The Philosophy and Jurisprudence of Chief Justice Roberts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reckless Caution: the Perils of Judicial Minimalism

RECKLESS CAUTION: THE PERILS OF JUDICIAL MINIMALISM Tara Smith* ABSTRACT Judicial Minimalism is the increasingly popular view that judges decide cases properly to the extent that they minimize their own imprint on the law by meticulously assessing “one case at a time,” ruling on narrow and shallow grounds, eschewing broader theories, and altering entrenched legal practices only incremen- tally. Minimalism’s ascendancy across the political spectrum, be- ing embraced by advocates of both right-wing and left-wing ide- ologies, is touted as a sign of its appropriate value-neutrality. This paper argues that such sought-after neutrality is, in fact, untenable. While others have objected to some of Minimalism’s specific tenets, critics have missed its more fundamental failing: it is an incoherent concept. On analysis, Minimalism’s several planks and rationales prove mutually contradictory and, corre- spondingly, offer conflicting guidance to judges. Thus the reason that Minimalism can appeal to people of such disparate substan- tive views is that in practice, it is merely a placeholder invoked to * Many people have offered helpful discussion of the ideas developed in this paper or feedback on earlier drafts. I am grateful to audiences at Oxford’s Uehiro Center and the University of Virginia, and in particular to Tom Bowden, Onkar Ghate, Wesley Hottot, Loren Lomasky, Al Martinich, Matt Miller, Adam Mossoff, Matt O’Brien, Greg Salmieri, Julian Savulescu, John Simmons, and Kevin Stuart. 347 348 New York University Journal of Law & Liberty [Vol. 5:347 sanction a grab-bag of desiderata rather than a distinctive method of decision-making that offers genuine guidance. -

Social Studies –American History: the Founding Principles, Civics and Economics Course

Appendix A: American History: The Founding Principles, Civics and Economics This appendix contains additions made to the North Carolina Essential Standards for Civics and Economics pursuant to the North Carolina General Assembly passage of The Founding Principles Act (SL 2011-273). This document is organized as follows: an introduction that describes the intent of the course and a set of standards that establishes the expectation of what students should understand, know, and be able to do upon successful completion of the course. There are ten essential standards for this course, each with more specific clarifying objectives. The name of the course has been changed to American History: The Founding Principles, Civics and Economics and the last column has been added to show the alignment of the standards to the Founding Principles Act. 6 North Carolina Essential Standards Social Studies –American History: The Founding Principles, Civics and Economics Course American History: The Founding Principles, Civics and Economics has been developed as a course that provides a framework for understanding the basic tenets of American democracy, practices of American government as established by the United States Constitution, basic concepts of American politics and citizenship and concepts in macro and micro economics and personal finance. The essential standards of this course are organized under three strands – Civics and Government, Personal Financial Literacy and Economics. The Civics and Government strand is framed to develop students’ increased understanding of the institutions of constitutional democracy and the fundamental principles and values upon which they are founded, the skills necessary to participate as effective and responsible citizens and the knowledge of how to use democratic procedures for making decisions and managing conflict. -

The Influence of Jurisprudential Inquiry 1

Running Head: THE INFLUENCE OF JURISPRUDENTIAL INQUIRY 1 The Influence of Jurisprudential Inquiry Learning Strategies and Logical Thinking Ability towards Learning of Civics in Senior High School (SMA) 1Hernawaty Damanik 2I Nyoman S. Degeng 2Punaji Setyosari 2I Wayan Dasna 1Open University; State University of Malang 2State University of Malang Author Note Hernawaty Damanik is senior lecturer at Open University, Malang, and student of Graduate Program in Education Technology State University of Malang. I Nyoman S. Degeng and Punaji Setyosari are professors at Graduate Program State University of Malang. I Wayan Dasna is senior lecturer at Graduate Program State University of Malang Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to [email protected] THE INFLUENCE OF JURISPRUDENTIAL INQUIRY 2 THE INFLUENCE OF JURISPRUDENTIAL INQUIRY LEARNING STRATEGIES AND LOGICAL THINKING ABILITY TOWARDS LEARNING OF CIVICS SENIOR HIGH SCHOOL (SMA) Abstract Pancasila and Citizenship Education (Civics) is one of many other school subjects emphasizing on value and moral education in order to form multicultural Indonesian citizens who appreciate the culture of plural communities. The learning of PPKn (civics) should be designed and developed through a thorough strategy in accordance with its aims and materials to create students with critical, argumentative, and logical thinking ability. The learning of civics has not been totally carried out on the tract where teachers are dominantly active in the class while students just do memorizing and reading, less of joyfull learning, and become “text-bookish”. One of many other strategies to succeed innovative, constructive, and relevant learning in accordance with the thinking ability of Senior High School students is through jurisprudential inquiry. -

Learn About the United States Quick Civics Lessons for the Naturalization Test

Learn About the United States Quick Civics Lessons for the Naturalization Test M-638 (rev. 02/19) Learn About the United States: Quick Civics Lessons Thank you for your interest in becoming a citizen of the United States of America. Your decision to apply for IMPORTANT NOTE: On the naturalization test, some U.S. citizenship is a very meaningful demonstration of answers may change because of elections or appointments. your commitment to this country. As you study for the test, make sure that you know the As you prepare for U.S. citizenship, Learn About the United most current answers to these questions. Answer these States: Quick Civics Lessons will help you study for the civics questions with the name of the official who is serving and English portions of the naturalization interview. at the time of your eligibility interview with USCIS. The USCIS Officer will not accept an incorrect answer. There are 100 civics (history and government) questions on the naturalization test. During your naturalization interview, you will be asked up to 10 questions from the list of 100 questions. You must answer correctly 6 of the 10 questions to pass the civics test. More Resources to Help You Study Applicants who are age 65 or older and have been a permanent resident for at least 20 years at the time of Visit the USCIS Citizenship Resource Center at filing the Form N-400, Application for Naturalization, uscis.gov/citizenship to find additional educational are only required to study 20 of the 100 civics test materials. Be sure to look for these helpful study questions for the naturalization test. -

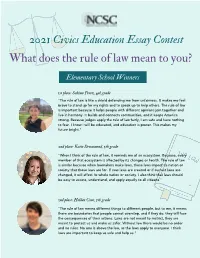

What Does the Rule of Law Mean to You?

2021 Civics Education Essay Contest What does the rule of law mean to you? Elementary School Winners 1st place: Sabina Perez, 4th grade "The rule of law is like a shield defending me from unfairness. It makes me feel brave to stand up for my rights and to speak up to help others. The rule of law is important because it helps people with different opinions join together and live in harmony. It builds and connects communities, and it keeps America strong. Because judges apply the rule of law fairly, I am safe and have nothing to fear. I know I will be educated, and education is power. This makes my future bright." 2nd place: Katie Drummond, 5th grade "When I think of the rule of law, it reminds me of an ecosystem. Because, every member of that ecosystem is affected by its changes or health. The rule of law is similar because when lawmakers make laws, those laws impact its nation or society that those laws are for. If new laws are created or if current laws are changed, it will affect its whole nation or society. I also think that laws should be easy to access, understand, and apply equally to all citizens." 3nd place: Holden Cone, 5th grade "The rule of law means different things to different people, but to me, it means there are boundaries that people cannot overstep, and if they do, they will face the consequences of their actions. Laws are not meant to restrict, they are meant to protect us and make us safer. -

Rethinking Judicial Minimalism: Abortion Politics, Party Polarization, and the Consequences of Returning the Constitution to Elected Government Neal Devins

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 69 | Issue 4 Article 3 5-2016 Rethinking Judicial Minimalism: Abortion Politics, Party Polarization, and the Consequences of Returning the Constitution to Elected Government Neal Devins Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation Neal Devins, Rethinking Judicial Minimalism: Abortion Politics, Party Polarization, and the Consequences of Returning the Constitution to Elected Government, 69 Vanderbilt Law Review 935 (2019) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol69/iss4/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rethinking Judicial Minimalism: Abortion Politics, Party Polarization, and the Consequences of Returning the Constitution to Elected Government Neal Devins* IN TROD U CTION ............................................................................... 935 I. MINIMALISM THEORY AND ABORTION ................................. 939 II. WHAT ABORTION POLITICS TELLS US ABOUT JUDICIAL M INIMALISM ........................................................ 946 A . R oe v. W ade ............................................................. 947 B . From Roe to Casey ................................................... 953 C. Casey and Beyond .................................................. -

Elena Kagan Can't Say That: the Sorry State of Public Discourse Regarding Constitutional Interpretation

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Washington University St. Louis: Open Scholarship Washington University Law Review Volume 88 Issue 2 2010 Elena Kagan Can't Say That: The Sorry State of Public Discourse Regarding Constitutional Interpretation Neil J. Kinkopf Georgia State University College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Judges Commons Recommended Citation Neil J. Kinkopf, Elena Kagan Can't Say That: The Sorry State of Public Discourse Regarding Constitutional Interpretation, 88 WASH. U. L. REV. 543 (2010). Available at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview/vol88/iss2/7 This Commentary is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ELENA KAGAN CAN’T SAY THAT: THE SORRY STATE OF PUBLIC DISCOURSE REGARDING CONSTITUTIONAL INTERPRETATION NEIL J. KINKOPF MEMORANDUM FOR THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES From: Ray L. Politik, Counsel to the President Re: Proposed Statement of Elena Kagan to the U.S. Senate, Committee on the Judiciary, on her nomination to be an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States Date: June 2010 _______________________________________________________ I have reviewed the draft statement that Elena Kagan has proposed submitting to the Senate Judiciary Committee.1 In this statement, Dean Kagan seeks to educate the Judiciary Committee and the American people to think differently about the enterprise of constitutional interpretation. -

“Equal Right to the Poor” Richard M

“Equal Right to the Poor” Richard M. Re† By law, federal judges must swear or affirm that they will “do equal right to the poor and to the rich.” This frequently overlooked oath, which I call the “equal right principle,” has historical roots dating back to the Bible and entered US law in a statute passed by the First Congress. Today, the equal right principle is often understood to require only that judges faithfully apply other laws. But that reading, like the idea that the rich and poor are equally barred from sleeping under bridges, is questionable in light of the equal right principle’s text, context, and history. This Article argues that the equal right principle supplies at least a plausible basis for federal judges to consider substantive economic equality when implement- ing underdetermined sources of law. There are many implications. For example, the equal right principle suggests that federal courts may legitimately limit the poor’s disadvantages in the adjudicative and legislative processes by expanding counsel rights and interpreting statutes with an eye toward economically vulnera- ble groups. The equal right principle should also inform what qualifies as a com- pelling or legitimate governmental interest within campaign finance jurispru- dence, as well as whether to implement “underenforced” equal protection principles. More broadly, the equal right principle should play a more central role in constitutional culture. The United States is unusual in that its fundamental law is relatively silent on issues of economic equality. The equal right principle can fill that void by providing a platform for legal and public deliberation over issues of wealth inequality. -

ACTL Mourns Loss of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg

ACTL MOURNS THE LOSS OF ASSOCIATE JUSTICE RUTH BADER GINSBURG NEWPORT BEACH, CALIF. (September 19, 2020) - The American College of Trial Lawyers (ACTL) mourns the loss of Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States Ruth Bader Ginsburg, a trailblazing advocate, a meticulous jurist, a true patriot, and an Honorary Fellow of the College. Chief Justice of the U.S. John Roberts said, “She was a justice of historic stature and a tireless and resolute champion of justice.” Recently Justice Ginsburg joined Justices Alito and Breyer, and jurists from the United Kingdom, in a U.K.–U.S. legal exchange sponsored by the ACTL to discuss common issues in support of the rule of law and access to justice, even across international boundaries. “Her commentary during those days together was both insightful and inspiring. In an era when uncertainty is so much a part of our national narrative, hers was a call to our ‘better angels’ and a meaningful challenge at a time that calls for equal protection to all persons and causes,” said ACTL President Douglas R. Young. The College commends Justice Ginsburg’s career as an accomplished and courageous trial and appellate lawyer while in private practice and a person of deep faith committed to the best our countries have to offer. The world is enriched by her example. We are humbled and inspired by her spirit. # # # About the American College of Trial Lawyers The American College of Trial Lawyers is composed of preeminent members of the trial bar from the United States and Canada and is recognized as the leading trial lawyer’s organization in both countries. -

Kagan-Issues Privilege-June-301.Pdf

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES BLOG SCOTUSBLOG SCOTUSblog Briefing Paper Elena Kagan – Privilege and Release of Kagan Documents June 30, 2010 I. Summary and Our Take Shortly after Elena Kagan was nominated on May 10, 2010, the Senate Judiciary Committee set June 28, 2010 as the first day of an estimated four days of confirmation hearings. This meant that there were forty-nine days between the nomination and start of the hearings (as compared to forty-eight for Sonia Sotomayor last summer). The Committee almost immediately began the process of requesting documents related to Kagan’s service in both the Clinton and Obama Administrations. Senators, the Republicans in particular, hoped that these documents might shed new light on her judicial philosophy in a way that her relatively sparse written record had not. Under the Presidential Records Act (PRA) and Executive Order 13489b, all documents requested by the Judiciary Committee must be searched for, pulled, and read by archivists, who vet each page for possible legal restrictions. Then, representatives for both Presidents Clinton and Obama have the right to read and review documents related to their respective administrations and get the final say on which documents (or pages of documents) are released or withheld. Additionally, as the incumbent administration, Obama’s representatives have the right to review the documents of its own administration as well as those from the Clinton administration (Clinton representatives are not permitted to review documents from the Obama administration). When Kagan was nominated, it was unclear what documents, if any, the Obama or Clinton Administrations might choose to withhold, or whether there was a potential bombshell within these documents that might put the nomination in jeopardy. -

"Public Service Must Begin at Home": the Lawyer As Civics Teacher in Everyday Practice

William & Mary Law Review Volume 50 (2008-2009) Issue 4 The Citizen Lawyer Symposium Article 5 3-1-2009 "Public Service Must Begin at Home": The Lawyer as Civics Teacher in Everyday Practice Bruce A. Green Russell G. Pearce Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr Part of the Legal Ethics and Professional Responsibility Commons, and the Legal Profession Commons Repository Citation Bruce A. Green and Russell G. Pearce, "Public Service Must Begin at Home": The Lawyer as Civics Teacher in Everyday Practice, 50 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 1207 (2009), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr/vol50/iss4/5 Copyright c 2009 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr "PUBLIC SERVICE MUST BEGIN AT HOME": THE LAWYER AS CIVICS TEACHER IN EVERYDAY PRACTICE BRUCE A. GREEN* & RUSSELL G. PEARCE** TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...................................... 1208 I. THE IDEA OF THE LAWYER AS Civics TEACHER ........... 1213 II. WHY LAWYERS SHOULD TEACH CIVICS WELL ........... 1219 A. Teaching Civics Well as a Public Service ............ 1220 B. Teaching Civics Well as Intrinsic to the Lawyer's Social Function ......................... 1223 1. The ABA /AALS Report's Idea of Lawyers' PedagogicRole as Derived from Their Social Function .......................... 1223 2. Antecedents to the ABA /AALS Report's Idea of Lawyers'PedagogicRole ........................ 1227 3. The Perpetuationof the ABA/AALS Report's Idea of Lawyers'PedagogicRole ................. 1231 III. THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE CONCEPT IN PROFESSIONAL AND ACADEMIC DISCOURSE ............. 1233 A. Serving the Public Good ......................... 1233 B. The Lawyer's Role in a Democracy ................ -

Five Ways to Write Like John Roberts by Ross Guberman

Five Ways to Write Like John Roberts By Ross Guberman hen Chief Justice John Roberts was a Or perhaps in A River Runs Through It . Watch how lawyer, he once wrote that determining Roberts explains the way the Red Dog Mine, the ac- W the “best” available technology for cused polluter in the case, got its name: controlling air pollution is like asking people to pick the “best” car: “Mario Andretti may select a Ferrari; a col- For generations, In- lege student a Volkswagen beetle; a family of six a mini- upiat Eskimos hunt- van. The choices would turn on how the decisionmaker ing and fishing in the weighed competing priorities such as cost, mileage, DeLong Mountains in safety, cargo space, speed, handling, and so on.” Northwest Alaska had been aware of orange- Did Roberts feel the same way about “best” when Ruth and red-stained Bader Ginsburg said that he was the “best” advocate to creekbeds in which come before the Supreme Court? Or when Senator fish could not survive. Chuck Schumer, who voted against his nomination, In the 1960s, a bush conceded that even Roberts’s opponents called him pilot and part-time “one of the best advocates, if not the best advocate, in prospector by the the nation”? name of Bob Baker noticed striking discolorations in the hills and creekbeds of a wide Unlike sports, advocacy writing may not evoke a hit list valley in the western DeLongs. Unable to land his of heroes. Even so, no one questions Roberts’s rock-star plane on the rocky tundra to investigate, Baker status as a briefwriter.