Cry of Jazz by Chuck Kleinhans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Sonic Retro-Futures: Musical Nostalgia as Revolution in Post-1960s American Literature, Film and Technoculture Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/65f2825x Author Young, Mark Thomas Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Sonic Retro-Futures: Musical Nostalgia as Revolution in Post-1960s American Literature, Film and Technoculture A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Mark Thomas Young June 2015 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Sherryl Vint, Chairperson Dr. Steven Gould Axelrod Dr. Tom Lutz Copyright by Mark Thomas Young 2015 The Dissertation of Mark Thomas Young is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS As there are many midwives to an “individual” success, I’d like to thank the various mentors, colleagues, organizations, friends, and family members who have supported me through the stages of conception, drafting, revision, and completion of this project. Perhaps the most important influences on my early thinking about this topic came from Paweł Frelik and Larry McCaffery, with whom I shared a rousing desert hike in the foothills of Borrego Springs. After an evening of food, drink, and lively exchange, I had the long-overdue epiphany to channel my training in musical performance more directly into my academic pursuits. The early support, friendship, and collegiality of these two had a tremendously positive effect on the arc of my scholarship; knowing they believed in the project helped me pencil its first sketchy contours—and ultimately see it through to the end. -

4823C7a9d589da82e72837249d

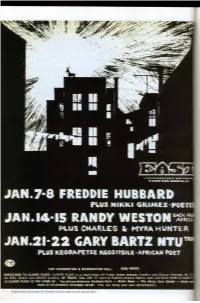

RETURN TO THE EAST BROOKLYN RECLRIMS THE BLRCK RRT FORM KNOWN RS JRZZ I' IIlII£I SCIIII£I • B9 BllSIl MCHBII 'What you're about to hear is not jazz, or some other irrelevant term we allow others 10 use in defining our creation, but the sounds thai are about to saturate your being and serlsitize your soul is the continuing process of nationalist consciousness manifesting its message within the conlext of one of our strongest natural resources: Black music. What is represented on these jams is the crystallization of the role of Black music as a functional organ in the struggle for national liberation.. AJkebu-lan is the unfolding of this progress as mu!>ic-meaoing. It is sound-feeling." KwmbI. >PUI<Irc .... -_. on SUN-Uol his lpOkrn.word innoduuion amounl$ 10 :l m:o.ni- Kwasi Konadu'l r«mt book, Trulh Cru.sJKJ It> tIN &nh rrd:o.iming tlK Black nl form known u WiU RiM Api.., is the delining tome on lhe Ezsr.. h details T for uS/: ali :o.libn:aling. II2l1"P"rti..., vdlic:k. '1M do- lhecompln worIrinV ofhow the organiulion flourished for qurnl <kKript ion ofil :oJ :l -funuion,,1 organ- ckserillQ 1M o>'n adead... 1hc wt and iu primary k>c:o.tion at ,00aver mk of$('lUnd wilhin m.- Ezsr. organiu.ion wdl. MllSic Plac:c in Brooklyn WU n(K just a norefrom or musk hall, bul the blood pumping, mako i. as;"r m dig"". and a w::o.yoflifc.lhc Uhunf Food asan or. -

HISTORY of JAZZ II – 1St

HISTORY OF JAZZ II MUZ2339W –Semester One Class Notes By Prof M.J. Rossi Hard Bop Hard bop – term applied to hard driving, intense style of jazz in the 1950s- 60s. Art Blakey, Horace Silver, Cannonball Adderley, Sonny Rollins extended to encompass the music of Miles Davis, J.J. Johnson, Art Farmer – Benny Golson. Dark weighty textures, soulful inflections, blues like melodic figures, chord progressions borrowed form the black church, louder more interactive drumming, more facile bass playing, drew less on forms of the previous period. Most players were African-Americans and came out of Philadelphia and Detroit. Best remembered tunes: Senor Blues, Song for My Father – Horace Silver Work Song – Nat Adderely, Mercy, Mercy, Mercy – Joe Zawinul The Sidewinder – Lee Morgan Watermelon Man – Herbie Hancock The Birth of Hard Bop (Jazz: The First Century, pgs 115-117) The cool school had offered a reaction to bebop, but in New York, Chicago, Philadelphia and Detroit, the jazz of the 1950s derived primarily from bebop to become the style called hard bop. The Miles Davis recordings of “Four” (1954) and “Walkin’ (1954) suggest the arrival of hard bop, the real parents were Art Blakey and Horace Silver. In the summer of 1954 both formed a cooperative quintet, the Jazz Messengers, and in 1955 they recorded a jubilant shout in the form of the 16-bar blues “The Preacher”, composed by Silver, as Goldberg states, “The reaction to the reaction had taken place.”. To be sure, the hard boppers were responding to cool’s constraints with their emotionalism. But they were also reacting to the calcinations of bebop. -

Sun Ra and the Performance of Reckoning

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2015 "The planet is the way it is because of the scheme of words": Sun Ra and the Performance of Reckoning Maryam Ivette Parhizkar Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1086 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] "THE PLANET IS THE WAY IT IS BECAUSE OF THE SCHEME OF WORDS": SUN RA AND THE PERFORMANCE OF RECKONING BY MARYAM IVETTE PARHIZKAR A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York. 2015 i This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in satisfaction of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. Thesis Adviser: ________________________________________ Ammiel Alcalay Date: ________________________________________ Executive Officer: _______________________________________ Matthew K. Gold Date: ________________________________________ THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK ii Abstract "The Planet is the Way it is Because of the Scheme of Words": Sun Ra and the Performance of Reckoning By Maryam Ivette Parhizkar Adviser: Ammiel Alcalay This constellatory essay is a study of the African American sound experimentalist, thinker and self-proclaimed extraterrestrial Sun Ra (1914-1993) through samplings of his wide, interdisciplinary archive: photographs, film excerpts, selected recordings, and various interviews and anecdotes. -

Chicago Jazz Visionaries Mike Reed and Jason Adasiewicz Perform Musical Alchemy in New Myth/Old Science, Transforming Discarde

Bio information: LIVING BY LANTERNS Title: NEW MYTH/OLD SCIENCE (Cuneiform Rune 345) Format: CD / LP Cuneiform publicity/promotion dept.: 301-589-8894 / fax 301-589-1819 email: joyce [-at-] cuneiformrecords.com (Press & world radio); radio [-at-] cuneiformrecords.com (North American & world radio) www.cuneiformrecords.com FILE UNDER: JAZZ / AVANT-JAZZ Chicago Jazz Visionaries Mike Reed and Jason Adasiewicz Perform Musical Alchemy in New Myth/Old Science, Transforming Discarded Sun Ra Rehearsal Tape Into Improvisational Gold with their group Living By Lanterns, An All-Star Nine-Piece Ensemble, Featuring a Mighty Cast of Young Chicago & New York Masters According to some versions of String Theory, ours is but one of an infinite number of universes. But you would need to dig deeply into the cosmological haystack before encountering a project as extraordinary and unlikely as New Myth/Old Science, which brings together an incandescent cast of Chicago and New York improvisers to explore music inspired by a previously unknown recording of Sun Ra. In the hands of drummer Mike Reed and vibraphonist Jason Adasiewicz, who are both invaluable and protean creative forces on Chicago’s vibrant new music scene, Ra’s informal musings serve as a portal for their cohesive but multi-dimensional combo, newly christened Living By Lanterns. Commissioned by Experimental Sound Studio (ESS), the music is one of several projects created in response to material contained in ESS’s vast Sun Ra/El Saturn Audio Archive. Rather than a Sun Ra tribute, Reed and Adasiewicz have crafted a melodically rich, harmonically expansive body of themes orchestrated from fragments extracted from a rehearsal tape marked “NY 1961,” featuring Ra on electric piano, John Gilmore on tenor sax and flute, and Ronnie Boykins on bass. -

Sun Ra Egypt

Sun Ra Egypt '71 (5x LP box set ) 5LP K7/Strut Marcy Luarks & Classic Touch Electric Murder (LP) LP K7/Kalita Records Ace Of Base The Sign (7" picture disc ) ACE7 7" K7/!K7 Records Phoebe Killdeer The Fade Out Line (12" Picture Disc ) 12" K7/Kwaidan Records Strut Records Artist: Sun Ra Title: Egypt '71 Format: 5x LP box set In December 1971, Sun Ra made an impromptu trip to Egypt with his Arkestra, his first time in the country. Hosted by drummer Salah Ragab and Goethe Institute's Hartmut Geerken, they performed hastily arranged concerts at Ballon Theatre in Cairo and at Geerken's house in Heliopolis. The performances emerged on three LPs released by Ra during the '70s: 'Horizon', 'Nidhamu' and 'Dark Myth Visitation Equation'. These three LPs now receive their first reissue on vinyl alongside 2 LPs of previously unreleased recordings. Rare photos and extensive new liner notes by Geerken and Paul Griffiths complete a definitive package celebrating Sun Ra's iconic trip to the Land of Ra. First vinyl reissue + 2 xLP previously unreleased !K7 Records Artist: Ace Of Base Title: The Sign Format: 7" picture disc "The Sign" is a song by the Swedish band Ace of Base, which was released on 29 October 1993 in Europe. It was an international hit, reaching number two in the United Kingdom and spending six non-consecutive weeks at number one on the Billboard Hot 100 chart in the United States. More prominently, it became the top song on Billboard's 1994 Year End Chart. It appeared on the band's album Happy Nation (titled The Sign in North America). -

Blues in the Blood a M U E S L B M L E O O R D

March 2011 | No. 107 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com J blues in the blood a m u e s l b m l e o o r d Johnny Mandel • Elliott Sharp • CAP Records • Event Calendar In his play Romeo and Juliet, William Shakespeare wrote, “A rose by any other name would smell as sweet.” It is a lovely sentiment but one with which we agree only partially. So with that introduction, we are pleased to announce that as of this issue, the gazette formerly known as AllAboutJazz-New York will now be called The New York City Jazz Record. It is a change that comes on the heels of our separation New York@Night last summer from the AllAboutJazz.com website. To emphasize that split, we felt 4 it was time to come out, as it were, with our own unique identity. So in that sense, a name is very important. But, echoing Shakespeare’s idea, the change in name Interview: Johnny Mandel will have no impact whatsoever on our continuing mission to explore new worlds 6 by Marcia Hillman and new civilizations...oh wait, wrong mission...to support the New York City and international jazz communities. If anything, the new name will afford us new Artist Feature: Elliott Sharp opportunities to accomplish that goal, whether it be in print or in a soon-to-be- 7 by Martin Longley expanded online presence. We are very excited for our next chapter and appreciate your continued interest and support. On The Cover: James Blood Ulmer But back to the business of jazz. -

The Avant-Garde in Jazz As Representative of Late 20Th Century American Art Music

THE AVANT-GARDE IN JAZZ AS REPRESENTATIVE OF LATE 20TH CENTURY AMERICAN ART MUSIC By LONGINEU PARSONS A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2017 © 2017 Longineu Parsons To all of these great musicians who opened artistic doors for us to walk through, enjoy and spread peace to the planet. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my professors at the University of Florida for their help and encouragement in this endeavor. An extra special thanks to my mentor through this process, Dr. Paul Richards, whose forward-thinking approach to music made this possible. Dr. James P. Sain introduced me to new ways to think about composition; Scott Wilson showed me other ways of understanding jazz pedagogy. I also thank my colleagues at Florida A&M University for their encouragement and support of this endeavor, especially Dr. Kawachi Clemons and Professor Lindsey Sarjeant. I am fortunate to be able to call you friends. I also acknowledge my friends, relatives and business partners who helped convince me that I wasn’t insane for going back to school at my age. Above all, I thank my wife Joanna for her unwavering support throughout this process. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .................................................................................................. 4 LIST OF EXAMPLES ...................................................................................................... 7 ABSTRACT -

Jazz at the Crossroads)

MUSIC 127A: 1959 (Jazz at the Crossroads) Professor Anthony Davis Rather than present a chronological account of the development of Jazz, this course will focus on the year 1959 in Jazz, a year of profound change in the music and in our society. In 1959, Jazz is at a crossroads with musicians searching for new directions after the innovations of the late 1940s’ Bebop. Musical figures such as Miles Davis and John Coltrane begin to forge a new direction in music building on their previous success earlier in the fifties. The recording Kind of Blue debuts in 1959 documenting the work of Miles Davis’ legendary sextet with John Coltrane, Cannonball Adderley, Bill Evans, Paul Chambers and Jimmy Cobb and reflects a new direction in the music with the introduction of a modal approach to composition and improvisation. John Coltrane records Giant Steps the culmination of the harmonic intricacies of Bebop and at the same time the beginning of something new. Ornette Coleman arrives in New York and records The Shape of Jazz to Come, an LP that presents a radical departure from the orthodoxies of Be-Bop. Dave Brubeck records Time Out, a record featuring a new approach to rhythmic structure in the music. Charles Mingus records Mingus Ah Um, establishing Mingus as a pre-eminent composer in Jazz. Bill Evans forms his trio with Scott LaFaro and Paul Motian transforming the interaction and function of the rhythm section. The quiet revolution in music reflects a world that is profoundly changed. The movement for Civil Rights has begun. The Birmingham boycott and the Supreme Court decision Brown vs. -

Pharoah Sanders Title: in the Beginning – 1963-1964 Label: Esp Disk 4069

CD REVIEW ARTIST: PHAROAH SANDERS TITLE: IN THE BEGINNING – 1963-1964 LABEL: ESP DISK 4069 TUNES: Disc 1: Interview (Sanders): Coming To New York Don Cherry Quintet : Cocktail Piece (first variation ) take 1 / Cocktail Piece (first variation ) take 2 / Cherry's Dilemma / Remembrance (first variation ) / Medley: Thelonious Monk compositions : Light Blue / Coming On The Hudson / Bye Ya / Ruby My Dear / Interview (Cherry): Ornette 's Influence Pts . 1 & 2. Paul Bley Quartet : Interview (Bley): 1960s Avant Garde / Generous 1 (take 1) / Generous 1 (take 2) / Walking Woman (take 1) / Walking Woman (take 2) / Ictus / After Session Conversation. Disc 2: Interview (Sanders): Musicians He's Performed With Pt. 1 / Interview (Stollman ) Meeting Pharoah Sanders. Pharoah Sanders Quintet : Seven By Seven / Bether A/ Interview (Sanders) Musicians He's Performed With Pt. 2 Disc 3: Interview (Sanders): Meeting Sun Ra Sun Ra And His Solar Arkestra : Dawn Over Israel / The Shadow World / The Second Stop Is Jupiter / Discipline #9 / We Travel The Spaceways. Disc 4: Interview (Sun Ra): Being Neglected As An Artist Sun Ra And HIs Solar Arkestra : Gods On Safari / The Shadow World / Rocket #9 / The Voice Of Pan Pt. 1 / Dawn Over Israel / Space Mates / The Voice Of Pan Pt. 2 / The Talking Drum / Conversation With Saturn / Pathway To The Outer Known . Interview (Ra) : Meeting John Coltrane / Interview (Sanders): John Coltrane / Interview (Sanders): Playing At Slug 's - Max Gordon / Interview (Sanders): Closing Comments total time (all 4 discs) 218:16. PERSONNEL: (disc 1?) Pharoah Sanders - ts; Don Cherry - tpt; Joe Scianni - p; David Izenzon - b; J.C. Moses - d. 1/3/63, New York City (disc 2) Pharoah Sanders - ts; Stan Foster - tpt; Jane Getz - p; William Bennett - b; Marvin Patillo - d. -

Recorded Jazz in the 20Th Century

Recorded Jazz in the 20th Century: A (Haphazard and Woefully Incomplete) Consumer Guide by Tom Hull Copyright © 2016 Tom Hull - 2 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................................1 Individuals..................................................................................................................................................2 Groups....................................................................................................................................................121 Introduction - 1 Introduction write something here Work and Release Notes write some more here Acknowledgments Some of this is already written above: Robert Christgau, Chuck Eddy, Rob Harvilla, Michael Tatum. Add a blanket thanks to all of the many publicists and musicians who sent me CDs. End with Laura Tillem, of course. Individuals - 2 Individuals Ahmed Abdul-Malik Ahmed Abdul-Malik: Jazz Sahara (1958, OJC) Originally Sam Gill, an American but with roots in Sudan, he played bass with Monk but mostly plays oud on this date. Middle-eastern rhythm and tone, topped with the irrepressible Johnny Griffin on tenor sax. An interesting piece of hybrid music. [+] John Abercrombie John Abercrombie: Animato (1989, ECM -90) Mild mannered guitar record, with Vince Mendoza writing most of the pieces and playing synthesizer, while Jon Christensen adds some percussion. [+] John Abercrombie/Jarek Smietana: Speak Easy (1999, PAO) Smietana -

Dypdykk I Musikkhistorien - Del 25: Sun Ra (16.09.2019 - TFB) Oppdatert 16.09.2019

Dypdykk i musikkhistorien - Del 25: Sun Ra (16.09.2019 - TFB) Oppdatert 16.09.2019 Spilleliste pluss noen ekstra lyttetips: Intro Enlightment (Nuits De La Fondation Maeght Volume 1 (1970) / Sun Ra) Inspirasjon Fletcher Henderson Anitras dance [1939] / The John Kirby Sextet (The eternal myth revealed vol. 1 : 1926-1959 (2011) [14 CD-box] / Sun Ra) Drums of passion (1959) / Olatunji! Tidlige år / Arrangør / R&B Doo wop / Singler Jitterbuggin [1948] / The Red Saunders Orchestra Smile [1949] / Sun Ra You go to my head [1949] / The Sonny Blunt Trio Call my baby [1953] / Jo Jo Adams w/ The Red Saunders Orchestra The best things in life are free [1953] / Sun Ra Velvet [1956] / The Sun Ra Bebop Band (The eternal myth revealed vol. 1 : 1926-1959 (2011) [14 CD-box] / Sun Ra) I am a instrument ; I am strange [195?] / Sun Ra Spaceship lullaby ; A foggy day / The Nu Sounds (Singles : the definitive 45s collection 1952-1991 (2016) / Sun Ra) Daddy’s gonna tell you no lie ; Bye bye / The Cosmic Rays (Singles : the definitive 45s collection 1952-1991 (2016) / Sun Ra) M uck m uck (Matt matt) ; Hot skillet momma (Singel, 1957) / Yochanan 1 Arkestra Jazz by Sun Ra (1957) Høyt tempo Enlightenment ; Ancient aiethopia (Jazz in silhouette [1958](1959) / Sun Ra and his Arkestra) Diverse Music from tomorrows world [1960](2002) / Sun Ra and his Arkestra The invisible shield [1961-1963, 1970] (1974) / Sun Ra and his Intergalactic Research Arkestra Cluster of galaxies ; Infinity of the universe ; Solar drums (Art forms of dimensions tomorrow [1961-62] / Sun Ra and his Solar Arkestra) Brazilian sun (When sun comes out (1963) / Sun Ra and his Myth Science Arkestra) Adventure equation ; Moon dance ; Thither and Yon (Cosmic tones for mental therapy [1963](1967) / Sun Ra and his Myth Science Arkestra) Atlantis ; Mu ; Yucatan #1 [Hohner clavinet] (Atlantis [1967-1968](1969) / Sun Ra and his Astro-Infinity Arkestra) The perfect man (My brother the wind vol.