RNA Editing of Human Micrornas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

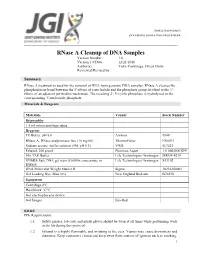

Rnase a Cleanup of DNA Samples Version Number: 1.0 Version 1.0 Date: 12/21/2016 Author(S): Yuko Yoshinaga, Eileen Dalin Reviewed/Revised By

SAMPLE MANAGEMENT STANDARD OPERATING PROCEDURE RNase A Cleanup of DNA Samples Version Number: 1.0 Version 1.0 Date: 12/21/2016 Author(s): Yuko Yoshinaga, Eileen Dalin Reviewed/Revised by: Summary RNase A treatment is used for the removal of RNA from genomic DNA samples. RNase A cleaves the phosphodiester bond between the 5'-ribose of a nucleotide and the phosphate group attached to the 3'- ribose of an adjacent pyrimidine nucleotide. The resulting 2', 3'-cyclic phosphate is hydrolyzed to the corresponding 3'-nucleoside phosphate. Materials & Reagents Materials Vendor Stock Number Disposables 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tubes Reagents TE Buffer, pH 8.0 Ambion 9849 RNase A, DNase and protease-free (10 mg/ml) ThermoFisher EN0531 Sodium acetate buffer solution (3M, pH 5.2) VWR 567422 Ethanol, 200 proof Pharmco-Aaper 111000200CSPP 50x TAE Buffer Life Technologies/ Invitrogen MRGF-4210 SYBR® Safe DNA gel stain (10,000x concentrate in Life Technologies/ Invitrogen S33102 DMSO) DNA Molecular Weight Marker II Sigma 10236250001 Gel Loading Dye, Blue (6x) New England BioLabs B7021S Equipment Centrifuge 4°C Heat block 37°C Gel electrophoresis device Gel Imager Bio-Rad EH&S PPE Requirements: 1.1 Safety glasses, lab coat, and nitrile gloves should be worn at all times while performing work in the lab during this protocol. 1.2 Ethanol is a highly flammable and irritating to the eyes. Vapors may cause drowsiness and dizziness. Keep containers closed and keep away from sources of ignition such as smoking. 1 SAMPLE MANAGEMENT STANDARD OPERATING PROCEDURE Avoid contact with skin and eyes. In case of contact with eyes, rinse immediately with plenty of water and seek medical advice. -

Distinct E-Cadherin-Based Complexes Regulate Cell Behaviour Through Mirna Processing Or Src and P120 Catenin Activity

ARTICLES Distinct E-cadherin-based complexes regulate cell behaviour through miRNA processing or Src and p120 catenin activity Antonis Kourtidis1, Siu P. Ngok1,5, Pamela Pulimeno2,5, Ryan W. Feathers1, Lomeli R. Carpio1, Tiffany R. Baker1, Jennifer M. Carr1, Irene K. Yan1, Sahra Borges1, Edith A. Perez3, Peter Storz1, John A. Copland1, Tushar Patel1, E. Aubrey Thompson1, Sandra Citi4 and Panos Z. Anastasiadis1,6 E-cadherin and p120 catenin (p120) are essential for epithelial homeostasis, but can also exert pro-tumorigenic activities. Here, we resolve this apparent paradox by identifying two spatially and functionally distinct junctional complexes in non-transformed polarized epithelial cells: one growth suppressing at the apical zonula adherens (ZA), defined by the p120 partner PLEKHA7 and a non-nuclear subset of the core microprocessor components DROSHA and DGCR8, and one growth promoting at basolateral areas of cell–cell contact containing tyrosine-phosphorylated p120 and active Src. Recruitment of DROSHA and DGCR8 to the ZA is PLEKHA7 dependent. The PLEKHA7–microprocessor complex co-precipitates with primary microRNAs (pri-miRNAs) and possesses pri-miRNA processing activity. PLEKHA7 regulates the levels of select miRNAs, in particular processing of miR-30b, to suppress expression of cell transforming markers promoted by the basolateral complex, including SNAI1, MYC and CCND1. Our work identifies a mechanism through which adhesion complexes regulate cellular behaviour and reveals their surprising association with the microprocessor. p120 catenin (p120) was identified as a tyrosine phosphorylation with this, E-cadherin is still expressed in several types of aggressive substrate of the Src oncogene1 and an essential component of the and metastatic cancer18–20. -

Secretariat of the CBD Technical Series No. 82 Convention on Biological Diversity

Secretariat of the CBD Technical Series No. 82 Convention on Biological Diversity 82 SYNTHETIC BIOLOGY FOREWORD To be added by SCBD at a later stage. 1 BACKGROUND 2 In decision X/13, the Conference of the Parties invited Parties, other Governments and relevant 3 organizations to submit information on, inter alia, synthetic biology for consideration by the Subsidiary 4 Body on Scientific, Technical and Technological Advice (SBSTTA), in accordance with the procedures 5 outlined in decision IX/29, while applying the precautionary approach to the field release of synthetic 6 life, cell or genome into the environment. 7 Following the consideration of information on synthetic biology during the sixteenth meeting of the 8 SBSTTA, the Conference of the Parties, in decision XI/11, noting the need to consider the potential 9 positive and negative impacts of components, organisms and products resulting from synthetic biology 10 techniques on the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity, requested the Executive Secretary 11 to invite the submission of additional relevant information on this matter in a compiled and synthesised 12 manner. The Secretariat was also requested to consider possible gaps and overlaps with the applicable 13 provisions of the Convention, its Protocols and other relevant agreements. A synthesis of this 14 information was thus prepared, peer-reviewed and subsequently considered by the eighteenth meeting 15 of the SBSTTA. The documents were then further revised on the basis of comments from the SBSTTA 16 and peer review process, and submitted for consideration by the twelfth meeting of the Conference of 17 the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity. -

U6 Small Nuclear RNA Is Transcribed by RNA Polymerase III (Cloned Human U6 Gene/"TATA Box"/Intragenic Promoter/A-Amanitin/La Antigen) GARY R

Proc. Nati. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 83, pp. 8575-8579, November 1986 Biochemistry U6 small nuclear RNA is transcribed by RNA polymerase III (cloned human U6 gene/"TATA box"/intragenic promoter/a-amanitin/La antigen) GARY R. KUNKEL*, ROBIN L. MASERt, JAMES P. CALVETt, AND THORU PEDERSON* *Cell Biology Group, Worcester Foundation for Experimental Biology, Shrewsbury, MA 01545; and tDepartment of Biochemistry, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS 66103 Communicated by Aaron J. Shatkin, August 7, 1986 ABSTRACT A DNA fragment homologous to U6 small 4A (20) was screened with a '251-labeled U6 RNA probe (21, nuclear RNA was isolated from a human genomic library and 22) using a modified in situ plaque hybridization protocol sequenced. The immediate 5'-flanking region of the U6 DNA (23). One of several positive clones was plaque-purified and clone had significant homology with a potential mouse U6 gene, subsequently shown by restriction mapping to contain a including a "TATA box" at a position 26-29 nucleotides 12-kilobase-pair (kbp) insert. A 3.7-kbp EcoRI fragment upstream from the transcription start site. Although this containing U6-hybridizing sequences was subcloned into sequence element is characteristic of RNA polymerase II pBR322 for further restriction mapping. An 800-base-pair promoters, the U6 gene also contained a polymerase III "box (bp) DNA fragment containing U6 homologous sequences A" intragenic control region and a typical run of five thymines was excised using Ava I and inserted into the Sma I site of at the 3' terminus (noncoding strand). The human U6 DNA M13mp8 replicative form DNA (M13/U6) (24). -

Expanding the Genetic Code Lei Wang and Peter G

Reviews P. G. Schultz and L. Wang Protein Science Expanding the Genetic Code Lei Wang and Peter G. Schultz* Keywords: amino acids · genetic code · protein chemistry Angewandte Chemie 34 2005 Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim DOI: 10.1002/anie.200460627 Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44,34–66 Angewandte Protein Science Chemie Although chemists can synthesize virtually any small organic molecule, our From the Contents ability to rationally manipulate the structures of proteins is quite limited, despite their involvement in virtually every life process. For most proteins, 1. Introduction 35 modifications are largely restricted to substitutions among the common 20 2. Chemical Approaches 35 amino acids. Herein we describe recent advances that make it possible to add new building blocks to the genetic codes of both prokaryotic and 3. In Vitro Biosynthetic eukaryotic organisms. Over 30 novel amino acids have been genetically Approaches to Protein encoded in response to unique triplet and quadruplet codons including Mutagenesis 39 fluorescent, photoreactive, and redox-active amino acids, glycosylated 4. In Vivo Protein amino acids, and amino acids with keto, azido, acetylenic, and heavy-atom- Mutagenesis 43 containing side chains. By removing the limitations imposed by the existing 20 amino acid code, it should be possible to generate proteins and perhaps 5. An Expanded Code 46 entire organisms with new or enhanced properties. 6. Outlook 61 1. Introduction The genetic codes of all known organisms specify the same functional roles to amino acid residues in proteins. Selectivity 20 amino acid building blocks. These building blocks contain a depends on the number and reactivity (dependent on both limited number of functional groups including carboxylic steric and electronic factors) of a particular amino acid side acids and amides, a thiol and thiol ether, alcohols, basic chain. -

"Modified" RNA (And DNA) World

July editorial The "modified" RNA (and DNA) world A few months ago, as COVID-19 vaccinations were getting underway in the U.S., a non-scientist friend said he was uneasy because had heard that the RNA in them had been "doped". Leaning in, I asked "How?" (I knew of course, vide infra). "With some chemical" he replied. This struck me as a perfect storm of an educated, reasonably informed non- scientist being led astray by how the media often doesn't get it quite right, though we all recognize that too much detail can be narcoleptic. The art is to convey the science in just the right dose, as Lewis Thomas and Carl Sagan did for example (1). I told my friend what the "doping" was, using lay terms. He listened thoughtfully and then I came in with my final shot: nature is full of RNA that is "doped", and even DNA is as well. These chemical modifications are not done by mad scientists but the very biological systems in which these RNAs and DNAs reside, using their own enzymes. He left somewhat convinced and hopefully is now vaccinated. This encounter gave me the thought that I, and my readers, should take a step back and think about all the "modified" RNAs and DNAs out there. For transfer RNAs alone, there are 120 known base modifications, with their prevalence as high as 13 of the 76 nucleotides in human cytosolic tRNAtyr(2). N6- adenosine methylation of messenger RNA, discovered in 1974, has recently come to the fore, although not all experts agree on its functional significance (3,4). -

Chapter 3. the Beginnings of Genomic Biology – Molecular

Chapter 3. The Beginnings of Genomic Biology – Molecular Genetics Contents 3. The beginnings of Genomic Biology – molecular genetics 3.1. DNA is the Genetic Material 3.6.5. Translation initiation, elongation, and termnation 3.2. Watson & Crick – The structure of DNA 3.6.6. Protein Sorting in Eukaryotes 3.3. Chromosome structure 3.7. Regulation of Eukaryotic Gene Expression 3.3.1. Prokaryotic chromosome structure 3.7.1. Transcriptional Control 3.3.2. Eukaryotic chromosome structure 3.7.2. Pre-mRNA Processing Control 3.3.3. Heterochromatin & Euchromatin 3.4. DNA Replication 3.7.3. mRNA Transport from the Nucleus 3.4.1. DNA replication is semiconservative 3.7.4. Translational Control 3.4.2. DNA polymerases 3.7.5. Protein Processing Control 3.4.3. Initiation of replication 3.7.6. Degradation of mRNA Control 3.4.4. DNA replication is semidiscontinuous 3.7.7. Protein Degradation Control 3.4.5. DNA replication in Eukaryotes. 3.8. Signaling and Signal Transduction 3.4.6. Replicating ends of chromosomes 3.8.1. Types of Cellular Signals 3.5. Transcription 3.8.2. Signal Recognition – Sensing the Environment 3.5.1. Cellular RNAs are transcribed from DNA 3.8.3. Signal transduction – Responding to the Environment 3.5.2. RNA polymerases catalyze transcription 3.5.3. Transcription in Prokaryotes 3.5.4. Transcription in Prokaryotes - Polycistronic mRNAs are produced from operons 3.5.5. Beyond Operons – Modification of expression in Prokaryotes 3.5.6. Transcriptions in Eukaryotes 3.5.7. Processing primary transcripts into mature mRNA 3.6. Translation 3.6.1. -

The Oncogenic Role of Mir-155 in Breast Cancer

Published OnlineFirst June 26, 2012; DOI: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0173 Cancer Epidemiology, MiniReview Biomarkers & Prevention The Oncogenic Role of miR-155 in Breast Cancer Sam Mattiske, Rachel J. Suetani, Paul M. Neilsen, and David F. Callen Abstract miR-155isanoncogenicmiRNAwithwelldescribedrolesinleukemia.However,additionalrolesof miR-155 in breast cancer progression have recently been described. A thorough literature search was conducted to review all published data to date, examining the role of miR-155 in breast cancer. Data on all validated miR-155 target genes was collated to identify biologic pathways relevant to miR-155 and breast cancer progression. Publications describing the clinical relevance, functional characterization, and regu- lation of expression of miR-155 in the context of breast cancer are reviewed. A total of 147 validated miR- 155 target genes were identified from the literature. Pathway analysis of these genes identified likely roles in apoptosis, differentiation, angiogenesis, proliferation, and epithelial–mesenchymal transition. The large number of validated miR-155 targets presented here provide many avenues of interest as to the clinical potential of miR-155. Further investigation of these target genes will be required to elucidate the specific mechanisms and functions of miR-155 in breast cancer. This is the first review examining the role of miR- 155 in breast cancer progression. The collated data of target genes and biologic pathways of miR-155 identified in this review suggest new avenues of research for this oncogenic miRNA. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev; 21(8); 1236–43. Ó2012 AACR. Introduction found to regulate levels of LIN-14 protein (7, 8). Since this miRNAs are small noncoding RNAs that control discovery, there have been over 500 miRNAs described, expression of target genes by either inhibiting protein regulating a wide range of genes and cellular processes, translation or directly targeting mRNA transcripts of although the total predicted number of unique miRNAs target genes for degradation (1). -

Evaluation of the Quality, Safety and Efficacy of Messenger RNA

1 2 3 WHO/BS/2021.2402 4 ENGLISH ONLY 5 6 7 8 9 Evaluation of the quality, safety and efficacy of messenger RNA vaccines for 10 the prevention of infectious diseases: regulatory considerations 11 12 13 14 15 16 NOTE: 17 18 This draft document has been prepared for the purpose of inviting comments and suggestions on 19 the proposals contained therein which will then be considered by the WHO Expert Committee on 20 Biological Standardization (ECBS). The distribution of this draft document is intended to 21 provide information on the proposed document: Evaluation of the quality, safety and efficacy of 22 messenger RNA vaccines for the prevention of infectious diseases: regulatory considerations to a 23 broad audience and to ensure the transparency of the consultation process. 24 25 The text in its present form does not necessarily represent the agreed formulation of the 26 ECBS. Written comments proposing modifications to this text MUST be received by 17 27 September 2021 using the Comment Form available separately and should be addressed to 28 the Department of Health Products Policy and Standards, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue 29 Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland. Comments may also be submitted electronically to the 30 Responsible Officer: Dr Tiequn Zhou at: [email protected]. 31 32 The outcome of the deliberations of the Expert Committee will be published in the WHO 33 Technical Report Series. The final agreed formulation of the document will be edited to be in 34 conformity with the second edition of the WHO style guide (KMS/WHP/13.1). -

TOTAL RNA Microrna LABELED CRNA GENOMIC DNA HYB MIX

YALE CENTER FOR GENOME ANALYSIS – MICROARRAY SAMPLE SUBMISSION FORM SHIP TO: YCGA B‐36, 300 HEFFERNAN DRIVE, WEST HAVEN, CT 06516; 203‐737‐3047 (LAB); 203‐737‐3104 (FAX) NAME DATE NEW USER? YES NO‐ YMD USER CODE: E‐MAIL ADDRESS (ONE ONLY) TO SEND DATA P.I. BILLING ADDRESS P.I. E‐MAIL ADDRESS DEPARTMENT INSTITUTION SHIPPING ADDRESS TELEPHONE # YALE PTAEO / PURCHASE ORDER # SPLIT CHARGING? 2ND PTAEO SAMPLE TYPE SERVICE REQUESTED PLATFORM TOTAL RNA FULL SERVICE GENE EXPRESSION PROFILING* AFFYMETRIX (ISOLATED & PURIFIED) NUGEN GENE EXPRESSION PROFILING* microRNA FULL SERVICE SNP GENOTYPING* EXIQON (ISOLATED & PURIFIED) METHLYATION* LABELED CRNA ILLUMINA (PURIFIED) MICRORNA EXPRESSION PROFILING GENOMIC DNA HYBRIDIZATION ONLY NIMBLEGEN (ISOLATED & PURIFIED) SAMPLE QC (SPECTROPHOTOMETRY & BIOANALYZER) HYB MIX OTHER: SEQUENOM CELL TYPE / EXTRACTION METHOD: # OF SAMPLES MICROARRAY NAME (SPECIES AND VERSION #) PROVIDED BY: QTY. REC.: USER FACILITY SAMPLE OR PLATE NAME CONC. VOL SAMPLE OR PLATE NAME CONC. VOL SAMPLE OR PLATE NAME CONC. VOL 1 5 9 2 6 10 3 7 11 4 8 12 *THE FACILITY IS NOT RESPONSIBLE FOR ANY SAMPLES THAT FAIL DUE TO INADEQUATE CONCENTRATION OR QUALITY. We assume ALL samples (including DNA for genotyping & methylation) submitted to us have met the posted recommendations listed on our website for processing. Sample terminated due to poor QC will still be subject to appropriate service charges. HIC APPROVED PROJECT? SOFTWARE TUTORIAL REQUESTED. NORMALIZATION METHOD REQUESTED: ALL SAMPLES MAY BE DISCARDED IF NOT RETRIEVED WITHIN 60 DAYS OF DATA POSTING. Sample forms without signatures will not be brought to West Campus. Apologies for any inconvenience. The samples listed above do not contain any of the following: radioactive material, hazardous chemicals (e.g. -

The Binding of Monoclonal and Polyclonal Anti-Z-DNA Antibodies to DNA of Various Species Origin

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article The Binding of Monoclonal and Polyclonal Anti-Z-DNA Antibodies to DNA of Various Species Origin Diane M. Spencer 1,2, Angel Garza Reyna 3 and David S. Pisetsky 1,2,* 1 Department of Medicine and Immunology, Division of Rheumatology, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC 27710, USA; [email protected] 2 Medical Research Service, Veterans Administration Medical Center, Durham, NC 27705, USA 3 Department of Chemistry, Duke University, Durham, NC 27705, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: DNA is a polymeric macromolecule that can display a variety of backbone conformations. While the classical B-DNA is a right-handed double helix, Z-DNA is a left-handed helix with a zig-zag orientation. The Z conformation depends upon the base sequence, base modification and supercoiling and is considered to be transient. To determine whether the presence of Z-DNA can be detected immunochemically, the binding of monoclonal and polyclonal anti-Z-DNA antibodies to a panel of natural DNA antigens was assessed by an ELISA using brominated poly(dG-dC) as a control for Z-DNA. As these studies showed, among natural DNA tested (Micrococcus luteus, calf thymus, Escherichia coli, salmon sperm, lambda phage), micrococcal (MC) DNA showed the highest binding with both anti-Z-DNA preparations, and E. coli DNA showed binding with the monoclonal anti-DNA preparation. The specificity for Z-DNA conformation in MC DNA was demonstrated by an inhibition binding assay. An algorithm to identify propensity to form Z-DNA indicated that Citation: Spencer, D.M.; Reyna, A.G.; Pisetsky, D.S. -

Arsenic Trioxide-Mediated Suppression of Mir-182-5P Is Associated with Potent Anti-Oxidant Effects Through Up-Regulation of SESN2

www.impactjournals.com/oncotarget/www.oncotarget.com Oncotarget, 2018,Oncotarget, Vol. 9, (No.Advance 22), Publicationspp: 16028-16042 2018 Research Paper Arsenic trioxide-mediated suppression of miR-182-5p is associated with potent anti-oxidant effects through up-regulation of SESN2 Liang-Ting Lin1,10,*, Shin-Yi Liu2,*, Jyh-Der Leu3,4,*, Chun-Yuan Chang1, Shih-Hwa Chiou5,6,7, Te-Chang Lee7,8 and Yi-Jang Lee1,9 1Department of Biomedical Imaging and Radiological Sciences, National Yang-Ming University, Taipei, Taiwan 2Department of Radiation Oncology, MacKay Memorial Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan 3Division of Radiation Oncology, Taipei City Hospital Ren Ai Branch, Taipei, Taiwan 4Institute of Neuroscience, National Chengchi University, Taipei, Taiwan 5Department of Medical Research and Education, Taipei Veterans General Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan 6Institute of Clinical Medicine, School of Medicine, National Yang-Ming University, Taipei, Taiwan 7Institute of Pharmacology, National Yang-Ming University, Taipei, Taiwan 8Institute of Biomedical Sciences, Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan 9Biophotonics and Molecular Imaging Research Center (BMIRC), National Yang-Ming University, Taipei, Taiwan 10Current address: Department of Health Technology and Informatics, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong *These authors have contributed equally to this work Correspondence to: Te-Chang Lee, email: [email protected] Yi-Jang Lee, email: [email protected] Keywords: arsenic trioxide; sestrin 2; miR-182; oxidative stress; anti-oxidant effect Received: April 12, 2017 Accepted: February 24, 2018 Published: March 23, 2018 Copyright: Lin et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0 (CC BY 3.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.