence, used refrigerant mixtures in scientific research, as did Robert Boyle, in 1662 1662 Robert Boyle established the law linking pressure and volume of a gas a a constant temperature; this was verified experimentally by Mariotte in 1676 1665 Detailed publication by Robert Boyle with many fundamentals on the production of low temperatures. 1685 Philippe Lahire obtained ice in a phial by enveloping it in ammonium nitrate 1697 G.E. Stahl introduced the notion of “phlogiston.” This was replaced by Lavoisier, by the “calorie.” 1702 Guillaume Amontons improved the air thermometer; foresaw the existence of an absolute zero of temperature 1715 Gabriel Daniel Fahrenheit developed mercury thermoneter 1730 Reamur introduced his scale on an alcohol thermometer 1742 Anders Celsius developed Centigrade Temperature Scale, later renamed Celsius Temperature Scale 1748 G. -

Shadow Boxing’ M

, ............ ‘Sv^.'’v;,a,3|5 ■:' ■ AVBRAOB DAILT oaODLATION tor On Hamm mt M y . U M itn WEAUndv IP!: I e l 0. S. WaMOaf 5,769 Bartferd the AodR Hnabet mt BassOy eiondy, oasttaoea eeel 3^. Berese e« Obeelstleee. BigM sad Friday. MANCHESTER— A aT Y OP VILLAGE CHARM Substandards of Regular $1JI9 VOL. LV., NO. 281 A dverriH ig SB Fagd ['MmUkif f f m Soft CftpeakiH aad 4-Year Guaranteed Fine Weave MANCHESTER. CONN, THURSDAY, AUGUST *7, 1936 (TWELVE PAGES) PRICE THREE Four-Year Guaranteed Deealda Percale SHEETS PILLOW GLOVES Special Dollar Day Only! WAR SECRETARY DERN AVERS FRANCE, CAUCUSES CAST CASES ROOSEVELT ACCUSED Cdon and Natural CARNIVAL $ 1 .0 0 each 42x36” — 45x36” BRITAIN HAVE BUTDMUGHT 'Tan. Sizes 6 to l\'i. $ .0 0 pr. OF Our regular 29c percale pillow case Valuee to |L05. \ Sizes 68x99", 68x108”, 72x99”, that ia so much liner than caaee made FAIIB SPAIN 72x108”, 81x99”. from sheeting. Regular 29c each. DIES IN WASHINGTON ONSTMSCENE Thee* sheeU M the aanie high quiOlty u our Rale's Flnemun and are OF ‘SHADOW BOXING’ M. K. M. Pore Silk Full Fashioned g u a r a n ^ for at least four year# wear. Slight mia-weavea or oU tpoU that to not Impair the wearing quallUes. Sheets have advanced considerably dur- for Member of Roosevelt Cabk Prieto, Socialist ^ o n g Harmony Roles Eicept in tag the last tlx weeks and It will pay you to atock up at this low price. $ 1.00 r Secretary of W a r Passes Away. net Passes Away Foflow’ Man,’’ Calls ffis-^lorntry Few Spots; Some Dele BY KNOX IN SPEEC HOSIERY Fall felts in black, brown, Beautsnrest or Innerspring: 36” Past Color New Pall A B C navy, green and wine. -

Change and Technology in the United States

Change and Technology in the United States A Resource Book for Studying the Geography and History of Technology Stephen Petrina Including: 12 Printable Maps Showing 700+ Inventions from 1787-1987 279 Technological Events 32 Graphs and Tables of Historical Trends 5 Timelines of Innovation and Labor with Pictures Plus: 3 Tables for Cross-Referencing Standards 50 Links to WWW Resources and Portals 50+ Resource Articles, CDs, Books & Videos Change and Technology in the United States A Resource Book for Studying the Geography and History of Technology Dr. Stephen Petrina Copyright © 2004 by Stephen Petrina Creative Commons License Copies of this document are distributed by: Council on Technology Teacher Education (http://teched.vt.edu/ctte/HTML/Research1.html) International Technology Education Association 1914 Association Drive, Suite 201 Reston, VA 20191-1531 Phone (703) 860-2100 Fax (703) 860-0353 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.iteaconnect.org Note: Cover illustration— "Building New York City's Subway"— is from Scientific American 15 July 1915. Wright Plane Drawing reproduction courtesy of the National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution. Change and Technology in the United States Preface This project is the result of a project undertaken in my graduate program at the University of Maryland during the late 1980s. When I began, I did not fully realize the scale of the challenge. The research itself was extremely intimidating and time-consuming. It took me a few years to figure out what resources were most helpful in integrating the geography and history of technology. I completed eights maps in 1987 and did a fair amount of writing at the same time. -

Rockefeller Center Complex Master Plan and Exterior Rehabilitations New York, New York

Rockefeller Center Complex Master Plan and Exterior Rehabilitations New York, New York Developed for the purpose of planning maintenance and capital improvement projects, Hoffmann National Trust for Architects’ Exterior Rehabilitation Master Plan for Rockefeller Center encompassed the nineteen Historic Preservation buildings of John D. Rockefeller Jr.’s 22-acre “city within a city.” The buildings are subject not only to Honor Award New York City Department of Buildings regulations, including New York City Local Law 10 of 1980 GE Building at Rockefeller and Local Law 11 of 1998 (LL10/LL11), but also to Landmark Commission restrictions, making Center - Restoration rehabilitation planning particularly challenging. Hoffmann Architects’ Master Plan addressed these considerations, while achieving even budgeting across the years. The award-winning rehabilitation program included facade and curtain wall restoration, roof replacements, waterproofing, and historic preservation for this National Historic Landmark and centerpiece of New York City. In conjunction with the Master Plan, Hoffmann Architects developed specific rehabilitation solutions for the Center’s structures, including: GE Building, Sculpture Restoration and Building Envelope Rehabilitation Radio City Music Hall, Roof Replacement and Facade Restoration La Maison Francaise and The British Empire Building, Facade Evaluations and Cleaning Channel Gardens and Lower Plaza/Skating Rink, Survey and Rehabilitation Design International Building, Facade Restoration and Roof Replacement Simon -

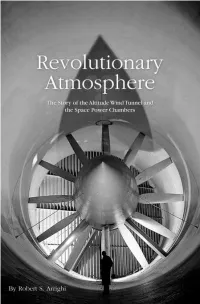

The Altitude Wind Tunnel Stands Up

Revolutionary Atmosphere Revolutionary Atmosphere The Story of the Altitude Wind Tunnel and the Space Power Chambers By Robert S. Arrighi National Aeronautics and Space Administration NASA History Division Office of Communications NASA Headquarters Washington, DC 20546 SP−2010−4319 April 2010 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Arrighi, Robert S., 1969- Revolutionary atmosphere: the story of the Altitude Wind Tunnel and the Space Power Chambers / by Robert S. Arrighi. p. cm. - - (NASA SP-2010-4319) “April 2010.” Includes bibliographical references. 1. Altitude Wind Tunnel (Laboratory)—History. 2. Space Power Chambers (Laboratory)—History. 3. Aeronautics—Research—United States—History. 4. Space vehicles—United States—Testing—History. I. Title. TL567.W5A77 2010 629.46’8—dc22 2010018841 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20401–0001 ISBN 978-0-16-085641-9 Contents Contents Preface ...................................................................................................................ix Acknowledgments ...............................................................................................xvii Chapter 1 Premonition: The Need for an Engine Tunnel (1936−1940) ...........................3 “I Have Seen Nothing Like Them in America” ........................................4 Evolution of the Wind Tunnel ..................................................................5 -

Megablock Urbanism Rockefeller Center Reconsidered New York, NY USA

Columbia University GSAPP AAD Summer 2015 Critic: Jeffrey Johnson [email protected] TA: Jiteng Yang [email protected] Megablock Urbanism Rockefeller Center Reconsidered New York, NY USA Rockefeller Center - Original Design in 1931 Image: wirednewyork.com Intro: The world continues to urbanize, in many regions at an astonishing pace, and we as architects must find ways to intervene in its physical metamorphosis. We are for the first time in history more urban than rural. Existing cities are expanding and new ones are being formed without historic precedent. How we continue to urbanize is of huge consequence. And, how we understand this phenomenon is critical to our ability to participate in the future urbanization of the world. This means we must invent new ways of thinking about cities and be agile enough to continuously modify and/or discard even the most recently developed theories and strategies. What possible socially and ecologically sustainable solutions can be invented for accommodating future urban growth? What role does architecture play in these newly formed megacities? 1 AAD Studio Summer 2015 - Johnson Superblock / Megablock: For many cities around the world, large-scale superblock development provides the default solution for accommodating urban growth. Superblocks, in their contemporary form, are byproducts of modernism – from Le Corbusier; to Soviet microrayons; to Lúcio Costa and Oscar Niemeyer’s Brasilia; to Mao’s danwei (factory units); to Steven Holl’s Linked Hybrid in Beijing. Varying in size from 8 hectares to over 50 hectares, with populations from 1,000’s to over 100,000, superblocks are spatial instruments with social, cultural, environmental, and economic implications, operating between the scales of architecture and the city. -

The University of Chicago Exquisite Schemes: The

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO EXQUISITE SCHEMES: THE AESTHETICS OF EXCESS IN THE LATE BRITISH EMPIRE, 1890-1930 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE BY JACOB HARRIS CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2020 Copyright 2020 by Jacob Harris. All rights reserved. ii Table of Contents List of Figures.................................................................................................................................................... iv Acknowledgements........................................................................................................................................... vi Abstract.............................................................................................................................................................. ix Introduction........................................................................................................................................................ 1 I. The arts of excess...................................................................................................................................... 1 II. Excess and empire in the fin-de-siècle and the early 20th century……......................................... 10 III. Method................................................................................................................................................... 15 IV. Chapter outline.................................................................................................................................... -

Imaging Axis Terror: War Propaganda and the 1943 “The Nature of the Enemy” Exhibition at Rockefeller Center

Imaging Axis Terror: War Propaganda and the 1943 “The Nature of the Enemy” Exhibition at Rockefeller Center Christof Decker1 Abstract In the summer of 1943, the Office of War Information (OWI) staged an exhibition titled “The Nature of the Enemy” at Rockefeller Center in New York City. It in- cluded huge photo-murals showing the destruction and displacement caused by the global conflict of World War II and six scenic installations depicting the cruel practices of the Axis powers. In this essay, I analyze the exhibition, which was de- signed by OWI Deputy Director Leo Rosten, as an instance of propaganda, relat- ing it to a series of posters on the same topic produced at the OWI by the Ameri- can artist Ben Shahn, but never shown to the public. Rosten’s exhibition depicted the enemy’s actions and alleged nature in a prestigious urban location and pro- vocative style, combining elements of instruction with thrilling entertainment. I argue that it signified an important yet ambiguous and contradictory attempt to represent the horrors of war from a “comfortable distance.” While Shahn’s poster series aimed for empathetic identification with the victims of terror, Rosten’s ex- hibition promised the vicarious experience of cruelty through the juxtaposition of enemy statements and installations depicting scenes of violence. 1 Fighting the “Nazi Method” In the early months of 1943, the domestic branch of the U.S.-Amer- ican Office of War Information (OWI) worked on various projects to inform the public about the war. While the majority of these campaigns dealt with practical, war-related matters such as keeping military infor- mation secret, preserving food, recycling precious raw materials, and intensified efforts in war production, other campaigns addressed larger ideological issues. -

A Self Guided Tour

Things to See in Midtown Manhattan | A Self Guided Tour Midtown Manhattan Self-Guided Tour Empire State Building Herald Square Macy's Flagship Store New York Times Times Square Bank of America Tower Bryant Park former American Radiator building New York Public Library Grand Central Terminal Chanin Building Chrysler Building United Nations Headquarters MetLife Building Helmsley Building Waldorf Astoria New York Saks Fifth Avenue St. Patrick's Cathedral Rockefeller Center The Museum of Modern Art Carnegie Hall Trump Tower Tiffany & Co. Bloomingdale's Serendipity 3 Roosevelt Island Tram Self-guided Tour of Midtown Manhattan by Free Tours By Foot Free Tours by Foot's Midtown Manhattan Self-Guided Tour If you would like a guided experience, we offer several walking tours of Midtown Manhattan. Our tours have no cost to book and have a pay-what-you-like policy. This tour is also available in an anytime, GPS-enabled audio tour . Starting Point: The tour starts at the Empire State Building l ocated at 5th Avenue between 33rd and 34th Streets. For exact directions from your starting point use this helpful G oogle directions tool . By subway: 34th Street-Herald Square (Subway lines B, D, F, N, Q, R, V, W) or 33rd Street Station by 6 train. By ferry: You can now take a ferry to 34th Street and walk or take the M34 bus to 5th Avenue. Read our post on the East River Ferry If you are taking one of the many hop-on, hop-off bus tours such as Big Bus Tours or Grayline , all have stops at the Empire State Building.