Viscosity of Gas Mixtures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glossary Physics (I-Introduction)

1 Glossary Physics (I-introduction) - Efficiency: The percent of the work put into a machine that is converted into useful work output; = work done / energy used [-]. = eta In machines: The work output of any machine cannot exceed the work input (<=100%); in an ideal machine, where no energy is transformed into heat: work(input) = work(output), =100%. Energy: The property of a system that enables it to do work. Conservation o. E.: Energy cannot be created or destroyed; it may be transformed from one form into another, but the total amount of energy never changes. Equilibrium: The state of an object when not acted upon by a net force or net torque; an object in equilibrium may be at rest or moving at uniform velocity - not accelerating. Mechanical E.: The state of an object or system of objects for which any impressed forces cancels to zero and no acceleration occurs. Dynamic E.: Object is moving without experiencing acceleration. Static E.: Object is at rest.F Force: The influence that can cause an object to be accelerated or retarded; is always in the direction of the net force, hence a vector quantity; the four elementary forces are: Electromagnetic F.: Is an attraction or repulsion G, gravit. const.6.672E-11[Nm2/kg2] between electric charges: d, distance [m] 2 2 2 2 F = 1/(40) (q1q2/d ) [(CC/m )(Nm /C )] = [N] m,M, mass [kg] Gravitational F.: Is a mutual attraction between all masses: q, charge [As] [C] 2 2 2 2 F = GmM/d [Nm /kg kg 1/m ] = [N] 0, dielectric constant Strong F.: (nuclear force) Acts within the nuclei of atoms: 8.854E-12 [C2/Nm2] [F/m] 2 2 2 2 2 F = 1/(40) (e /d ) [(CC/m )(Nm /C )] = [N] , 3.14 [-] Weak F.: Manifests itself in special reactions among elementary e, 1.60210 E-19 [As] [C] particles, such as the reaction that occur in radioactive decay. -

Viscosity of Gases References

VISCOSITY OF GASES Marcia L. Huber and Allan H. Harvey The following table gives the viscosity of some common gases generally less than 2% . Uncertainties for the viscosities of gases in as a function of temperature . Unless otherwise noted, the viscosity this table are generally less than 3%; uncertainty information on values refer to a pressure of 100 kPa (1 bar) . The notation P = 0 specific fluids can be found in the references . Viscosity is given in indicates that the low-pressure limiting value is given . The dif- units of μPa s; note that 1 μPa s = 10–5 poise . Substances are listed ference between the viscosity at 100 kPa and the limiting value is in the modified Hill order (see Introduction) . Viscosity in μPa s 100 K 200 K 300 K 400 K 500 K 600 K Ref. Air 7 .1 13 .3 18 .5 23 .1 27 .1 30 .8 1 Ar Argon (P = 0) 8 .1 15 .9 22 .7 28 .6 33 .9 38 .8 2, 3*, 4* BF3 Boron trifluoride 12 .3 17 .1 21 .7 26 .1 30 .2 5 ClH Hydrogen chloride 14 .6 19 .7 24 .3 5 F6S Sulfur hexafluoride (P = 0) 15 .3 19 .7 23 .8 27 .6 6 H2 Normal hydrogen (P = 0) 4 .1 6 .8 8 .9 10 .9 12 .8 14 .5 3*, 7 D2 Deuterium (P = 0) 5 .9 9 .6 12 .6 15 .4 17 .9 20 .3 8 H2O Water (P = 0) 9 .8 13 .4 17 .3 21 .4 9 D2O Deuterium oxide (P = 0) 10 .2 13 .7 17 .8 22 .0 10 H2S Hydrogen sulfide 12 .5 16 .9 21 .2 25 .4 11 H3N Ammonia 10 .2 14 .0 17 .9 21 .7 12 He Helium (P = 0) 9 .6 15 .1 19 .9 24 .3 28 .3 32 .2 13 Kr Krypton (P = 0) 17 .4 25 .5 32 .9 39 .6 45 .8 14 NO Nitric oxide 13 .8 19 .2 23 .8 28 .0 31 .9 5 N2 Nitrogen 7 .0 12 .9 17 .9 22 .2 26 .1 29 .6 1, 15* N2O Nitrous -

On Nonlinear Strain Theory for a Viscoelastic Material Model and Its Implications for Calving of Ice Shelves

Journal of Glaciology (2019), 65(250) 212–224 doi: 10.1017/jog.2018.107 © The Author(s) 2019. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is unaltered and is properly cited. The written permission of Cambridge University Press must be obtained for commercial re- use or in order to create a derivative work. On nonlinear strain theory for a viscoelastic material model and its implications for calving of ice shelves JULIA CHRISTMANN,1,2 RALF MÜLLER,2 ANGELIKA HUMBERT1,3 1Division of Geosciences/Glaciology, Alfred Wegener Institute Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research, Bremerhaven, Germany 2Institute of Applied Mechanics, University of Kaiserslautern, Kaiserslautern, Germany 3Division of Geosciences, University of Bremen, Bremen, Germany Correspondence: Julia Christmann <[email protected]> ABSTRACT. In the current ice-sheet models calving of ice shelves is based on phenomenological approaches. To obtain physics-based calving criteria, a viscoelastic Maxwell model is required account- ing for short-term elastic and long-term viscous deformation. On timescales of months to years between calving events, as well as on long timescales with several subsequent iceberg break-offs, deformations are no longer small and linearized strain measures cannot be used. We present a finite deformation framework of viscoelasticity and extend this model by a nonlinear Glen-type viscosity. A finite element implementation is used to compute stress and strain states in the vicinity of the ice-shelf calving front. -

Guide to Rheological Nomenclature: Measurements in Ceramic Particulate Systems

NfST Nisr National institute of Standards and Technology Technology Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce NIST Special Publication 946 Guide to Rheological Nomenclature: Measurements in Ceramic Particulate Systems Vincent A. Hackley and Chiara F. Ferraris rhe National Institute of Standards and Technology was established in 1988 by Congress to "assist industry in the development of technology . needed to improve product quality, to modernize manufacturing processes, to ensure product reliability . and to facilitate rapid commercialization ... of products based on new scientific discoveries." NIST, originally founded as the National Bureau of Standards in 1901, works to strengthen U.S. industry's competitiveness; advance science and engineering; and improve public health, safety, and the environment. One of the agency's basic functions is to develop, maintain, and retain custody of the national standards of measurement, and provide the means and methods for comparing standards used in science, engineering, manufacturing, commerce, industry, and education with the standards adopted or recognized by the Federal Government. As an agency of the U.S. Commerce Department's Technology Administration, NIST conducts basic and applied research in the physical sciences and engineering, and develops measurement techniques, test methods, standards, and related services. The Institute does generic and precompetitive work on new and advanced technologies. NIST's research facilities are located at Gaithersburg, MD 20899, and at Boulder, CO 80303. -

Application Note to the Field Pumping Non-Newtonian Fluids with Liquiflo Gear Pumps

Pumping Non-Newtonian Fluids Application Note to the Field with Liquiflo Gear Pumps Application Note Number: 0104-2 Date: April 10, 2001; Revised Jan. 2016 Newtonian vs. non-Newtonian Fluids: Fluids fall into one of two categories: Newtonian or non-Newtonian. A Newtonian fluid has a constant viscosity at a particular temperature and pressure and is independent of shear rate. A non-Newtonian fluid has viscosity that varies with shear rate. The apparent viscosity is a measure of the resistance to flow of a non-Newtonian fluid at a given temperature, pressure and shear rate. Newton’s Law states that shear stress () is equal the dynamic viscosity () multiplied by the shear rate (): = . A fluid which obeys this relationship, where is constant, is called a Newtonian fluid. Therefore, for a Newtonian fluid, shear stress is directly proportional to shear rate. If however, varies as a function of shear rate, the fluid is non-Newtonian. In the SI system, the unit of shear stress is pascals (Pa = N/m2), the unit of shear rate is hertz or reciprocal seconds (Hz = 1/s), and the unit of dynamic viscosity is pascal-seconds (Pa-s). In the cgs system, the unit of shear stress is dynes per square centimeter (dyn/cm2), the unit of shear rate is again hertz or reciprocal seconds, and the unit of dynamic viscosity is poises (P = dyn-s-cm-2). To convert the viscosity units from one system to another, the following relationship is used: 1 cP = 1 mPa-s. Pump shaft speed is normally measured in RPM (rev/min). -

Investigations of Liquid Steel Viscosity and Its Impact As the Initial Parameter on Modeling of the Steel Flow Through the Tundish

materials Article Investigations of Liquid Steel Viscosity and Its Impact as the Initial Parameter on Modeling of the Steel Flow through the Tundish Marta Sl˛ezak´ 1,* and Marek Warzecha 2 1 Department of Ferrous Metallurgy, Faculty of Metals Engineering and Industrial Computer Science, AGH University of Science and Technology, Al. Mickiewicza 30, 30-059 Kraków, Poland 2 Department of Metallurgy and Metal Technology, Faculty of Production Engineering and Materials Technology, Cz˛estochowaUniversity of Technology, Al. Armii Krajowej 19, 42-201 Cz˛estochowa,Poland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 14 September 2020; Accepted: 5 November 2020; Published: 7 November 2020 Abstract: The paper presents research carried out to experimentally determine the dynamic viscosity of selected iron solutions. A high temperature rheometer with an air bearing was used for the tests, and ANSYS Fluent commercial software was used for numerical simulations. The experimental results obtained are, on average, lower by half than the values of the dynamic viscosity coefficient of liquid steel adopted during fluid flow modeling. Numerical simulations were carried out, taking into account the viscosity standard adopted for most numerical calculations and the average value of the obtained experimental dynamic viscosity of the analyzed iron solutions. Both qualitative and quantitative analysis showed differences in the flow structure of liquid steel in the tundish, in particular in the predicted values and the velocity profile distribution. However, these differences are not significant. In addition, the work analyzed two different rheological models—including one of our own—to describe the dynamic viscosity of liquid steel, so that in the future, the experimental stage could be replaced by calculating the value of the dynamic viscosity coefficient of liquid steel using one equation. -

Equation of Motion for Viscous Fluids

1 2.25 Equation of Motion for Viscous Fluids Ain A. Sonin Department of Mechanical Engineering Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 2001 (8th edition) Contents 1. Surface Stress …………………………………………………………. 2 2. The Stress Tensor ……………………………………………………… 3 3. Symmetry of the Stress Tensor …………………………………………8 4. Equation of Motion in terms of the Stress Tensor ………………………11 5. Stress Tensor for Newtonian Fluids …………………………………… 13 The shear stresses and ordinary viscosity …………………………. 14 The normal stresses ……………………………………………….. 15 General form of the stress tensor; the second viscosity …………… 20 6. The Navier-Stokes Equation …………………………………………… 25 7. Boundary Conditions ………………………………………………….. 26 Appendix A: Viscous Flow Equations in Cylindrical Coordinates ………… 28 ã Ain A. Sonin 2001 2 1 Surface Stress So far we have been dealing with quantities like density and velocity, which at a given instant have specific values at every point in the fluid or other continuously distributed material. The density (rv ,t) is a scalar field in the sense that it has a scalar value at every point, while the velocity v (rv ,t) is a vector field, since it has a direction as well as a magnitude at every point. Fig. 1: A surface element at a point in a continuum. The surface stress is a more complicated type of quantity. The reason for this is that one cannot talk of the stress at a point without first defining the particular surface through v that point on which the stress acts. A small fluid surface element centered at the point r is defined by its area A (the prefix indicates an infinitesimal quantity) and by its outward v v unit normal vector n . -

LII. the Viscosity of Gases and Molecular Force

Philosophical Magazine Series 5 ISSN: 1941-5982 (Print) 1941-5990 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tphm16 LII. The viscosity of gases and molecular force William Sutherland To cite this article: William Sutherland (1893) LII. The viscosity of gases and molecular force , Philosophical Magazine Series 5, 36:223, 507-531, DOI: 10.1080/14786449308620508 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14786449308620508 Published online: 08 May 2009. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 456 View related articles Citing articles: 13 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tphm16 Download by: [171.66.208.134] Date: 26 October 2015, At: 15:04 The Viscosity of Gases and Molecular Force. 507 likewise depends upon the ratio between the diameter anti length. 5th. That there are two maxima: one produced by increasing the current, another by decreasing the current fi'om tha~ point which produced the first maximum. 6th. They confirm Prof. A. M. Mayer's observations, tha~ the first contact gives more expansion than the second and following contacts~ and~ further, even these seem to disagree slightly among themselves~ the expansion falling off with subsequent contacts. Fig. 4. l * & $ ~ t" G "~ ! In fig. 4: I have plotted the expansion-curves of three of the bars which show tile greatest differences. hit. Bidwell's curves are similar in form to those produced by bars I. and II., while M. Alfonse Bergct's cm've, as would be cxpccted~ agrees more closely in form with that of bar V. -

Dynamic Viscosity, Surface Tension and Wetting Behavior Studies of Paraffin–In–Water † Nano–Emulsions

energies Article Dynamic Viscosity, Surface Tension and Wetting Behavior Studies of Paraffin–in–Water y Nano–Emulsions David Cabaleiro 1,2,3,* , Samah Hamze 1, Filippo Agresti 4 , Patrice Estellé 1,* , Simona Barison 4, Laura Fedele 2 and Sergio Bobbo 2 1 Université Rennes 1, LGCGM, EA3913, F-35704 Rennes, France 2 Institute of Construction Technologies, National Research Council, I–35127 Padova, Italy 3 Departamento de Física Aplicada, Universidade de Vigo, E–36310 Vigo, Spain 4 Institute of Condensed Matter Chemistry and Technologies for Energy, National Research Council, I–35127 Padova, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected] (D.C.); [email protected] (P.E.); Tel.: +33-(0)23234200 (P.E.) This article is an extended version of our paper published in 1st International Conference on Nanofluids y (ICNf) and 2nd European Symposium on Nanofluids (ESNf), Castellón, Spain, 26–28 June 2019; pp. 118–121. Received: 23 July 2019; Accepted: 24 August 2019; Published: 29 August 2019 Abstract: This work analyzes the dynamic viscosity, surface tension and wetting behavior of phase change material nano–emulsions (PCMEs) formulated at dispersed phase concentrations of 2, 4 and 10 wt.%. Paraffin–in–water samples were produced using a solvent–assisted route, starting from RT21HC technical grade paraffin with a nominal melting point at ~293–294 K. In order to evaluate the possible effect of paraffinic nucleating agents on those three properties, a nano–emulsion with 3.6% of RT21HC and 0.4% of RT55 (a paraffin wax with melting temperature at ~328 K) was also investigated. Dynamic viscosity strongly rose with increasing dispersed phase concentration, showing a maximum increase of 151% for the sample containing 10 wt.% of paraffin at 278 K. -

Non-Newtonian Fluids Flow Characteristic of Non-Newtonian Fluid

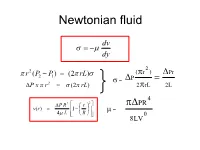

Newtonian fluid dv dy 2 r 2 (P P ) (2 rL) (r ) Pr 2 1 P 2 = P x r (2 rL) 2 rL 2L 2 4 P R2 r PR v(r) 1 4 L R = 8LV0 Definition of a Newtonian Fluid F du yx yx A dy For Newtonian behaviour (1) is proportional to and a plot passes through the origin; and (2) by definition the constant of proportionality, Newtonian dv dy 2 r 2 (P P ) (2 rL) (r ) Pr 2 1 P 2 = P x r (2 rL) 2 rL 2L 2 4 P R2 r PR v(r) 1 4 L R = 8LV0 Newtonian 2 From (r ) Pr d u = P 2rL 2L d y 4 and PR 8LQ = 0 4 8LV P = R = 8v/D 5 6 Non-Newtonian Fluids Flow Characteristic of Non-Newtonian Fluid • Fluids in which shear stress is not directly proportional to deformation rate are non-Newtonian flow: toothpaste and Lucite paint (Casson Plastic) (Bingham Plastic) Viscosity changes with shear rate. Apparent viscosity (a or ) is always defined by the relationship between shear stress and shear rate. Model Fitting - Shear Stress vs. Shear Rate Summary of Viscosity Models Newtonian n ( n 1) Pseudoplastic K n Dilatant K ( n 1) n Bingham y 1 1 1 1 Casson 2 2 2 2 0 c Herschel-Bulkley n y K or = shear stress, º = shear rate, a or = apparent viscosity m or K or K'= consistency index, n or n'= flow behavior index Herschel-Bulkley model (Herschel and Bulkley , 1926) n du m 0 dy Values of coefficients in Herschel-Bulkley fluid model Fluid m n Typical examples 0 Herschel-Bulkley >0 0<n< >0 Minced fish paste, raisin paste Newtonian >0 1 0 Water,fruit juice, honey, milk, vegetable oil Shear-thinning >0 0<n<1 0 Applesauce, banana puree, orange (pseudoplastic) juice concentrate Shear-thickening >0 1<n< 0 Some types of honey, 40 % raw corn starch solution Bingham Plastic >0 1 >0 Toothpaste, tomato paste Non-Newtonian Fluid Behaviour The flow curve (shear stress vs. -

Hydrostatic Fluid Hydrostatic Fluid/Anti-Wear Hydraulic Oil ISO 46 MV

Hydraulic Oils Hydrostatic Fluid Hydrostatic Fluid/Anti-Wear Hydraulic Oil ISO 46 MV General Description Hydrostatic Fluid is an exceptional quality hydrostatic and anti-wear ISO 46 multi-viscosity hydraulic oil containing additional additives to prevent wear. It is designed to exceed the performance requirements of many major hydrostatic and hydraulic pump manufacturers. Hydrostatic Fluid is specially formulated with the highest quality HCG-2 base oils that provide outstanding stability. The fluid is built with a uniquely balanced additive system to provide total anti-wear, anti-rust and complete oxidation, thermal and hydrolytic stability. Additionally, the additive package contains a demulsifying component, which allows any water to be eliminated from the oil. The added anti-wear agent used in Hydrostatic Fluid helps minimize wear in high speed, high pressure vane, gear, and piston pumps using various metallurgy while meeting the lubrication requirements of hydrostatic pumps and drives. Hydrostatic Fluid is a multi-viscosity oil formulated with an extremely shear stable viscosity modifier. It provides exceptional low temperature properties enabling performance over a wide range of startup and operating temperatures. Features and Benefits Oxidation Control: Excellent oxidation and Foam Control: A special anti-foam agent thermal stability reduces sludge and varnish promotes the rapid break up of foam and providing protection of critical components reduces air entrainment. while extending oil and equipment life. High Viscosity Index: The shear stability of Wear Protection: The premium anti-wear Hydrostatic Fluid 46 MV provides exceptional technology provides exceptional film viscosity stability, resulting in consistent strength resulting in longer pump life. operation throughout wide temperature ranges and drain intervals. -

4 Pressure and Viscosity

4 Pressure and Viscosity Reading: Ryden, chapter 2; Shu, chapter 4 4.1 Specific heats and the adiabatic index First law of thermodynamics (energy conservation): d = −P dV + dq =) dq = d + P dV; (28) − V ≡ ρ 1 = specific volume [ cm3 g−1] dq ≡ T ds = heat change per unit mass [ erg g−1] − s ≡ specific entropy [ erg g−1 K 1]: The specific heat at constant volume, @q −1 −1 cV ≡ [ erg g K ] (29) @T V is the amount of heat that must be added to raise temperature of 1 g of gas by 1 K. At constant volume, dq = d, and if depends only on temperature (not density), (V; T ) = (T ), then @q @ d cV ≡ = = : @T V @T V dT implying dq = cV dT + P dV: 1 If a gas has temperature T , then each degree of freedom that can be excited has energy 2 kT . (This is the equipartition theorem of classical statistical mechanics.) The pressure 1 ρ P = ρhjw~j2i = kT 3 m since 1 1 3kT h mw2i = kT =) hjw~j2i = : 2 i 2 m Therefore kT k P V = =) P dV = dT: m m Using dq = cV dT + P dV , the specific heat at constant pressure is @q dV k cP ≡ = cV + P = cV + : @T P dT m Changing the temperature at constant pressure requires more heat than at constant volume because some of the energy goes into P dV work. 19 For reasons that will soon become evident, the quantity γ ≡ cP =cV is called the adiabatic index. A monatomic gas has 3 degrees of freedom (translation), so 3 kT 3 k 5 k 5 = =) c = =) c = =) γ = : 2 m V 2 m P 2 m 3 A diatomic gas has 2 additional degrees of freedom (rotation), so cV = 5k=2m, γ = 7=5.