Chinese Language Policy in Singapore Author(S) Charlene Tan Source Language Policy, 5(1), 41-62

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Opening Remarks by Senior Minister Teo Chee Hean at the Public Sector Data Security Review Committee Press Conference on 27 November 2019

OPENING REMARKS BY SENIOR MINISTER TEO CHEE HEAN AT THE PUBLIC SECTOR DATA SECURITY REVIEW COMMITTEE PRESS CONFERENCE ON 27 NOVEMBER 2019 Good morning everyone and thank you for attending the press conference. Work of the PSDSRC 2 As you know, in 2018 and 2019, we uncovered a number of data-related incidents in the public sector. In response to these incidents, the government had immediately introduced additional IT security measures. Some of these measures included network traffic and database activity monitoring, and endpoint detection and response for all critical information infrastructure. But, there was a need for a more comprehensive look at public sector data security. 3 On 31 March this year, the Prime Minister directed that I chair a Committee to conduct a comprehensive review of data security policies and practices across the public sector. 4 I therefore convened a Committee, which consisted of my colleagues from government - Dr Vivian Balakrishnan, Mr S Iswaran, Mr Chan Chun Sing, and Dr Janil Puthucheary - as well as five international and private sector representatives with expertise in data security and technology. If I may just provide the background of these five private sector members: We have Professor Anthony Finkelstein, Chief Scientific Adviser for National Security to the UK Government and an expert in the area of data and cyber security; We have Mr David Gledhill who is with us today. He is the former Chief Information Officer of DBS and has a lot of experience in applying these measures in the financial and banking sector; We have Mr Ho Wah Lee, a former KPMG partner with 30 years of experience in information security, auditing and related issues across a whole range of entities in the private and public sector; We have Mr Lee Fook Sun, who is the Executive Chairman of Ensign Infosecurity. -

Conditionals in Political Texts

JOSIP JURAJ STROSSMAYER UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES Adnan Bujak Conditionals in political texts A corpus-based study Doctoral dissertation Advisor: Dr. Mario Brdar Osijek, 2014 CONTENTS Abstract ...........................................................................................................................3 List of tables ....................................................................................................................4 List of figures ..................................................................................................................5 List of charts....................................................................................................................6 Abbreviations, Symbols and Font Styles ..........................................................................7 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................9 1.1. The subject matter .........................................................................................9 1.2. Dissertation structure .....................................................................................10 1.3. Rationale .......................................................................................................11 1.4. Research questions ........................................................................................12 2. Theoretical framework .................................................................................................13 -

SECONDARY SCHOOL EDUCATION Shaping the Next Phase of Your Child’S Learning Journey 01 SINGAPORE’S EDUCATION SYSTEM : an OVERVIEW

SECONDARY SCHOOL EDUCATION Shaping the Next Phase of Your Child’s Learning Journey 01 SINGAPORE’S EDUCATION SYSTEM : AN OVERVIEW 03 LEARNING TAILORED TO DIFFERENT ABILITIES 04 EXPANDING YOUR CHILD’S DEVELOPMENT 06 MAXIMISING YOUR CHILD’S POTENTIAL 10 CATERING TO INTERESTS AND ALL-ROUNDEDNESS 21 EDUSAVE SCHOLARSHIPS & AWARDS AND FINANCIAL ASSISTANCE SCHEMES 23 CHOOSING A SECONDARY SCHOOL 24 SECONDARY 1 POSTING 27 CHOOSING A SCHOOL : PRINCIPALS’ PERSPECTIVES The Ministry of Education formulates and implements policies on education structure, curriculum, pedagogy and assessment. We oversee the development and management of Government-funded schools, the Institute of Technical Education, polytechnics and autonomous universities. We also fund academic research. SECONDARY SCHOOL 01 EDUCATION 02 Our education system offers many choices Singapore’s Education System : An Overview for the next phase of learning for your child. Its diverse education pathways aim to develop each child to his full potential. PRIMARY SECONDARY POST-SECONDARY WORK 6 years 4-5 years 1-6 years ALTERNATIVE SPECIAL EDUCATION SCHOOLS QUALIFICATIONS*** Different Pathways to Work and Life INTEGRATED PROGRAMME 4-6 Years ALTERNATIVE UNIVERSITIES QUALIFICATIONS*** SPECIALISED INDEPENDENT SCHOOLS** 4-6 Years WORK PRIVATELY FUNDED SCHOOLS SPECIAL 4-6 Years EDUCATION PRIMARY SCHOOL LEAVING EXPRESS GCE O-LEVEL JUNIOR COLLEGES/ GCE A-LEVEL CONTINUING EDUCATION EXAMINATION (PSLE) 4 Years CENTRALISED AND TRAINING (CET)**** INSTITUTE 2-3 Years Specialised Schools offer customised programmes -

Institutionalized Leadership: Resilient Hegemonic Party Autocracy in Singapore

Institutionalized Leadership: Resilient Hegemonic Party Autocracy in Singapore By Netina Tan PhD Candidate Political Science Department University of British Columbia Paper prepared for presentation at CPSA Conference, 28 May 2009 Ottawa, Ontario Work- in-progress, please do not cite without author’s permission. All comments welcomed, please contact author at [email protected] Abstract In the age of democracy, the resilience of Singapore’s hegemonic party autocracy is puzzling. The People’s Action Party (PAP) has defied the “third wave”, withstood economic crises and ruled uninterrupted for more than five decades. Will the PAP remain a deviant case and survive the passing of its founding leader, Lee Kuan Yew? Building on an emerging scholarship on electoral authoritarianism and the concept of institutionalization, this paper argues that the resilience of hegemonic party autocracy depends more on institutions than coercion, charisma or ideological commitment. Institutionalized parties in electoral autocracies have a greater chance of survival, just like those in electoral democracies. With an institutionalized leadership succession system to ensure self-renewal and elite cohesion, this paper contends that PAP will continue to rule Singapore in the post-Lee era. 2 “All parties must institutionalize to a certain extent in order to survive” Angelo Panebianco (1988, 54) Introduction In the age of democracy, the resilience of Singapore’s hegemonic party regime1 is puzzling (Haas 1999). A small island with less than 4.6 million population, Singapore is the wealthiest non-oil producing country in the world that is not a democracy.2 Despite its affluence and ideal socio- economic prerequisites for democracy, the country has been under the rule of one party, the People’s Action Party (PAP) for the last five decades. -

Singapore and Malaysia Agree to Strengthen Existing Bilateral Defence Relationship

Singapore and Malaysia Agree to Strengthen Existing Bilateral Defence Relationship 03 Jun 2018 Minister for Defence Dr Ng Eng Hen meeting with newly-appointed Malaysian Minister of Defence Mohamad Sabu on the sidelines of the 17th Shangri-La Dialogue. Minister for Defence Dr Ng Eng Hen met newly-appointed Malaysian Minister of Defence Mohamad Sabu on the sidelines of the 17th Shangri-La Dialogue (SLD) today, in their first official meeting. This is Mr Mohamad's inaugural visit to Singapore as the Malaysian Minister of Defence. 1 During their meeting, Dr Ng and Mr Mohamad affirmed the warm and long-standing defence relations between Singapore and Malaysia. They noted the good progress made in bilateral defence relations, such as the recent conduct of a new bilateral exercise between the two Air Forces. In addition, Dr Ng and Mr Mohamad affirmed both countries' cooperation in various regional multilateral platforms, such as the ASEAN Defence Ministers' Meeting (ADMM) and the ADMM-Plus, and the Five Power Defence Arrangements (FPDA). They also discussed regional challenges such as the situation in the Rakhine State. Singapore and Malaysia's defence establishments interact regularly across a wide range of activities, which includes bilateral exercises, visits and exchanges, cross-attendance of courses, as well as multilateral activities. These regular interactions strengthen mutual understanding and professional ties among the personnel of both defence establishments, and underscore the warm and long-standing defence ties between both countries. Mr Mohamad is visiting Singapore from 1 to 3 June 2018 to attend the 17th SLD. As part of his visit, he also called on Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong and Deputy Prime Minister and Coordinating Minister for National Security Teo Chee Hean. -

Annex B (Pdf, 314.38KB)

ANNEX B CABINET AND OTHER OFFICE HOLDERS (1 May 2014 unless stated otherwise) MINISTRY MINISTER MINISTER OF STATE PARLIAMENTARY SECRETARIES PMO Prime Minister's Office Mr Lee Hsien Loong Mr Heng Chee How (Prime Minister) (Senior Minister of State) Mr Teo Chee Hean #@ Mr Sam Tan ^*# (Deputy Prime Minister and (Minister of State) Coordinating Minister for National Security and Minister for Home Affairs) Mr Tharman Shanmugaratnam #@ (Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Finance) Mr Lim Swee Say @ Mr S Iswaran # (Minister, PMO, Second Minister for Home Affairs and Second Minister for Trade and Industry) Ms Grace Fu Hai Yien #@ (Minister, PMO, Second Minister for Environment and Water Resources and Second Minister for Foreign Affairs) FOREIGN AFFAIRS, SECURITY AND DEFENCE Defence Dr Ng Eng Hen Dr Mohamad Maliki Bin Osman # (Minister of State) Mr Chan Chun Sing # (Second Minister) Foreign Affairs Mr K Shanmugam # Mr Masagos Zulkifli # (Senior Minister of State) Ms Grace Fu Hai Yien #@ (Second Minister) Home Affairs Mr Teo Chee Hean #@ Mr Masagos Zulkifli # (Deputy Prime Minister) (Senior Minister of State) Mr S Iswaran # (Second Minister) Law Mr K Shanmugam # Ms Indranee Rajah # (Senior Minister of State) ECONOMICS Trade and Industry Mr Lim Hng Kiang Mr Lee Yi Shyan # (Senior Minister of State) Mr S Iswaran #+ Mr Teo Ser Luck # (Second Minister) (Minister of State) Finance Mr Tharman Shanmugaratnam #@ Mrs Josephine Teo # (Deputy Prime Minister) (Senior Minister of State) Transport Mr Lui Tuck Yew Mrs Josephine Teo # A/P Muhammad Faishal bin -

Speech by Mr Tharman Shanmugaratnam, Minister for Education & Second Minister

Speech by Mr Tharman Shanmugaratnam, Minister for Education & Second Minister ... Page 1 of 3 Print this page SPEECH BY MR THARMAN SHANMUGARATNAM, MINISTER FOR EDUCATION & SECOND MINISTER FOR FINANCE, AT THE LAUNCH OF MALAY LANGUAGE MONTH 2006, ON SATURDAY, 1 JULY 2006, AT 3.00 PM, AT TAMPINES JUNIOR COLLEGE AUDITORIUM Mr Hawazi Daipi, Senior Parliamentary Secretary, Ministry of Manpower and Chairperson of the Malay Language Month 2006 Organising Committee, Members of Parliament, Distinguished Guests, Ladies and Gentlemen. (SPEECH DELIVERED IN MALAY) Introduction 1. It is my pleasure to be here to join you in launching the Malay Language Month 2006. 2. I am very pleased that a community event like this is held in a school. It provides a good opportunity for the community to have a better understanding of the changes that are happening in our schools, and for our students to have real-life community experience. 3. We need to create this kind of opportunity as often as possible, so as to establish a close school-community bond. Together, our schools and the community can work towards making the learning and use of the Mother Tongue Language, in your case, the Malay language, become meaningful to our students. Together, we can make Malay language lessons come alive for our Malay Language Elective Programme (MLEP) students in Tampines Junior College, applying the language in practical terms in and outside the school what they have learnt in class. This, of course, can be replicated in other schools. Staying Relevant and Current 4. Government is committed to keeping the teaching and learning of the Mother Tongue relevant and current to the needs of our students. -

Representations of the Name Rectification Movement of Taiwan Indigenous People: Through Whose Historical Lens?

LANGUAGE AND LINGUISTICS 13.3:523-568, 2012 2012-0-013-003-000320-1 Representations of the Name Rectification Movement of Taiwan Indigenous People: Through Whose Historical Lens? Sheng-hsiu Chiu1,2 and Wen-yu Chiang1 National Taiwan University1 Huafan University2 Within the theoretical and methodological framework based on the conceptual metaphor theory, the discourse-historical approach, and corpus linguistics, this article examines the various representations of Taiwan indigenous people’s name rectification movement in three major broadsheet newspapers, the United Daily News, the Liberty Times, and the Apple Daily in Taiwan. Using two-tier analysis, which incorporates the discourse-historical approach into the conceptual metaphor theory, we demonstrate that JOURNEY and CONFLICT metaphors, the two pre- dominant types identified in news coverage, are portrayed in divergent ways in different news media. By analyzing the cognitive characteristics of conceptual meta- phors in combination with other discursive/rhetorical strategies, we demonstrate that political orientations and underlying ideologies are ingrained in the corpora news reports, and the ways in which the newspapers’ publishers delineate the indigenous issue echo the different positions they take toward national identity. We hence posit that ‘Taiwan indigenous people as the positive Self’ construction is a pseudo-positive Self construction, which is merely a camouflage for the media’s real stance on viewing indigenous people as the Other. We argue that all of the representations of the name rectification movement in three different newspapers in Taiwan are based on intention, inextricably intertwined with the newspapers’ ideological stance of national identity, and are viewed through the historical lens of the Han people. -

UAE, Singapore Sign Comprehensive Partnership Agreements

UAE, Singapore sign comprehensive partnership agreements MoUs signed in the education, technology, and environment sectors, with the aim to benefit both countries interests. Singapore Skyscrapers Singapore Financial building at raffle place a central business district of Singapore with cloud Getty Images/ BNBB Studio By Staff Writer, WAM (Emirates News Agency) SINGAPORE - His Highness Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi and Deputy Supreme Commander of the UAE Armed Forces, and Lee Hsien Loong, Prime Minister of Singapore, witnessed the signing of a comprehensive partnership agreement between the UAE and Singapore, along with a number of memoranda of understanding, MoUs, in the education, technology, and environment sectors, with the aim to benefit both countries interests. Dr. Anwar bin Mohammed Gargash, Minister of State for Foreign Affairs, signed the comprehensive partnership agreement between the UAE and Singapore, alongside Dr. Mohammed Malki bin Othman, Senior Minister of State for Defence and Foreign Affairs. An agreement was signed between ADNOC and Nanyang Technological University, NTU Singapore, was signed by Dr. Sultan bin Ahmad Sultan Al Jaber, Minister of State and ADNOC Group CEO, and Professor Alan Chan, Vice President (Alumni & Advancement) at NTU Singapore. Dr. Thani bin Ahmed Al Zeyoudi, Minister of Climate Change and Environment, and Masagos Zulkifli, Minister for the Environment and Water Resources, signed an MoU on the protection of the environment. As for green projects development and applying best practices, Khaldoon Khalifa Al Mubarak, Chairman of Abu Dhabi Executive Affairs Authority, and Dr Leong Chee Chiew, Deputy Chief Executive Officer and Commissioner of Parks & Recreation at the National Parks Board. -

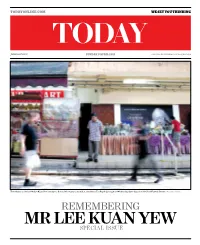

Lee Kuan Yew Continue to flow As Life Returns to Normal at a Market at Toa Payoh Lorong 8 on Wednesday, Three Days After the State Funeral Service

TODAYONLINE.COM WE SET YOU THINKING SUNDAY, 5 APRIL 2015 SPECIAL EDITION MCI (P) 088/09/2014 The tributes to the late Mr Lee Kuan Yew continue to flow as life returns to normal at a market at Toa Payoh Lorong 8 on Wednesday, three days after the State Funeral Service. PHOTO: WEE TECK HIAN REMEMBERING MR LEE KUAN YEW SPECIAL ISSUE 2 REMEMBERING LEE KUAN YEW Tribute cards for the late Mr Lee Kuan Yew by the PCF Sparkletots Preschool (Bukit Gombak Branch) teachers and students displayed at the Chua Chu Kang tribute centre. PHOTO: KOH MUI FONG COMMENTARY Where does Singapore go from here? died a few hours earlier, he said: “I am for some, more bearable. Servicemen the funeral of a loved one can tell you, CARL SKADIAN grieved beyond words at the passing of and other volunteers went about their the hardest part comes next, when the DEPUTY EDITOR Mr Lee Kuan Yew. I know that we all duties quietly, eiciently, even as oi- frenzy of activity that has kept the mind feel the same way.” cials worked to revise plans that had busy is over. I think the Prime Minister expected to be adjusted after their irst contact Alone, without the necessary and his past week, things have been, many Singaporeans to mourn the loss, with a grieving nation. fortifying distractions of a period of T how shall we say … diferent but even he must have been surprised Last Sunday, about 100,000 people mourning in the company of others, in Singapore. by just how many did. -

A Great Place To

Issue 34 April 2008 A newsletter of the Singapore Cooperation Programme experiencesingapore to Fly Place A Great • Singapore Fashion Festival Festival Fashion • Singapore • chartsASEAN anew [5] course boosts • ties [2] with India Singapore IN THIS ISSUE The new Terminal 3complex. The newTerminal a rising star [6] MAKING FRIENDS New Era of Singapore-Thai Ties “Singapore and Thailand are old friends. Outside Singapore’s old Parliament House stands a bronze elephant monument, which was presented to us by King Chulalongkorn during his historic visit in 1871, the first by a Thai monarch. This was the beginning of a friendship which has endured and grown stronger with the passage of time.” – PM Lee Hsien Loong, at a dinner honouring PM Samak Sundaravej BILATERAL ties between Singapore and Thailand Thailand’s Prime Minister Samak Sundaravej tours the Tiong Bahru Market during his official visit to Singapore. have entered a new era, following a meeting in Accompanying him are Mr Lee Yuen Hee, (third from left), CEO of NEA and Mr Lim Swee Say, (right, next to Mr Samak), Secretary-General of NTUC. March between the two countries’ leaders. Thai Prime Minister Samak Sundaravej, such as agriculture, life sciences, automotive met with Minister Mentor Lee Kuan Yew who is also Minister of Defence, met Singapore and financial services. and Defence Minister Teo Chee Hean. PM Lee Hsien Loong in Singapore as part of Singapore is one of Thailand’s top trading But it wasn’t all work no play for the Thai his introductory tour of the region after taking partners, with bilateral trade of more than PM, who used to host his own TV cooking office in February. -

The Interrupted Intercourse in the Election Communication: Pragmatic Aspect

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ENVIRONMENTAL & SCIENCE EDUCATION 2016, VOL. 11, NO. 11, 4040-4053 OPEN ACCESS The Interrupted Intercourse in the Election Communication: Pragmatic Aspect Olga K. Andryuchshenkoa, Gulnara S. Suyunovaa, Bibigul Dz. Nygmetovaa and Ekaterina P. Garaninaa aPavlodar State Pedagogical Institute, Pavlodar, KAZAKHSTAN ABSTRACT The article provides analysis of the interrupted communication as part of the communication in the election discourse. The authors explored the most typical reasons for the interrupted communication in the electoral discourse analyzed communication failures as a kind of ineffective communication. Communication failures are presented as a result of interrupted communication, which may be determined by several reasons. The paper disclosed the key reason of these failures - the intention of the speaker - the reluctance to continue the conversation for one reason or another. The communication failures in terms of the election discourse were typical largely for the election debate, characterized by the impossibility of predicting future responses, uncomfortable questions that often required non-standard speech decisions on the part of the speaker. The study established the relationship between the ability of a politician to maintain effective communication and the creation of his positive or negative political image. Psychological causes of interrupted speech present a separate group: the emotional state of the speaker, his perception or non- perception of the opponent, the ability to transfer the required