A Small Nucleolar RNA Is Processed from an Intron of the Human Gene Encoding Ribosomal Protein $3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comparison of the Effects on Mrna and Mirna Stability Arian Aryani and Bernd Denecke*

Aryani and Denecke BMC Research Notes (2015) 8:164 DOI 10.1186/s13104-015-1114-z RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access In vitro application of ribonucleases: comparison of the effects on mRNA and miRNA stability Arian Aryani and Bernd Denecke* Abstract Background: MicroRNA has become important in a wide range of research interests. Due to the increasing number of known microRNAs, these molecules are likely to be increasingly seen as a new class of biomarkers. This is driven by the fact that microRNAs are relatively stable when circulating in the plasma. Despite extensive analysis of mechanisms involved in microRNA processing, relatively little is known about the in vitro decay of microRNAs under defined conditions or about the relative stabilities of mRNAs and microRNAs. Methods: In this in vitro study, equal amounts of total RNA of identical RNA pools were treated with different ribonucleases under defined conditions. Degradation of total RNA was assessed using microfluidic analysis mainly based on ribosomal RNA. To evaluate the influence of the specific RNases on the different classes of RNA (ribosomal RNA, mRNA, miRNA) ribosomal RNA as well as a pattern of specific mRNAs and miRNAs was quantified using RT-qPCR assays. By comparison to the untreated control sample the ribonuclease-specific degradation grade depending on the RNA class was determined. Results: In the present in vitro study we have investigated the stabilities of mRNA and microRNA with respect to the influence of ribonucleases used in laboratory practice. Total RNA was treated with specific ribonucleases and the decay of different kinds of RNA was analysed by RT-qPCR and miniaturized gel electrophoresis. -

Human 28S Rrna 5' Terminal Derived Small RNA Inhibits Ribosomal Protein Mrna Levels Shuai Li 1* 1. Department of Breast Cancer

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/618520; this version posted April 25, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Human 28s rRNA 5’ terminal derived small RNA inhibits ribosomal protein mRNA levels Shuai Li 1* 1. Department of Breast Cancer Pathology and Research Laboratory, Tianjin Medical University Cancer Institute and Hospital, National Clinical Research Center for Cancer; Key Laboratory of Cancer Prevention and Therapy, Tianjin; Tianjin’s Clinical Research Center for Cancer, Tianjin 300060, China. * To whom correspondence should be addressed. Tel.: +86 22 23340123; Fax: +86 22 23340123; Email: [email protected] & [email protected]. bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/618520; this version posted April 25, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Abstract Recent small RNA (sRNA) high-throughput sequencing studies reveal ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs) as major resources of sRNA. By reanalyzing sRNA sequencing datasets from Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), we identify 28s rRNA 5’ terminal derived sRNA (named 28s5-rtsRNA) as the most abundant rRNA-derived sRNAs. These 28s5-rtsRNAs show a length dynamics with identical 5’ end and different 3’ end. Through exploring sRNA sequencing datasets of different human tissues, 28s5-rtsRNA is found to be highly expressed in bladder, macrophage and skin. We also show 28s5-rtsRNA is independent of microRNA biogenesis pathway and not associated with Argonaut proteins. Overexpression of 28s5-rtsRNA could alter the 28s/18s rRNA ratio and decrease multiple ribosomal protein mRNA levels. -

Fibrillarin from Archaea to Human

Biol. Cell (2015) 107, 1–16 DOI: 10.1111/boc.201400077 Review Fibrillarin from Archaea to human Ulises Rodriguez-Corona*, Margarita Sobol†, Luis Carlos Rodriguez-Zapata‡, Pavel Hozak† and Enrique Castano*1 *Unidad de Bioquımica´ y Biologıa´ molecular de plantas, Centro de Investigacion´ Cientıfica´ de Yucatan,´ Colonia Chuburna´ de Hidalgo, Merida,´ Yucatan, Mexico, †Department of Biology of the Cell Nucleus, Institute of Molecular Genetics of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Prague 14220, Czech Republic, and ‡Unidad de Biotecnologıa,´ Centro de Investigacion´ Cientıfica´ de Yucatan,´ Colonia Chuburna´ de Hidalgo, Merida,´ Yucatan, Mexico Fibrillarin is an essential protein that is well known as a molecular marker of transcriptionally active RNA polyme- rase I. Fibrillarin methyltransferase activity is the primary known source of methylation for more than 100 methylated sites involved in the first steps of preribosomal processing and required for structural ribosome stability. High expression levels of fibrillarin have been observed in several types of cancer cells, particularly when p53 levels are reduced, because p53 is a direct negative regulator of fibrillarin transcription. Here, we show fibrillarin domain conservation, structure and interacting molecules in different cellular processes as well as with several viral proteins during virus infection. Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher’s web-site Introduction progression, senescence and biogenesis of small nu- The nucleolus is the largest visible structure inside clear RNA and tRNAs proliferation and many forms the cell nucleus. It exists both as a dynamic and sta- of stress response (Andersen et al., 2005; Hinsby ble region depending of the nature and amount of et al., 2006; Boisvert et al., 2007; Shaw and Brown, the molecules that it is made of. -

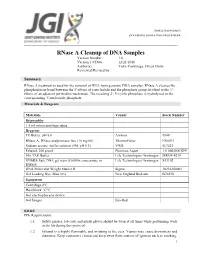

Rnase a Cleanup of DNA Samples Version Number: 1.0 Version 1.0 Date: 12/21/2016 Author(S): Yuko Yoshinaga, Eileen Dalin Reviewed/Revised By

SAMPLE MANAGEMENT STANDARD OPERATING PROCEDURE RNase A Cleanup of DNA Samples Version Number: 1.0 Version 1.0 Date: 12/21/2016 Author(s): Yuko Yoshinaga, Eileen Dalin Reviewed/Revised by: Summary RNase A treatment is used for the removal of RNA from genomic DNA samples. RNase A cleaves the phosphodiester bond between the 5'-ribose of a nucleotide and the phosphate group attached to the 3'- ribose of an adjacent pyrimidine nucleotide. The resulting 2', 3'-cyclic phosphate is hydrolyzed to the corresponding 3'-nucleoside phosphate. Materials & Reagents Materials Vendor Stock Number Disposables 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tubes Reagents TE Buffer, pH 8.0 Ambion 9849 RNase A, DNase and protease-free (10 mg/ml) ThermoFisher EN0531 Sodium acetate buffer solution (3M, pH 5.2) VWR 567422 Ethanol, 200 proof Pharmco-Aaper 111000200CSPP 50x TAE Buffer Life Technologies/ Invitrogen MRGF-4210 SYBR® Safe DNA gel stain (10,000x concentrate in Life Technologies/ Invitrogen S33102 DMSO) DNA Molecular Weight Marker II Sigma 10236250001 Gel Loading Dye, Blue (6x) New England BioLabs B7021S Equipment Centrifuge 4°C Heat block 37°C Gel electrophoresis device Gel Imager Bio-Rad EH&S PPE Requirements: 1.1 Safety glasses, lab coat, and nitrile gloves should be worn at all times while performing work in the lab during this protocol. 1.2 Ethanol is a highly flammable and irritating to the eyes. Vapors may cause drowsiness and dizziness. Keep containers closed and keep away from sources of ignition such as smoking. 1 SAMPLE MANAGEMENT STANDARD OPERATING PROCEDURE Avoid contact with skin and eyes. In case of contact with eyes, rinse immediately with plenty of water and seek medical advice. -

Global Analysis of Small RNA and Mrna Targets of Hfq

Blackwell Science, LtdOxford, UKMMIMolecular Microbiology 1365-2958Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 200350411111124Original ArticleA. Zhang et al.Global analysis of Hfq targets Molecular Microbiology (2003) 50(4), 1111–1124 doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03734.x Global analysis of small RNA and mRNA targets of Hfq Aixia Zhang,1 Karen M. Wassarman,2 greatly expanded over the past few years (reviewed in Carsten Rosenow,3 Brian C. Tjaden,4† Gisela Storz1* Gottesman, 2002; Grosshans and Slack, 2002; Storz, and Susan Gottesman5* 2002; Wassarman, 2002; Massé et al., 2003). A subset of 1Cell Biology and Metabolism Branch, National Institute of these small RNAs act via short, interrupted basepairing Child Health and Development, Bethesda MD 20892, interactions with target mRNAs. How do these small USA. RNAs find and anneal to their targets? In Escherichia coli, 2Department of Bacteriology, University of Wisconsin, at least part of the answer lies in their association with Madison, WI 53706, USA. and dependence upon the RNA chaperone, Hfq. The 3Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA 95051, USA. abundant Hfq protein was identified originally as a host 4Department of Computer Science, University of factor for RNA phage Qb replication (Franze de Fernan- Washington, Seattle, WA 98195, USA. dez et al., 1968), but later hfq mutants were found to 5Laboratory of Molecular Biology, National Cancer exhibit multiple phenotypes (Brown and Elliott, 1996; Muf- Institute, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA. fler et al., 1996). These defects are, at least in part, a reflection of the fact that Hfq is required for the function of several small RNAs including DsrA, RprA, Spot42, Summary OxyS and RyhB (Zhang et al., 1998; Sledjeski et al., Hfq, a bacterial member of the Sm family of RNA- 2001; Massé and Gottesman, 2002; Møller et al., 2002). -

Coupling of Spliceosome Complexity to Intron Diversity

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.19.436190; this version posted March 20, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Coupling of spliceosome complexity to intron diversity Jade Sales-Lee1, Daniela S. Perry1, Bradley A. Bowser2, Jolene K. Diedrich3, Beiduo Rao1, Irene Beusch1, John R. Yates III3, Scott W. Roy4,6, and Hiten D. Madhani1,6,7 1Dept. of Biochemistry and Biophysics University of California – San Francisco San Francisco, CA 94158 2Dept. of Molecular and Cellular Biology University of California - Merced Merced, CA 95343 3Department of Molecular Medicine The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA 92037 4Dept. of Biology San Francisco State University San Francisco, CA 94132 5Chan-Zuckerberg Biohub San Francisco, CA 94158 6Corresponding authors: [email protected], [email protected] 7Lead Contact 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.19.436190; this version posted March 20, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. SUMMARY We determined that over 40 spliceosomal proteins are conserved between many fungal species and humans but were lost during the evolution of S. cerevisiae, an intron-poor yeast with unusually rigid splicing signals. We analyzed null mutations in a subset of these factors, most of which had not been investigated previously, in the intron-rich yeast Cryptococcus neoformans. -

Secretariat of the CBD Technical Series No. 82 Convention on Biological Diversity

Secretariat of the CBD Technical Series No. 82 Convention on Biological Diversity 82 SYNTHETIC BIOLOGY FOREWORD To be added by SCBD at a later stage. 1 BACKGROUND 2 In decision X/13, the Conference of the Parties invited Parties, other Governments and relevant 3 organizations to submit information on, inter alia, synthetic biology for consideration by the Subsidiary 4 Body on Scientific, Technical and Technological Advice (SBSTTA), in accordance with the procedures 5 outlined in decision IX/29, while applying the precautionary approach to the field release of synthetic 6 life, cell or genome into the environment. 7 Following the consideration of information on synthetic biology during the sixteenth meeting of the 8 SBSTTA, the Conference of the Parties, in decision XI/11, noting the need to consider the potential 9 positive and negative impacts of components, organisms and products resulting from synthetic biology 10 techniques on the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity, requested the Executive Secretary 11 to invite the submission of additional relevant information on this matter in a compiled and synthesised 12 manner. The Secretariat was also requested to consider possible gaps and overlaps with the applicable 13 provisions of the Convention, its Protocols and other relevant agreements. A synthesis of this 14 information was thus prepared, peer-reviewed and subsequently considered by the eighteenth meeting 15 of the SBSTTA. The documents were then further revised on the basis of comments from the SBSTTA 16 and peer review process, and submitted for consideration by the twelfth meeting of the Conference of 17 the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity. -

U6 Small Nuclear RNA Is Transcribed by RNA Polymerase III (Cloned Human U6 Gene/"TATA Box"/Intragenic Promoter/A-Amanitin/La Antigen) GARY R

Proc. Nati. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 83, pp. 8575-8579, November 1986 Biochemistry U6 small nuclear RNA is transcribed by RNA polymerase III (cloned human U6 gene/"TATA box"/intragenic promoter/a-amanitin/La antigen) GARY R. KUNKEL*, ROBIN L. MASERt, JAMES P. CALVETt, AND THORU PEDERSON* *Cell Biology Group, Worcester Foundation for Experimental Biology, Shrewsbury, MA 01545; and tDepartment of Biochemistry, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS 66103 Communicated by Aaron J. Shatkin, August 7, 1986 ABSTRACT A DNA fragment homologous to U6 small 4A (20) was screened with a '251-labeled U6 RNA probe (21, nuclear RNA was isolated from a human genomic library and 22) using a modified in situ plaque hybridization protocol sequenced. The immediate 5'-flanking region of the U6 DNA (23). One of several positive clones was plaque-purified and clone had significant homology with a potential mouse U6 gene, subsequently shown by restriction mapping to contain a including a "TATA box" at a position 26-29 nucleotides 12-kilobase-pair (kbp) insert. A 3.7-kbp EcoRI fragment upstream from the transcription start site. Although this containing U6-hybridizing sequences was subcloned into sequence element is characteristic of RNA polymerase II pBR322 for further restriction mapping. An 800-base-pair promoters, the U6 gene also contained a polymerase III "box (bp) DNA fragment containing U6 homologous sequences A" intragenic control region and a typical run of five thymines was excised using Ava I and inserted into the Sma I site of at the 3' terminus (noncoding strand). The human U6 DNA M13mp8 replicative form DNA (M13/U6) (24). -

Protein-Free Small Nuclear Rnas Catalyze a Two-Step Splicing Reaction

Protein-free small nuclear RNAs catalyze a two-step splicing reaction Saba Valadkhan1,2, Afshin Mohammadi1, Yasaman Jaladat, and Sarah Geisler Center for RNA Molecular Biology, Case Western Reserve University, 10900 Euclid Avenue, Cleveland, OH 44106 Edited by Joan A. Steitz, Yale University, New Haven, CT, and approved May 13, 2009 (received for review March 3, 2009) Pre-mRNA splicing is a crucial step in eukaryotic gene expression and is carried out by a highly complex ribonucleoprotein assembly, the spliceosome. Many fundamental aspects of spliceosomal function, including the identity of catalytic domains, remain unknown. We show that a base-paired complex of U6 and U2 small nuclear RNAs, in the absence of the Ϸ200 other spliceosomal components, performs a two-step reaction with two short RNA oligonucleotides as substrates that results in the formation of a linear RNA product containing portions of both oligonucleotides. This reaction, which is chemically identical to splicing, is dependent on and occurs in proximity of sequences known to be critical for splicing in vivo. These results prove that the complex formed by U6 and U2 RNAs is a ribozyme and can potentially carry out RNA-based catalysis in the spliceosome. catalysis ͉ ribozymes ͉ snRNAs ͉ spliceosome ͉ U6 xtensive mechanistic and structural similarities between spliceoso- BIOCHEMISTRY Emal small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs) and self-splicing group II introns (1, 2) have led to the hypothesis that the snRNAs are evolu- Fig. 1. The U6/U2 complex and splicing substrates. (A) The U6/U2 construct used tionary descendents of group II–like introns and thus could similarly in this study, which contains the central domains of the human U6 and U2 snRNAs. -

Nuclear Expression of a Group II Intron Is Consistent with Spliceosomal Intron Ancestry

Downloaded from genesdev.cshlp.org on September 30, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Nuclear expression of a group II intron is consistent with spliceosomal intron ancestry Venkata R. Chalamcharla, M. Joan Curcio, and Marlene Belfort1 Center for Medical Sciences, Wadsworth Center, New York State Department of Health, Albany, New York 12208, USA; and School of Public Health, State University of New York at Albany, Albany, New York 12201, USA Group II introns are self-splicing RNAs found in eubacteria, archaea, and eukaryotic organelles. They are mechanistically similar to the metazoan nuclear spliceosomal introns; therefore, group II introns have been invoked as the progenitors of the eukaryotic pre-mRNA introns. However, the ability of group II introns to function outside of the bacteria-derived organelles is debatable, since they are not found in the nuclear genomes of eukaryotes. Here, we show that the Lactococcus lactis Ll.LtrB group II intron splices accurately and efficiently from different pre-mRNAs in a eukaryote, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. However, a pre-mRNA harboring a group II intron is spliced predominantly in the cytoplasm and is subject to nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD), and the mature mRNA from which the group II intron is spliced is poorly translated. In contrast, a pre-mRNA bearing the Tetrahymena group I intron or the yeast spliceosomal ACT1 intron at the same location is not subject to NMD, and the mature mRNA is translated efficiently. Thus, a group II intron can splice from a nuclear transcript, but RNA instability and translation defects would have favored intron loss or evolution into protein-dependent spliceosomal introns, consistent with the bacterial group II intron ancestry hypothesis. -

Mediator Is Essential for Small Nuclear and Nucleolar RNA Transcription in Yeast

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/352906; this version posted June 21, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 Mediator is essential for small nuclear and nucleolar RNA transcription in yeast 2 3 Jason P. Tourignya, Moustafa M. Saleha, Gabriel E. Zentnera# 4 5 aDepartment of Biology, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, USA 6 7 #Address correspondence to Gabriel E. Zentner, [email protected] 8 9 Running head: Mediator regulates sn/snoRNAs 10 11 Abstract word count: 198 12 Introduction/results/discussion word count: 3,085 13 Materials and methods word count: 1,433 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/352906; this version posted June 21, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 14 Abstract 15 Eukaryotic RNA polymerase II (RNAPII) transcribes mRNA genes as well as non-protein coding 16 RNAs (ncRNAs) including small nuclear and nucleolar RNAs (sn/snoRNAs). In metazoans, 17 RNAPII transcription of sn/snoRNAs is facilitated by a number of specialized complexes, but no 18 such complexes have been discovered in yeast. It has thus been proposed that yeast 19 sn/snoRNA promoters use the same complement of factors as mRNA promoters, but the extent 20 to which key regulators of mRNA genes act at sn/snoRNA genes in yeast is unclear. -

The Nucleolus – a Gateway to Viral Infection? Brief Review

Arch Virol (2002) 147: 1077–1089 DOI 10.1007/s00705-001-0792-0 The nucleolus – a gateway to viral infection? Brief Review J. A. Hiscox School of Animal and Microbial Sciences, University of Reading, U.K. Received August 24, 2001; accepted December 26, 2001 Published online March 18, 2002, © Springer-Verlag 2002 Summary. A number of viruses and viral proteins interact with a dynamic sub- nuclear structure called the nucleolus. The nucleolus is present during interphase in mammalian cells and is the site of ribosome biogenesis, and has been implicated in controlling regulatory processes such as the cell cycle. Viruses interact with the nucleolus and its antigens; viral proteins co-localise with factors such as nucleolin, B23 and fibrillarin, and can cause their redistribution during infection. Viruses can use these components as part of their replication process, and also use the nucleolus as a site of replication itself. Many of these properties are not restricted to any particular type of virus or replication mechanism, and examples of these processes can be found in DNA, RNA and retroviruses. Evidence suggests that viruses may target the nucleolus and its components to favour viral transcription, translation and perhaps alter the cell cycle in order to promote virus replication. Autoimmunity to nucleolin and fibrillarin have been associated with a number of diseases, and by targeting the nucleolus and displacing nucleolar antigens, virus infection might play a role in the initiation of these conditions. Introduction The eukaryotic nucleus contains a number of domains or subcompartments, which include nucleoli, nuclear Cajal bodies, nuclear speckles, transcription and replica- tion foci, and chromosome territories [34].