Facial Onset Sensory and Motor Neuronopathy New Cases, Cognitive Changes, and Pathophysiology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dystonia and Chorea in Acquired Systemic Disorders

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.65.4.436 on 1 October 1998. Downloaded from 436 J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1998;65:436–445 NEUROLOGY AND MEDICINE Dystonia and chorea in acquired systemic disorders Jina L Janavs, Michael J AminoV Dystonia and chorea are uncommon abnormal Associated neurotransmitter abnormalities in- movements which can be seen in a wide array clude deficient striatal GABA-ergic function of disorders. One quarter of dystonias and and striatal cholinergic interneuron activity, essentially all choreas are symptomatic or and dopaminergic hyperactivity in the nigros- secondary, the underlying cause being an iden- triatal pathway. Dystonia has been correlated tifiable neurodegenerative disorder, hereditary with lesions of the contralateral putamen, metabolic defect, or acquired systemic medical external globus pallidus, posterior and poste- disorder. Dystonia and chorea associated with rior lateral thalamus, red nucleus, or subtha- neurodegenerative or heritable metabolic dis- lamic nucleus, or a combination of these struc- orders have been reviewed frequently.1 Here we tures. The result is decreased activity in the review the underlying pathogenesis of chorea pathways from the medial pallidus to the and dystonia in acquired general medical ventral anterior and ventrolateral thalamus, disorders (table 1), and discuss diagnostic and and from the substantia nigra reticulata to the therapeutic approaches. The most common brainstem, culminating in cortical disinhibi- aetiologies are hypoxia-ischaemia and tion. Altered sensory input from the periphery 2–4 may also produce cortical motor overactivity medications. Infections and autoimmune 8 and metabolic disorders are less frequent and dystonia in some cases. To date, the causes. Not uncommonly, a given systemic dis- changes found in striatal neurotransmitter order may induce more than one type of dyski- concentrations in dystonia include an increase nesia by more than one mechanism. -

Post Stroke Focal Aware Seizures Presenting As Delayed Onset Choreoathetosis

Lehigh Valley Health Network LVHN Scholarly Works Department of Medicine Post Stroke Focal Aware Seizures Presenting as Delayed Onset Choreoathetosis Artish Patel USF MCOM - LVHN Campus, [email protected] Patrick Davis USF MCOM - LVHN Campus, [email protected] Beth Stepanczuk MD Lehigh Valley Health Network, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlyworks.lvhn.org/medicine Part of the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons Published In/Presented At Patel, A., Davis, P., & Stepanczuk, B. (2021, February 9-13). Post Stroke Focal Aware Seizures Presenting as Delayed Onset Choreoathetosis. [Poster presentation]. Association of Academic Physiatrists Annual Meeting, Virtual. This Poster is brought to you for free and open access by LVHN Scholarly Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in LVHN Scholarly Works by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Post Stroke Focal Aware Seizures Presenting as Delayed Onset Choreoathetosis Artish Patel, MD, BS, Patrick Davis, MD, BS, and Beth Stepanczuk, MD Lehigh Valley Health Network; Allentown, Pa. Setting Case Description Discussion Outpatient follow-up office She initially presented with acute onset confusion, nausea, This patient offered a rare case of focal aware seizures vomiting, and aphasia. Imaging revealed acute left parietal presenting as delayed onset choreoathetosis of the right Patient temporal intraparenchymal hemorrhage with surrounding upper extremity secondary to acute left parietal temporal 39-year-old female with history of migraines and recent left parietal edema and restricted diffusion consistent with infarction intraparenchymal hemorrhage. It has been documented that temporal intraparenchymal hemorrhage presenting at three- secondary to superior sagittal sinus thrombosis. -

Paraneoplastic Neurological and Muscular Syndromes

Paraneoplastic neurological and muscular syndromes Short compendium Version 4.5, April 2016 By Finn E. Somnier, M.D., D.Sc. (Med.), copyright ® Department of Autoimmunology and Biomarkers, Statens Serum Institut, Copenhagen, Denmark 30/01/2016, Copyright, Finn E. Somnier, MD., D.S. (Med.) Table of contents PARANEOPLASTIC NEUROLOGICAL SYNDROMES .................................................... 4 DEFINITION, SPECIAL FEATURES, IMMUNE MECHANISMS ................................................................ 4 SHORT INTRODUCTION TO THE IMMUNE SYSTEM .................................................. 7 DIAGNOSTIC STRATEGY ..................................................................................................... 12 THERAPEUTIC CONSIDERATIONS .................................................................................. 18 SYNDROMES OF THE CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM ................................................ 22 MORVAN’S FIBRILLARY CHOREA ................................................................................................ 22 PARANEOPLASTIC CEREBELLAR DEGENERATION (PCD) ...................................................... 24 Anti-Hu syndrome .................................................................................................................. 25 Anti-Yo syndrome ................................................................................................................... 26 Anti-CV2 / CRMP5 syndrome ............................................................................................ -

EMERGENCY CARE AID for ALTERNATING HEMIPLEGIA of CHILDHOOD (AHC) PATIENTS a Reference Guide for Medical Professionals

EMERGENCY CARE AID FOR ALTERNATING HEMIPLEGIA OF CHILDHOOD (AHC) PATIENTS A Reference Guide for Medical Professionals AHC DEFINITION: (Handb Clin Neurol. 2013; 112:821-6) Alternating hemiplegia of childhood (AHC) is a very rare disease characterized by recurrent attacks of loss of muscular tone resulting in hypomobility of one side of the body. The etiology of the disease is due to ATP1A3 gene mutations in the majority of patients. AHC has an onset in the first few months of life. Hemiplegic episodes are often accompanied by other paroxysmal manifestations, such as lateral eyes and head deviation toward the hemiplegic side and a very peculiar monocular nystagmus. Movement disorders such as dystonia and abnormal movements are frequent. Cognitive delay of variable degree is a common feature. Epilepsy has been reported in 50% of the cases, but seizure onset is usually during the third or fourth year of life. Many drugs have been used in AHC with very few results. Flunarizine has the most supportive anecdotal evidence regarding efficacy. AHC RISK FACTORS: TREATMENT: (Neurol Genet. 2017 Apr; 3(2): e139) There is no specific treatment for AHC. There is no approved medication or device that alters the underlying deficit in the Na+/K+ pump (see Flunarizine next page). NEUROLOGICAL: (Neurology. 2019 Sep 24;93(13)) Epilepsy is present in over 50% of AHC patients. Epilepsy in AHC can be focal or generalized seizures. Dystonia is also a common feature that affects the majority of patients dealing with AHC. Patients with AHC can deteriorate either abruptly or gradually at the motor and intellectual function level, depending on the severity of their disease. -

Dem11. Leukodystrophies.Pdf

LEUKODYSTROPHIES Dem11 (1) Leukodystrophies Last updated: September 5, 2017 ADRENOLEUKODYSTROPHY .................................................................................................................... 2 METACHROMATIC LEUKODYSTROPHIES (S. SULFATIDE LIPIDOSES) ..................................................... 3 GLOBOID CELL LEUKODYSTROPHY (S. KRABBE DISEASE) .................................................................... 4 PELIZAEUS-MERZBACHER DISEASE ........................................................................................................ 4 CANAVAN DISEASE (S. SPONGY DEGENERATION OF NERVOUS SYSTEM)................................................ 5 COCKAYNE SYNDROME............................................................................................................................ 5 ALEXANDER DISEASE ............................................................................................................................... 5 LEUKODYSTROPHIES - uncommon genetic biochemical defects of: a) myelin formation (synthesis) → DYSMYELINATION (→ loss of defective myelin); abnormal lipids incorporated into defective myelin are metachromatic. b) myelin maintenance (turnover) → DEMYELINATION (e.g. many sudanophilic leukodystrophies). N.B. sudanophilia is produced when Sudan black reacts with neutral fat breakdown products of myelin; since myelin breakdown is result of variety of metabolic or acquired insults, sudanophilia provides no useful information about pathogenesis! it is very difficult to distinguish -

Abnormal Movements in Critical Care Patients with Brain Injury: a Diagnostic Approach

Abnormal movements in critical care patients with brain injury: a diagnostic approach The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Hannawi, Yousef, Michael S. Abers, Romergryko G. Geocadin, and Marek A. Mirski. 2016. “Abnormal movements in critical care patients with brain injury: a diagnostic approach.” Critical Care 20 (1): 60. doi:10.1186/s13054-016-1236-2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/ s13054-016-1236-2. Published Version doi:10.1186/s13054-016-1236-2 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:26318575 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Hannawi et al. Critical Care (2016) 20:60 DOI 10.1186/s13054-016-1236-2 REVIEW Open Access Abnormal movements in critical care patients with brain injury: a diagnostic approach Yousef Hannawi1,2,3*, Michael S. Abers4, Romergryko G. Geocadin1,2,5 and Marek A. Mirski1,2,5 Abstract Abnormal movements are frequently encountered in patients with brain injury hospitalized in intensive care units (ICUs), yet characterization of these movements and their underlying pathophysiology is difficult due to the comatose or uncooperative state of the patient. In addition, the available diagnostic approaches are largely derived from outpatients with neurodegenerative or developmental disorders frequently encountered in the outpatient setting, thereby limiting the applicability to inpatients with acute brain injuries. -

Movement Disorders and Neurodegenerative Diseases

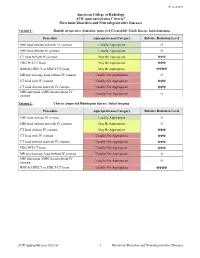

Revised 2019 American College of Radiology ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Movement Disorders and Neurodegenerative Diseases Variant 1: Rapidly progressive dementia; suspected Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Initial imaging. Procedure Appropriateness Category Relative Radiation Level MRI head without and with IV contrast Usually Appropriate O MRI head without IV contrast Usually Appropriate O CT head without IV contrast May Be Appropriate ☢☢☢ FDG-PET/CT brain May Be Appropriate ☢☢☢ HMPAO SPECT or SPECT/CT brain May Be Appropriate ☢☢☢☢ MR spectroscopy head without IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate O CT head with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢ CT head without and with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢ MRI functional (fMRI) head without IV Usually Not Appropriate O contrast Variant 2: Chorea; suspected Huntington disease. Initial imaging. Procedure Appropriateness Category Relative Radiation Level MRI head without IV contrast Usually Appropriate O MRI head without and with IV contrast May Be Appropriate O CT head without IV contrast May Be Appropriate ☢☢☢ CT head with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢ CT head without and with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢ FDG-PET/CT brain Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢ MR spectroscopy head without IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate O MRI functional (fMRI) head without IV Usually Not Appropriate O contrast HMPAO SPECT or SPECT/CT brain Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢☢ ACR Appropriateness Criteria® 1 Movement Disorders and Neurodegenerative Diseases Variant 3: Parkinsonian syndromes. Initial -

Disorders of Sphingolipid Synthesis, Sphingolipidoses, Niemann-Pick Disease Type C and Neuronal Ceroid Lipofuscinoses

551 38 Disorders of Sphingolipid Synthesis, Sphingolipidoses, Niemann-Pick Disease Type C and Neuronal Ceroid Lipofuscinoses Marie T. Vanier, Catherine Caillaud, Thierry Levade 38.1 Disorders of Sphingolipid Synthesis – 553 38.2 Sphingolipidoses – 556 38.3 Niemann-Pick Disease Type C – 566 38.4 Neuronal Ceroid Lipofuscinoses – 568 References – 571 J.-M. Saudubray et al. (Eds.), Inborn Metabolic Diseases, DOI 10.1007/978-3-662-49771-5_ 38 , © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2016 552 Chapter 38 · Disor ders of Sphingolipid Synthesis, Sphingolipidoses, Niemann-Pick Disease Type C and Neuronal Ceroid Lipofuscinoses O C 22:0 (Fatty acid) Ganglio- series a series b HN OH Sphingosine (Sphingoid base) OH βββ β βββ β Typical Ceramide (Cer) -Cer -Cer GD1a GT1b Glc ββββ βββ β Gal -Cer -Cer Globo-series GalNAc GM1a GD1b Neu5Ac βαββ -Cer Gb4 ββ β ββ β -Cer -Cer αβ β -Cer GM2 GD2 Sphingomyelin Pcholine-Cer Gb3 B4GALNT1 [SPG46] [SPG26] β β β ββ ββ CERS1-6 GBA2 -Cer -Cer ST3GAL5 -Cer -Cer So1P So Cer GM3 GD3 GlcCer - LacCer UDP-Glc UDP Gal CMP -Neu5Ac - UDP Gal PAPS Glycosphingolipids GalCer Sulfatide ββ Dihydro -Cer -Cer SO 4 Golgi Ceramide apparatus 2-OH- 2-OH-FA Acyl-CoA FA2H CERS1-6 [SPG35] CYP4F22 ω-OH- ω-OH- FA Acyl-CoA ULCFA ULCFA-CoA ULCFA GM1, GM2, GM3: monosialo- Sphinganine gangliosides Endoplasmic GD3, GD2, GD1a, GD1b: disialo-gangliosides reticulum KetoSphinganine GT1b: trisialoganglioside SPTLC1/2 [HSAN1] N-acetyl-neuraminic acid: sialic acid found in normal human cells Palmitoyl-CoA Deoxy-sphinganine + Serine +Ala or Gly Deoxymethylsphinganine 38 . Fig. 38.1 Schematic representation of the structure of the main sphingolipids , and their biosynthetic pathways. -

Chorea and Related Disorders R Bhidayasiri, D D Truong

527 Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pgmj.2004.019356 on 8 September 2004. Downloaded from REVIEW Chorea and related disorders R Bhidayasiri, D D Truong ............................................................................................................................... Postgrad Med J 2004;80:527–534. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2004.019356 Chorea refers to irregular, flowing, non-stereotyped, Other inherited causes are also discussed in more detail later in this review. In secondary chorea, random, involuntary movements that often possess a tardive syndromes are the most common causes, writhing quality referred to as choreoathetosis. When mild, related to long term use of dopamine blocking chorea can be difficult to differentiate from restlessness. agents. Choreiform movements can also result from structural brain lesions, mainly in the When chorea is proximal and of large amplitude, it is striatum, although most cases of secondary called ballism. Chorea is usually worsened by anxiety and chorea do not demonstrate any specific struc- stress and subsides during sleep. Most patients attempt to tural lesions. disguise chorea by incorporating it into a purposeful HEREDITARY CAUSES OF CHOREA activity. Whereas ballism is most often encountered as Huntington’s disease hemiballism due to contralateral structural lesions of the Huntington’s disease, the most common cause of chorea, is an autosomal dominant disorder subthalamic nucleus and/or its afferent or efferent caused by an expansion of an unstable trinucleo- projections, chorea may be the expression of a wide range tide repeat near the telomere of chromosome 4.12 of disorders, including metabolic, infectious, inflammatory, Each offspring of an affected family member has a 50% chance of having inherited the fully vascular, and neurodegenerative, as well as drug induced penetrant mutation. -

Clinical and Genetic Overview of Paroxysmal Movement Disorders and Episodic Ataxias

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Clinical and Genetic Overview of Paroxysmal Movement Disorders and Episodic Ataxias Giacomo Garone 1,2 , Alessandro Capuano 2 , Lorena Travaglini 3,4 , Federica Graziola 2,5 , Fabrizia Stregapede 4,6, Ginevra Zanni 3,4, Federico Vigevano 7, Enrico Bertini 3,4 and Francesco Nicita 3,4,* 1 University Hospital Pediatric Department, IRCCS Bambino Gesù Children’s Hospital, University of Rome Tor Vergata, 00165 Rome, Italy; [email protected] 2 Movement Disorders Clinic, Neurology Unit, Department of Neuroscience and Neurorehabilitation, IRCCS Bambino Gesù Children’s Hospital, 00146 Rome, Italy; [email protected] (A.C.); [email protected] (F.G.) 3 Unit of Neuromuscular and Neurodegenerative Diseases, Department of Neuroscience and Neurorehabilitation, IRCCS Bambino Gesù Children’s Hospital, 00146 Rome, Italy; [email protected] (L.T.); [email protected] (G.Z.); [email protected] (E.B.) 4 Laboratory of Molecular Medicine, IRCCS Bambino Gesù Children’s Hospital, 00146 Rome, Italy; [email protected] 5 Department of Neuroscience, University of Rome Tor Vergata, 00133 Rome, Italy 6 Department of Sciences, University of Roma Tre, 00146 Rome, Italy 7 Neurology Unit, Department of Neuroscience and Neurorehabilitation, IRCCS Bambino Gesù Children’s Hospital, 00165 Rome, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +0039-06-68592105 Received: 30 April 2020; Accepted: 13 May 2020; Published: 20 May 2020 Abstract: Paroxysmal movement disorders (PMDs) are rare neurological diseases typically manifesting with intermittent attacks of abnormal involuntary movements. Two main categories of PMDs are recognized based on the phenomenology: Paroxysmal dyskinesias (PxDs) are characterized by transient episodes hyperkinetic movement disorders, while attacks of cerebellar dysfunction are the hallmark of episodic ataxias (EAs). -

Dyskinesia Impairment Scale (DIS)

Dyskinesia Impairment Scale (DIS) The Dyskinesia Impairment Scale is developed to evaluate dystonia and choreoathetosis in dyskinetic cerebral palsy.1 The DIS consists of dystonia (DIS-D) and choreoathetosis (DIS-CA) subscales discriminating the presence and rating the severity (amplitude and duration) of either movement disorder in twelve body regions during activity and rest. Definitions: Definition Dyskinetic Cerebral Palsy (CP)2: Dyskinetic CP is characterized by involuntary, uncontrolled, recurring occasionally stereotyped movements, where the primitive reflex patterns predominate, and the muscle tone is varying. Two movement disorder patterns are dominantly present: dystonia and choreoathetosis Dystonia in CP refers to abnormal postures and/or involuntary or distorted voluntary twisting and repetitive movements due to sustained or intermittent muscle contractions. Choreoathetosis in CP is dominated by hyperkinesia and tone fluctuating (but mainly decreased). It can be differentiated in chorea, i.e. rapid involuntary, jerky and often fragmented movements, and athetosis, i.e. slower, constantly changing, writhing or contorting movements. Region descriptions in the Dyskinesia Impairment Scale: Re gio n DYSTONIA CHOREOATHETOSIS Eye Dystonia around the eyes, eyelids, eyebrow, forehe ad : e.g. sustained muscle Choreoathetosis around the eyes, eyelids, eyebrows, forehead : e.g. constantly, fragmented contractions (blepharospasms) around the eyes and/or the eyelid (open/closed) movements around the eyes and/or blinking eyelid (open/closed) and/or variable (saccadic) eye and/or forced eye movement deviations for example during eye tracking movements for example during eye tracking movement of fixation. movement of fixation. Mouth Dystonia around the lips, jaw, cheeks , tongue : e.g. sustained muscle Choreoathetosis lips, jaw, cheeks; tongue : e.g. -

Loss of the Sphingolipid Desaturase DEGS1 Causes Hypomyelinating Leukodystrophy

Loss of the sphingolipid desaturase DEGS1 causes hypomyelinating leukodystrophy Devesh C. Pant, … , Odile Boespflug-Tanguy, Aurora Pujol J Clin Invest. 2019;129(3):1240-1256. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI123959. Research Article Neuroscience Graphical abstract Find the latest version: https://jci.me/123959/pdf RESEARCH ARTICLE The Journal of Clinical Investigation Loss of the sphingolipid desaturase DEGS1 causes hypomyelinating leukodystrophy Devesh C. Pant,1,2 Imen Dorboz,3 Agatha Schluter,1,2 Stéphane Fourcade,1,2 Nathalie Launay,1,2 Javier Joya,1,2 Sergio Aguilera-Albesa,4 Maria Eugenia Yoldi,4 Carlos Casasnovas,1,2,5 Mary J. Willis,6 Montserrat Ruiz,1,2 Dorothée Ville,7 Gaetan Lesca,8 Karine Siquier-Pernet,9,10 Isabelle Desguerre,9,10 Huifang Yan,11,12 Jingmin Wang,11 Margit Burmeister,12,13 Lauren Brady,14 Mark Tarnopolsky,14 Carles Cornet,15 Davide Rubbini,15 Javier Terriente,15 Kiely N. James,16 Damir Musaev,16 Maha S. Zaki,17 Marc C. Patterson,18 Brendan C. Lanpher,19 Eric W. Klee,19,20 Filippo Pinto e Vairo,19,20 Elizabeth Wohler,21 Nara Lygia de M. Sobreira,22 Julie S. Cohen,23 Reza Maroofian,24 Hamid Galehdari,25 Neda Mazaheri,25,26 Gholamreza Shariati,26,27 Laurence Colleaux,9,10 Diana Rodriguez,28,29 Joseph G. Gleeson,16 Cristina Pujades,30 Ali Fatemi,23,31 Odile Boespflug-Tanguy,3,32 and Aurora Pujol1,2,33 1Neurometabolic Diseases Laboratory, Bellvitge Biomedical Research Institute (IDIBELL), 08908 L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain. 2Center for Biomedical Research on Rare Diseases (CIBERER), ISCIII, Madrid, Spain.