The Conservation Status of Birds on the Cordillera De Colan, Peru

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Comprehensive Multilocus Phylogeny of the Neotropical Cotingas

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 81 (2014) 120–136 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev A comprehensive multilocus phylogeny of the Neotropical cotingas (Cotingidae, Aves) with a comparative evolutionary analysis of breeding system and plumage dimorphism and a revised phylogenetic classification ⇑ Jacob S. Berv 1, Richard O. Prum Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University, P.O. Box 208105, New Haven, CT 06520, USA article info abstract Article history: The Neotropical cotingas (Cotingidae: Aves) are a group of passerine birds that are characterized by Received 18 April 2014 extreme diversity in morphology, ecology, breeding system, and behavior. Here, we present a compre- Revised 24 July 2014 hensive phylogeny of the Neotropical cotingas based on six nuclear and mitochondrial loci (7500 bp) Accepted 6 September 2014 for a sample of 61 cotinga species in all 25 genera, and 22 species of suboscine outgroups. Our taxon sam- Available online 16 September 2014 ple more than doubles the number of cotinga species studied in previous analyses, and allows us to test the monophyly of the cotingas as well as their intrageneric relationships with high resolution. We ana- Keywords: lyze our genetic data using a Bayesian species tree method, and concatenated Bayesian and maximum Phylogenetics likelihood methods, and present a highly supported phylogenetic hypothesis. We confirm the monophyly Bayesian inference Species-tree of the cotingas, and present the first phylogenetic evidence for the relationships of Phibalura flavirostris as Sexual selection the sister group to Ampelion and Doliornis, and the paraphyly of Lipaugus with respect to Tijuca. -

Northern Peru’S Cloud Forest Endemics Mythical Owlet and the Stupendous Spatuletail! August 12-23, 2021 ©2020

Northern Peru’s Cloud Forest Endemics Mythical Owlet and the Stupendous Spatuletail! August 12-23, 2021 ©2020 This tour takes full advantage of the impressive and comfortable Owlet ecotourism lodge, at Abra Patricia where we will stay for seven nights maximizing our exciting Andean birding time. Its location is perfect, situated within the huge Alto Mayo Cloud Forest Reserve created in 1987, protecting an immense area covering 1,820 square kilometers (450,000 acres) of wondrous cloud forest along the upper Mayo River just brimming with exotic Andean life. This in fact is a fabled birding area full of colorful cloud forest birds including many exciting endemics and poorly-know species along with hordes of colorful Tanagers and hummingbirds galore allowing for a unique opportunity of fabulous birding right from our doorsteps! Marvelous Spatuletail (male) © Andrew Whittaker The Owlet Lodge is set in a pristine cloud forest at 2300 m (7500 feet) offering cool climate, excellent food, a well-constructed canopy tower, loads of active hummingbird feeders, plus one of the best kept Andean forest trail systems ever! Combine this with the nearby Asociacion Ecosistemas Andinos Reserve (ECOAN) specifically dedicated to the endemic Marvelous Spatulatetail, as well as many other exciting hummingbird species found at the feeders. This tour is excellent for endemics and be prepared for an overload of other colorful Andean birds, plus an incredible diversity of the much-loved glowing hummingbirds, and of course spectacular and colorful mountain tanager flocks. Northern Peru’s Cloud Forest: Page 2 At Waquanki Lodge, we will have an exciting couple of nights in this lovely, fairly new, family run lodge, located in forested grounds of the foothills, at about 900 m (3000 feet), near the village of Moyobamba. -

Ultimate Bolivia Tour Report 2019

Titicaca Flightless Grebe. Swimming in what exactly? Not the reed-fringed azure lake, that’s for sure (Eustace Barnes) BOLIVIA 8 – 29 SEPTEMBER / 4 OCTOBER 2019 LEADER: EUSTACE BARNES Bolivia, indeed, THE land of parrots as no other, but Cotingas as well and an astonishing variety of those much-loved subfusc and generally elusive denizens of complex uneven surfaces. Over 700 on this tour now! 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Ultimate Bolivia 2019 www.birdquest-tours.com Blue-throated Macaws hoping we would clear off and leave them alone (Eustace Barnes) Hopefully, now we hear of colourful endemic macaws, raucous prolific birdlife and innumerable elusive endemic denizens of verdant bromeliad festooned cloud-forests, vast expanses of rainforest, endless marshlands and Chaco woodlands, each ringing to the chorus of a diverse endemic avifauna instead of bleak, freezing landscapes occupied by impoverished unhappy peasants. 2 BirdQuest Tour Report: Ultimate Bolivia 2019 www.birdquest-tours.com That is the flowery prose, but Bolivia IS that great destination. The tour is no longer a series of endless dusty journeys punctuated with miserable truck-stop hotels where you are presented with greasy deep-fried chicken and a sticky pile of glutinous rice every day. The roads are generally good, the hotels are either good or at least characterful (in a good way) and the food rather better than you might find in the UK. The latter perhaps not saying very much. Palkachupe Cotinga in the early morning light brooding young near Apolo (Eustace Barnes). That said, Bolivia has work to do too, as its association with that hapless loser, Che Guevara, corruption, dust and drug smuggling still leaves the country struggling to sell itself. -

Trends in Nectar Concentration and Hummingbird Visitation

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2016 Trends in Nectar Concentration and Hummingbird Visitation: Investigating different variables in three flowers of the Ecuadorian Cloud Forest: Guzmania jaramilloi, Gasteranthus quitensis, and Besleria solanoides Sophie Wolbert SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Animal Studies Commons, Community-Based Research Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, Latin American Studies Commons, and the Plant Biology Commons Recommended Citation Wolbert, Sophie, "Trends in Nectar Concentration and Hummingbird Visitation: Investigating different variables in three flowers of the Ecuadorian Cloud Forest: Guzmania jaramilloi, Gasteranthus quitensis, and Besleria solanoides" (2016). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 2470. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/2470 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Wolbert 1 Trends in Nectar Concentration and Hummingbird Visitation: Investigating different variables in three flowers of the Ecuadorian Cloud Forest: Guzmania jaramilloi, Gasteranthus quitensis, and Besleria solanoides Author: Wolbert, Sophie Academic -

Download Download

Journal of Caribbean Ornithology RESEARCH ARTICLE Vol. 33:1–14. 2020 Composition of bird community in Portachuelo Pass (Henri Pittier National Park, Venezuela) Cristina Sainz-Borgo Jhonathan Miranda Miguel Lentino Photo: Pedro Arturo Amaro Journal of Caribbean Ornithology jco.birdscaribbean.org ISSN 1544-4953 RESEARCH ARTICLE Vol. 33:1–14. 2020 birdscaribbean.org Composition of bird community in Portachuelo Pass (Henri Pittier National Park, Venezuela) Cristina Sainz-Borgo1, Jhonathan Miranda2, and Miguel Lentino3 Abstract The purpose of this study was to describe the composition of the bird community in Portachuelo Pass, located in Henri Pittier National Park, Venezuela. Portachuelo Pass is an important route for migratory birds between northern South America and the Southern Cone. During 11 months of sampling between 2010 and 2012, we captured 1,460 birds belonging to 125 identified species, 29 families, and 9 orders. The families with the highest relative abundance and species richness were Trochilidae and Thraupidae and the most common species were the Violet-chested Hummingbird (Sternoclyta cyanopectus), Olive-striped Flycatcher (Mionectes olivaceus), Plain-brown Woodcreeper (Dendrocincla fuliginosa), Orange-bellied Euphonia (Euphonia xanthogaster), Violet-fronted Brilliant (Heliodoxa leadbeateri), Vaux’s Swift (Chaetura vauxi), Red-eared Parakeet (Pyrrhura hoematotis), Golden-tailed Sapphire (Chrysuronia oenone), Black-hooded Thrush (Turdus olivater), and Gray-rumped Swift (Chaetura cinereiventris). These species represented 52.4% of total captures and 8.0% of identified species. We captured 5 endemic species and 8 migratory species. The months of greatest relative abundance and species richness were June and July 2010 and January 2011. Birds captured belonged to the following feeding guilds: insectivorous, nectarivorous-insectivorous, frugivorous, frugivorous-insectivorous, granivorous, frugivorous-folivorous, omnivorous, carnivorous, and frugivorous-graniv- orous. -

List of the Birds of Peru Lista De Las Aves Del Perú

LIST OF THE BIRDS OF PERU LISTA DE LAS AVES DEL PERÚ By/por MANUEL A. -

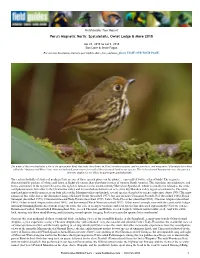

Spatuletails, Owlet Lodge & More 2018

Field Guides Tour Report Peru's Magnetic North: Spatuletails, Owlet Lodge & More 2018 Jun 23, 2018 to Jul 5, 2018 Dan Lane & Jesse Fagan For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. The name of this tour highlights a few of the spectacular birds that make their homes in Peru's northern regions, and we saw these, and many more! This might have been called the "Antpittas and More" tour, since we had such great views of several of these formerly hard-to-see species. This Ochre-fronted Antpitta was one; she put on a fantastic display for us! Photo by participant Linda Rudolph. The eastern foothills of Andes of northern Peru are one of those special places on the planet… especially if you’re a fan of birds! The region is characterized by pockets of white sand forest at higher elevations than elsewhere in most of western South America. This translates into endemism, and hence our interest in the region! Of course, the region is famous for the award-winning Marvelous Spatuletail, which is actually not related to the white sand phenomenon, but rather to the Utcubamba valley and its rainshadow habitats (an arm of the dry Marañon valley region of endemism). The white sand endemics actually span areas on both sides of the Marañon valley and include several species described to science only since about 1976! The most famous of this collection is the diminutive Long-whiskered Owlet (described 1977), but also includes Cinnamon Screech-Owl (described 1986), Royal Sunangel (described 1979), Cinnamon-breasted Tody-Tyrant (described 1979), Lulu’s Tody-Flycatcher (described 2001), Chestnut Antpitta (described 1987), Ochre-fronted Antpitta (described 1983), and Bar-winged Wood-Wren (described 1977). -

Crested Quetzal (Pharomachrus Antisianus) Preying on a Glassfrog (Anura, Centrolenidae) in Sierra De Perijá, Northwestern Venezuela

Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia, 22(4), 419-421 SHORTCOMMUNICATION December 2014 Crested Quetzal (Pharomachrus antisianus) preying on a Glassfrog (Anura, Centrolenidae) in Sierra de Perijá, northwestern Venezuela Marcial Quiroga-Carmona1,3 and Adrián Naveda-Rodríguez2 1 Centro de Ecología, Instituto Venezolano de Investigaciones Científicas, Caracas 1020-A, Apartado 2032, Venezuela. 2 The Peregrine Fund, 5668 West Flying Hawk Lane, Boise, ID 83709, U.S.A. 3 Corresponding author: [email protected] Received on 17 September 2014. Accepted on 8 November 2014. ABSTRACT: We report the predation of a glassfrog (Hyalinobatrachium pallidum) by a Crested Quetzal (Pharomachrus antisianus). The record was made in a locality in the Sierra de Perijá, near to the northern part of the border between Colombia and Venezuela, and consisted in observinga male P. antisianus vocalizing with a glassfrog in its bill. The vocalizations were answered by a female, which approached the male, took the frog with its bill and carried it into a cavity built on a landslide. Subsequent to this, the male remained near to the cavity until the female left it and together they abandoned this place. Based on the behavior observed in the couple of quetzals, and what has previously been described that this group of birds gives their young a diet rich in animal protein comprised of arthropods and small vertebrates, we believe that the couple was raising a brood at the time when the observation was carried out. KEYWORDS: Anurophagy, diet, Hyalinobatrachium, Trogonidae, Trogoniformes. The consumption of animal protein is a behavior a behavior also reported for P. pavoninus (Lebbin 2007) exhibited by most of the species of the family Trogonidae. -

Birding in Southern Ecuador February 11 – 27, 2016 TRIP REPORT Folks

Mass Audubon’s Natural History Travel and Joppa Flats Education Center Birding in Southern Ecuador February 11 – 27, 2016 TRIP REPORT Folks, Thank you for participating in our amazing adventure to the wilds of Southern Ecuador. The vistas were amazing, the lodges were varied and delightful, the roads were interesting— thank goodness for Jaime, and the birds were fabulous. With the help of our superb guide Jose Illanes, the group managed to amass a total of 539 species of birds (plus 3 additional subspecies). Everyone helped in finding birds. You all were a delight to travel with, of course, helpful to the leaders and to each other. This was a real team effort. You folks are great. I have included your top birds, memorable experiences, location summaries, and the triplist in this document. I hope it brings back pleasant memories. Hope to see you all soon. Dave David M. Larson, Ph.D. Science and Education Coordinator Mass Audubon’s Joppa Flats Education Center Newburyport, MA 01950 Top Birds: 1. Jocotoco Antpitta 2-3. Solitary Eagle and Orange-throated Tanager (tied) 4-7. Horned Screamer, Long-wattled Umbrellabird, Rainbow Starfrontlet, Torrent Duck (tied) 8-15. Striped Owl, Band-winged Nightjar, Little Sunangel, Lanceolated Monklet, Paradise Tanager, Fasciated Wren, Tawny Antpitta, Giant Conebill (tied) Honorable mention to a host of other birds, bird groups, and etc. Memorable Experiences: 1. Watching the diving display and hearing the vocalizations of Purple-collared Woodstars and all of the antics, colors, and sounds of hummers. 2. Learning and recognizing so many vocalizations. 3. Experiencing the richness of deep and varied colors and abundance of birds. -

Practical-Actions-Report.Pdf

CONTENIDO I.- INTRODUCCIÓN ........................................................................................................................ 5 II. OBJETIVOS DEL ESTUDIO .......................................................................................................... 6 III.- UBICACIÓN DEL ÁREA DE ESTUDIO ....................................................................................... 6 III.- MARCO REFERENCIAL ............................................................................................................ 9 IV.- MATERIALES Y MÉTODOS .................................................................................................... 12 4.1. MATERIALES ..................................................................................................................... 12 4.2. MÉTODOS ........................................................................................................................ 14 4.2.1. ANÁLISIS CARTOGRÁFICO DE LA ZONA ................................................................... 14 4.2.2. PRESENCIA DE ESPECIES CLAVE ................................................................................ 16 4.2.3. IDENTIFICACIÓN DE LA DIETA DE LAS ESPECIES CLAVE .......................................... 28 4.2.4. CAPACITACIÓN A GUÍA LOCALES ............................................................................. 29 5.1. PRESENCIA DE ESPECIES CLAVE ....................................................................................... 31 5.1.1. Determinación de presencia mediante -

Paul Mcbride a Thesis Submitted to Auckland University of Technology

Paul McBride A thesis submitted to Auckland University of Technology in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) 2015 Institute for Applied Ecology New Zealand School of Applied Sciences Faculty of Health and Environmental Sciences i The density of species varies widely across the earth. Most broad taxonomic groups have similar spatial diversity patterns, with greatest densities of species in wet, tropical environments. Although evidently correlated with climate, determining the causes of such diversity differences is complicated by myriad factors: many possible mechanisms exist to link climate and diversity, these mechanisms are not mutually exclusive, and they may overlap in the patterns they generate. Further, the importance of different mechanisms may vary between spatial scales. Generating uneven spatial diversity patterns in regions that are below equilibrium species richness requires either geometric or historical area effects, or regional differences in net diversification. Here, I investigate the global climate correlates of diversity in plants and vertebrates, and hypotheses that could link these correlates to net diversification processes, in particular through climate-linked patterns of molecular evolution. I first show strong climate–diversity relationships only emerge at large scales, and that the specific correlates of diversity differ between plants and animals. For plants, the strongest large-scale predictor of species richness is net primary productivity, which reflects the water–energy balance at large scales. For animals, temperature seasonality is the strongest large-scale predictor of diversity. Then, using two clades of New World passerine birds that together comprise 20% of global avian diversity, I investigate whether rates and patterns of molecular evolution can be linked to diversification processes that could cause spatial diversity patterns in birds. -

Supplemental Wing Shape and Dispersal Analysis

Data Supplement High dispersal ability inhibits speciation in a continental radiation of passerine birds Santiago Claramunt, Elizabeth P. Derryberry, J. V. Remsen, Jr. & Robb T. Brumfield Museum of Natural Science and Department of Biological Sciences, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA 70803, USA HAND-WING INDEX AND FLIGHT PERFORMANCE IN NEOTROPICAL FOREST BIRDS We investigated the relationship between wing shape and flight distances determined during 'dispersal challenge' experiments conducted in Gatun Lake in the Panama Canal (Moore et al. 2008). During the experiments, birds were released from a boat at incremental distances from shore and the distance flown or the success or failure in reaching the coast was recorded. To investigated the relationship between the hand-wing index and flight distance in Neotropical birds we used data on mean distance flown from table 3 in ref. We estimated hand-wing indices for the 10 species reported in those experiments (Table S1) . Wing measurements were taken by SC for four males of each species at LSUMNS. The relationship between the hand-wing index and distance flown was evaluated statistically using phylogenetic generalized least-squares (PGLS, Freckleton et al. 2002). We generated a phylogeny for the species involved in the experiment or an appropriate surrogate using DNA sequences of the slow-evolving RAG 1 gene from GenBank (Table S2). A maximum likelihood ultrametric tree was generated in PAUP* (Swofford 2003) using a GTR+! model of nucleotide substitution rates, empirical nucleotide frequencies, and enforcing a molecular clock. We found that the hand-wing index was strongly related to mean distance flown (R2 = 0.68, F = 20, d.f.