Online Appendix: Not for Publication the Competitive Impact of Vertical Integration by Multiproduct Firms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Keurig to Acquire Dr Pepper Snapple for $18.7Bn in Cash

Find our latest analyses and trade ideas on bsic.it Coffee and Soda: Keurig to acquire Dr Pepper Snapple for $18.7bn in cash Dr Pepper Snapple Group (NYSE:DPS) – market cap as of 17/02/2018: $28.78bn Introduction On January 29, 2018, Keurig Green Mountain, the coffee group owned by JAB Holding, announced the acquisition of soda maker Dr Pepper Snapple Group. Under the terms of the reverse takeover, Keurig will pay $103.75 per share in a special cash dividend to Dr Pepper shareholders, who will also retain 13 percent of the combined company. The deal will pay $18.7bn in cash to shareholders in total and create a massive beverage distribution network in the U.S. About Dr Pepper Snapple Group Incorporated in 2007 and headquartered in Plano (Texas), Dr Pepper Snapple Group, Inc. manufactures and distributes non-alcoholic beverages in the United States, Mexico and the Caribbean, and Canada. The company operates through three segments: Beverage Concentrates, Packaged Beverages, and Latin America Beverages. It offers flavored carbonated soft drinks (CSDs) and non-carbonated beverages (NCBs), including ready-to-drink teas, juices, juice drinks, mineral and coconut water, and mixers, as well as manufactures and sells Mott's apple sauces. The company sells its flavored CSD products primarily under the Dr Pepper, Canada Dry, Peñafiel, Squirt, 7UP, Crush, A&W, Sunkist soda, Schweppes, RC Cola, Big Red, Vernors, Venom, IBC, Diet Rite, and Sun Drop; and NCB products primarily under the Snapple, Hawaiian Punch, Mott's, FIJI, Clamato, Bai, Yoo- Hoo, Deja Blue, ReaLemon, AriZona tea, Vita Coco, BODYARMOR, Mr & Mrs T mixers, Nantucket Nectars, Garden Cocktail, Mistic, and Rose's brand names. -

Form 10-Q United States Securities and Exchange Commission Washington, D.C

FORM 10-Q UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 (Mark One) X QUARTERLY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the quarterly period ended March 20, 1999 (12 weeks) ------------------------------ OR TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission file number 1-1183 [GRAPHIC OMITTED] PEPSICO, INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) North Carolina 13-1584302 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporate or organization) Identification No.) 700 Anderson Hill Road, Purchase, New York 10577 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) 914-253-2000 (Registrant's telephone number, including area code) N/A (Former name, former address and former fiscal year, if changed since last report.) Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. YES X NO Number of shares of Capital Stock outstanding as of April 16, 1999: 1,476,995,019 PEPSICO, INC. AND SUBSIDIARIES INDEX Page No. Part I Financial Information Condensed Consolidated Statement of Income - 12 weeks ended March 20, 1999 and March 21, 1998 2 Condensed Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows - 12 weeks ended -

2017 Plains Region Portfolio 2017 Plains Region Portfolio Norfolk Division 2001 Riverside Blvd

2017 Plains Region Portfolio 2017 Plains Region Portfolio Norfolk Division 2001 Riverside Blvd. Norfolk, NE 68701 (402) 371-9347 or (866) 248-7645 Fax: (866) 592-3774 Mick Lusero Omaha Branch Manager [email protected] (402) 505-2634 Jonathan Grimm Brian Buresh Distribution Supervisor Warehouse Supervisor [email protected] [email protected] (402) 860-1472 (402) 860-0757 Rick Anderson Jennifer Risinger Vending Department Administrative Assistant [email protected] [email protected] (402) 616-5777 (402) 371-9347 Danny Olson Sales – Yankton/Wayne – Northern Region [email protected] (402) 649-6681 Scott Weinrich Sales – Norfolk/West Point – Central Region [email protected] (402) 750-5365 Randy Walnofer Sales – Columbus/Schuyler – Southern Region [email protected] (402) 992-9101 TO PLACE AN ORDER For equipment service: [email protected] [email protected] (800) 862-1904, option #2 (866) 592-3774, option #2 Please include your account number and business name Carbonated Soft Drinks 12oz Cans (2x12pk) Dr Pepper Dr Pepper TEN Diet Dr Pepper 1000 0836 Deposit 1000 1754 Deposit 1000 3730 1000 2434 No Deposit 1000 2435 No Deposit 0-78000-08216-6 0-78000-10316-8 0-78000-08316-3 Cherry Diet Cherry Dr Pepper Dr Pepper 1000 1749 1000 1750 0-78000-09816-7 0-78000-09916-4 Dr Pepper Diet Caffeine Free Made with Sugar Dr Pepper 1000 2778 1000 0835 0-78000-10216-1 0-78000-08516-7 Carbonated Soft Drinks 12oz Cans (2x12pk) 7Up 7Up TEN Diet 7Up 1000 0829 Deposit 1000 0830 Deposit 1002 0900 -

City Wide Wholesale Foods

City Wide Wholesale Foods City Wide Wholesale Foods WWW: http://www.citywidewholesale.com E-mail: [email protected] Phone: 713-862-2530 801 Service St Houston, TX. 77009 Sodas 24/20oz Classic Coke 24/20 Coke Zero 24/20 Cherry Coke 24/20 Vanilla Coke 24/20 Diet Coke 24/20 25.99 25.99 25.99 25.99 25.99 Sprite 24/20 Sprite Zero 24/20 Fanta Orange 24/20 Fanta Strawberry 24/20 Fanta Pineapple 24/20 25.99 25.99 22.99 22.99 22.99 Minute Maid Fruit Punch Minute Maid Pink Lemonade Pibb Xtra 24/20 Barqs Root Beer 24/20 Minute Maid Lemonade 24/20 24/20 24/20 22.99 22.99 22.99 22.99 22.99 Fuze Tea w/Lemon 24/20 Delaware Punch 24/20 Dr Pepper 24/20 Cherry Dr Pepper 24/20 Diet Cherry Dr Pepper 24/20 22.99 25.99 24.99 24.99 24.99 Diet Dr Pepper 24/20 Big Red 24/20 Big Blue 24/20 Big Peach 24/20 Big Pineapple 24/20 24.99 24.99 24.99 24.99 24.99 Sunkist Orange 24/20 Diet Sunkist Orange 24/20 Sunkist Grape 24/20oz Sunkist Strawberry 24/20oz 7-Up 24/20 21.99 21.99 21.99 21.99 21.99 Page 2/72 Sodas 24/20oz Diet 7-Up 24/20 Cherry 7-Up 24/20 Squirt 24/20 Hawaiian Punch 24/20 Tahitian Treat 24/20 21.99 21.99 21.99 21.99 21.99 RC Cola 24/20 Ginger Ale 24/20 A&W Root Beer 24/20 Diet A&W Root Beer 24/20 A&W Cream Soda 24/20 21.99 21.99 21.99 21.99 21.99 Pepsi Cola 24/20 Diet Pepsi 24/20 Lipton Brisk Tea 24/20 Lipton Green Tea 24/20 Manzanita Sol 24/20 23.99 23.99 23.99 23.99 23.99 Sodas 24/12oz Mountain Dew 24/20 Diet Mountain Dew 24/20 Classic Coke 2/12 Coke Zero 2/12 Cherry Coke 2/12 23.99 23.99 9.99 9.99 9.99 Vanilla Coke 2/12 Diet Coke 2/12 Sprite -

DR PEPPER SNAPPLE GROUP ANNUAL REPORT DPS at a Glance

DR PEPPER SNAPPLE GROUP ANNUAL REPORT DPS at a Glance NORTH AMERICA’S LEADING FLAVORED BEVERAGE COMPANY More than 50 brands of juices, teas and carbonated soft drinks with a heritage of more than 200 years NINE OF OUR 12 LEADING BRANDS ARE NO. 1 IN THEIR FLAVOR CATEGORIES Named Company of the Year in 2010 by Beverage World magazine CEO LARRY D. YOUNG NAMED 2010 BEVERAGE EXECUTIVE OF THE YEAR BY BEVERAGE INDUSTRY MAGAZINE OUR VISION: Be the Best Beverage Business in the Americas STOCK PRICE PERFORMANCE PRIMARY SOURCES & USES OF CASH VS. S&P 500 TWO-YEAR CUMULATIVE TOTAL ’09–’10 JAN ’10 MAR JUN SEP DEC ’10 $3.4B $3.3B 40% DPS Pepsi/Coke 30% Share Repurchases S&P Licensing Agreements 20% Dividends Net Repayment 10% of Credit Facility Operations & Notes 0% Capital Spending -10% SOURCES USES 2010 FINANCIAL SNAPSHOT (MILLIONS, EXCEPT EARNINGS PER SHARE) CONTENTS 2010 $5,636 NET SALES +2% 2009 $5,531 $ 1, 3 21 SEGMENT +1% Letter to Stockholders 1 OPERATING PROFIT $ 1, 310 Build Our Brands 4 $2.40 DILUTED EARNINGS +22% PER SHARE* $1.97 Grow Per Caps 7 Rapid Continuous Improvement 10 *2010 diluted earnings per share (EPS) excludes a loss on early extinguishment of debt and certain tax-related items, which totaled Innovation Spotlight 23 cents per share. 2009 diluted EPS excludes a net gain on certain 12 distribution agreement changes and tax-related items, which totaled 20 cents per share. See page 13 for a detailed reconciliation of the Stockholder Information 12 7 excluded items and the rationale for the exclusion. -

Tri R Coffee & Vending Product List

Tri R Coffee & Vending Product List Cold Beverages Pepsi Snapple Juice Snapple Diet Pepsi Max Snapple Tea Snapple Lemon Pepsi Natural Dasani Water Snapple Pink Lemonade Pepsi One SoBe Energize Mango Melon Lipton Brisk Strawberry Melon Pepsi Throwback SoBe Energize Power Fruit Punch Lipton Brisk Sugar Free Lemonade Caffeine Free Pepsi SoBe Lean Fuji Apple Cranberry Lipton Brisk Sugar Free Orangeade Diet Pepsi SoBe Lean Honey Green Tea Lipton Brisk Sweet Iced Tea Diet Pepsi Lime SoBe Lean Raspberry Lemonade Lipton Diet Green Tea with Citrus Diet Pepsi Vanilla SoBe Lifewater Acai Fruit Punch Lipton Diet Green Tea with Mixed Berry Diet Pepsi Wild Cherry SoBe Lifewater Agave Lemonade Lipton Diet Iced Tea with Lemon Caffeine Free Diet Pepsi SoBe Lifewater B-Energy Black Cherry Dragonfruit Lipton Diet White Tea with Raspberry Sierra Mist Natural SoBe Lifewater B-Energy Strawberry Apricot Lipton Green Tea with Citrus Diet Sierra Mist SoBe Lifewater Black and Blue Berry Lipton Iced Tea Lemonade Sierra Mist Cranberry Splash SoBe Lifewater Blackberry Grape Lipton Iced Tea with Lemon Diet Sierra Mist Cranberry Splash SoBe Lifewater Cherimoya Punch Lipton PureLeaf - Diet Lemon Diet Sierra Mist Ruby Splash SoBe Lifewater Fuji Apple Pear Lipton PureLeaf - Extra Sweet Ocean Spray Apple Juice SoBe Lifewater Macintosh Apple Cherry Lipton PureLeaf - Green Tea with Honey Ocean Spray Blueberry Juice Cocktail SoBe Lifewater Mango Melon Lipton PureLeaf - Lemon Ocean Spray Cranberry Juice Cocktail SoBe Lifewater Orange Tangerine Lipton PureLeaf - Peach Ocean -

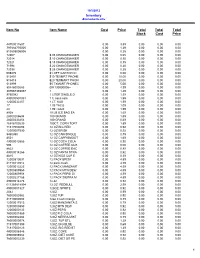

TX Convenient Database

10/5/2012 Inventory Alphabetically Item No Item Name Cost Price Total Total Total Stock Cost Price 44700011607 0.00 3.89 0.00 0.00 0.00 797884770005 0.00 1.29 0.00 0.00 0.00 813805005008 0.00 0.25 0.00 0.00 0.00 72007 $.05 CHANGEMAKER 0.00 0.05 0.00 0.00 0.00 72014 $.10 CHANGEMAKER 0.00 0.10 0.00 0.00 0.00 72021 $.15 CHANGEMAKER 0.00 0.15 0.00 0.00 0.00 71994 $.20 CHANGEMAKER 0.00 0.20 0.00 0.00 0.00 72038 $.25 CHANGEMAKER 0.00 0.25 0.00 0.00 0.00 609470 $1 OFF CARTON CI 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 513401 $10 TEXMRT PHONE 0.00 10.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 513418 $20 TEXMART PHON 0.00 20.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 513999 $5 TXMART PHONEC 0.00 5.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 90446000283 004130000006+ 0.00 4.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 307667393057 1 0.00 1.49 0.00 0.00 0.00 9750982 1 LITER SINGLE D 0.00 1.59 0.00 0.00 0.00 490000501031 1 lt. coca cola 0.00 1.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 12000032257 1 LT. KAS 0.00 1.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 17 1.09 TACO 0.00 1.09 0.00 0.00 0.00 24 1.99 TACO 0.00 1.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 8938 10 LB ICE BAG EA 0.00 1.69 0.00 0.00 0.00 28000206604 100 GRAND 0.00 1.59 0.00 0.00 0.00 28000333454 100 GRAND 0.00 0.69 0.00 0.00 0.00 16916100239 100CT. -

Exhibit Sales

Exhibit Sales are OPEN! Exhibit at InterBev for access to: • Beverage producers and distributors • Owners and CEOs • Sales/marketing professionals • Packaging and process engineers • Production, distribution and warehousing managers • R&D personnel Specialty Pavilions: • New Beverage Pavilion • Green Pavilion • Organic/Natural Pavilion NEW FOR 2012! “Where the beverage industry does business.” October 16-18, 2012 Owned & Operated by: Sands Expo & Convention Center Las Vegas, Nevada, USA Supported by: www.InterBev.com To learn more, email [email protected] or call 770.618.5884 Soft Drinks Internationa l – July 2012 ConTEnTS 1 news Europe 4 Africa 6 Middle East 8 India 10 The leading English language magazine published in Europe, devoted exclusively to the manufacture, distribution and marketing of soft drinks, fruit juices and bottled water. Asia Pacific 12 Americas 14 Ingredients 16 features Acerola, Baobab And Juices & Juice Drinks 18 Ginseng 28 Waters & Water Plus Drinks 20 Extracts from these plants offer beverage manufacturers the opportunity to enrich Carbonates 22 products in many ways, claims Oliver Sports & Energy 24 Hehn. Adult/Teas 26 Re-design 30 Packaging designed to ‘leave an impres - Packaging sion’ has contributed to impressive 38 growth, according to bottlegreen. Environment 40 People Closure Encounters 30 42 Rather than placing a generic screw top Events 43 onto a container at the very end of the design process, manufacturers need to begin with the closure, writes Peter McGeough. Adding Value To Bottled Water 34 From Silent Salesman 32 In the future, most volume growth in bot - Steve Osborne explores the marketing tled water will come from developing opportunities presented by multi-media markets, so past dynamics are likely to regulars technologies and how these might be continue. -

The 2017 Beverage Marketing Directory Copyright Notice

About this demo This demonstration copy of The Beverage Marketing Directory – PDF format is designed to provide an idea of the types and depth of information and features available to you in the full version as well as to give you a feel for navigating through The Directory in this electronic format. Be sure to visit the Features section and use the bookmarks to click through the various sections and of the PDF edition. What the PDF version offers: The PDF version of The Beverage Marketing Directory was designed to look like the traditional print volume, but offer greater electronic functionality. Among its features: · easy electronic navigation via linked bookmarks · the ability to search for a company · ability to visit company websites · send an e-mail by clicking on the link if one is provided Features and functionality are described in greater detail later in this demo. Before you purchase: Please note: The Beverage Marketing Directory in PDF format is NOT a database. You cannot manipulate or add to the information or download company records into spreadsheets, contact management systems or database programs. If you require a database, Beverage Marketing does offer them. Please see www.bmcdirectory.com where you can download a custom database in a format that meets your needs or contact Andrew Standardi at 800-332-6222 ext. 252 or 740-314-8380 ext. 252 for more information. For information on other Beverage Marketing products or services, see our website at www.beveragemarketing.com The 2017 Beverage Marketing Directory Copyright Notice: The information contained in this Directory was extensively researched, edited and verified. -

U.S. Brands Shopping List

Breakfast Bars/Granola Bars: Other: Snacks Con’t: Quaker Chewy Granola Bars Aunt Jemima Mixes & Syrups Rold Gold Pretzels Quaker Chewy Granola Cocoa Bars Quaker Oatmeal Pancake Mix Ruffles Potato Chips Quaker Chewy Smashbars Rice Snacks: Sabra hummus, dips and salsas Quaker Dipps Granola Bars Quaker Large Rice Cakes Sabritones Puffed Wheat Snacks Quaker Oatmeal to Go Bars Quaker Mini Delights Santitas Tortilla Chips Quaker Stila Bars Quaker Multigrain Fiber Crisps Smartfood Popcorn Coffee Drinks: Quaker Quakes Smartfood Popcorn Clusters Seattle’s Best Coffee Side Dishes: Spitz Seeds Starbucks DoubleShot Near East Side Dishes Stacy’s Pita and Bagel Chips Starbucks Frappuccino Pasta Roni Side Dishes SunChips Multigrain Snacks Starbucks Iced Coffee Rice‐A‐Roni Side Dishes Tostitos Artisan Recipes Tortilla Chips Energy Drinks: Snacks: Tostitos Multigrain Tortilla Chips U.S. Brands AMP Energy Baked! Cheetos Snacks Tostitos Tortilla Chips No Fear Energy Drinks Baked! Doritos Tortilla Chips Soft Drinks: Shopping List Starbucks Refreshers Baked! Lay’s Potato Crisps Citrus Blast Tea/Lemonade: Baked! Ruffles Potato Chips Diet Pepsi Brisk Baked! Tostitos Tortilla Chips Diet Mountain Dew Lipton Iced Tea Baken‐ets Pork Skins and Cracklins Diet Sierra Mist Lipton PureLeaf Cheetos Cheese Flavored Snacks Manzanita Sol SoBe Tea Chester’s Flavored Fries Mirinda Tazo Tea Chester’s Popcorn Mountain Dew Juice/Juice Drinks: Cracker Jack Candy Coated Popcorn Mug Soft Drinks AMP Energy Juice Doritos -

Freshest Produce Mug Root Beer, Diet Pepsi, Del Monte Folgers Fresh Iceberg from Mexico Large Mt

REGISTER FOR YOUR CHANCE TO Fresh Hot Fresh Pumpkin Pecan WIN OVER $4,000 IN PRIZES Menudo Buñuelos Pie Pie SPORTS CHAIRS Dinner Rolls Cheese Cake 3 Leches Cake YETI Jr’S GIFT B.B.Q. COOLERS CARDS DRAWING DATE 12-23-17 PITS Apple, Pecan, Pumpkin Pies Assorted Cakes, Large REGISTER AT ANY JUNIOR’s locaTION. SEE STORE FOR DETAILS. NO PURCHASE NECESSARY. EACH STORE WILL HAVE 4 WINNERS. Assorment of Dinner Rolls and Fresh Baked Bolillos SPECIALS GOOD NOV 15, THRU NOV 23, 2017 VENDORS, EMPLOYEES AND THEIR IMMEDIATE FAMILY NOT ELIGIBLE. OPEN OPEN Thanksgiving Day Thanksgiving Day 7am - 5pm Happy Thanksgiving 7am - 5pm Freshest Produce Mug Root Beer, Diet Pepsi, Del Monte Folgers Fresh Iceberg From Mexico Large Mt. Dew, Sierra Mist, Brisk, Maseca Cut Green Beans, Peas, (Asst. Varieties) Instant Flour or Mixed Vegetables Lettuce Hass Avocados Manzanita Sol or Corn Coffee Pepsi Cola Masa para Tamal $ $ 59 ¢ $ 5 13-15.253 oz. 624-30.5 oz. Ea. Ea. Kraft Imperial 99Fresh Roma 2U .S. #13 Mayo (Pure Cane) Tomato Russet Potato Sugar 5 Lb. Bag $ 99 $ 59 $ 99 $ 99 ¢ $ Lb. 12 Pk.-12 oz. 4.4 Lb. Bag 1 30 oz. 1 4 Lb. Ea. 3 9Sierra Mist, Brisk, Ozarka 2 Abuelita Riceland Parade Coffee Gold Medal Fresh Green F7resh 9 Fresh Yams Fresh 2 Fresh3 Large Diet Pepsi, Mt. Dew, Onion Cranberries 100% Authentic Long Vegetable Mate (All Purpose) Bulk Beets 1 Lb. Bag Celery Stalk Manzanita Sol or Spring Chocolate Grain Oil Creamer Flour Pepsi Cola Water Rice $ ¢ ¢ $ 99 $ 09 ¢ $ 99 $ 79 ¢ $ 99 $ 99 $ 99 2 Each1 Lb. -

Carbonated Soft Drink Demand: Are New Product Introduction Strategies a Viable Approach to Industry Longevity

LIBRARY Miningan State University This is to certify that the thesis entitled CARBONATED SOFT DRINK DEMAND: ARE NEW PRODUCT INTRODUCTION STRATEGIES A VIABLE APPROACH TO INDUSTRY LONGEVITY presented by Marcus A. Coleman has been accepted towards fulfillment of the requirements for the MS degree in Agriculture Economics Major Professor’s Signature Y/4/fl52 Date MSU is an Affinnative Action/Equal Opportunity Employer PLACE IN RETURN BOX to remove this checkout from your record. TO AVOID FINES return on or before date due. MAY BE RECALLED with earlier due date if requested. DATE DUE DATE DUE DATE DUE 5/08 K:IProj/Acc&PreleIRC/DatoDm.indd CARBONATED SOFT DRINK DEMAND: ARE NEW PRODUCT INTRODUCTION STRATEGIES A VIABLE APPROACH TO INDUSTRY LONGEVITY By Marcus A. Coleman A THESIS Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Agriculture Economics 2009 ABSTRACT CARBONATED SOFT DRINK DEMAND: ARE NEW PRODUCT INTRODUCTION STRATEGIES A VIABLE APPROACH TO INDUSTRY LONGEVITY By: Marcus A. Coleman In an industry dominated by multiple product introductions differentiated at the attribute level, carbonated soft drinks (CSDS) experience demand pressure from all aspects of the beverage industry that go beyond CSDS. The main objective of this paper is to analyze demand for new and sector leading CSDS, which are characterized by multiple product consumer purchasing behavior, firm promotional activity and differentiation at the attribute level. Given the many unique strategies for innovation in CSD new product introductions (NPIS), it is imperative to find out just how effective firm innovation strategies are in using NPIS to stimulate and revitalize demand for CSDS.