Mid–Century Lake Oswego

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE OREGONIAN!SATURDAY, MARCH 7, 2020 Homes&Gardens

C1!THE OREGONIAN!SATURDAY, MARCH 7, 2020 Homes&Gardens An easy-to-ignore 1962 dwelling has been restored and updated to take away distractions from the original clean lines. David Papazian Photography THE RE!REMODEL A midcentury modern home in Southwest Portland returns to architect John Storrs’ original vision Janet Eastman The Oregonian/OregonLive People can no longer knock on an unfitting front door that had been Eighteen years ago, a developer in Southwest Portland’s Lynnridge neigh- popped onto an admired architect’s Pacific Northwest modern dwelling. borhood sought to update the look of the midcentury modern by adding In its place: The dramatic double doors designed decades ago by John heavy layers of cherry wood and Craftsman-style doors and features. Storrs, a modernist renowned for his refined residential designs. Cherry wood was wrapped around a post in the living room and used as a The original doors, with glass and stained brown wood, once again set the built-in bu!et in the dining room as well as wide molding and a low-hanging stage for this 1962 custom house that the late, celebrated architect dressed in valance in the home office area o! the kitchen. natural Douglas fir, hemlock and other patinated and textured wood he saw as an “understandable, romantic material.” SEE RE!REMODEL, C4 GARDENING TODAY’S COLLECTIBLES Mild winter brings early roses, early diseases C2 Handmade objects from afar hold appeal. C6 67 C4 SATURDAYMARCH , 2020 7, THE OREGONIAN Returning to the midcentury modern style with warm finishes and sleek furnishings, spaces feel like “so much more,” says homeowner Abby Wool Landon. -

Pamplin Media Group - the Rise Central Is About to Rise in Downtown Beaverton

Pamplin Media Group - The Rise Central is about to rise in downtown Beaverton Friday, October 20, 2017 HOME NEWS OPINION FEATURES SPORTS OBITUARIES BUSINESS SHOP LOCAL CLASSIFIEDS ABOUT US FONT SHARE THIS MORE STORIES - A + < > The Rise Central is about to rise in downtown Beaverton Jules Rogers Thursday, October 12, 2017 DAILY NEWS WHERE YOU LIVE 0 Comments Beaverton Hillsboro Prineville Clackamas Lake Oswego Sandy Rembold Properties adds mixed-use Canby Madras Sellwood Columbia Co. Milwaukie Sherwood living to a downtown Beaverton group of Estacada Molalla Tigard developments. Forest Grove Newberg Tualatin Gladstone Oregon City West Linn Gresham Portland Wilsonville King City Portland SE Woodburn Happy Valley Portland SW SPECIAL INTEREST Biz Trib Wheels Public Notices Sustainable KPAM 860 Sunny 1550 Latest Comments Social Media Search SOURCE: CITY OF BEAVERTON, BY ANKROM MOISAN ARCHITECTS - A rendering of The Rise Central shows what it will look like when completed. Go to top http://portlandtribune.com/bvt/15-news/375144-255917-the-rise-central-is-about-to-rise-in-downtown-beaverton[10/20/2017 12:21:47 PM] Pamplin Media Group - The Rise Central is about to rise in downtown Beaverton Two new mixed-use buildings with all the fixings (dog and bike wash stations, retail, office, live-work units and bike storage a walkable distance from the MAX) are underway — in the suburbs. As part of the Beaverton Central development, a I Felt So compilation of projects located at the former Westgate Theater property and The Round, construction is Betrayed underway on two mixed-use buildings — called The Rise Central — which will include 230 residential units and 5,000 square feet of office space and retail space on the ground floor. -

Communications Law: Liberties, Restraints, and the Modern Media, Sixth Edition

Communications Law From the Wadsworth Series in Mass Communication and Journalism General Mass Communication Biagi, Media/Impact: An Introduction to Mass Media, Ninth Edition Hilmes, Connections: A Broadcast History Reader Hilmes, Only Connect: A Cultural History of Broadcasting in the United States, Third Edition Lester, Visual Communication: Images with Messages, Fifth Edition Overbeck, Major Principles of Media Law, 2011 Edition Straubhaar/LaRose, Media Now: Understanding Media, Culture, and Technology, Sixth Edition Zelezny, Cases in Communications Law, Sixth Edition Zelezny, Communications Law: Liberties, Restraints, and the Modern Media, Sixth Edition Journalism Bowles/Borden, Creative Editing, Sixth Edition Hilliard, Writing for Television, Radio, and New Media, Tenth Edition Kessler/McDonald, When Words Collide: A Media Writer’s Guide to Grammar and Style, Seventh Edition Rich, Writing and Reporting News: A Coaching Method, Sixth Edition Public Relations and Advertising Diggs-Brown, The PR Styleguide: Formats for Public Relations Practice, Second Edition Drewniany/Jewler, Creative Strategy in Advertising, Tenth Edition Hendrix, Public Relations Cases, Eighth Edition Newsom/Haynes, Public Relations Writing: Form and Style, Ninth Edition Newsom/Turk/Kruckeberg, This Is PR: The Realities of Public Relations, Tenth Edition Research and Theory Baran and Davis, Mass Communication Theory: Foundations, Ferment, and Future, Fifth Edition Sparks, Media Effects Research: A Basic Overview, Third Edition Wimmer/Dominick, Mass Media Research: An Introduction, Ninth Edition Communications Law Liberties, Restraints, and the Modern Media Sixth Edition John D. Zelezny Attorney at Law Australia • Brazil • Japan • Korea • Mexico • Singapore • Spain • United Kingdom • United States Communications Law: Liberties, Restraints, © 2011, 2006, 2004 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning and the Modern Media, Sixth Edition ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. -

Oregon Newspapers on Microfilm Alphabetical Listing by Town

Oregon Newspapers on Microfilm Alphabetical Listing by Town This inventory comprises the Research Library’s holdings of Oregon newspapers on microfilm, arranged alphabetically by town. Please note that due to irregular filming schedules, there may be gaps in some of the more recent publications. ALBANY (Linn) The Albany Democrat (D) May 7, 1888‐Mar 31, 1894; Aug 3, 1898‐Aug 9, 1907; Nov 13, 1914‐Mar 1, 1925 Cabinet A, Drawer 1 Albany Democrat (W) Apr. 27, 1900‐Jan. 31, 1913 Cabinet A, Drawer 1 Albany Democrat‐Herald Mar. 2, 1925‐March 5, 1947 Cabinet A, Drawer 1 March 6, 1947‐June 1969 Cabinet A, Drawer 2 July 1969‐March 20, 1978 Cabinet A, Drawer 3 - 1 - March 21, 1978‐Jan. 13, 1989 Cabinet A, Drawer 4 Jan. 14, 1989‐Oct. 20, 1998 Cabinet A, Drawer 5 Oct. 20, 1998‐present Cabinet BB, Drawer 1 Albany Evening Democrat Dec. 6, 1875‐Mar. 11, 1876 Cabinet A, Drawer 1 Albany Evening Herald Oct. 19, 1910‐Apr. 5, 1912; July 28, 1920‐Feb. 28, 1925 Cabinet A, Drawer 5 The Albany Inquirer Sept. 27, 1862 Oregon Newspapers Suppressed During Civil War, Reel 1 Cabinet CC, Drawer 2 Albany Weekly Herald Feb. 26, 1909‐Sept. 22, 1910 Cabinet A, Drawer 5 Daily Albany Democrat Mar. 14, 1876‐ June 3, 1876 Cabinet A, Drawer 1 (same reel as Albany Evening Democrat) The Oregon Democrat Nov. 1, 1859‐Jan. 22, 1861; 1862‐64 [scattered dates] Cabinet A, Drawer 6 July 17, 1860‐May 8, 1864 Oregon Papers Suppressed During Civil War, Reel 1 Cabinet CC, Drawer 2 Oregon Good Templar July 21, 1870‐ June 26, 1872 Cabinet A, Drawer 6 - 2 - Oregon Populist Jan. -

2019 Annual Directory 1 Our Readers Enjoy Many Oregon Newspaper Platform Options to Get Their Publishers Association Local News

2019 ANNUAL DIRECTORY 1 Our readers enjoy many OREGON NEWSPAPER platform options to get their PUBLISHERS ASSOCIATION local news. This year’s cover was designed by 2019 Sherry Alexis www.sterryenterprises.com ANNUAL DIRECTORY Oregon Newspaper Publishers Association Real Acces Media Placement Publisher: Laurie Hieb Oregon Newspapers Foundation 4000 Kruse Way Place, Bld 2, STE 160 Portland OR 97035 • 503-624-6397 Fax 503-639-9009 Email: [email protected] Web: www.orenews.com TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 2018 ONPA and ONF directors 4 Who to call at ONPA 4 ONPA past presidents and directors 5 About ONPA 6 Map of General Member newspapers 7 General Member newspapers by owner 8 ONPA General Member newspapers 8 Daily/Multi-Weekly 12 Weekly 24 Member newspapers by county 25 ONPA Associate Member publications 27 ONPA Collegiate Member newspapers 28 Regional and National Associations 29 Newspaper Association of Idaho 30 Daily/Multi-Weekly 30 Weekly 33 Washington Newspaper Publishers Assoc. 34 Daily/Multi-Weekly 34 Weekly Return TOC 2018-19 BOARDS OF DIRECTORS Oregon Newspaper Publishers Association PRESIDENT president-elect IMMEDIATE PAST DIRECTOR PRESIDENT Joe Petshow Lyndon Zaitz Scott Olson Hood River News Keizertimes Mike McInally The Creswell Corvallis Gazette Chronical Times DIRECTOR DIRECTOR DIRECTOR DIRECTOR John Maher Julianne H. Tim Smith Scott Swanson Newton The Oregonian, The News Review The New Era, Portland Ph.D., University of Sweet Home Oregon Roseburg DIRECTOR DIRECTOR DIRECTOR DIRECTOR Chelsea Marr Emily Mentzer Nikki DeBuse Jeff Precourt The Dalles Chronicle Itemizer-Observer The World, Coos Bay Forest Grove News / Gazette-Times, Dallas Times - Hillsboro Corvallis / Democrat- Tribune Herald, Albany Oregon Newspapers Foundation DIRECTOR DIRECTOR PRESIDENT TREASURER Mike McInally Therese Joe Petshow James R. -

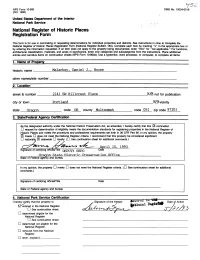

Malarkey, Daniel J., House Other Names/Site Number

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service , x . National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1 . Name of Property ~ historic name Malarkey, Daniel J., House other names/site number 2. Location street & number 2141 SW Hillcrest Place not for publication city or town Portland state Oregon code OR county Multnomah code 051 zip code 97201 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, 1 hereby certify that this B nomination D request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Pan" 60. In my opinion, the property ® meets D does not meet the National Register criteria. 1 recommend that this property be considered significant D nationally" 1X1 statewide D locally. -

Voters' Pamphlet

MULTNOMAH COUNTY VOTERS’ PAMPHLET GENERAL ELECTION - NOVEMBER 7, 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS CANDIDATES: CITY OF TROUTDALE Beaverton School District (34-139) M-41 MULTNOMAH COUNTY City Council, Position #1 M-12 David Douglas School District (26-85) M-42 Commissioner, District #2 M-3 City Council, Position #3 M-13 Hillsboro School District (34-128) M-45 CITY OF FAIRVIEW City Council, Position #5 M-14 Mt. Hood Community College (26-83) M-46 Mayor M-4 EAST MULTNOMAH SWCD Portland School District (26-84) M-51 City Council, Position #4 M-4 Director, Zone 2 & Zone 3 M-15 Reynolds School District (26-88) M-57 City Council, Position #5 M-5 Director, At Large M-16 West Multnomah SWCD (26-82) M-60 City Council, Position #6 M-5 WEST MULTNOMAH SWCD Lusted Water District (26-87) M-63 CITY OF GRESHAM Director, At Large M-16 Scappoose RFPD (5-153) M-64 Mayor M-6 ROCKWOOD PUD Tualatin Valley Fire & Rescue (34-133) M-66 City Council, Position #2 M-7 Director, Subdistrict #2 M-17 MISCELLANEOUS: City Council, Position #4 M-7 MEASURES: Voters’ Information Letter M-2 City Council, Position #6 M-8 Multnomah County (26-81) M-18 Commissioner District Map M-69 CITY OF LAKE OSWEGO Metro (26-80) M-24 Drop Site Locations M-70 City Council M-10 City of Portland (26-88) M-36 Library Drop Sites M-71 Making It Easy to Vote M-72 ATTENTION This is the beginning of your county voters’ pamphlet. The county portion of this voters’ pamphlet is inserted in the center of the state portion. -

0110-LO A1-4.Indd

Looking back Strong Before he died, John Peterson start shared his history in a letter Pacer boys — See A11 on a roll as league play approaches — See SPORTS, A21 THURSDAY, JANUARY 10, 2013 • ONLINE AT LAKEOSWEGOREVIEW.COM • VOLUME 100, NO. 2 • 75 CENTS LO offers Seventh annual Lake Oswego West Linn $5 million Reads program kicks off for pipeline route WL residents question timing Jessica Lee, a student at and amount of agreement Lake Oswego High School, By LORI HALL helped For the Review distribute copies of Lake Oswego made a $5 million offer to “Running the West Linn that could sweeten the pot in get- Rift” at the ting its water treatment plant project and kickoff event pipeline approved. Monday. On Monday, the West Linn City Council ap- Below, Lake proved pursuing an agreement with the Lake Owego-Tigard Water Partnership (LOT) for a $5 Oswego million lump-sum payment for the use of city teamaker right-of-way for a proposed water pipeline that is Steven Smith in conjunction with the proposed LOT water treat- brewed ment plant expansion. Rwandan tea However, at the fi rst session of the new Lake as a special Oswego City Council Tuesday evening, new May- treat for or Kent Studebaker said that neither the previous those in council or the current council had authorized this attendance. See OFFER / Page A3 REVIEW PHOTOS: VERN UYETAKE ■ Copies of ‘Running the Rift’ distributed Monday night he Lake Oswego Reads 2013 baskets and jewelry, courtesy of the Hutu-Tutsi confl ict in Rwanda. Despite New trolley program got off to a tremen- Itafari Foundation, founded by Lake Os- the troubles the characters experience, dous start Monday with the wego resident Victoria Trabosh. -

Inside Chromium 6 Emissions from ESCO

november 09 VOLUME 24, ISSUE 3 FREE Serving Portland’s Northwest Neighborhoods since 1986 Goodbye mikE ryErson free parking Singer to delay garage construction to get meters in place By allan Classen ayor Sam Adams and developer Richard Singer have a tenta- tive agreement to postpone construction of Singer’s Irving Street Garage until parking meters can be installed in the Northwest District. Adams expects authorizing and installing meters will take at least a year, delaying slightly Singer’s previously announced intention to begin work next summer. MCity Council affirmed last month that Singer has indisputable approval for the three-level garage, one of six prescribed by City Council in 2003 but put on hold by a series of appeals by the Northwest District Association. “I am pleased in my conversations with Dick Singer,” Adams said at an Oct. 21 council session, “that he has agreed to delay the demolition of the house and the construction of the garage … to give time to look at the full potential of an on-street parking plan, and I appreciate that goodwill gesture.” Adams’ aide, Amy Ruiz, said the agreement with Singer is not final. “We’re hoping to get to a place where he gets what he needs for a real Continued on page 7 Despite denials, DeQ knew of deadly inside chromium 6 emissions from eSCo By paul Koberstein problems. Thanks to Brockovich, they for it in mid-July. won a $333 million court settlement from In fact, DEQ has provided misleading, In the movie Erin Brockovich, a UCLA PG&E and brought a halt to the dumping. -

Juijag^'^OE/Ow Ws EH Determined Not Eligible for the National Register

NPS Form 10-900 0MB No. 10240018 (Rev. 8-86) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service fl National Register of Historic Places Registration Form NATJGNAI This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. See instructions m Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, styles, materials, and areas of significance, enter only the categories and subcategories listed in the instructions. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900a). Type all entries. 1. Name of Property_________________________________________________ historic name Chi Psi Fraternity other names/site number Chi Psi Lodge 2. Location street & number ima Hi 13fard Street N 4vl not for publication city, town raiq»ne Kf 4V vicinity State Oregon code county code zip code 3. Classification Ownership of Property Category of Property Number of Resources within Property fx"l private building(s) Contributing Noncontributing rn public-local g district 1 ____ buildings I I public-State EH site ____ ____ sites I I public-Federal I I structure ____ ____ structures I I object ____ ____ objects I 0 Total Name of related multiple property listing: Number of contributing resources previously Eugene West University Neighborhood Historic and listed in the National Register N/A al.RpcouroQc ate/Feoeral %AgencyA cation As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this I I nomination Exl request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

Silver Spoon Oligarchs

CO-AUTHORS Chuck Collins is director of the Program on Inequality and the Common Good at the Institute for Policy Studies where he coedits Inequality.org. He is author of the new book The Wealth Hoarders: How Billionaires Pay Millions to Hide Trillions. Joe Fitzgerald is a research associate with the IPS Program on Inequality and the Common Good. Helen Flannery is director of research for the IPS Charity Reform Initiative, a project of the IPS Program on Inequality. She is co-author of a number of IPS reports including Gilded Giving 2020. Omar Ocampo is researcher at the IPS Program on Inequality and the Common Good and co-author of a number of reports, including Billionaire Bonanza 2020. Sophia Paslaski is a researcher and communications specialist at the IPS Program on Inequality and the Common Good. Kalena Thomhave is a researcher with the Program on Inequality and the Common Good at the Institute for Policy Studies. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors wish to thank Sarah Gertler for her cover design and graphics. Thanks to the Forbes Wealth Research Team, led by Kerry Dolan, for their foundational wealth research. And thanks to Jason Cluggish for using his programming skills to help us retrieve private foundation tax data from the IRS. THE INSTITUTE FOR POLICY STUDIES The Institute for Policy Studies (www.ips-dc.org) is a multi-issue research center that has been conducting path-breaking research on inequality for more than 20 years. The IPS Program on Inequality and the Common Good was founded in 2006 to draw attention to the growing dangers of concentrated wealth and power, and to advocate policies and practices to reverse extreme inequalities in income, wealth, and opportunity. -

Portland Historic Landmarks Commission

State of the City Preservation Report 2017 PORTLAND HISTORIC LANDMARKS COMMISSION November 2017 Cover Images - Housing in Historic Contexts: Portland’s historic resources and historic districts offer a diverse array of housing types, including a range of affordable housing options, that also support the unique character of our neighborhoods. The cover images (identified from top left to bottom right) illustrate this diversity and are located throughout the city. 1. 1923 APARTMENT BUILDING - IRVINGTON HISTORIC DISTRICT 2. ERICKSON-FRITZ APARTMENTS (REPURPOSED SALOON + HOTEL) - SKIDMORE/OLD TOWN HISTORIC DISTRICT 3. SINGLE FAMILY CONVERSION TO 6-UNITS - ALPHABET HISTORIC DISTRICT 4. DUPLEX - IRVINGTON HISTORIC DISTRICT 5. CARRIE BLAKEY HOUSE TRIPLEX - BUCKMAN NEIGHBORHOOD 6. MIXED USE COMMERCIAL/RESIDENTIAL NEW DEVELOPMENT - ALPHABET HISTORIC DISTRICT 7. ACCESSORY DWELLING UNIT - IRVINGTON HISTORIC DISTRICT (source: https://accessorydwellings.org/2016/10/21/nielson-pitt-mix-adu/) 8. 1929 TESHNOR MANOR - ALPHABET HISTORIC DISTRICT 9. ACCESSORY DWELLING UNIT - LADD’S ADDITION HISTORIC DISTRICT (source: https://smallhousebliss.com/2014/09/13/jack-barnes-architect-pdx-eco-cottage/) STATE OF THE CITY PRESERVATION REPORT 2017 | PORTLAND HISTORIC LANDMARKS COMMISSION Report Contents Current Commission 1 Letter from the Chair 2 2018 Priorities & Goals 3 Current Preservation Issues 5 2016-17 Accomplishments 15 Historic Resource Watchlist 17 Portland Historic Landmarks Commission The Portland Historic Landmarks Commission PROVIDES LEADERSHIP AND EXPERTISE ON MAINTAINING AND ENHANCING PORTLAND’S ARCHITECTURAL AND CULTURAL HERITAGE. The Commission reviews development proposals for alterations to historic buildings and new construction in historic districts. The Commission also provides advice on historic preservation matters and coordinates historic preservation programs in the City. Current Commission Members KIRK RANZETTA, CHAIR – Commissioner Ranzetta is a CARIN CARLSON – Commissioner Carlson is a licensed PhD architectural historian.